By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Mounted by the Seattle Art Museum (SAM), “The Treasures of Tutankhamun” attracted 1.3 million visitors to the Seattle Center in the summer of 1978, almost all of whom (along with almost everyone else on earth) ignored a story playing out on the same grounds at the same time, an amusing sporting experiment called World Team Tennis.

On a good night, 3,000 curiosity seekers would filter into the Seattle Coliseum to watch the local franchise, the Cascades, trade lobs and volleys with the Phoenix Racquets, Los Angeles Strings and New York Apples, among others. But on most nights, only 1,000 or so rattled around the smaller Mercer Arena, site of most of the teams engagements.

Although WTT, largely the creation of San Francisco entrepreneur Larry King, then a partner in domestics with his tennis diva wife, the former Billie Jean Moffit, had been in operation for four seasons, it remained a bane to the sports purists, a rumor to the populace, but a boon to the players.

Most pros loved WTT. It amounted to easy guaranteed money for a 13-week season (the average player made $3,900 per week at a time when the average pro basketball player made $3,300), a chance to play on a team and represent a city, and a role reversal from their usual routine of trotting the globe as athletic mercenaries.

WTT had distanced itself from traditional tournament tennis in a variety of ways. Instead of five-set (men) and three-set (women) formats, WTT matches consisted of one set each of mens and womens singles, mens and womens doubles, and mixed doubles, with points awarded on the basis of games won.

Matches featured halftimes, overtimes and another WTT innovation, the super tiebreaker. WTT, which played its matches on multi-colored courts with a fast “Sporteze” surface, also permitted on-court coaching and substitutions.

WTT encouraged fans (what there were of them) to yak, make noise, cheer, boo, heckle if they pleased, and even leave their seats during play if they wanted to make a concessions purchase — unpardonable offenses in traditional tennis.

In addition, fans could check league standings and chart playoff races, examine a variety of statistics, including mens and womens singles and doubles leaders, and even total offense leaders.

The first professional sports league in which men and women had equal roles, WTT never blanched at something new, one reason why the Soviet Unions national team became the first foreign entry to play in an American sports league (to the disgust of many).

Most of the great women players of the era Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Billie Jean King, Virginia Wade — embraced WTT, but many of the top-ranked men, notably Jimmy Connors and Arthur Ashe, did not (they could earn more in tournament prize money than they would have ever made in WTT).

Despite their absence, WTT drew heavy hitters into the ownership ranks. Jerry Buss, eventually the owner of the NBAs Los Angeles Lakers and NHLs Los Angeles Kings, thought so much of WTT and its prospects that he owned three franchises. Robert Kraft, later owner of the NFLs New England Patriots and MLSs New England Revolution, owned the Boston Lobsters.

Seattle came late to the WTT party due to another franchises misfortune. A charter member of WTT, the Hawaii Leis, who played in the 7,500-seat Honolulu International Center, could not outdraw the average luau even while employing the flamboyant Romanian Ilie Nastase (1972 U.S., 1973 French Open champion) and Australian grand dame Margaret Court, owner of 24 Grand Slam titles.

By July of 1976, Leis franchise owner Don Kelleher, who ran a lumber business based in San Rafael, CA., determined it was time to abandon the islands. Kelleher cast his eye toward Portland and Seattle, in large part because they were the only major West Coast cities without WTT franchises.

Kelleher arranged for the Leis to play a series of late-season home matches in Portland and Seattle to test the viability of the markets. One such match, featuring Nastase, Court and the Leis pitted against Everts Phoenix Racquets, attracted 8,500 fans to the Seattle Coliseum. The Portland match didnt draw as well, but Kelleher was apparently satisfied with his market research. He awarded each city half a franchise.

Asked why he selected both cities, which would necessitate two offices, two staffs, two playing facilities and different tax laws in two states (to say nothing of the fact that Kelleher would operate the franchise from San Rafael), Kelleher said, I just didnt want to make anybody mad.

Kelleher wanted Nastase as his coach and principal singles player, despite Nastases $140,000 salary. But Nastase refused to relocate to the Northwest, preferring instead to play Grand Prix events in France and Italy in the summer months (he eventually signed with the Los Angeles Strings). Kelleher also wanted Court as his top womens singles and doubles player. But Court was pregnant. Kellehers No. 2 choice, Evonne Goolagong, also was pregnant.

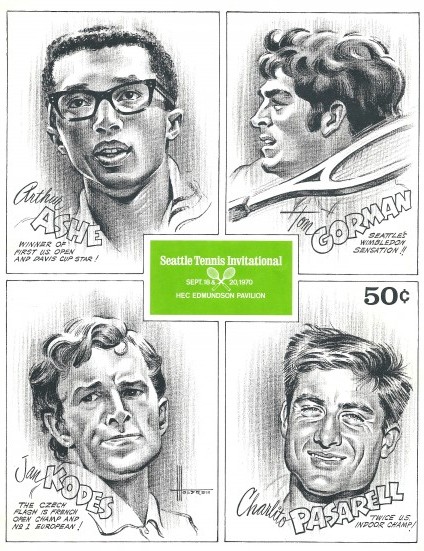

Kelleher made overtures to Tom Gorman, then ranked 12th among U.S. singles players (he had been ranked as high as No. 8 in the world in 1973). Famous in Northwest tennis circles (won three state singles titles while at Seattle Prep and made All-America twice while representing Seattle University), Gorman reached the semifinals of three majors: Wimbledon in 1971, the U.S. Open in 1972 and the French Open in 1973. He was on the U.S. Davis Cup team from 1970-75, and had victories over some of the worlds best players, including Nastase, Ashe, Connors, Jan Kodes and Roscoe Tanner.

Gorman didnt win a lot of tournaments (seven singles titles and 10 doubles titles in 12 years), but he won a few, and made headlines in 1971 by defeating Rod Laver, the worlds top-ranked player, twice in a two-week span (once on Center Court at Wimbledon).

Gorman initially expressed reluctance to join WTT, even if it meant playing in his hometown, but came around when Kelleher offered him a three-year deal that included a first-year salary of $60,000, not bad for a 13-week gig.

All my life Ive had this fantasy about representing Seattle in a team sport, Gorman said after his hiring. This is going to be a lot of fun because the people on the team are a lot of fun.”

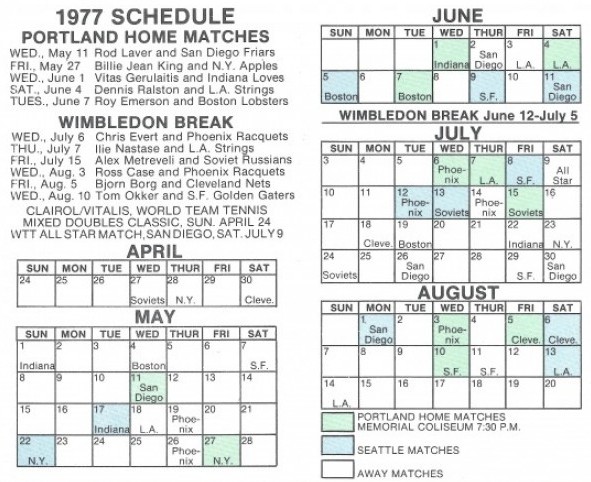

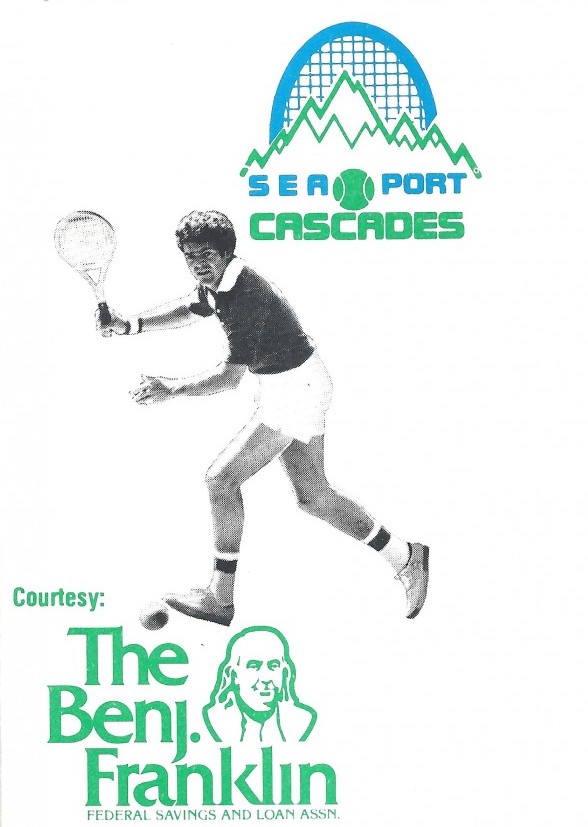

The newly christened Sea-Port Cascades came together quickly. Kelleher hired Marty Loughman as the teams general manager, brought aboard publicity director George Hill, salesperson Dianne Shorett, secretary/bookkeeper Molly Cheshier, and set ticket prices at $64.50 for courtside, $40 for loge (season), and $6.50, $4.00 and $1.50 (single match).

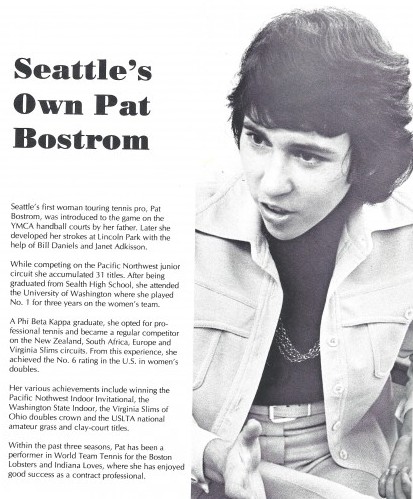

By the time Gorman joined on March 6, Loughman had signed 22-year-old doubles specialist JoAnne Russell of Naples, FL., as a free agent, picked up Betty Stove of The Netherlands in the WTT draft to occupy the womens singles role, and filled out his roster with Erik Van Dillen (doubles), former UW star Patricia Bostrom (1974 Boston Lobsters, 1975-76 Indiana Loves) and Northwest club professional Steve Docherty.

Loughman didnt have a roster studded with gate attractions. Worse, Kelleher allocated no money for advertising his teams matches. But the Cascades had at least two good ideas: They planned to set up youth leagues in Seattle based on the WTT format, and conduct a lot of tennis clinics in order to promote the franchise.

And what the Cascades roster lacked in star power, it made up for in personality. In particular, Gormans gregariousness made him one of the most likable professional athletes any fan, or member of the media, could ever hope to meet. Russell always sported a smile and had a flair for pranks, most involving ice cream and shaving cream. Stove had a bit of iciness about her, but Bostrom, who had aced her way through the University of Washington both in the classroom and on the tennis court, told wonderful stories about life on the tour.

Kelleher required 4,500-5,000 fans per match in order to justify his investment in the Sea-Port Cascades, and figured, incorrectly as it turned out, that all he had to do was open the Coliseum/Arena doors. Kelleher banked that names such as Evert, Navratilova (Boston Lobsters), King (New York Apples), Bjorn Borg (Cleveland-Pittsburgh Nets) and Laver (San Diego Friars) would sell tickets for him.

This is where Kelleher could have used more market research.

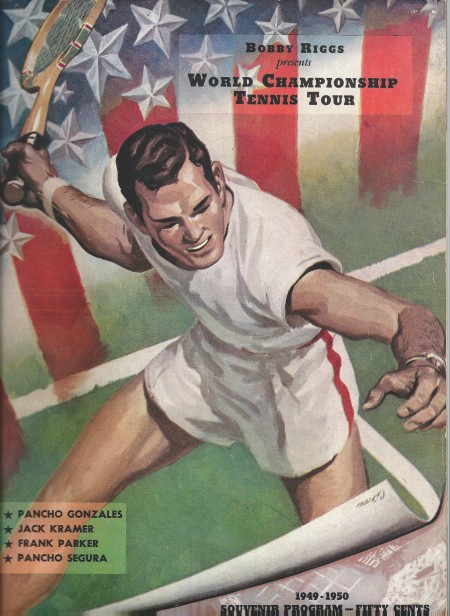

Professional tennis tournaments and exhibitions had been coming to Seattle since 1950 (the professional “Open Era” of tennis did not commence until 1968). On Feb. 1-2 that year, and despite considerable newspaper hype, only 5,000 spectators turned out for a two-day tournament — Bobby Riggs’ World Championship Tour of Tennis — featuring four of the top men in the United States: Jack Kramer, Pancho Gonzalez, Pancho Segura and Frank Parker. In the final (Feb. 2) at Civic Auditorium, Kramer defeated Gonzalez in a corker — 27-29, 6-4, 6-3 — witnessed by just 3,000.

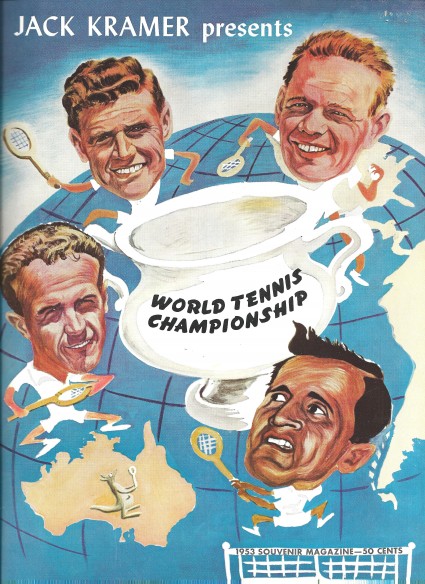

Three years later, on May 19, 1953, Kramer, Segura, Frank Sedgman and Ken McGregor drew just 1,820 to Civic Auditorium for Kramer’s World Tennis Championship tour, won by Kramer over Sedgman, 6-4, 6-8, 12-10. In 1970, the Seattle Invitational at Hec Edmundson Pavilion had a two-day attendance of 11,500, including 6,100 for the championship match between Ashe and Gorman.

The same year (1976) that Kelleher test-marketed the Cascades in Portland and Seattle, The Association of Tennis Professionals pulled the plug on an indoor West Coast circuit that, between 1972-76, included Seattle, San Francisco, Portland and San Diego. The tournaments (known as the Rainier Classic in Seattle) failed to generate much enthusiasm in any of the cities (the 1976 tournament final in Seattle drew just 2,534).

Further, the Virginia Slims of Seattle, a one-week indoor tournament held the previous January, drew all the big names from the womens circuit, but its promoters also took a financial bath.

At Kellehers insistence, and following a one-week training camp in Houston, the Cascades began their 44-match regular season (22 home matches split between Seattle and Portland) with seven matches on the road, including four in five nights in Knoxville (they played the Soviet National Team, based in Philadelphia), Pittsburgh, New York and Indianapolis. Kelleher reasoned that the Cascades would sweep all seven matches, return as conquering heroes and draw throngs for their home opener.

The Cascades didnt win all seven, but went 5-2 with Gorman scoring an impressive 6-2 win over Borg, two months away from winning the second of his five Wimbledons, in Pittsburgh.

To Kellehers dismay, Seattles 5-2 record failed to empty “The Treasures of Tutankhamun” exhibits. The Cascades drew 2,675 for their home opener on May 17, a 28-22 overtime victory over the Indiana Loves, which included Robert Julien, the singing bartender from Jake OShaughnesseys, crooning the National Anthem. Gorman won the mens singles, beating the non-descript Allan Stone 7-5.

The Cascades played entertaining (if not always successful), tennis, only to be greeted by yawning apathy. On May 22, the Cascades beat Billie Jean King and New York Apples 23-20 in front of 3,985 fans, and that was a big crowd. A match in Portland on June 7 against the Boston Lobsters drew fewer than 1,000. A match in Seattle on June 9 against the Golden Gaters didnt do much better, just 1,213.

In their last match before the three-week Wimbledon break, on June 11, the Cascades edged the San Diego Friars 23-22 in Seattle as Gorman topped Laver 6-4 in front of 2,013 fans. A day after the match, with no warning, Kelleher fired the eminently capable public relations director George Hill.

We looked around at all the empty seats and felt we needed to be more sales oriented, Kelleher said, referring to the clubs average attendance of 2,471, but making no mention of the fact the Cascades had dropped nine of 11 matches.

In response to Hills ouster, both secretary/bookkeeper Cheshier and salesperson Shorett quit. On her way out the door, Shortett filed suit in King County Superior Court against Kelleher, seeking $3,360.03 in unpaid salary and commissions.

Kelleher, who had yet to advertise Cascades matches, figured the franchise would receive a second-half attendance spike from an unexpected source: Wimbledon. Stove had the tournament of her career, reaching the finals in singles, doubles and mixed doubles. Russell, without a partner when she arrived at the All-England Club, scrounged around until she found Helen Gourlay, and then won the doubles, beating Cascades teammate Stove and Navratilova. Bostrom, meanwhile, teamed with Karen Sussman for an early-round doubles triumph over Billie Jean King and Virginia Wade, the tournament favorites.

The interest in the Cascades is definitely building and Im very pleased with the direction I see us taking in the second half, Kelleher said, without a shred of evidence to back up his opinion.

Kelleher, in fact, received awful evidence to the contrary when only 1,842 showed up to see the Cascades fall to the Golden Gaters 28-22 to start the second half, but was briefly buoyed by the 7,208 that came to watch Evert and the Racquets on July 12.

The high moment for the franchise occurred on Aug. 8 when Borg helped draw a season-high 7,642 and sent the customers home happy by losing to Gorman 7-5.

Despite an 18-26 regular-season record, the Cascades qualified for the WTT playoffs opposite Phoenix. In hindsight, it might have been better had they missed the postseason.

Kelleher refused to spend any money advertising the Cascades one home playoff match, scheduled for Lewis and Clark College in Portland, reasoning that Evert would attract a mob by her mere presence. But the utter lack advance ticket sales so alarmed Loughman that he resorted to a tactic that became the signature event in Cascades history.

I drove to Portland and took a loudspeaker system and put it on the top of my car and went around downtown Portland advertising the fact that Chris Evert and the Phoenix Racquets were actually going to be in town that night, Loughman said. I felt like a fool that this had to be done, but I wanted to get some people in the arena.

Despite Loughmans public honking, fewer than 700 showed, and Evert reacted as if she had been stood up by her date to the prom.

I havent played before a crowd like this, in a high school gym like this, since I was playing juniors, Evert stammered.

Embarrassed by that debacle, and for a litany of other reasons, Loughman resigned as general manager on Sept. 7, saying, Its Don Kellehers team and his money and hes entitled to run the club and spend his money any way he wants. But for me to be involved it had to be more professional.

Perhaps (and perhaps not) jarred by Loughman bailing on him, Kelleher announced four days later that the franchise would abandon Portland and play all of its 1978 matches in Seattle. While both cities had averaged about 3,100 fans per match, the 700 for the Portland playoff disaster proved decisive in bringing the team exclusively to Seattle.

Most WTT franchises struggled at the gate. No matter how entertaining the tennis, or how accommodating the players, the public simply refused to buy the show. In fact, in Bostons early WTT days, the owner of the Lobsters grew so desperate to draw fans that he employed college students to bring three bus loads of patients to a match from a local mental institution.

Several weeks after Loughman quit, John DeVries announced that he had been named executive director of the Cascades, and that he planned to make them a great franchise. But three months after signing on, DeVries was ousted in a front-office coup, which followed the resignations of a dozen sales people.

Joining the franchise was one of the worst mistakes of my life, DeVries said. They are still not a first-class operation. What they need are new owners. They are still looking for the Seattle business community to support them. They are Jesse James trying to get into everybodys pocket.

In an attempt to minimize his mounting losses, Kelleher took on four local investors, headed by radio man Howard Leendersten. This group made one positive move, hiring Pat Dawson as operations director. Dawson had strong local ties and had spent more than four years working in the Longacres publicity department. Dawson had the connections to give the Cascades more credibility than they had ever enjoyed (Dawson spent the 1978 season in mortal fear that the Cascades would draw fewer customers than the International Volleyball Association’s co-ed Seattle Smashers).

For the 1978 season, the Cascades imported a number of new faces. Sherwood Stewart, a Texas doubles specialist, replaced Van Dillen, Marita Redondo came aboard, replacing Russell, and Brigette Cuypers and Chris Kachel also signed on. The Cascades featured a marginally better team than the 1977 club, but nothing changed at the gate except that attendance continued to wane.

The Cascades and San Diego (Laver) attracted just 1,536 on July 15. Two nights later, the Cascades and New Orleans Nets drew 1,047. Navratilovas appearance on July 20 with the Boston Lobsters interested only 2,145.

Billie Jean Kings Apples drew even less 2,039 two weeks later, perhaps owing to the fact that the Cascades did not run one ad promoting the match, which provided one of the seasons kookiest moments.

After Gorman defeated Vitas Gerulaitis 6-4 in the fourth set of the night to give Seattle a 21-17 lead heading into mixed doubles, King and Ray Ruffels captured that set 6-2. That tied the match at 23-23, setting up the super tiebreaker.

Stove and Stewart took a 5-1 lead in the best-of-13 point extra session behind Stoves two slicing serves and Sherwoods hard volleys. Then, as King and Ruffels passed in front of the scorers table as the teams traded courts, Bruce Below, the Cascades scoreboard operator, blurted, You guys are in trouble now.

At that moment, Billie Jeans blood began to behave like the mud pots in Yellowstone Park. King and Ruffels stared angrily at Below and then King screamed, Do you work for the team? When Below replied that he did, King said, Well, then shut up. If youre working for them you shouldnt be saying anything.

The Cascades won two of the next three games for the set and match, immediately after which Ruffels raced toward Below, grabbed him by the neck and shook him like a rag doll before he could be restrained by the umpire, Brian Howell, and his linesman. King then became Kong, verbally blistering Howell, then grabbing and shoving him. Then she slammed her racquet on the table.

The following night, the Cascades hosted the Indiana Loves at Mercer Arena. Only 846 fans showed up to witness perhaps the greatest example ever of WTT multi-tasking. Below, the previous nights scoreboard operator, drew duty as Mr. Peanut. At least in Mr. Peanut garb, his neck was safe.

Although the Cascades posted a 20-24 record and upset the division-winning San Diego Friars in the first round of the playoffs, the team averaged just 1,695 per match, down from 3,100 in 1977.

In late October, after the Cascades made an early playoff exit, Kelleher and his minority partners announced that the club would not return to Seattle and might be sold to Houston interests. But after Kelleher failed to come up with a letter of credit ensuring that operating costs would be covered in 1979, that became moot when the Cascades and the rest of World Team Tennis suddenly folded to little lament. And then everybody moved on as if nothing had ever happened.

Gorman returned to tournament tennis. After retiring as a player, he coached U.S. Federation Cup and Wightman Cup teams in 1984-85. In both 1988 and 1992, he coached the U.S. Mens Olympic tennis teams. From 1986-93, Gorman served as captain the U.S. Davis Cup team (his squad won titles in 1990 and 1992 and was runner-up in 1991). Gorman entered the NCAA Tennis Hall of Fame in 1995 and the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 1997.

Stove won one singles title and 75 doubles titles in her career, including 10 in Grand Slam events. She also finished as runner-up in 17 Grand Slam doubles events.

Russell, ranked No. 1 in the world in womens doubles in 1978 (along with Rosie Casals), joined the Apples in 1978 and played on the WTA Tour until 1988, after which she went into broadcasting and ultimately became an assistant coach at the University of Illinois.

Stewart went on to win 51 doubles titles, one of his biggest at the 1984 Australian Open. After his career ended, Stewart coached Zina Garrison (defeated Evert in the quarterfinals of the 1989 U.S. Open in what was the final Grand Slam singles match of Evert’s career).

Bostrom, the former UW star, achieved rankings as high as fifth in world doubles and 30th in womens singles. She received her law degree from Southern Methodist University in 1983 and became a successful Seattle attorney. In 2000-01, she served as president of the UW Alumni Association. She entered the Husky Hall of Fame in 1987 and the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 2006.

World Team Tennis remained dark until 1981, when new operators resurrected it, branding it TeamTennis. In 1992, the name was changed back to World Team Tennis and the league continues today, minus, of course, a franchise in Seattle, which botched its shot more than 30 years ago.

Instead of running the team like a business, he (Kelleher) ran it like a lemonade stand, said George Hill, who went on to a long career with ABC Sports. I think he believed you could open the doors and people will walk in.

Said Pat Dawson (to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer): At Longacres I learned how to do things the right way. I spent seven and a half months with the Cascades learning the flip side. The franchise went down 28-0 in the first quarter and then it started to rain. You become aware of something through a series of impressions and reinforcements. The public never really became aware of us. Its sad there wasnt a team (after 1978). But its sadder nobody ever knew there was one.

Check out David Eskenazis Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

17 Comments

Amazing the details you guys can dig up about events such as these which, quite frankly, most people, at least at first glance, probably do not even remember existed. Those were glorious times in Seattle, though. Seattle on the cusp of, and really arguably in the middle of for the next five years or so, its Apex.

Amazing the details you guys can dig up about events such as these which, quite frankly, most people, at least at first glance, probably do not even remember existed. Those were glorious times in Seattle, though. Seattle on the cusp of, and really arguably in the middle of for the next five years or so, its Apex.

Fantastic article and wonderful photos. Here is another post on the Hawaii Leis/Sea-Port Cascades franchise owned by Don Keller on the Fun While It Lasted blog. David’s post puts mine to shame, but I’ll settle for second place on this one.

http://funwhileitlasted.net/2011/06/21/30-hawaii-leis-sea-port-cascades-seattle-cascades/

Thanks for reading, and for the nice comments. All hail Steve Rudman who does all of the research and wonderful authoring of the Waybacks. We are happy to present these slices of Seattle sports history….please come visit again!

Fantastic article and wonderful photos. Here is another post on the Hawaii Leis/Sea-Port Cascades franchise owned by Don Keller on the Fun While It Lasted blog. David’s post puts mine to shame, but I’ll settle for second place on this one.

http://funwhileitlasted.net/2011/06/21/30-hawaii-leis-sea-port-cascades-seattle-cascades/

Thanks for reading, and for the nice comments. All hail Steve Rudman who does all of the research and wonderful authoring of the Waybacks. We are happy to present these slices of Seattle sports history….please come visit again!

Great, great piece! I went to two matches in Portland. The first featured the Phoenix Racquets with Chris Evert. When we got to the ticket window a hand-written sign said “Chris Evert will not play tonight.” The second featured a Rhodesian player who may or may not have been Andrew Pattison. He was about to serve and my best friend yelled out “Fault!” Pattison stopped, the crowd booed and yelled at my friend who said something like “I thought this was a new type of tennis. I thought we could yell.” Brilliant.

Great, great piece! I went to two matches in Portland. The first featured the Phoenix Racquets with Chris Evert. When we got to the ticket window a hand-written sign said “Chris Evert will not play tonight.” The second featured a Rhodesian player who may or may not have been Andrew Pattison. He was about to serve and my best friend yelled out “Fault!” Pattison stopped, the crowd booed and yelled at my friend who said something like “I thought this was a new type of tennis. I thought we could yell.” Brilliant.

Wow.

The Yankees are the type of club Ichiro should have been on since day one. One can only wonder what the last decade for the Mariners could have been–and of course when you are talking about the Mariners one is talking about a HUGE if– without a fairly weird, non-English speaking–to a greater or lesser extent, and we also are not talking Spanish–loner-type who still was expected to be the face of the franchise as well as the player the other players inherently were going to be inclined to glance at when looking for leadership The only leadership Ichiro apparently could bring himself to provide was the jackass routine he would put on every year for his all-star teammates. But, in the end, Seattle got EXACTLY what it deserved, as Seattle is SOLELY responsible for the fact the Mariners had to go halfway around the world to find someone willing to own the team and keep it in Seattle. “Baseball Club of Seattle.” That term was, and still is, one of the biggest jokes in baseball.

“…the Mariners were trying to get him to sign an extension. Club president Chuck Armstrong reported Monday the most recent effort was in June.”

Art, I’m not sure which aspect of this quote is more concerning. The fact that the Ms were trying to sign Ichiro to an extension, or the fact that Armstrong admitted as much.

No additional evidence needed to demonstrate the M’s senior management are clueless.

Clueless.

Ichiro did not fit with this team and wasn’t welcome. He said as much. He probably would have rather have ended his career here but management never built on what the 2001 team set. When players like Edgar, Boone, Buhner, Wilson and Olerud left they were replaced by Sexson, Aurilla, Spiezo, Figgins and Kotchman. Don’t even get me started on Adrian Beltre who found the fountain of youth when he left. And I imagine Ichiro got frustrated when he sees how well Raul Ibanez, Adam Jones, Shin Soo Choo and Asdrubal Cabera have played for their respective teams. Think of the protection they could give him in the lineup today.

It could be argued that Ichiro is getting old, but I look at Rickey Henderson’s career who was still productive in his later years. The difference is he played for teams that gave him solid protection in the lineup as well as pitching staffs that kept their teams in contention. Hmm…didn’t he play for the M’s?

I hope he does well for the rest of the season. He deserves a ring. Wish the M’s got more for him but I guess they more wanted to trade him moreso than anything else.

yep. this is a win-win-win scenario. Good luck and godspeed, Mr. Suzuki.

Nice piece, Art. Both teams come out ahead in this one: The Yankees get a veteran OF who can give them some hits, stolen bases and decent defense, while the Mariners clear $17 million off the payroll while their young OFs get more ABs to prove whether or not they belong in MLB next year. As jimc says, it’s a win-win.

Good luck to Ichiro in NY. I’ve never rooted for the Yankees (I don’t hate ’em…I just don’t LIKE ’em), but I won’t root against them this year if it means Ichiro wins a pennant and plays in a World Series. This is a guy who absolutely should go to Cooperstown and his plaque will certainly depict him wearing an M’s cap. Can anyone say they’re sure of the same with Griffey, Johnson or A-Rod?

These gun-for hire days of free-agency, contract re-negotiations, hold-outs, unbelievable salaries, escape clauses, endorsement deals, etc., I’ve become cynical (or maybe just pragmatic) enough to accept that player loyalty in pro sports is mostly just another commodity to be bought and sold. But this event is a stark reminder of the flip-side of that coin. What happens to a superstar when surrounded by mediocrity year after year, especially when his career arch started at such a high point?

I sometimes wondered, had Ichiro not worn that elbow pad on his right arm and been hit by a hard slider, if wires and circuits would then appear beneath the broken skin instead of flesh and blood. Yet, as methodically professional as both his game and demeanor have always been, not even he was immune to the malaise that has befallen this franchise. I’d go so far to say it was sucking what’s left of his life out of him at an accelerated rate.

I would bet that Ichiro’s performance will improve substantially now…. and not merely the temporary invigorating effect of a trade, and not simply because he is now an ex-Mariner (although that fact alone should automatically add about 30 points to his batting average), but because he is now surrounded by better players. And every good athlete innately knows, you don’t just compete against your opponents.

Now, when do I get my Ichiro Bobblehead with a Yankeee cap?

I have to say, I really hope so. I want Ichiro in this league for another 3-4 years, and collecting 3000 at least. I think he might eventually land with the A’s, though (just a weird feeling), so the M’s will see plenty of him yet.

SPNW likes to refer to the Mariners career history as “mediocre.” The Mariners career record sits around .450, clearly to the low side, especially given the amount of games at issue, of “mediocre,” and stating that it is to the “low side” of mediocre is clearly, at least, arguably too generous. Much closer to .400 and it would not even be a debate.