By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Emmett Watson, later to become one of Seattle’s most popular and prolific daily newspaper columnists, as well as one of its most eccentric celebrities (CEO of Lesser Seattle Inc., whose motto was “KBO,” or “Keep The Bastards Out”), spent the afternoon of May 16, 1948 at Sicks Stadium covering that day’s baseball entertainment between the Seattle Rainiers and Sacramento Solons. Watson filed this report for the consumption of Seattle Times readers:

Little Mike White, Jo-Jo’s eight-year-old son, looked up at the scoreboard in the sixth inning of yesterday’s second game of a doubleheader between Seattle and Sacramento.

“‘Jeepers,’ he exclaimed, ‘Sacramento hasn’t even got one ——- !’

“Four hands, belonging to four different Rainiers players, clapped over his mouth. Mike almost committed the cardinal sin of baseball when a no-hit, no-run game is in sight — he tried to mention it.

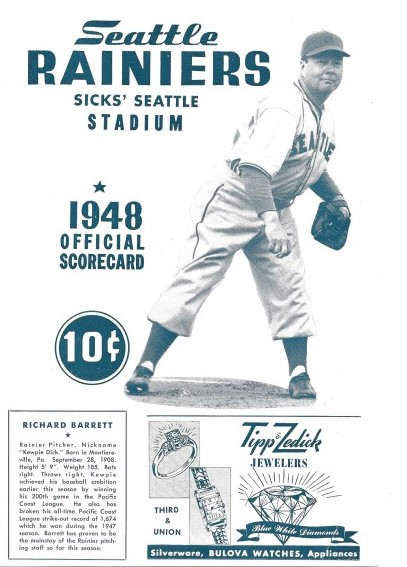

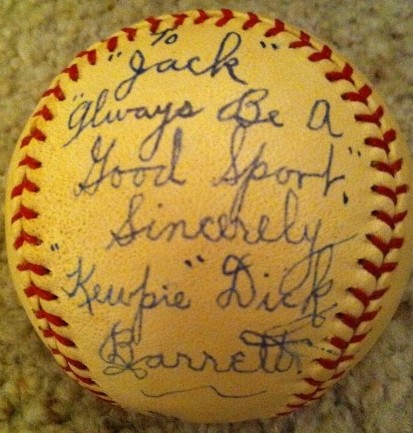

The man on the mound for Seattle, 41-year-old “Kewpie” Dick Barrett, had never thrown a no-hitter, much less a perfect game, in 799 Pacific Coast League starts.

The closest Kewpie Dick had come was a one-hitter against the San Francisco Seals nine years earlier, in 1939.

”When you can’t do it in 799 games, I guess it just isn’t in the books,” Kewpie Dick would say later. ”But they all look the same in the won-and-lost column. I’d rather win 10 two-hitters than win a no-hitter and lose a no-hitter.”

By the time Kewpie Dick stood on the precipice of becoming the second man in Pacific Coast League history to toss a perfect game — Cotton Pippen did it for Oakland against Sacramento May 31, 1943 – Barrett was in his 24th year of professional baseball. He pitched for pay since he was 18, when he signed his first professional contract, with the Williamsport Grays of the New York-Penn League.

Neither Barrett nor the 6,945 fans at Sicks Stadium realized it, but this would be the last full season for Kewpie Dick in a Seattle uniform, and also one of the last of his vast array of big baseball moments as an active player.

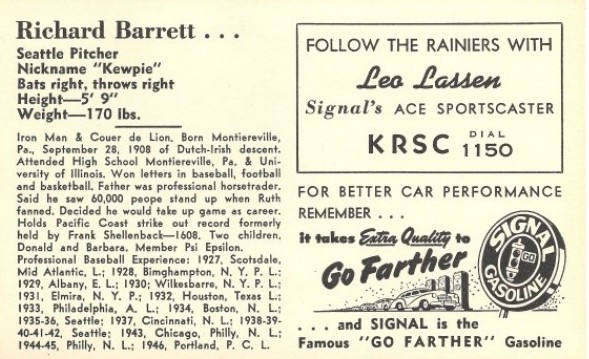

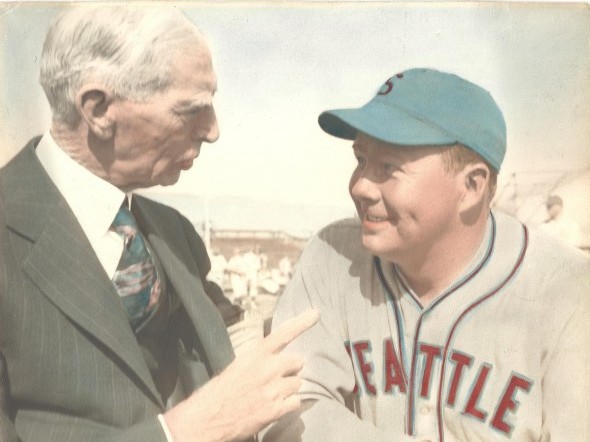

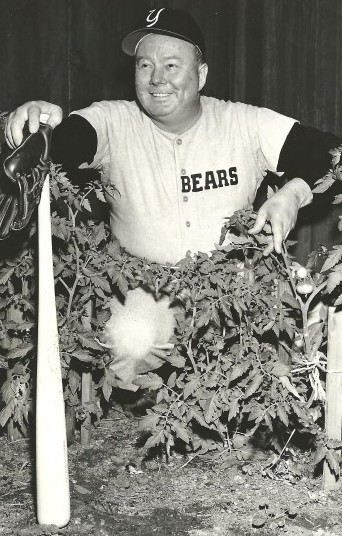

Born Sept. 28, 1906, in Montoursville, PA., Tracy Souter Barrett generally packed 190 to more than 200 pounds on a 5-9 chassis, which made him look like a dimpled, roly poly frump, and one of the most unlikely-looking ,perfect-game candidates that Watson, for one, had ever seen.

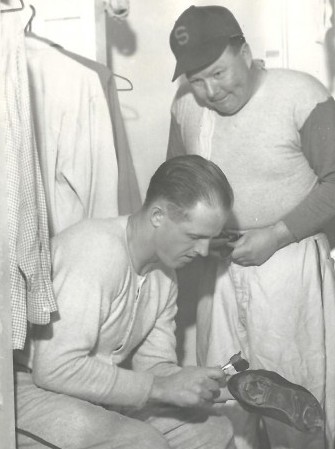

But Watson had a deeper appreciation for the cherubic Barrett. Six years earlier, Watson served as the bullpen catcher for the Rainiers and knew what Kewpie Dick could do with a baseball.

”He had a curveball that bowed like a head waiter,” Watson wrote. ”You could almost hear it when it broke.”

Kewpie Dick spent his first eight professional seasons laboring in the low minor leagues, with Williamsport (Class B, 1925), Scottsdale (Class C, 1926-27, Middle Atlantic League) and Binghamton and Albany (Classes B and A, 1928, New York-Penn and Eastern League).

In 1929, Barrett pitched for four teams Class D Chambersberg (Blue Ridge League), Class B Wilkes-Barre (New York-Penn League), Class A Albany (Eastern League) and AA Jersey City (International League). Between 1930-32, Barrett saw action with five more teams, hardly distinguishing himself. During that span, Barrett won just six games while losing 34.

During that span, Barrett, obviously a Type A personality, became a three-sport athlete at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne, playing football, basketball and baseball. In the first semester of his senior year, Barrett decided to play pro baseball full time. He adopted the name Dick Oliver, which he used for the 1933-34 seasons (he did not want it known that he played baseball for pay and then performed as an amateur at IU-Champagne).

But when word of his pro baseball activity got out, UI Urbana-Champagne stripped him of his varsity letters. By the time that happened, Dick Oliver was long gone from Illinois.

Barrett received a spring training tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1933, failed to stick, and signed with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics as a free agent. Unlike the Cardinals, Mack thought enough of him that he gave the 25-year-old Barrett a chance to pitch in the big leagues two months into that season.

Barrett made his major league debut June 27, 1933, receiving a no-decision in an 8-3 loss to the Chicago White Sox. He recorded his first major league win July 5, 1933, beating the Boston Red Sox 4-2 at Shibe Park by tossing a complete game while striking out eight.

For the next two years, Barrett pitched for the Athletics, Jersey City of the International League and the Boston Braves, doing little to distinguish himself and enough to convince Bill McKechnie, who ran the Braves, that he probably was not major-league ready.

On Nov. 24, 1934, McKechnie, figuring hed seen enough (6.68 ERA in 15 starts), sent Barrett, along with Dick Gyselman and Clarence Pickrel, to the Seattle Indians for third baseman Coffee Joe Coscarart. Barrett arrived in the Queen City with a major league record of 5-7 and an ERA of 5.78 in 30 appearances, which included 10 starts. His best performance: a complete-game, 11-3 victory over the St. Louis Browns at Sportsmans Park Aug. 25, 1933, in which Barrett allowed nine hits.

In his years in the minors (and majors) Barrett put together one outstanding season, a 20-9 record for Class B Binghamton in the New York-Penn League in 1928. Otherwise, he was a .500 pitcher without much to recommend him.

“Barrett is just a guess,” wrote the Seattle Times when it reported the trade (which became one of the most significant in the history of the Indians/Rainiers franchise). ”But he is supposed to be a smart chap with the ability to win in the Coast League.”

The Times appeared ready to retract that assessment after Barrett, creating major angst among the citizenry, started out the 1935 season 0-6. But Kewpie went 22-7 the rest of the way for an Indians team that finished 80-93. That was only a prelude of the greatness to come.

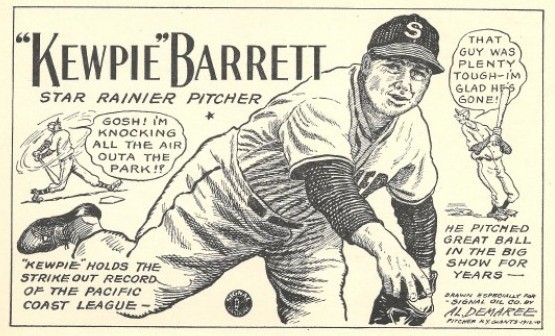

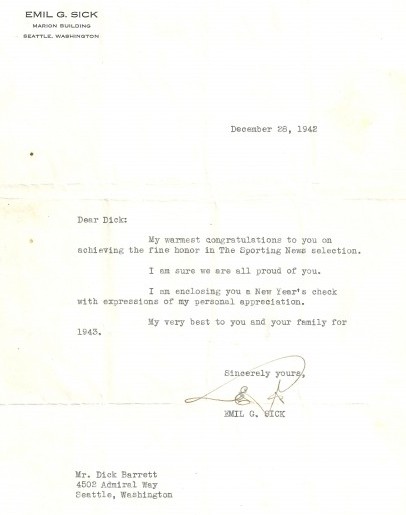

With that prelude, Kewpie Dick won 20 or more games in seven of his first eight years in Seattle, topped by a 24-5 record in 1940, when the Rainiers captured the second of three consecutive Pacific Coast League pennants, and a 27-13 (1.72 ERA) mark in 1942, the year The Sporting News named him the Minor League Player of the Year and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer designated him its “Man of the Year” (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of the Year: 1935-49).

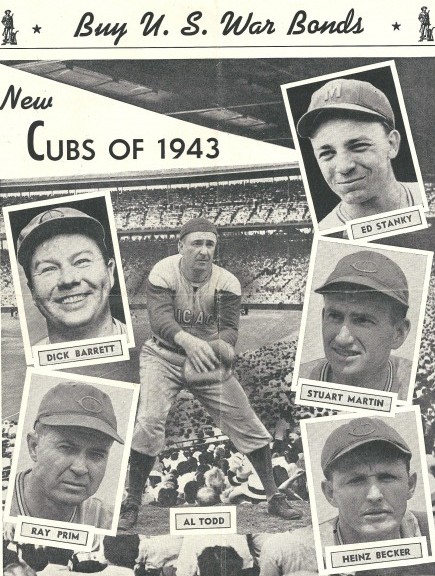

On Nov. 2, the Chicago Cubs selected Barrett in the Rule V Draft (he was selected in the 1936 Rule V Draft by Cincinnati, but returned to the Indians). Barrett spent the ensuing three seasons with the Philadelphia Phillies after they purchased his contract from the Cubs, who were not enamored with Barrett’s 0-4 start to the 1943 season.

Barrett responded to the jilt with a 14-inning, complete-game, 1-0 win over the Cincinnati Reds July 8, 1943 at Philadelphias Shibe Park, and pitched an 11-inning, complete-game, 3-2 win over Stan Musial’s St. Louis Cardinals Sept. 26, 1943.

On June 1, 1944, Barrett ripped a triple and a double and pitched Philadelphia to an 8-7 win over Cincinnati.

A month later, he threw a complete-game two-hitter against the Cubs at Wrigley Field.

Barrett had three hits in a game twice, Aug. 6, 1943, for the Phillies against Mel Ott’s New York Giants, and May 28, 1944, against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Barrett earned a spot in Philadelphia’s 1945 rotation, but went 8-20 (his 20 losses led the National League, as did his eight wild pitches) with a 5.38 ERA. He never received another real opportunity to pitch in the majors after that, and found himself back in the PCL in 1946, with Portland.

After one year with the Beavers, Kewpie Dick rejoined the Rainiers for his final go-round with the franchise in 1947.

In his extraordinary history of the Rainiers, Pitchers of Beer (see Wayback Machine: Rainiers & Pitchers of Beer), former Seattle Post-Intelligencer writer Dan Raley wrote that the main reason Kewpie Dick failed to succeed as a major leaguer was his addiction to drink, the only thing Kewpie Dick enjoyed more than pitching. Raley suggested he was swimming in a bottle.

Raley also quoted a number of Kewpie Dick’s Seattle teammates to the effect that there was no telling how good a pitcher he could have been had he not been such a lush.

Scan Kewpie Dick’s pitching record today, especially the years 1938-42 when he went 111-62, and you would never suspect he had a problem.

Fans who watched him in the flesh may not have suspected a problem, either, considering his longevity and willingness to pitch (he averaged 300 innings per year in his best seasons with the club).

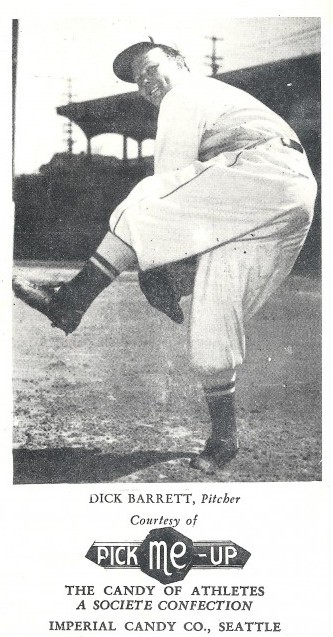

Asked how he still got batters out after turning 40, Barrett said, ”First, I make my leg, back and shoulder do most of the work. Second, I stick pretty much to the old routine — the same form and rhythm, the same pitches: two curves, a fast one and a change.

“I stay away from screwballs, knuckleballs and the rest and only rarely throw a slider. So my muscles and bones and nerves just keep on doing what they’re used to. Third, I like it out there.

“I go for the corners. I don’t like to serve up fat ones. So most of them are close — strikes when I’m right, balls when I’m not, or when the umpire ain’t in a gimme mood. But I don’t mind having men on base. In fact, my teammates are always razzing me about it.

Future columnist Watson described Kewpie Dicks pitching style this way: “He never threw hard, but he knew where to put it.”

Five decades down the road, former Mariners catcher Dan Wilson (1994-05) would use almost the same words to describe his Seattle teammate, Jamie Moyer, who is still lobbing carefully placed pillows in his 49th year (Moyer turns 50 Nov. 18, making him eligible for an AARP card).

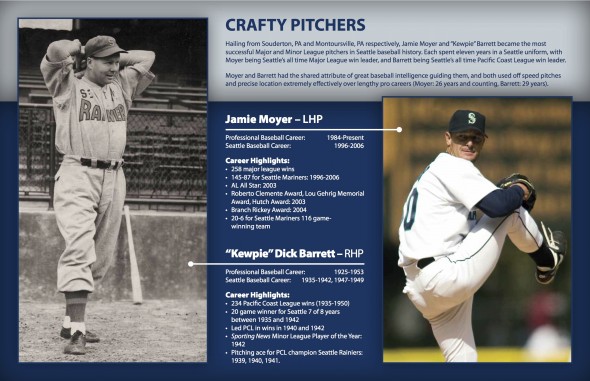

Given the similarities in the Barrett-Moyer pitching styles, among other things, the Mariners have used the pair as part of an exhibit at Safeco Field titled “Connecting Generations: Seattle Baseball Stars.”

Moyer and Barrett are the ”Crafty Pitchers” part of the display, and the similarities are striking. Both are Pennsylvania natives, Barrett hailing from Montoursville, Moyer from Souderton. They are the most successful minor and major league pitchers in Seattle’s long baseball history. Each toiled in a Seattle uniform for 11 years, Moyer finishing his Mariners career in 2006, when a trade sent him to Philadelphia, Barrett ending his in 1949.

When Moyer left the Mariners, he was the franchise’s all-time wins leader with 145. When Kewpie Dick departed the Rainiers, he was their all-time wins leader.

Barrett and Moyer used off-speed pitches and precise location to extend their careers, 29 years for Barrett, 25 seasons (and counting) for Moyer.

One difference: While pitching for the Mariners (1996-06), Moyer never faced the kind of circumstance that presented itself to Barrett May 16, 1948.

Remarkably, given his history (career PCL leader in walks), Barrett hadn’t put any runners on base heading into the top of the sixth inning that day.

According to Watson, Ernie Lombardi grounded to Skeeter Newsome; one out. Whitey Wietelman grounded to Barrett; two out. Emmett ONeill struck out; end of sixth.

The crowd of 6,945, including eight-year-old Mike White, knew exactly what was happening — it was watching Barrett pitch the first no-hitter and perfect game of his career. It was also watching the first no-hitter and perfect game in Sicks’ Stadium’s 10-year history.

“The top of the Sacramento order came up in the seventh,” Watson wrote. “Barrett got behind (two balls, no strikes) on Alex Kampouris. He got one strike over and then Kampouris fouled off a pitch. Ball three. The crowd roared as Kampouris missed a curve ball for the third strike.

”Next hitter: Al White, Solon center fielder. The second strike on White was a whistling ground ball that went foul off first base by inches. Strike three! Barrett was one out away.

“He worked the count to two strikes and a ball on Ted Jennings. Jennings always had given Dick trouble – a tough hitter. He fouled one off, then laced a ground ball at Tony York, who tossed to George McDonald for the third out. Final score: 3-0.”

Rainier players whacked, pummeled and almost mobbed Barrett as the crowd gave him a standing ovation.

The Solons hit three hard balls off Barrett. Jennings twice lined out to left, once to Earl Rapp in the first, and again to Jo-Jo White. Yorks’ leaping catch of Babe Dahlgren’s liner in the second was the only sensational play of the game. In the third, Barrett retired the side on four pitches.

”They say it was too bad that it was only a seven-inning game. But after 24 years of waiting for one to come along, I’ll settle for that,” Barrett said after notching his 204th PCL victory, and his 195th wearing a Seattle uniform.

A few months after Barrett’s perfect game, Baseball Digest wrote, ”To our notion, it’s the attitude more than the arm which keeps Kewpie going strong long after most of his early contemporaries had to call it quits.

“In the naughty past when men used to wager on ball games, Seattle was automatically a substantial favorite when it was Barrett’s turn to pitch. The gamblers wouldn’t even bother to ascertain the opposition. You couldn’t blame them.”

Pleased as he was with his perfect game, Kewpie Dick liked to tell people following his playing days that his top baseball thrill occurred in the 1941 PCL playoffs when he started five times in two weeks and notched four wins, including the deciding game of each series.

Barrett also thought highly of having thrown four openers in 1938 – the first game of the Rainiers season at San Diego, Oakland’s home start the following week, Seattle’s the week after at Civic Stadium, and then the first game played at Sicks Stadium when it was completed at midseason.

Almost as remarkable as Kewpie’s perfect game, and certainly more in character, was the fact that he pitched several doubleheader victories, including one on the closing day of the 1937 season when he needed two wins to reach 20 and collect a $500 bonus (he won both and got the bonus; Seattle manager Johnny Bassler lost his job for starting Kewpie in the nightcap when owner Bald Bill Klepper had expressly ordered him not to, in an attempt to save on expenses).

Kewpie simply loved to pitch. He won in 16 innings and lost in 15. Once, he won both ends of a doubleheader with complete-game shutouts (one of just 14 PCL pitchers to accomplish that feat).

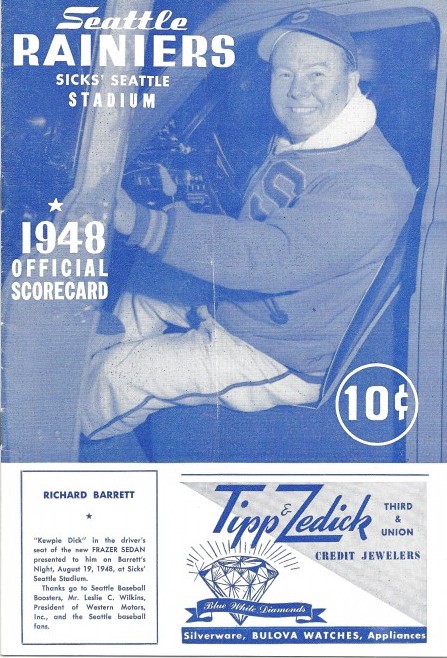

The next-to-last last hurrah for Barrett as an active player occurred Aug. 29, 1948, when the Rainiers saluted him on Dick Barrett Night at Sicks Stadium in front of a crowd of 8,006. Fans and club boosters presented Barrett with a new automobile, the Rainiers gave him a gold watch, and his West Seattle neighbors presented him with an expensive hunting gun.

Even the umpires and the opposing San Diego Padres made contributions, both humorous. The umps gave Kewpie Dick a three-foot wide home plate, and the Padres awarded him a glass arm.

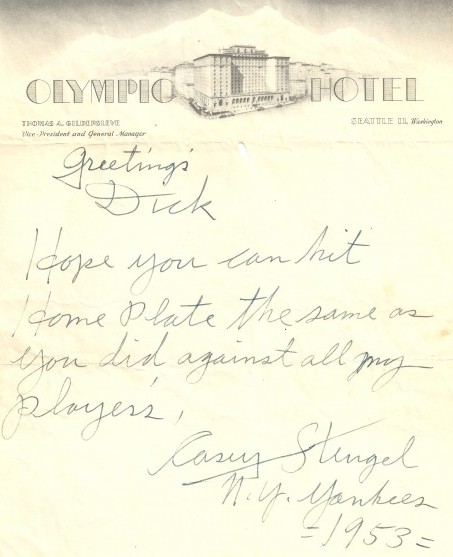

Fans cheered Barrett as gifts valued at thousands of dollars piled up before him, and several telegrams were read, including these two:

“Sincerely wish I could be present for your richly deserved night, but existing conditions make it impossible. Your 202 victories in a Rainier uniform is a record of which you can be proud.

“You have set an outstanding example of performances on our diamond, not only giving winning efforts with a high degree of consistency, by your great show of heart at all times. You have stamped yourself as one of the truly greats in Pacific Coast League history.”

Clarence Pants Rowland, commissioner of the PCL who managed the Chicago White Sox from 1915-18 (missing the Black Sox scandal by a year), signed that one. Former University of Washington football coach Jimmy Phelan (1930-41), who may have hit the bottle harder than Kewpie, signed this one: ”Congratuations, Dick. You have a great heart and a host of friends, and I am one of them.”

Ten months following his perfect game, June 6, 1949, having worked just 24 relief innings for the 1949 Rainiers, Barrett, who had ”lodged himself into the heart of almost every Seattle baseball fan (Seattle Times),” requested his release — and the Rainiers accommodated.

Kewpie Dick still wanted to pitch, but manager Jo-Jo White, a former teammate, lost confidence in him. Barrett immediately signed with San Diego.

Not quite a month later, June 30, Kewpie Dick returned to Sicks’ Stadium, drawing the starting assignment against the Rainiers.

Watson, who had chronicled Kewpie Dicks perfect game, once again delivered the missive.

“The Man came home last night to Sicks Stadium, to the park he wasn’t good enough to pitch in, where they wrote him off the payroll.

“The Man came back in the gray uniform of San Diego and sank the shiv right up to the handle. Then he broke it off.

“A casual visitor to the Rainiers front office after last night’s game would have had to watch his step, lest he trip over chins that were dragging the floor. Barrett affects some people that way.

“The Kewp, wearing the alien livery of the Padres, rubbed it into Seattle by the decisive margin of 6-2. For nine innings he was a proud little man proving a point, with the mound as his speakers platform.

“His didactics were a curve and a fastball, an occasional slider and a cautious change of pace. His stout competitive ability was his logic. His argument was irrefutable.

“Jo Jo White used 16 ballplayers in an attempt to knock the Kewp out of there. But all of Sicks’ horses and all of Sicks’ men couldn’t keep old Humpty-Dumpty from winning again.

“And he left the embarrassing total of 15 Seattle runners dying on the vine. Rubbing salt in the wound: Kewp picked up two singles and a walk in four trips.”

Kewpie Dick’s dis of his old ball club constituted one of his last great moments as a player.

From then on, clearly nearing the end, he had cups of coffee with Hollywood, Victoria, Yakima and Vancouver, and briefly managed the Victoria Athletics of the Western International League (1951). Kewpie Dick finished his PCL career with a league-record 1,866 strikeouts.

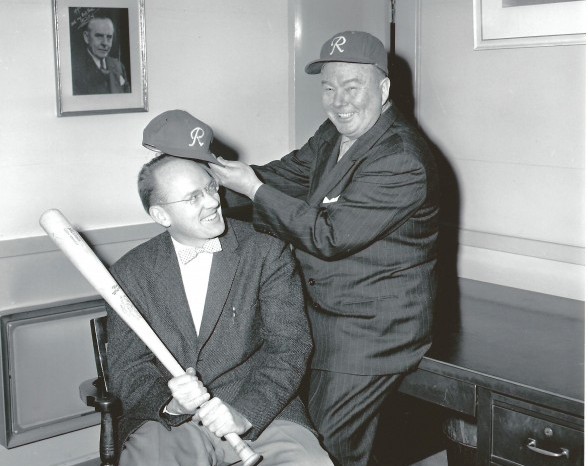

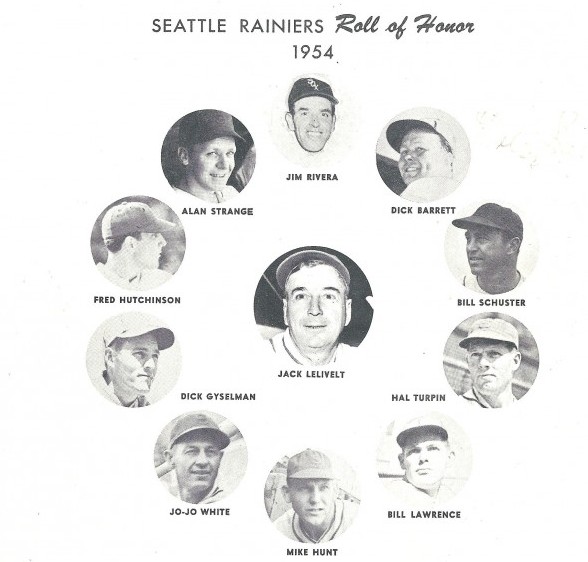

Three years later — Aug. 12, 1954 — Kewpie Dick received another summons to Sicks’ Stadium. Prior to a doubleheader against the Oakland Oaks, and with Rainiers color commentator Bill O’Mara serving as master of ceremonies, the Rainiers unveiled the franchise’s “Roll of Honor.” Selected by fans, this august group included 11 players.

O’Mara first reviewed the achievements of honorees unable to attend, Fred Hutchinson, Jungle Jim Rivera, Jo Jo White, Bill Lawrence former manager Jack Lelivelt (deceased) and then read telegrams from these men.

The honorees present included Kewpie Dick, Hal Turpin, Dick Gyselman, Alan Strange, Mike Hunt, and Bill Schuster, were then introduced to the 2,715 fans, who watched Seattle Bill James, star pitcher for Dan Dugdale’s 1912 champion Seattle Giants, presented the Rainier greats with handsome Roll of Honor trophies and large framed photographs of themselves (see Wayback Machines Seattle Struck Gold in Dugdale and Seattle Bill James and the 1912 Giants).

Fans had cast more votes for Kewpie Dick than any other Rainiers great. Two key players from the franchise’s championship years (1939-41), center fielder Lawrence and offensive sparkplug White, finished second and third in the voting, while Seattle’s favorite son, Hutchinson, came in fourth, despite having played for the franchise for only one season (1938).

Following that cameo, Kewpie Dick drifted far from the limelight.

After a brief stint in the Rainiers’ broadcast booth, Barrett went to work in a mill, then worked for the parks and recreation department, then became a ticket taker on the ferry system, and a restaurant greeter.

Then, in 1963, it came to light that Barrett was impoverished and suffering from diabetes.

The public came to understand his plight after Barrett was arrested for shoplifting chicken from a West Seattle grocery store because his $48 welfare check hadn’t arrived (Kewpie got a $50 fine).

The Post-Intelligencer, explaining that Kewpie Dick “had sagged under the burden of bad health and financial problems,” launched a fundraiser to help Kewpie Dick get back on his feet.

On Nov. 7, 1966, at about 11 a.m., Kewpie Dick’s wife, Dorothy, discovered her husband dead in his bed at 118 Tenth Ave. S.

Wrote Vince O’Keefe in The Times: “The once-blithe spirit died in his sleep, probably dreaming of pitching one, last, glorious no-hitter.”

———————————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi.Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

16 Comments

I was in the Sick’s Stadium crowd on the day that Kewpie Dick threw his masterpiece. Then 13, I was a baseball junkie and followed Rainier games avidly via Leo Lassen’s radio broadcasts. A friend called me the day before the game to say that his parents were driving from Bellingham to Seattle for the game and had an extra ticket. I of course signed on immediately.

Early on the morning of the game it was raining hard in Bellingham. My friend called; his parents might not be driving to Seattle after all, he said, because they did not want to risk a rainout. But

in the end we drove down to Sick’s Stadium. It was raining lightly in Seattle, too, but the show went on and skies lightened quickly. I can still Kewpie Dick’s unique windup. He was notorious for pitching full counts and for getting miraculously out of jams with runners on base.

This wonderful piece brought back memories of that earlier time. I rooted loyally for the Rainiers—Edo Vanni, Barrett, Jo Jo White, and all the other mainstays. The only exception was when

my Bellingham neighbor, Cliff Chambers, was in town with the Los Angeles Angels and pitched

against the Rainiers. My parents took me to one of his pitching starts at Sick’s Stadium.

We stayed in the old Gowman Hotel with the Angels and, after the game, Cliff gave me a ball autographed by him and his catcher, Joe Stephenson.

Keep these pieces coming. They bring back memories of simpler, often happy times.

Thanks so much for sharing those great stories, Ted. Steve and I very gratified that the Wayback Machine brings these memories back to life!

Dave Eskenazi

On behalf of David Eskenazi, thanks for reading. We’ve got more pieces in the pipeline.

I was in the Sick’s Stadium crowd on the day that Kewpie Dick threw his masterpiece. Then 13, I was a baseball junkie and followed Rainier games avidly via Leo Lassen’s radio broadcasts. A friend called me the day before the game to say that his parents were driving from Bellingham to Seattle for the game and had an extra ticket. I of course signed on immediately.

Early on the morning of the game it was raining hard in Bellingham. My friend called; his parents might not be driving to Seattle after all, he said, because they did not want to risk a rainout. But

in the end we drove down to Sick’s Stadium. It was raining lightly in Seattle, too, but the show went on and skies lightened quickly. I can still Kewpie Dick’s unique windup. He was notorious for pitching full counts and for getting miraculously out of jams with runners on base.

This wonderful piece brought back memories of that earlier time. I rooted loyally for the Rainiers—Edo Vanni, Barrett, Jo Jo White, and all the other mainstays. The only exception was when

my Bellingham neighbor, Cliff Chambers, was in town with the Los Angeles Angels and pitched

against the Rainiers. My parents took me to one of his pitching starts at Sick’s Stadium.

We stayed in the old Gowman Hotel with the Angels and, after the game, Cliff gave me a ball autographed by him and his catcher, Joe Stephenson.

Keep these pieces coming. They bring back memories of simpler, often happy times.

Thanks so much for sharing those great stories, Ted. Steve and I very gratified that the Wayback Machine brings these memories back to life!

Dave Eskenazi

On behalf of David Eskenazi, thanks for reading. We’ve got more pieces in the pipeline.

What I love about the Wayback Machine is it puts life into all these historic Seattle sports names I’ve always known but knew little about. Thank you.

On behalf of Steve Rudman, thanks very much!

Dave Eskenazi

What I love about the Wayback Machine is it puts life into all these historic Seattle sports names I’ve always known but knew little about. Thank you.

On behalf of Steve Rudman, thanks very much!

Dave Eskenazi

Another great Wayback Machine piece.

The thing about Barrett is that with all those innings he pitched, few of them were of the quick 1-2-3 variety. Mr. Sick couldn’t sell beer at the ballpark on Sundays, so he preferred seeing Hal Turpin (who worked very quickly) pitch on those days instead of Barrett (who was always pitching into and out of trouble).

Leo Lassen came up with a poem he’d recite when Kewpie Dick went to a full count on a batter (which happened often): “Roses are red, violets are blue, Barrett’s pitching, it’s 3-and-2.” Truly a character.

You certainly have a good grasp of Rainiers’ history, especially the part about no beer sales on Sunday. Imagine that today.

Another great Wayback Machine piece.

The thing about Barrett is that with all those innings he pitched, few of them were of the quick 1-2-3 variety. Mr. Sick couldn’t sell beer at the ballpark on Sundays, so he preferred seeing Hal Turpin (who worked very quickly) pitch on those days instead of Barrett (who was always pitching into and out of trouble).

Leo Lassen came up with a poem he’d recite when Kewpie Dick went to a full count on a batter (which happened often): “Roses are red, violets are blue, Barrett’s pitching, it’s 3-and-2.” Truly a character.

You certainly have a good grasp of Rainiers’ history, especially the part about no beer sales on Sunday. Imagine that today.

Kewpie Dick – You gotta love him, you gotta love Dave E. also!

Kewpie Dick – You gotta love him, you gotta love Dave E. also!