Note: Upon the death Monday of Elgin Baylor, 86, one of the greatest players in NBA history, we re-post a Wayback Machine feature from 2012 by Dave Eskenazi and Steve Rudman on Baylor’s time at Seattle University when the then-Chieftains were the darlings of the 1958 NCAA tourney.

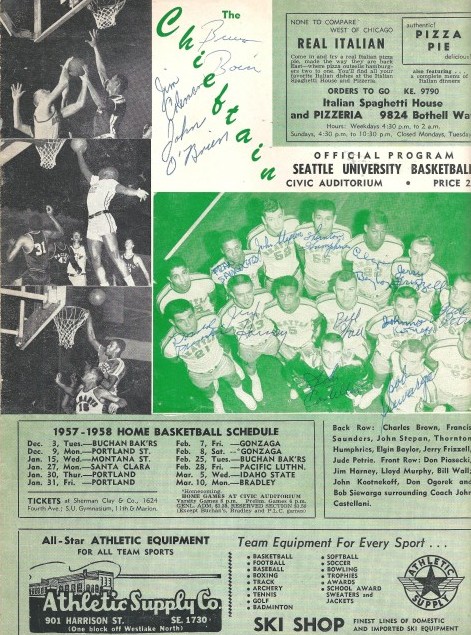

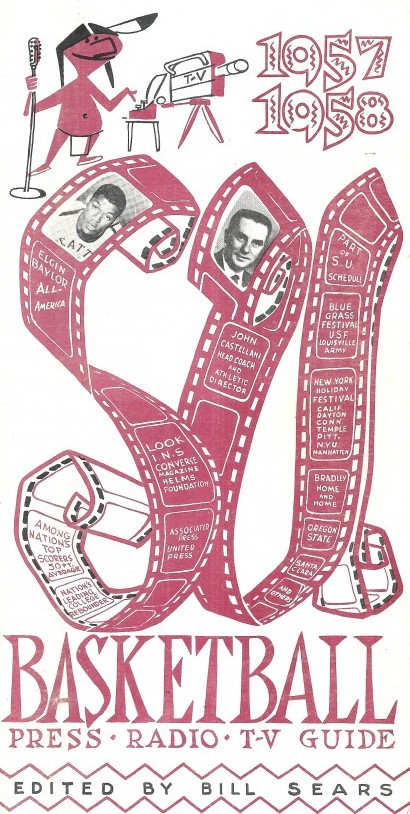

As far as can be determined, John Castellani still holds a dubious state coaching record that has gone unchallenged for more than 50 years: Most times hung in effigy in a single college basketball season. Castellani’s two lynchings occurred in 1957-58 when he mentored the Seattle University Chieftains (now Redhawks), a remarkable team led by the incomparable Elgin Baylor.

While more research is probably required, we also feel confident in avowing that Castellani is the only basketball coach in state history to get strung up (from a fire escape on the Seattle U. science building) after posting a 22-3 record (1956-57) and a No. 5 national ranking.

Although there is no official record for it, Castellani might be the only coach in Northwest annals to dangle from a utility pole twice in a nine-game span.

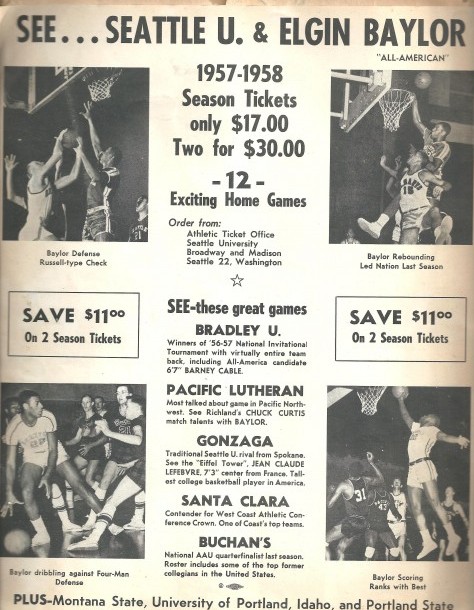

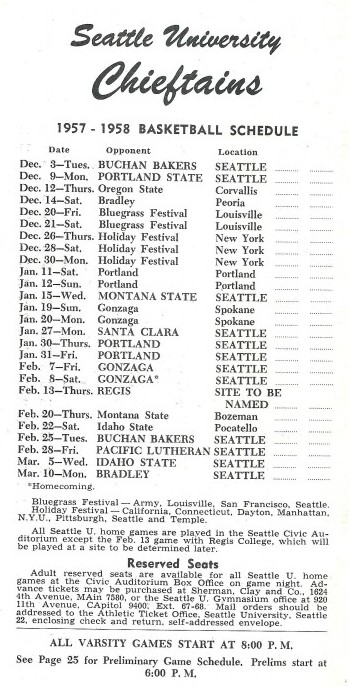

Those would have been the first nine games of the aforementioned 1957-58 season, when the Chieftains, despite Baylor’s routine airborne theatrics and every-game statistical absurdities, started out 4-5.

Among the setbacks: a season-opening loss to the Northwest AAU League Buchan Bakers, an 18-point tumble to lowly Temple, and a loss to Phil Woolpert’s San Francisco Dons after holding a late, eight-point lead.

This is not what Seattle U. enthusiasts had in mind, nor was Castellani the kind of coach they, or his players, had in mind.

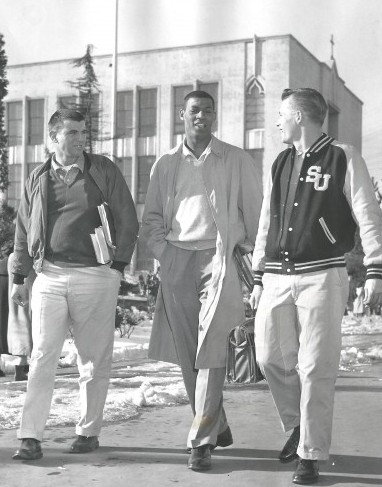

With some trepidation, Castellani arrived in Seattle in advance of the 1956-57 season from Notre Dame, where he had served as a scouting assistant under head coach John Jordan.

Castellani inherited a team, assembled by his predecessor, the popular Al Brightman, that had been broadly acclaimed as one of the best in the school’s history, even before it pulled on its shoes.

Castellani faced a dilemma not altogether new in the coaching dodge: If the Chieftains lost, obviously it was his fault; if they won, it was in spite of him.

Although the Chieftains won 22 games and lost only three in his first year, a rumble sounded on and off campus throughout the season that the 32-year-old half-Irish, half-Italian, fast-talking Castellani was too aloof and too much of a disciplinarian — one Seattle sports columnist described Castellani as having a bundle of off-putting complexes — to command the respect and confidence his players had accorded Brightman, a regular guy who had an infectious personality.

Brightman was only 24 when the Rev. A.A. Lemieux, SU’s new president and a priest who would transform the school into a major academic (and athletic) institution, hired him in 1948.

Brightman played some ball at Cal State Long Beach, but had not graduated. He had briefly been a member of the original (1946-47) Boston Celtics (Chuck Connors, later TV’s Rifleman, was one of his teammates) and spent one year playing for the Seattle Athletics (see Wayback Machine: Seattle Athletics).

With an enrollment of 2,200 students, Seattle U. barely had a basketball program in 1948, and when Rev. Lemieux brought Brightman aboard, he had one request: Al, the Jesuit scholar said, If were going to play basketball, let’s play it well.

Didn’t happen right away. Brightman’s first two teams went 12-14 and 12-17, after which Brightman’s most famous recruits, twins Johnny and Eddie OBrien, became eligible.

To capitalize on what the twins did best, Brightman installed a fast-break style of play (radical for its time), and shifted the 5-9 Johnny O’Brien to the pivot.

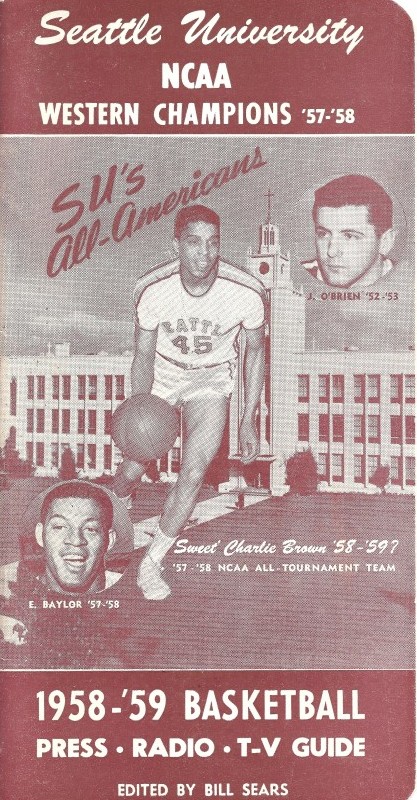

Brightman and the O’Brien twins posted records of 32-5, 29-8 and 29-4 (90-17 overall) in their three seasons together, no single win bigger than Jan. 21, 1952, when Johnny OBrien went for 43 points in a stunning upset over the then-serious Harlem Globetrotters (see Wayback Machine: Seattle U. Shocks The Globetrotters).

More than any other, that victory, which generated headlines across the country, turned Seattle U. from regional also-ran into a national power and made Johnny O’Brien a local athletic icon.

Brightman’s Chieftains didnt slow down after the OBrien twins graduated and signed major league baseball contracts with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Attracting quality players such as 6-6 forward Stan Glowaski (1952-55), Wayne Sanford (1952-55), 6-9 center Joe Pehanick (1952-54), Cal Bauer (1953-56), and Dick Stricklin (1954-57), the Chieftains played as if the O’Briens never left.

Stricklin served as the principal bridge between the O’Brien twins and Baylor, finishing with 1,595 career points (eighth on the school’s all-time list) and 924 rebounds (fourth). He also led his teams to two NCAA tournaments as well as the 1957 National Invitational Tournament.

Pehanick became one of Brightman’s major successes. He had not played high school basketball and went to work in Pennsylvania coal mines after graduating. Brightman ran across Pehanick when the SU freshmen played against a barnstorming AAU team that included Pehanick.

Brightman brought Pehanick to SU. and sat the would-be center on the bench for two years. On the rare occasions that Johnny O’Brien came out of a game, giving Pehanick a chance to play, Pehanick usually stumbled all over the place, once famously stubbing his toe on and tripping over a foul line.

But by 1953-54, his awkwardness gone, Pehanick had not only become a formidable center, but the top scorer on the West Coast.

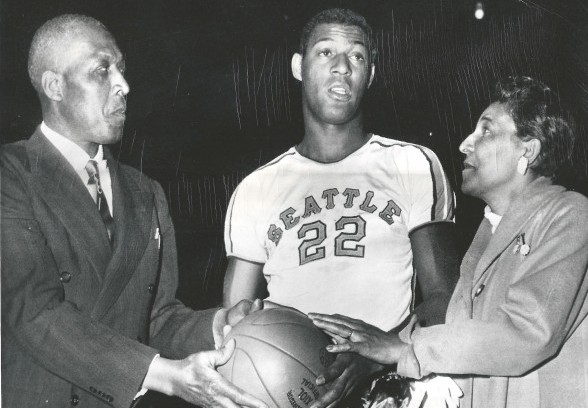

In the three post-O’Brien seasons, Brightman produced records of 26-2, 22-8 and 18-11. That 18-11 mark would have been better had Baylor been eligible, but he spent 1955-56 sitting out after transferring from the College of Idaho. Baylor played that year for an AAU team, Westside Ford. (See Wayback Machine: A Bakery That Cooked Up Basketball).

Brightman had the opportunity to coach Baylor and Sweet Charlie Brown, who would become an All-American in 1958-59, and although he recognized he would have one of his strongest teams, Brightman resigned in March 1956, following a 94-70 loss to UCLA in the NCAA Tournament, explaining he completed his work at Seattle U.

”I am leaving the school with what I believe are the makings of a fine team,” Brightman declared as he exited with a record of 180-86 and four NCAA Tournament appearances. ”I hope that my successor will have a fine record.”

So as Brightman, who also doubled as the first base coach of the Seattle Rainiers (see Wayback Machine: Rainiers & Pitchers Of Beer) in 1954, went off to manage a semi-pro baseball team in Edmonton, SU launched a search for his successor, which resulted in the hiring of Castellani, who had never set foot in Seattle before accepting the job and admitted after taking it that he had never heard of Elgin Baylor.

The various effigy episodes, plus the fact Castellani became the object of campus scorn and comic imitators, may have played into it, but Castellani eased off his hard edge after the 4-5 start, and finally gained enough control of himself and his players that SU was able to make one of the more remarkable sports runs ever witnessed by the city’s hoops cognoscenti.

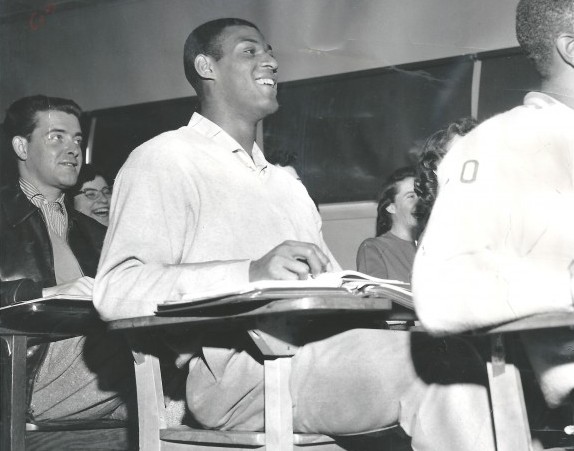

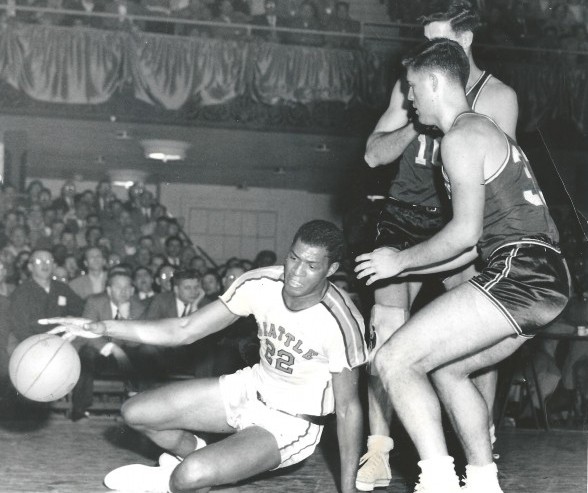

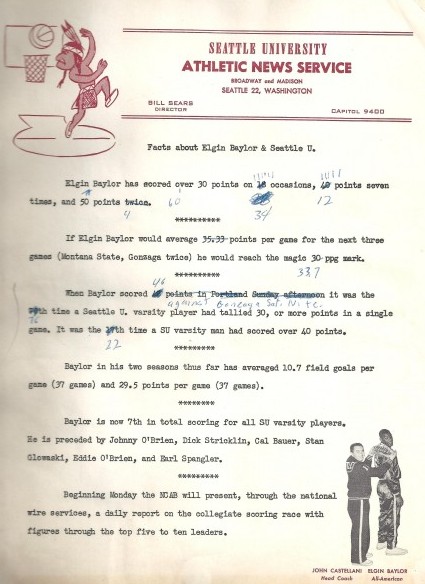

Baylor became the primary show, putting up double-doubles that seem unfathomable today: 53 points, 22 rebounds against Montana State; 60 points, 14 rebounds against the University of Portland; 43 points, 22 rebounds in a rematch with Portland; 42 points, 19 rebounds and 46 points, 30 rebounds in a pair against Gonzaga; 51 points, 37 rebounds against Pacific Lutheran.

Baylor finished 1957-58 with a 32.51 ppg scoring average, second nationally to Oscar Robertson’s 34.76 and well ahead of Wilt Chamberlain, who averaged 30.1 for Kansas.

(After Baylor dropped 60 on Portland, its coach, Al Negratti, jokingly told Castellani, “John, we almost had you. If we could have held Baylor to 54 points, we’d have won.”)

Although Baylor dominated Seattle U basketball, the 1957-58 team included a number of capable players. Don Ogorek was the closest thing the Chieftains had to a post player. Just a sophomore, he filled out the lineup alongside Baylor and Jerry Frizzell at the forwards and Charlie Brown and Jim Harney at the guards.

A Chicago native, Brown usually came in second to Baylor in scoring and rebounding. Players such as Francis Saunders, Don Piasecki, John Kootnekoff and Thornton Humphries were the principal reserves.

But the perception persisted that the Chieftains were too much Baylor and nobody else, that all a Castellani team could do was run, shoot and pray, that the Chieftains had amassed a great record against a weak schedule, and that the so-called solid teams would kill SU.

SU opened NCAA Tournament play March 12, 1958, at the Cow Palace in San Francisco against the University of Wyoming.

From a 9-9 tie after three minutes, the Chieftains bounced out to a 16-9 lead, extending to 51-25 at halftime, with Baylor accounting for 17 points.

It was so one sided early in the second half that Castellani brought in his four-man bench crew. He pulled out Baylor with eight minutes remaining and Seattle U leading 72-44. Baylor scored 26 points and pulled down 18 of the Chieftains’ 60 rebounds in what became an 88-51 victory.

Two nights later at the Cow Palace, Seattle U. got the better of NCAA Regional co-favorite San Francisco 69-67, when Baylor swished a 40-foot shot with two seconds to play in front of 16,382, the largest crowd to witness a basketball game on the Pacific Coast.

Baylor’s 40-footer gave him 35 points (he also grabbed 20 rebounds), the most by a player against a Woolpert team. So ecstatic were Seattle U. fans that they swarmed the court, pulled Baylor off his feet and paraded him around the Cow Palace for nearly 10 minutes.

In addition to his long-distance heave, Baylor threw a 90-foot pass to teammate Jerry Frizzell for a layin with four seconds left to end the first half.

”It was the greatest one-man performance I’ve ever seen,” said California head coach Pete Newell, who watched in awe from the stands.

Educated conjecture had it that Newell’s Bears, the tournament’s other co-favorite, would overwhelm the Chieftains. The forecasters seemed near validation when Cal streaked to a 37-29 lead at halftime, holding Baylor to 10.

But after Cal led 48-41 six minutes into the second half, the Chieftains, suddenly and surprisingly, toughened defensively, forcing Cal into a spate of turnovers. Seattle U. also capitalized at the line, hitting 18 of 19, including 14 in a row.

Saunders sparked the comeback, scoring 10 in a 13-minute span. With 12 seconds to play, Charlie Brown scored from 15 feet, sending the game into overtime. With 10 seconds left in OT, Brown hit from 25 feet to clinch a 66-62 victory, making SU the West representative in the NCAA Finals in Louisville.

When the team’s flight arrived at Sea-Tac Airport after the victory, 6,000 fans greeted the first West Coast at-large NCAA Tournament entry since Santa Clara in 1951, and just the third team from the state of Washington (also WSU in 1941 and UW in 1953) to reach the national semifinals.

Over the next few days, Baylor created a minor furor when he asked that he be allowed to play for the Buchan Bakers in the National AAU Tournament in Denver the week before the Final Four. Castellani denied him, saying that was against school policy, although Castellani couldn’t produce any evidence that such a policy existed.

Baylor further enlivened matters when he mulled over – and ultimately rejected — a $20,000 offer to join the Globetrotters.

No one expected much out of Seattle U. in Louisville except the Chieftains, who underscored the confidence they had by knocking off heavily favored Kansas State 73-51 in the national semifinals at Freedom Hall.

The Chieftains held K-State All-America selection Bob Boozer to 15 points, while Baylor, hurting from a bashed rib sustained in a collision with Boozer, had 23 points and 20 rebounds. Charlie Brown supplied 14 points.

Baylor delivered an ultimate humiliation near the end of the game when, trapped on the sideline, he coyly bounced the ball off the head of a defender, recovered it and drove in for an easy basket.

With three big tournament wins, Seattle U. became the third Pacific Northwest team to qualify for the national final, following Oregon, which won in 1939, and Washington State, which didn’t, in 1941.

Seattle U. might have prevailed against Kentucky in the title game if Castellani, a second-year head coach, hadn’t had the misfortune of trading Xs and Os with Adolph Rupp.

Analyzing matters, Rupp concluded he had no way, either in terms of height or skill, to thwart Baylor’s offensive versatility or his unstoppable rebounding.

No coach had solved Baylor in either area in two years, and Rupp didn’t solve them either, in the early minutes of the game.

With Seattle the only city in the nation watching the game live on television, the Chieftains roared from a 10-10 tie to a 21-16 edge, and looked like they might mop the planks with Rupp’s Wildcats after increasing their lead to 11. But after Baylor drew his third personal, Castellani immediately slowed the pace to a virtual walk in an attempt to keep the Wildcats from further troubling his star forward.

“When that (Baylor’s third foul) occurred, we quit running and lost all our momentum and eventually the game,” said Harney, the only senior on the SU roster. “We were extremely upset after the game. We felt they (the Wildcats) were the weakest of any of the teams we faced.”

Rupp plotted a strategy for taking Baylor out of the game. This is how Sports Illustrated reported it:

Rupp did it through a young man named John Crigler, easily the most underrated player in this tournament. Rupp set up fast-moving patterns that forced Seattle into a continuous switching of defensive assignments until Baylor was left guarding Crigler, and Crigler was left with the ball.

So far so good and, actually, not too difficult to accomplish. At the moment Baylor was forced to switch to Crigler, Crigler had taken advantage of an intricate series of legal screens and was already a half-step ahead of Baylor and driving on a clear path to the basket.

Baylor had to concede two points each time, or try to stop Crigler without fouling him. In a tournament game, players like Baylor concede nothing, and rightly so. But he could not avoid the fouls, and before the game was 10 minutes old he had three.

The issue was decided with a full 30 minutes to go.

Baylor tried desperately to avoid committing himself on a defensive assignment until the last second, and his teammates ran themselves to exhaustion trying to help him. Kentucky continued to get the ball to the man that Baylor was finally stuck with, and Baylor was obliged to choose between giving that man plenty of room, or pressing him hard and risk fouling out.

In the second half, Castellani tried to fend off the inevitable by putting his team in a zone defense. He had four men out front, running furiously to cover five while keeping Baylor under the basket where, at least, he was of value rebounding. There was a free Kentucky player outside, Whether it was the sharpshooting Johnny Cox in a corner, or the excellent jump-shooting Vernon Hatton (who scored 30 points) near the top of the key, he scored.

Handicapped both by fouls and the rib injury that left him gasping in pain, Baylor still scored 25 points, passed well and snatched a game-high 19 rebounds. But Kentucky won, 84-72.

The NCAA Tournament committee named Baylor the Final Four Most Outstanding Player player despite the fact he played on the losing team. Baylor became only the fourth non-winning player to earn the award. Rupp, who had never coached an African-American, said, ”We beat a wonderful team, as fine a team as we met all year.” Rupp made a special trip to the SU locker room to shake Baylor’s hand.

After the loss, which gave the Chieftains a 24-7 record, Castellani credited Rupp for his tactics with regard to Baylor, but in his own defense said, ”He (Rupp) has 600 wins. I have, what — 60?”

Castellani never got another as a college head coach. Just a month after the championship game, NCAA violations came to light concerning airfare purchased for recruits Ben Warley and George Finley. Castellani resigned under fire, Baylor left for the NBA (he made the announcement on the Ed Sullivan Show that featured the Look magazine All-America team), and the Chieftains were slapped with a two-year postseason ban.

Castellani spent one other season in basketball, ironically serving as head coach with the Minneapolis Lakers in 1959-60, when their star player was, of course, Baylor. After that, he moved to Milwaukee, passed the bar exam, practiced law for many years, and became a big fan of the Milwaukee Bucks and Marquette Golden Eagles.

Hero of the Western Regional win over California, Charlie Brown led the Chieftains in scoring in 1958-59, after Baylor departed, and finished with 872 points and 534 rebounds in two years. After graduation, Brown returned to Chicago, where he founded the Windy City Senior Basketball Leagues.

Several of the 1958-59 Chieftains later played with the Buchan Bakers, including Frizzell, who averaged 9.7 points and 5.8 rebounds during his SU career and entered the schoo’ls Hall of Fame in 2010.

Brightman, who recruited the players who made the run to the championship game, later coached the Anaheim Amigos of the American Basketball Association (1967-68). He died of liver cancer on June 10, 1992, in Portland.

4 Comments

Great story, great moments in Seattle sports history.

Couple of notes: Baylor didn’t play for the Buchan Bakers, it was Westside Ford, a team formed by an SU alum. Had he played for Buchan’s he would have gone to the Olympic Games that year. Charlie Brown, drafted by the Cincinnati Royals, instead went on to play for the Buchan Bakers in the National Industrial Basketball League. And John Castellani, not an Xs and Os guy, actually was the head coach of the Minneapolis Lakers, not an assistant.

Great story, great moments in Seattle sports history.

Couple of notes: Baylor didn’t play for the Buchan Bakers, it was Westside Ford, a team formed by an SU alum. Had he played for Buchan’s he would have gone to the Olympic Games that year. Charlie Brown, drafted by the Cincinnati Royals, instead went on to play for the Buchan Bakers in the National Industrial Basketball League. And John Castellani, not an Xs and Os guy, actually was the head coach of the Minneapolis Lakers, not an assistant.

Very interesting piece. Thanks for the research and excellent attention to a great period of Seattle sports history. Elgin Baylor has been making trips to Seattle as Seattle U continues to rebuild its basketball program at the Division I level.

I’d welcome a piece that examines Baylor’s style of play. Many of a certain age who grew up in Seattle say they had never seen a player do what he did. So was he the foundation of a “above the rim” style that led to Dr. J to Michael Jordan? In other words, to what extent did Baylor influence how the game was played?

Thanks for the good work.

Very interesting piece. Thanks for the research and excellent attention to a great period of Seattle sports history. Elgin Baylor has been making trips to Seattle as Seattle U continues to rebuild its basketball program at the Division I level.

I’d welcome a piece that examines Baylor’s style of play. Many of a certain age who grew up in Seattle say they had never seen a player do what he did. So was he the foundation of a “above the rim” style that led to Dr. J to Michael Jordan? In other words, to what extent did Baylor influence how the game was played?

Thanks for the good work.