By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Camptonville, CA., 36 miles from Marysville, off Highway 49 between Downieville and Nevada City, and about 70 clicks northeast of Sacramento, sits on a ridge between the North Fork and Middle Fork of the Yuba River in the shadow of the Sierras. Camptonville bills itself as “The Little Town That Could,” apparently because it has survived winters with so little rain that wells went dry, and others with so much rain and snow that people had to be rescued from their homes.

Named after Robert Campton, a long-ago blacksmith, Camptonville had 1,500 residents and more than 50 saloons and brothels (plus a bowling alley) at the height of the California Gold Rush (1848-51). Today, due to downturns in the timber and mining industries, it has a population of just 158, according to the 2010 U.S. Census.

Camptonvilles eldest citizen — he actually lives in the woods on the outskirts of town — is pushing 97 now and holds the distinction of being the fourth oldest-living former professional football player, and also the oldest-living former University of Washington head basketball coach, giving him a two-year edge on 95-year-old Marv Harshman, who tutored Husky hoopsters from 1970 through 1985.

Laudable as they are, good genes are the least interesting aspect of Camptonvilles reigning relic. Among many amazements, he:

- Is named after a U.S. president and played college football against another one.

- Served as a Senate page in the Ohio statehouse with the star of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games.

- Played three sports in college and made All-America in two and All-Big Ten in all three.

- Twice played in games documented by Grantland Rice, the great dispenser of on-the-spot immortality who made a quartet of Notre Dame football players The Four Horsemen, branded Ty Cobb The Georgia Peach, and turned Red Grange of Illinois into the Galloping Ghost.

- Is one of two quarterbacks in either the 20th or 21st centuries to quarterback three consecutive victories over Michigan, and the only one to orchestrate three straight shutouts over the Wolverines.

- Played in what is widely regarded as college football’s first “Game of the Century,” the 1935 battle between Ohio State and Notre Dame.

- Played in the 1937 Chicago Tribune College All-Star football game with Sammy Baugh, the Peyton Manning/Aaron Rogers of the 1930s/1940s.

- Was offered contracts by the New York (football) Giants and St. Louis (baseball) Cardinals, but declined both.

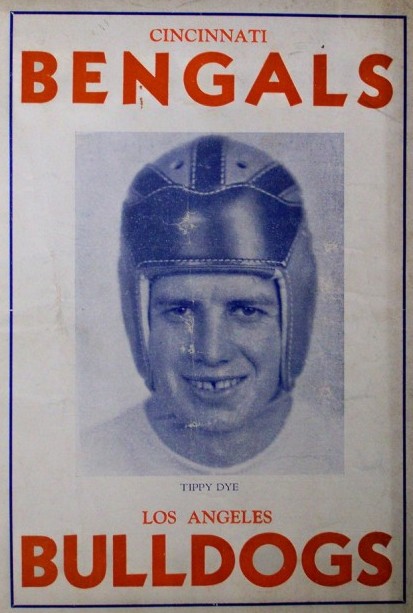

- Played for the original Cincinnati Bengals (1937) of the second American Football League (1937-38).

Dye, a quarterback, appeared on the cover of a 1937 game program for a matchup between the American Football League's Cincinnati Bengals and Los Angeles Bulldogs. Dye played for the Bengals. / Image by Cincinnati Sports History - Was coached by one Pro Football Hall of Famer and served as an assistant coach under another.

- Coached a Pro Football Hall of Famer and a Basketball Hall of Famer, teaching one the T-formation and the other the hook shot.

- Became the first to coach two different NCAA basketball schools to top-20 Associated Press finishes in back-to-back years.

- Turned down a job that made John Wooden famous.

- Coached the University of Washington basketball team to its only Final Four appearance.

- Made the key hire that turned Nebraska into a college football powerhouse.

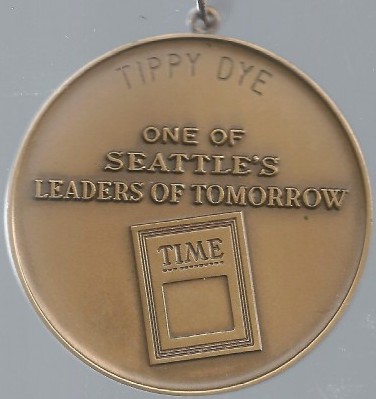

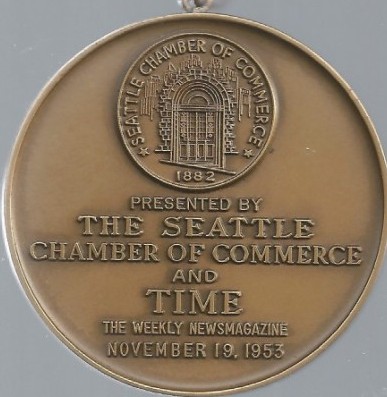

We got to thinking about the man behind this remarkable history, Tippy Dye, after learning that one of Dyes former protégés, 80-year-old Bob Houbregs, would receive the Legends Award at the 77th Sports Star of the Year awards banquet Jan. 25 at Benaroya Hall.

It’s a well-deserved accolade for Houbregs, who had a legendary career as a basketball All-America at the University of Washington from 1951-53, under Dyes direction. Dye, by contrast, had legendary careers in three capacities, as an athlete, coach and administrator, first at Ohio State, then at Washington, and finally at Nebraska.

With William Henry Harrison Tippy Dye, born April 1, 1915, in Harrisonville, OH., a town named after William Henry Harrison, the ninth U.S. president, its hard to know where to start, so well start with why everyone calls him Tippy.

The original William Henry Harrison was one of the heroes of the War of 1812 and, preceding that, distinguished himself in the Battle of Tippecanoe against Tecumeshs American Indian confederation. When Harrison sought to become president in 1840, he selected John Tyler (10th U.S. president, 1841-45) as his running mate. Their campaign motto: Tippecanoe and Tyler too. Thus, Tippy.

Tippy Dye left Pomeroy, OH., where he grew up and attended high school, in 1933 to enter Ohio State University, opting to enroll there mostly because the girl he had been courting, Mary Russell, was headed there.

When Dye, who stood 5-foor-7 and weighed all of 135 pounds, turned out for football in his freshman year, the coaching staff slotted him on the seventh string, no position designated. But by the end of the season, Dye had become the yearling teams No. 1 quarterback.

Dye took command of the varsity in 1934 as a sophomore, working under head coach and trick-play specialist Francis Schmidt (College Football Hall of Fame inductee in 1971), and a graduate assistant named Sid Gillman, a former Buckeye end who would become a Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee in 1983 and a College Football Hall of Famer in 1989.

Before the 1934 Ohio State-Michigan game, the Columbus, OH., press asked Schmidt about his teams chances of beating the Wolverines. Schmidt famously replied, Those fellows put their pants on one leg at a time, the same as everyone else.

Had Dye not directed the Buckeyes to a 34-0 victory (two touchdowns), Schmidts quote, which up to then had been a quaint Texas regionalism, would not have generated the massive press attention that it did, nor evolved into the cliché it is (since that game, any Ohio State player who participates in a victory over Michigan is awarded a Gold Pants Charm, a gold lapel pin shaped like football pants.).

Dye not only beat Michigan in 1934, when the Wolverines featured center/linebacker Gerald Ford, who served as president from 1974-77, he did it again in 1935 (38-0, in a game in which Dye returned a punt 73 yards for a TD) and in 1936 (21-0), becoming the first quarterback in school history to orchestrate three consecutive shutouts over the Wolverines (the feat of three straight Ohio State wins over Michigan, all orchestrated by the same Buckeye quarterback, would not be duplicated until Troy Smith did it from 2004-06, the caveat being that none of Smith’s wins were shutouts).

One of the more memorable college football games in which Dye played was in 1935, when the Buckeyes lost the first “Game of the Century” 18-13 to Notre Dame in front of 81,018 at Ohio Stadium. Chronicled by famed sports writer Grantland Rice, Dye had the Buckeyes in front 13-0 heading into the fourth quarter, but the Irish rallied behind Bill Shakespeare to pull out the win.

The Buckeyes have featured few athletes who starred across the board as Dye did. In addition to the three football letters he won as a quarterback, defensive back, punter and punt returner (on Nov. 17, 1935, Dye returned a punt 50 yards for a touchdown, giving Ohio State a 6-0 win over Illinois), Dye played guard on Ohio States basketball team, lettering in 1935, 1936 and 1937.

During Dyes time, the Ohio State basketball team compiled a 38-21 record. Dye made first-team All-Big Ten in 1936 and 1937, when he was captain. Dye also lettered in baseball in 1935 and 1936.

Dye might have been considered Ohio States greatest athlete during his varsity years if Jesse Owens hadnt been enrolled at the school at the same time. Both Dye and Owens served as page boys in the state capitol in Columbus, a job given to scholarship athletes in those days.

“In Owens book, there is a picture of the two of us running up the steps of the statehouse, going to work,” Dye told the Los Angeles Times a number of years ago.

“I didn’t get to see him compete much, because I was in baseball and he was in track and we were always on different fields. But one time, I watched him in the Big Ten meet. He was in the 220 low hurdles and he hit the first hurdle. Must’ve flown 15-20 feet before he hit the ground. Then he got up and won the race.”

The football Giants and baseball Cardinals offered Dye contracts as he exited Ohio State, but neither offer piqued his interest.

“I didn’t want to play either sport, Dye said. I wanted to play basketball, but they didn’t have a pro sport yet.”

So after participating in the 1937 College All-Star Football Game against the Green Bay Packers at Soldier Field (collegians upset the Packers 6-0), playing in a backfield that included future pro legend, Sammy Baugh, Dye signed to play with the first incarnation of the Cincinnati Bengals, a member of the second American Football League, in 1937.

After his one-year stint with the Bengals, Dye entered the coaching ranks, first at Grandview Heights High School in Columbus (1939-41). Then he moved to Brown University as varsity basketball coach and assistant football coach.

On Aug. 12, 1942, Dye returned to Ohio State as a football assistant under Paul Brown (founded the Cleveland Browns and Cincinnati Bengals) and a basketball assistant under Harold Olsen, who spearheaded efforts in 1939 to create the NCAA Tournament.

When Dye entered the service during World War II, the Navy assigned him to its V-5 pre-flight school at Chapel Hill, NC., where, as one of the coaches of the North Carolina Naval Pre-Flight Cloudbusters, he had a chance to mentor a talented athlete who at Northwestern had been one of the few to make All-America in both basketball and football.

“Taught Otto Graham a lot about the T-formation, like Francis Schmidt had taught us at Ohio State,” Dye said of his time with Graham in the military.

Ohio State hired Dye as its head basketball coach in 1947, a position he held through the 1950 season, when the Buckeyes won the Big Ten title (22-4 record) and reached the Elite Eight of the NCAA Tournament.

Despite his success at Ohio State, Dye decided to pull stakes. He wanted to become an athletic director and figured he needed to know as many people in as many places as he could in order to make that happen. In 1948, he mulled taking the UCLA job, but declined it when offered.

Im glad I did, Dye told an interviewer. John Wooden took that job after I turned it down.

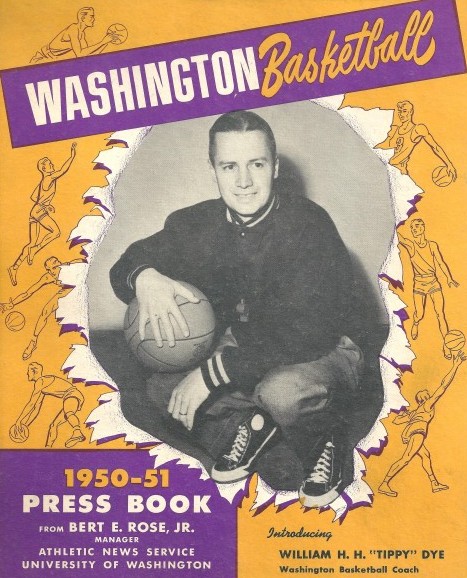

Dye became the UW basketball coach on June 2, 1950, when athletic director Harvey Cassill, then trying to build the UW into a national athletic power, offered him $12,500 per year (Ohio States best counter offer was $7,500). Dye walked into terrific situation.

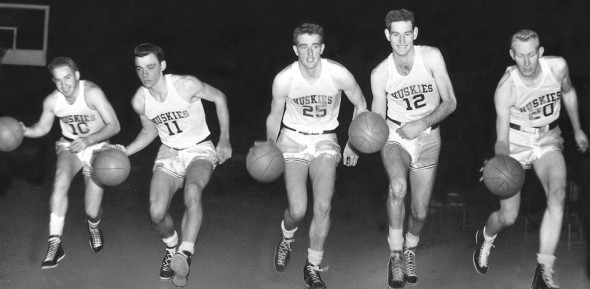

His upperclassmen included All-Coast forward Frank Guisness and Doug McClary and a marvelous sophomore crop featured Joe Cipriano, Mike McCutcheon and Houbregs. With this group, the Huskies went 24-6 and reached the NCAA Tournament for the first time since 1948 (the Huskies lost those six games by an average of just 4.5 points).

UW finished the season ranked No. 15 by the Associated Press (Washington’s first-ever top-20 finish), making Dye the first coach in college basketball history to produce a top-20 team at different schools in back-to-back years (his 1950 Ohio State team finished No. 2 in the rankings).

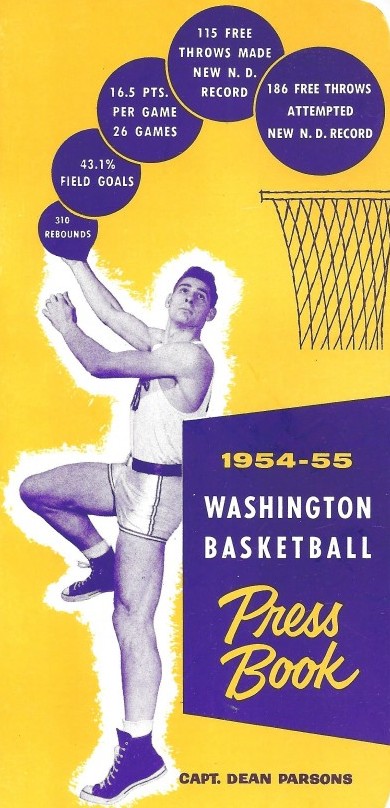

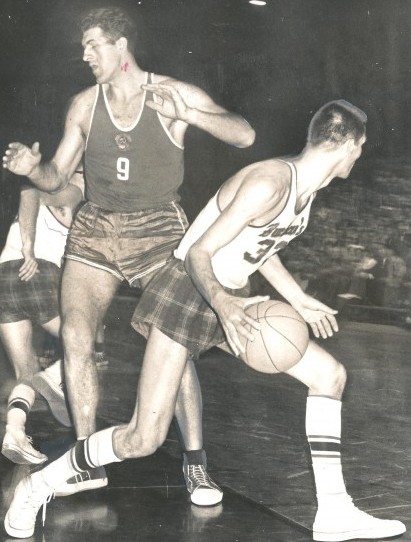

Between 1951 and 1959, Washington went 156-91, and Dyes first three teams 1951-53 were clearly his best. The 1952 Huskies went 25-6, finished at No. 6 in the national polls, and may have been Dyes best, although the Huskies failed to prove it by losing to UCLA in the Pacific Coast Conference playoffs and failing to reach the NCAA Tournament.

Led by Houbregs, who had mastered the famous hook shot Dye taught him, the Huskies went 28-3 in 1953 and reached the Final Four in Kansas City ranked No. 4 nationally and favored to win it all. But the Huskies fell to Kansas in the national semifinals when Houbregs fouled out early in the second half on several questionable officiating calls (see Wayback Machine: Bob Houbregs & The 53 Final Four).

Washingtons success during Dyes first three seasons had everything to do with Houbregs and the hook shot Dye taught him. With it, Houbregs became the leading scorer in UW history, a consensus All-American, the 1953 NCAA Player of the Year, a five-year professional and, in 1987, a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame.

“I built those teams around Houbregs, naturally, just getting the ball to him,” Dye said. “It was very simple. There was nothing to it.

Dye last visited Seattle in 2008, and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer listened in on a conversation Dye had with Houbregs.

I got to thinking what kind of player I would have been if you hadnt shown me the hook shot, Houbregs told Dye. You made my career.

We could argue a long time on that, Dye replied. You could shoot so well. I dont know if you would have gotten as many shots without the hook, though.

Later, Dye added, I don’t know that I helped Houbregs a great deal. I taught him the hook shot. He was a good shooter prior to that. No matter what kind of shot he had, he was going to be a good scorer and a good shooter. This just happened to be something I liked to do with my centers, having a good hook shot. It fit into our offense. In fact, it was our offense and it worked well for us.”

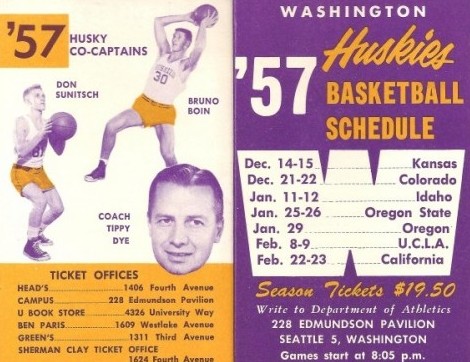

Aside from the Final Four appearance in 1953, two significant developments occurred in Washington athletics during Dyes tenure. First, the Husky basketball team finally accepted African American players. Second, UW went on NCAA probation in all sports as a result of a slush-fund scandal in the football program.

The Huskies became integrated when sophomore Dick Crews joined the team for the 1955-56 season. However, it didn’t happen without intense negotiating, with Garfield coach Bob Tate and others encouraging Dye to add Crews, who led the Bulldogs to the 1954 Class A state championship game, to his roster.

Crews lettered in 1956, 1957 and 1958, when he started at guard on just the second losing team Dye coached at Washington.

Dye fielded one of the nation’s tallest teams in 1958-59, featuring 6-9 Bruno Boin and 6-7 Doug Smart, but after the Huskies lost three of their first four conference games, some rankled fans hung Dye in effigy from a utility pole in the downtown business district. A crudely lettered sign pinned to the dummy said, Tippy, You Are Through.

Although the Huskies finished 18-8, the sign pretty much had it right, but not for the reason that Dyes executioners had intended. When Washington went on probation, the school ousted athletic director Cassill and imported 33-year-old George Briggs from the University of California to clean up the mess. Briggs finished his work in three years, resigning in 1959.

Dye wanted to become UW athletic director, but didnt get it, losing out to football coach Jim Owens.

“I wanted that job,” Dye said. “Unfortunately, I didn’t make it. I knew I could do it.”

Dye figured the time was ripe to move on. So after compiling a 156-91 record in nine seasons, Dye resigned in order to become athletic director at Wichita State for a salary of $13,000 per year, about what he made at UW.

Dye stayed at Wichita State for two years, then accepted one of the biggest challenges of his career turning around a moribund University of Nebraska football program.

Given Nebraskas football success over the past half century, its hard to believe today that the program ever floundered. But prior to hiring Dye, the Nebraska football team had an all-time winning percentage of less than 62 percent, had just two winning seasons in the previous 20, and six consecutive losing seasons in a row.

Dye promised publicly upon accepting the position that he would turn Nebraska into a national football powerhouse, and went about it by plucking out of the University of Wyoming a 42-year-old head coach named Bob Devaney, who had gone 35-10-5 (.750) in his five seasons leading the Cowboys.

Devaney had not been Dyes first choice. He first offered the job to Utahs Ray Nagel and then to Utah States John Ralston after Nagel turned him down. When Ralston also said no, Dye turned to Devaney. Dye could not have been luckier.

Devaneys first Nebraska team went 9-2 and defeated Miami in the Gotham Bowl in New York. That marked the first of 40 consecutive winning seasons at Nebraska, the first 10 of them coached by Devaney, who went 101-20-2 and won eight conference and two national championships (1970-71) before turning the program over to Tom Osborne.

Dye obviously did not coach those teams, but he became a revered figure in Nebraska for hiring the man who did, and especially for shaping what became a winning tradition at the Lincoln school.

Dye didnt have as much success remaking what had been an awful Nebraska basketball program, but he made it a respectable one after hiring one of his former Washington players, Joe Cipriano, as head coach in 1964.

Cipriano, a key member of the 1953 UW Final Four team, presided over Cornhusker basketball until his death from cancer in 1980 at the age of 49. He produced a decent record 253-197 (.562) and two 20-win teams (Cipriano is one of two Seattle natives enshrined in the Nebraska Sports Hall of Fame, the other being former O’Dea sprinter Charlie Greene).

By 1967, Dye figured he had accomplished all he could at Nebraska, and decided to move on, landing as athletic director at Northwestern ($20,000 per year), a position held until 1974, when he retired. He said that he and his wife, Mary, whom he had followed to Ohio State in 1933, decided to settle in Port Charlotte, FL. Dye was 59.

After Mary, his wife of 64 years, died in 2001, Dye relocated to Camptonville to live with the family of his daughter, Penny. He doesn’t do much now — reads a lot and watches TV — but still gets outside for a daily, half-mile walk.

“I feel good, fortunately,” said Dye, who will turn 97 April 1. “I’m alert, or semi-alert, but I can’t remember anything anymore, and I have a hard time hearing. My health is good and I’m in pretty good shape. I hope I’ll last a little longer.”

However long he lasts, Tippy Dye’s has been remarkable life, and one fabulously lived.

———————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com