By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

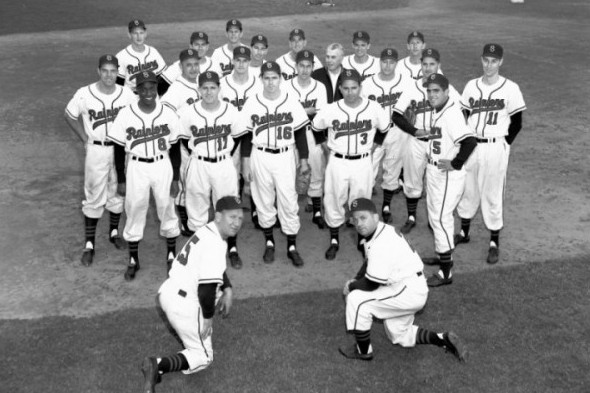

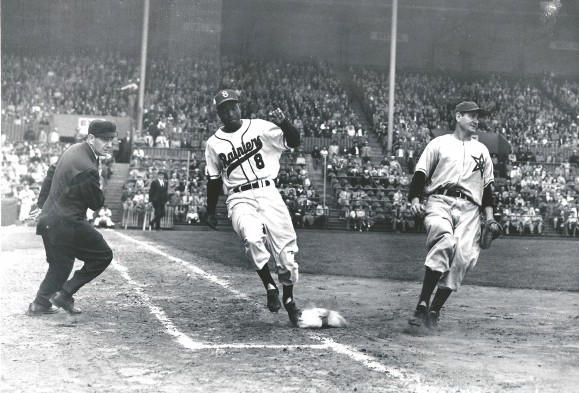

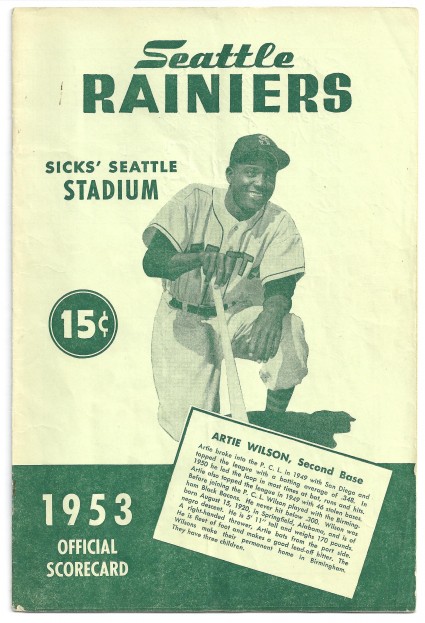

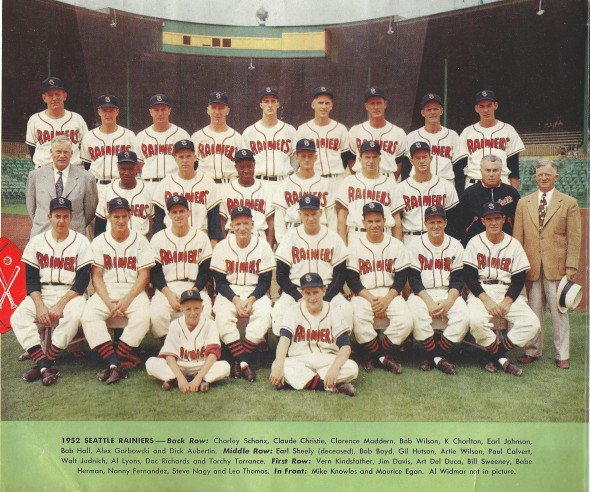

The Seattle Times devoted two pages and part of a third to the Seattle Rainiers April 16, 1952 home opener, held at Sicks Stadium against the Los Angeles Angels. The Times, as well as the rival Post-Intelligencer, typically made much of the pre-game festivities, which featured the usual introduction of players and short speeches by Seattle Mayor Allan Pomeroy and PCL Commissioner Clarence Pants Rowland, and printed three stories related to the contest itself, a 6-0 win in front of 12,000 fans.

Neither The Times nor the Post-Intelligencer mentioned anything about the fact that the Rainiers, five years after Jackie Robinson broke the major league color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and four years after Johnny Ritchey knocked down the PCL color line with the San Diego Padres, had integrated their club.

Perhaps the newspapers did not view the integration of the Rainiers as noteworthy, or perhaps they simply felt it prudent not to comment on what was still a highly charged issue (half of the major league teams still had not been integrated). Whatever the case, both Bob Boyd and Artie Wilson would have been hard to miss, African-American or not.

Wilson, who was up briefly with the New York Giants, led off and played shortstop. Boyd, two years earlier the first African-American to sign with the Chicago White Sox, hit second and played first base.

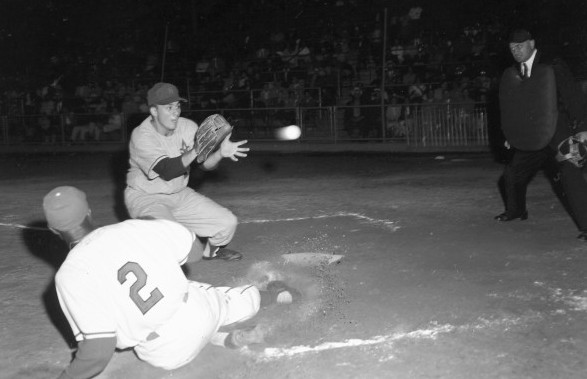

Wilson and Boyd came to Sicks’ Stadium that day with another distinction: They made their Rainiers debuts April 1 in a season-opening road game against the Hollywood Stars, each going 3-for-5, and by the time of the home opener, they ranked 1-2 in the PCL batting race, Wilson ahead by percentage points.

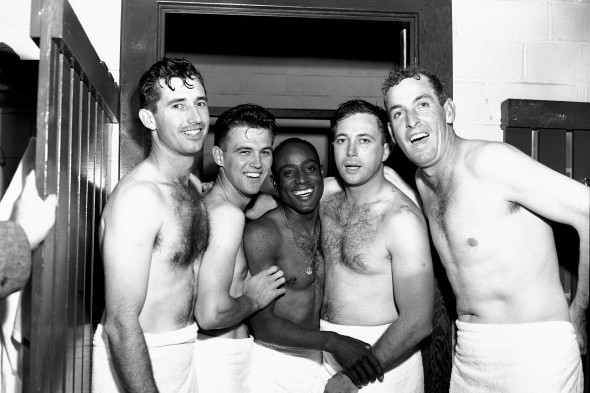

As the season played out, both newspapers remained color blind about the integration of the Rainiers, publishing nothing about how Wilson and Boyd were fitting in, or not, or how their teammates accepted them, or not. One spring training incident provides all we know. The Rainiers went to a dinner at a California restaurant, which refused to serve Artie and Boyd. In protest, all of the Rainiers got up and left the establishment.

Perhaps the papers had an enlightened editorial policy, or perhaps they figured their readers didnt want to read about integration, or maybe the papers just didn’t want to go there. Or, it could have been that the batting averages posted by the pair simply shut up those who had a mind to object.

“The fans were wonderful and I never had no problems, not even in some of the towns where other guys did,” Wilson told Dan Raley in his book, “Pitchers of Beer.” “Seattle was a nice place. The fans were awful good. Nobody mentioned race.”

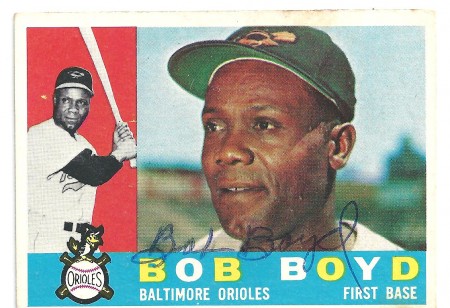

Whatever the case, add Boyd to the list of Seattles remarkable one-season wonders. Nicknamed “The Rope” for his propensity for hitting line drives, he ultimately edged Wilson for the PCL batting title, hitting .320 with 205 hits to Wilsons .316 with 216 hits.

Boyd took the batting title on the last day of the season, going 5-for-8 in a doubleheader against Hollywood while Wilson went 3-for-9.

After that, Boyd re-joined the White Sox, commencing what would become a nine-year run in the majors, leaving Seattle in his rear-view mirror.

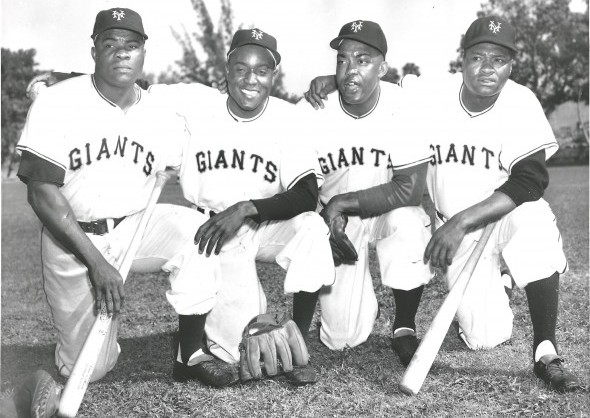

The 31-year-old Wilson, who appeared in 19 games for the 1951 Giants before losing his roster spot to 20-year-old Willie Mays, a former Birmingham Black Barons teammate, never got another shot in the majors, leading former Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda to remark long after Wilsons career ended, Artie Wilson is the greatest player to never play in the major leagues.

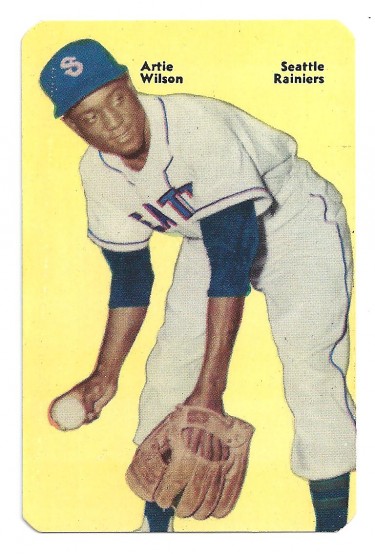

Bad for Wilson, good for the Rainiers, for whom he starred as a fan favorite in 1952, 1953, 1954 and 1956. Also bad for Wilson but good for the Rainiers: Wilson spent the 1955 campaign with the Portland Beavers, and it was in 1955 that the Rainiers, managed by Fred Hutchinson, won their last PCL pennant (see Wayback Machine: Hutch & The 1955 Rainiers).

Based on the statistics he amassed in a career that started in 1944 with the Barons of the Negro National League, and for some of his accomplishments, Artie Wilson should have received, many baseball researchers say, more of a chance to succeed at the major league level.

He didnt, for a variety of reasons, a relatively weak throwing arm being one of them, but mostly because not all teams had been integrated and those that had placed a quota on the number of blacks they employed at any time.

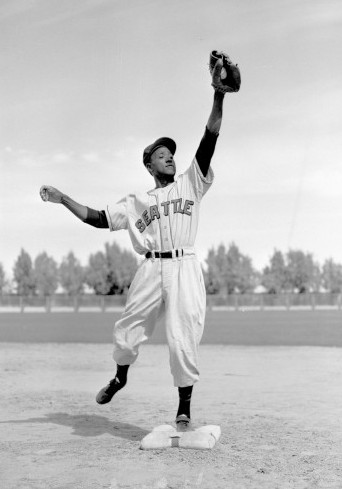

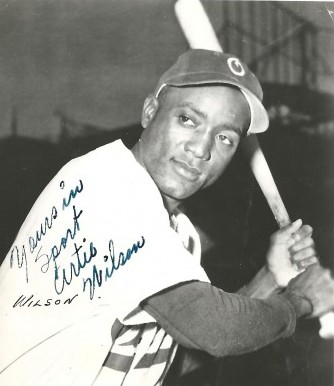

Born Arthur Lee Wilson Oct. 28, 1920 in Springville, AL., Artie taught himself to hit, according to an article published by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, by practicing with a rubber ball and a broomstick.

Later, he wrapped thread around a golf ball and whacked that around. He purchased his first uniform for the grand sum of $2.98 with money he earned as a shoeshine boy.

Artie didnt attend school until he was 16. When he did, it was three days a week. He spent the other two working at the Acipico Pipe Co., where he lost a thumb in an accident. He played semipro ball for the companys entry in the Birmingham Industrial League, which is where he came to the attention of the Birmingham Black Barons.

As a rookie shortstop leading off for Birmingham, Artie hit .346 in his first season and .374 in his second. After slipping to .288 in 1946, he won batting titles in 1947 and 1948 with averages of .370 and .402. That .402 mark in 1948 — 17-year-old teammate Willie Mays hit .262 — makes Wilson, who mentored Mays, the last player in a professional league to bat .400.

“Artie was one of the guys that made sure I didn’t get in any trouble. I owe a lot of debt to him, Mays told The Oregonian long after both retired.

During his time with Birmingham, Wilson was generally regarded as the best shortstop in black baseball. He not only played in four East-West All-Star games (Wilson and Josh Gibson are the only players to have four hits in a Negro League All-Star Game) alongside Hall of Famers Gibson, Satchel Paige, Leon Day, Monte Irvin and Willie Wells, he helped the Black Barons win three pennants in 1943-44 and 1948.

In the mid-1940s, Irvin, not Robinson, reposed at the top of the unofficial list of Negro League players considered most likely to integrate the major leagues. Arties name was also mentioned, along with Arties double-play partner Piper Davis and Sam The Jet Jethroe of the Cleveland Buckeyes. Branch Rickey, after not-so-secretly auditioning a number of black players, selected Robinson in part because of his youth (28 years old), in part because of his charisma and character.

Wilson departed the Negro Leagues after the 1948 season and spent that winter as a player-manager in Mayaguez, Puerto Rico. Then he signed with San Diego of the PCL for 1949, but played just 31 games before moving to Oakland, where, as the franchises first full-time black player, he teamed with future Yankees legend Billy Martin to form one of the leagues best double-play combinations.

“When I got to Oakland, they said they didn’t have a room for me,” Wilson told MLB.com’s Kevin Czerwinski in 2007. “But Billy Martin stepped up and said that he’s got a roommate — I’m his roommate. I got to know Billy quite well.

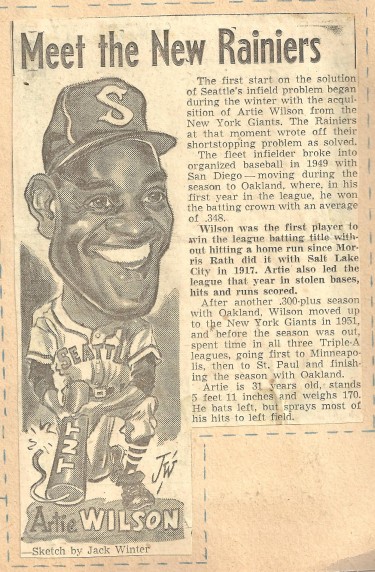

Wilson hit .348 and won the PCL batting title in his first year on the job, also becoming the first to win the batting crown without hitting a home run since Morris Rath did it with Salt Lake City in 1917. Artie also led the league in stolen bases (47), hits (211) and runs scored (129).

After hitting .311 for Oakland in 1950 (264 hits, including 17 triples, in 196 games), Wilson got his shot what there was of it — with the New York Giants in 1951, which ended with Bobby Thomsons Shot Heard Round The World and a National League pennant. Wilson was not there to see it.

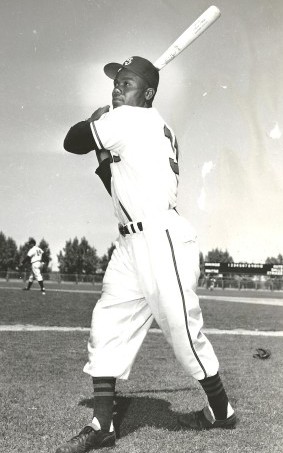

Wilson made his living as a left-handed slap hitter, much like Hillis Layne (1941-’44-45 in the majors, 1947-50 for the Rainiers), who deposited the majority of his hits to left field. While the Giants didnt give Wilson much of a chance, mainly using him as a pinch hitter, New Yorks opponents turned Wilsons batting strength against him by utilizing a shift, as if Wilson was a right-handed pull hitter. Wilson simply could not pull the ball sufficiently to overcome the shift. He batted .182 in 22 at-bats, and when the club called up Mays, they made room on the roster by farming out Wilson.

If anybody could make it, I thought I could make it. If Id gotten with some other club, Id have been the main shortstop, but the Giants had a tough combination: Alvin Dark at short and Eddie Stanky at second, Wilson told the Oregonian after his retirement. Its pretty tough to break into a lineup like that. I was a rookie and didnt know the club, didnt know the players. So I just sat there and waited.”

The chance never came.

“Many observers believed that in the early years of baseball desegregation, an unwritten quota system existed, and so when the Giants brought up Mays, Wilson was farmed out, wrote a Negro League Hall of Fame researcher.

Wilson spent the remainder of 1951 with three teams in the three highest minor leagues (Minneapolis of the American Association, Ottawa of the International League and back to Oakland). Wilson exited the Millers with a bang, collecting an inside-the-park home run, a triple, two singles, a walk and four RBIs in his final game for the club.

All Wilson had to show for his 19-game tenure in the majors was a 1/18th share of the teams World Series pool, which came to $618.88.

While the Giants considered the 31-year-old Wilson slightly past his prime, Earl Sheely, the Rainiers general manager, figured Wilsons hitting and speed would do wonders for his ball club. Sheely made the deal Dec. 10, 1951, and the Rainiers issued a release:

Artie Wilson, Negro infielder, was purchased by the Seattle Rainiers from the New York Giants today, Earl Sheely, Rainier general manager, announced. In exchange, the Rainiers gave the Giants an undisclosed amount of cash and the right to purchase K. Chorlton, outfielder, at the end of next season.

Wilson had played in Seattle as a member of the Oakland Oaks, but his first visit to the Queen City occurred in 1946, when he arrived with the Satchel Paige All-Stars to play the Bob Feller All-Stars as part of a nationwide barnstorming tour (see Wayback Machine: Satchel Paige In Seattle).

In that exhibition, at Sicks Stadium, Wilson started at shortstop on a team that included Paige, 1B Buck ONeill and LF Irvin, and played against a Feller side that included two Seattle natives, LF Jeff Heath of the St. Louis Browns (see Wayback Machine: Jeff Heath, ‘An Oak Of A Bloke’) and RHP Fred Hutchinson of the Detroit Tigers.

Throughout March of 1952, The Times ran a series of Meet The Rainiers portraits on the clubs new players. The one about Wilson conspicuously failed to report that Wilson would become the clubs first African-American player and omitted any mention of his distinguished career in the Negro Leagues, saying, The fleet infielder broke into baseball in 1949 with San Diego.

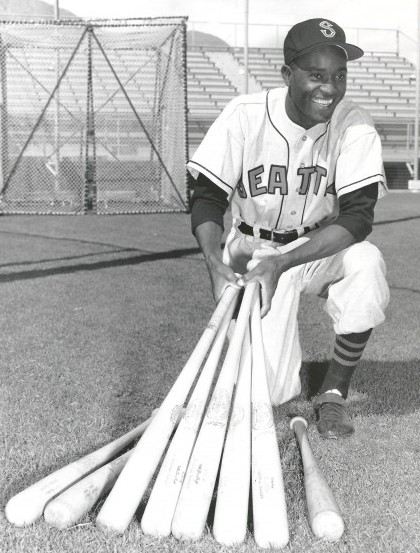

Sheely couldnt have acquired a better pair for the 1952 Rainiers than Wilson and Boyd, who came to the club March 21, 1952, to complete Seattles 1951 sale of Jim Rivera to the Chicago White Sox (see Wayback Machine: Rajah, Rivera, ’51 Rainiers). Boyd arrived in a package that included Rocco Krsnich, who played third base for Seattles 1951 PCL champions, and Rob Wilson, a 23-year-old right-hander.

Wilson and Boyd arrived as former PCL batting and base-stealing champions. Boyd hit .342 for the Sacramento Solons the previous season, finishing second in the batting race to Rivera, who hit .352 before he joined the White Sox. Naturally, Wilson and Boyd became roommates.

Sheely admitted he was entranced by the speed Wilson and Boyd brought to the Rainiers lineup. In fact, the previous season, Boyd and Rivera had faced off in a promotional, 75-yard footrace at Sicks Stadium prior to a Solons-Rainiers game to determine the Coast Leagues fastest human. They met Aug. 16.

The slam-bang rookie from the Bronx (Rivera) beat the fleet Boyd, first baseman of the Solons, by a deep breath, wrote The Times Lenny Anderson.

Wilson and Boyd had much in common. Wilson came from Alabama, Boyd from New Albany, MS. Where Wilson had learned to hit using a rubber ball and a broom, Boyd wrapped crumpled paper with string, threw it in the air and swung at it with a stick.

“I must have done that a million, maybe two million times,” Boyd told The Sporting News.

Like Wilson, Boyd got his start in the Negro Leagues, walking on with the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League in 1947 for $175 per month. Boyd remained in Negro baseball until 1950, never hitting less than .352, and played in two East-West All-Star games. By his final year, he made $500 per month and supplemented his income by selling beer in the off-season.

Also like Wilson, Boyd played his first full year in the high minor leagues in the PCL after departing Negro baseball when he signed with Sacramento for the 1951 season. Where Wilson made minor league stops in San Diego, Oakland, Minneapolis, Ottawa, Seattle, Portland and Tri-City, Boyd traipsed through Colorado Springs, Sacramento, Seattle, Charleston, Toronto, Houston, Oklahoma City, Louisville and San Antonio, as well as Winter League teams in Puerto Rico and Cuba.

I spent a lot more time in the minors than I thought I would or that I wanted to, Boyd told The Sporting News.

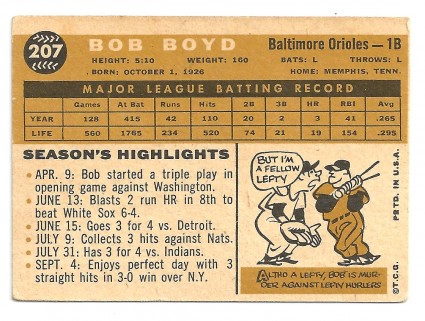

The major difference between Wilson and Boyd was that Boyd managed a 693-game major league career (vs. Wilsons 19 games) with the White Sox (1951, 53-54), Orioles (1956-60), Athletics (1961) and Braves (1961). But he played only three full seasons, his best year coming in 1957, when he finished fourth in the American League behind Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle and Gene Woodling with a .318 batting average. That year he also became the first modern Oriole to bat .300 or better for an entire season (141 games).

After edging the 31-year-old Wilson for the 1952 PCL batting crown, the White Sox signed the 32-year-old Boyd for the 1953 season. Wilson not only received no major league offers, the quota system being what it was, and his throwing arm being what it was, Leo Miller, the Rainiers new general manager (replaced Sheely) offered his 34-year-old shortstop a pay cut. Artie Wilson would have none of it.

I hit .316 last season, second in the league, Wilson told The Post-Intelligencer. Now they are asking me to take a cut in salary. If a player is going to take a cut after hes had a good year, what can he expect if he has a bad year? In baseball you have to make money while youre producing because you certainly wont make it after you quit producing. If I cant get what I want Im going home.

Let him go, Miller told the newspapers. Well have all the infield-hitting punch we need from Bob Boyd, due any day from the White Sox.

Or so Miller thought. He figured Boyd wouldnt stick with the White Sox.

Hardly had those words fallen from Leo’s smiling lips when a Western Union messenger arrived with a telegram announcing that the White Sox were holding on to Boyd with a grip of steel, Anderson wrote.

A swift emissary overtook Wilson at the city limits and steered him back to Rainiers headquarters, where Miller, his confident smile sagging badly, awaited. The next day, Artie was back in uniform, working out.

Wilson, who never had a problem adjusting to the shift used against him by PCL clubs, came to terms on an undisclosed salary for 1953 and batted .332 with 212 hits, including 14 triples, which led the PCL. He returned in 1954 with a .336 average and 222 hits, including 16 triples, which again led the PCL.

Following the season, Rainiers GM Dewey Soriano hired old friend and Rainiers icon Hutchinson (see Wayback Machine: Hutch A Man And An Award) to return to Seattle and manage the club for the 1955 season. Soriano and Hutchinson surveyed their roster and determined a huge housecleaning mandatory.

As purges go, it was a thorough job, Anderson wrote. Some 20 men were exported, including the entire infield, two members of the outfield, half a dozen members of the pitching corps, a spare catcher and the manager himself (Jerry Priddy) walked the plank.

Of all the maneuvers orchestrated by Soriano and Hutchinson in their attempt to rebuild the Rainiers, none surprised the newspapers, or the public, more than the Jan. 15, 1955 trade that sent Artie Wilson to the Portland Beavers, which is why it rated a 72-point headline in The Times.

In addition to the Beavers, three other PCL clubs Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego had approached Soriano about acquiring Wilson. Soriano told Anderson he really didnt want to trade his best hitter, but had an agreement with Hutchinson that if the right deal was offered he would.

It all hinges on the offers these teams come up with, Soriano told Anderson. Wilson has been above .310 in every full season hes been in the league. We will get the kind of players we need in exchange for him or there wont be any deal.

Both Seattle newspapers bannered the deal when it came down.

The Rainiers made their biggest, most daring move of their house-cleaning campaign, wrote Anderson. They traded Artie Wilson. Soriano announced that in exchange for the clubs leading hitter and a top attraction with the fans the Rainiers would get Rocky Krsnich, former Seattle third-base favorite, and Jehosie Heard, a lefty, plus an undisclosed amount of cash (reportedly $5,000). Artie takes with him a .336 batting average, second only to the .348 with which he led the PCL while with Oakland and San Diego in 1949.

Artie was a jack of all trades in the field, but master only at the plate. He played all the infield positions for the Rainiers. As a reason for trading Artie, the club explained that his increasingly weak arm prevented him from playing the kind of shortstop he used to. He could also be a victim of a youth movement. Its also certain that the spectators will miss his enthusiasm and hustle.

Under Hutchinson, the Rainiers captured the 1955 PCL pennant (see Wayback Machine: Hutch & The 1955 Rainiers) with little help from Krsnich and Heard.

Before the first month was out they were on their way to the Texas League and points east, wrote Anderson, evaluating the deal a year later.

Wilson hit .307 in Portland and, by May of 1956, the Rainiers simply had no one who could replace one of the greatest slump-insurance plans in PCL history. So they purchased Wilson from the Beavers when that club went on a youth movement.

Of the 20 men who departed in the purge, only the Wilson deal bounced, opined Anderson. It was a clear defeat for Rainiers management.

The 1956 season became Wilsons last in Seattle. He moved to Sacramento in 1957, and after batting a career-low .263 in 75 games, retired and went to work in a Portland auto dealership. That might have been the end of Artie Wilson as a baseball player, except that he came out of retirement in 1962, determined to give the game one more whirl.

But four years away from baseball proved too much. After hitting .214 in 14 games for Class B Kennewick of the Northwest League, Artie left baseball permanently.

“The PCL was tough,” recalled Wilson in 2007. “We had guys who couldn’t hit .250 or .260 but hit .300 when they were in the major leagues. That’s how tough it was. It wasn’t easy.”

Although he had Alabama roots, Wilson and his wife, Dorothy, settled in Portland after he left baseball. Wilson went to work as an automobile salesman at Gary Worth Lincoln-Mercury in Gladstone, OR., and stayed there, remarkably, until he turned 85 years old.

Quiet, modest, and kind he was a leader in the community and a man who served for years as a role model to many, Dwight Jaynes in The Oregonian wrote after Wilson died. I know all his friends, co-workers and customers at Gary-Worth for decades are better for having known him and will miss him greatly.

“He was a wonderful man known for his soft-spoken manner and ever-present smile. And what a terrific player he was and yes, Im old enough to have seen him play.

I must also say this, I have been blessed in my lifetime to have met several men who played in the old Negro Leagues and to a man have found them delightful people with a twinkle in their eyes whenever they talked about their baseball experience.

They have been an incredibly consistent group to meet and I must say, it must have been a joyful experience to play baseball in those leagues in that time, if those men are any barometer. As much as those players missed by not being allowed in the major leagues, I believe we missed a whole lot more by not being able to see them in that context.

Wilson enjoyed good health up until the end, Bob Boyd not so much. Leaving organized baseball in 1963, a year after Wilson had his 14-game stint in Kennewick, Boyd settled in Wichita, KS., where he became a metro bus driver, in large part so he could continue to play baseball.

The bus company that employed Boyd sponsored a team that competed annually for the national semipro championship. Nicknamed the Dreamliners for the buses they drove, Boyds team featured numerous ex-minor league players as well as a couple of former major leaguers. Boyd played for the Dreamliners for four years.

Diabetes eventually cost Boyd his right leg, but he remained in reasonably good health until 2007, when he died of cancer Sept. 7.

Artie Wilson, the last man to bat .400 in an organized league, the first (by calendar date) to integrate the Seattle Rainiers, a 1988 inductee into the Oregon Hall of Fame, and a 2003 PCL Hall of Fame enshrinee, died Oct. 31, 2010, three days after his 90th birthday. He had Alzheimer’s at the end and had lost a lot of weight.

He just went to sleep one night and didnt get up, said his son, Artie Wilson II.

———————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com