By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Not all important sports operatives scale out at 300 pounds, stand seven feet tall, speak in the third person, are draped in cornrows, or emblazoned with tats. Some toil in the shadows, mere steps from the stars, pitching, promoting and stumping on their behalf, and for the men who lavish cash and booty on them. Bill Sears did this for so long, and for so many, that today he is a better story than all the stories he can tell.

If employed today (he’s retired), Bill would be a “Director of Communications”, possibly a “Media Consultant”, perhaps a VP of something. But when he broke into the sports dodge back in the day such titles didn’t exist.

Rising from one of the lowest social rungs north of the animal kingdom, copy boy at the old Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Bill became a simple “Publicity Director”, charged with delivering news and images to Seattle media and fans meant to inform, entertain and burnish the profiles of the owners, teams and athletes he served.

There is knowing history, and there is living it. For 50-odd years, beginning in the late 1940s, Bill engaged in relentless tub thumping on behalf of Seattle and its teams, running through enough gigs to stupefy the Kardashian sisters: Seattle Rainiers (1954-57), Seattle University (1957-63), Seattle Angels (1964-68), Seattle Pilots (1969) and Milwaukee Brewers (1970) — and that’s just a resume starter.

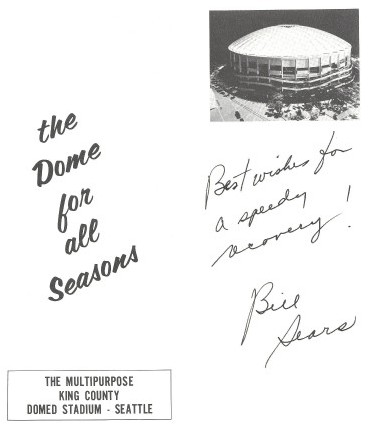

He almost became the first publicity director for the Seahawks (1976), opting instead for a tour of duty with the King County Convention and Visitor’s Bureau. That led to a long run as Directory of Publicity for the Kingdome. Yes, there’s more.

Bill helped promote the 1962 and 1974 World Fairs in Seattle and Spokane. He served on the organizing committee that netted Seattle three NCAA Final Fours (1984, 1989, 1995). Working with the same committee, he and his fellow organizers nearly convinced (in 1988) the NFL to award the 1992 Super Bowl to Seattle. Simultaneously, he was in the thick of the action that resulted in Seattle hosting the 1990 Goodwill Games.

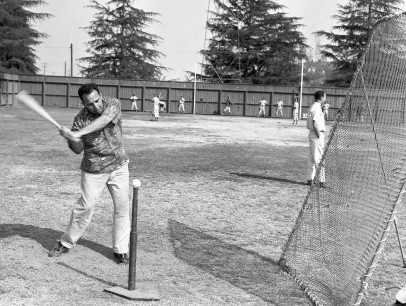

A summary of each aforementioned task could run to pages, but we glean this: Bill knew a Seattle without a Space Needle and an I-5, and minus an Alaskan Way Viaduct. He even knew Seattle before Dick’s Drive-In became a landmark. He knows first hand what it is to watch Hugh McElhenny run, Ewell Blackwell pitch, Fred Hutchinson manage, Elgin Baylor soar, and Guyle Fielder skate. Oddly, Bill even has an intimate understanding of what it is like to play baseball with Maury Wills.

Talk about enduring: Bill grew up watching baseball at old Civic Field (current site of Memorial Stadium), cheering on the likes of Mike “Mother” Hunt and the Seattle Indians. He later saw both Sicks’ Stadium and the Kingdome, two venues in which he spent much of his life, come and go.

As a young man, Bill dropped out of Queen Anne High after the start of World War II and joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, flying more than 30 bombing missions over Europe. Honorably discharged on Oct. 8, 1945, he returned to Seattle and, using the G.I. bill, buried his local roots this deep:

He attended the University of Washington (briefly) and Seattle University, working at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer (copy boy) and The Seattle Times (reporter) to make ends meet. While at the P-I, Bill had a chance to mingle with the likes of heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano and UW football star Hugh McElhenny, trysts set up by P-I sports editor Royal Brougham.

“The P-I sponsored the Gold Gloves (boxing) in those days and Brougham would always bring some famous guy out to referee the main match. He brought Jack Dempsey a couple of times, and Rocky Marciano once. I got my picture taken with him. That’s how that happened.

“Also when I worked at the P-I, Brougham told me to deliver an envelope to McElhenny. He told me where he lived. I went there and he answered the door. I knew he was good. I looked kind of open-mouthed at him.”

Another P-I employee, columnist Emmett Watson, who caught Fred Hutchinson at Franklin High School, helped Bill land his first sports job in 1954 with the Rainiers. For the next next three years, Bill promoted the club through the managerial tenures of Jerry Priddy (1954), Fred Hutchinson (1955), Luke Sewell/Bill Brenner (1956) and Lefty O’Doul (1957).

In 1956 and 1957, the Rainiers took junkets to Alaska to play exhibition games against local semi-pro teams. “Rainier Brewery owned the team (Rainiers) and it did a lot of business in Alaska — sold a lot of beer there,” said Sears. “We went up first when Luke Sewell managed and the next year when Lefty O’Doul managed.

“The second year, we were short on players and the team had to use me to fill in. I played right field. Maury Wills was a rookie shortstop for us, but we had him at second base for this game. Bill Glynn was playing first with Maury at second. One of their guys hit a short fly into right and I came in to make a play on the ball. All of a sudden, Glynn runs out and he’s yelling for it. Wills comes out there and he’s not yelling, and I stopped. So did Glynn, and the ball dropped between us. Wills says to me, ‘You see what we have to put up with?'”

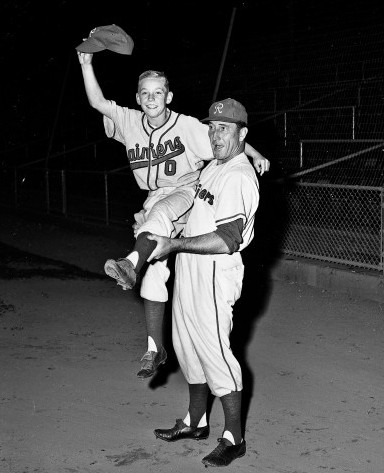

This is the essence of a crack publicity man: With the 1955 Rainiers on the brink of a Pacific Coast League pennant, and the P-I and Times in need of a celebration photograph on an impossible late-night publishing deadline, Sears posed manager Fred Hutchinson and a Rainiers batboy in a victory clutch — the day before the team actually clinched the pennant.

Beginning in the mid-1940s, if it happened in Seattle, Jack Gordon made certain his name was plastered all over it. An unrivaled schmoozer, Gordon owned a small public relations firm that handled a variety of assignments for Greater Seattle Inc., an entity formed by the city’s exalted (including Gordon himself) to promote Seattle to its own citizens and the rest of the country.

Greater Seattle Inc. organized Seafair, the hydroplane races and other civic amusements, and brought professional football, basketball and bowling (then a big deal) exhibitions and tournaments to the city to demonstrate its big league merits, one reason why the Seahawks, Mariners, Sonics (for 41 years) and Sounders exist today.

Greater Seattle Inc. also flooded the town with entertainment celebs, including Bob Hope, Bert Parks, John Raitt, Gisele Mackenzie, Martha Wright, Pamela Britton and others to perform in the Green Lake Aqua Theatre, the construction of which is attributable to Greater Seattle, Inc.

After Bill arrived at spring training with the 1957 Rainiers, he received a call from Gordon, then doing publicity work on behalf of the Seattle U. basketball team. Up to his neck in unrelated matters, Gordon asked Bill to pinch hit for him and accompany the Chieftains to the National Invitational Tournament in New York City and crank out some p.r. copy on their behalf.

“Ultimately, that’s how I got into the public relations,” said Bill. “Jack Gordon became my mentor.”

After working the NIT, Bill left the Rainiers and joined the Chieftains full time, and just in time to witness the greatest season in the school’s basketball history, the 1958 Elgin Baylor-led run that ended with the Chieftains playing Kentucky (lost) for the NCAA championship. Seattle U. coach John Castellani became so distraught over the defeat that he refused to leave the team’s locker room following the final buzzer, instead dispatching Bill to the court to accept the national runner-up trophy. That’s not even his most memorable Seattle U. basketball memory.

Earlier in the 1958 NCAA Tournament, the Chieftains found themselves in San Francisco to play the heavily favored Dons in a second-round game. Bill set up a press room, replete with open bar, at the Sir Francis Drake Hotel for sports writers to use after the contest. Following Seattle U.’s 69-67 victory, a Seattle Times reporter availed himself of the open bar to such an extent he couldn’t file his game story.

“The Times guy was blotto, passed out,” recalled Bill. “I turned to Boyd Smith (the Seattle P-I reporter) and said, ‘I don’t think he’s filed his story. He hasn’t even got his typewriter out.’ Smith says to me, ‘I think he’s in trouble.’ So I say to Boyd, ‘Let me use your typewriter.'”

The consummate p.r. man, Bill cranked out a story on Seattle U.’s victory — he wrote it under the sloshed scrivener’s byline — and took it to Western Union, which sent it to the Times, the usual transmission procedure in the decades before e-mail and Twitter. This might have been the only time when a P-I typewriter was used to produce a story that appeared in the Times.

Bill remained at Seattle University through 1963, when he created headlines in both Seattle newspapers by quitting after Vince Cazzetta (John Castellani’s successor) was forced out as head coach, in part due to bad blood with athletic director Eddie O’Brien.

“I really liked Vince,” Bill said. “So when he left, and because of my respect for him, I followed suit. There was quite a to-do about that. And that ended my career at Seattle University.”

Bill didn’t remain in idle long. To his good fortune, Seattle Rainiers icon Edo Vanni, a life-long friend, had been hired as general manager of the Seattle Angels (the Rainiers had been sold to the Boston Red Sox in 1960; the Red Sox, in turn, sold the club to the Los Angeles Angels in 1965).

“Edo wanted some help with publicity for the club so he talked me into going to work for the baseball team,” said Bill.

Life is not so much one thing after another as it is one thing during another. Coinciding with the years in which he worked at Seattle U., and before he transitioned back to baseball, Bill continued to accept public relations assignments from Gordon, accounting for his involvement with Seafair and the 1962 World’s Fair (and later the 1974 World’s Fair). But by 1965, baseball had become his daily routine, and he ran with it until the American League awarded Seattle a franchise — the 1969 Pilots. Naturally, Bill became their first (and last) public relations director. And, no, he never had a clue that season that Pilots’ reliever Jim Bouton was taking notes for a book that would become Ball Four.

“I never heard anybody mention it,” said Bill. “When the book came out it was quite a surprise. I’ll say this: Bouton is no dummy. He’s very perceptive, a very smart guy. What I remember most about him is that I had a secretary named Sharon. She was a real knockout. Bouton was always hanging around, and I told him that I could hardly get any work done with ‘you bugging Sharon’. But he was a good guy.”

“Ball Four” became one of two “unforgettables” to emerge from the Pilots’ only season. The other: When 1B/OF Mike Hegan was asked, “What’s the most difficult thing about playing Major League Baseball?”, he famously quipped, “Explaining to your wife why she needs a penicillin shot for your infection. ”

“It’s still true,” said Sears, who followed the Pilots to Milwaukee after their single bankrupt season in Seattle (he managed to glom onto Tommy Harper’s spring training jersey, which he still has).

But the Milwaukee job lasted only a year — he submitted his resignation to Brewers owner Bud Selig, who wasn’t pleased — and Bill soon found himself back in Seattle, laboring for the Convention and Visitor’s Bureau, where he oversaw, among other duties, the distribution of news releases relating to the construction progress (or lack of it) of the Kingdome, due to open in 1975.

By the time of the Dome’s actual opening — 1976 — Bill had two choices: become publicity director of the expansion Seattle Seahawks, or take a job at the Kingdome. Having already devoted some years to the concrete cavern, he chose the Dome.

Then, after King County hired Ted Bowsfield to serve as Kingdome director, Bill and Bowsfield began plotting ways to bring marquee events to the building. They landed on the idea of bidding for the Final Four, an event Seattle had not hosted since 1952, when it was held at the University of Washington.

The bid they developed so impressed the NCAA — Bill helped make the presentation in Colorado Springs — that it awarded the 1984 Final Four to the Kingdome. Final Four Weekend went so well that the NCAA awarded Seattle two more Final Fours (1989, 1995) as a result.

A subsequent effort to land the Super Bowl didn’t go as well, no fault of the Seattle Bid Committee. Bill, John Nordstrom, Gene Pfeifer, Ted Bowsfield and Bob Walsh (the committee) had spent six years on the project and been orally assured of landing the 1992 game by NFL Commisioner Pete Rozelle after a formal presentation to the Super Bowl Site Selection Committee that included actor John Housemann, the taciturn law professor of The Paper Chase TV series, extolling Seattle’s virtues on video.

But two problems torpedoed the effort. The Nordstrom family sold the Seahawks to Ken Behring, a California real estate developer, who quickly alienated most NFL owners (most plainly loathed the guy).

Then, King County Executive Tim Hill and Chamber of Commerce President George Duff absurdly formed a second Seattle Bid Committee, blatantly designed to usurp the work of the original. The NFL did not look favorably on the contrived consortium. But rather than sort out which bid committee was the “official one”, the NFL simply awarded the 1992 Super Bowl to Minneapolis (and that’s why Seattle has never hosted a Super Bowl).

The loss of the Super Bowl still sticks in Bill’s craw, but on balance the career he carved was mostly a five thumbs-up performance, due to the people he encountered, the games he saw, the athletes and officials he came to know, and the writers with whom he worked, and often bailed out. High on Bill’s list of most memorable characters: Royal Brougham and Emmett Watson.

“Royal was very good to me, a very nice man,” said Bill. “A lot of people didn’t like him. He was kind of holier than thou — and he could cut your heart out, as many coaches found out — but he was a great human being.

“He did a lot of things people didn’t know about, works of public mercey. When I worked at the P-I, every once in a while you’d see him with some raggedy tag guy. He’d befriend a bum and give him money.

“When you got to know Royal and saw the good side of him, he was something. At one point, I came down with testicular cancer. I was living in north Greenwood then, laying in bed. There’s a knock at the door and here was Brougham. I was stunned, Mr. Big took the time to sit by my bed and talk with me. It was a very moving.

“Emmett Watson was a great friend. He could be a very difficult person to get to know, partially because of his hearing problems. He was self-conscious about that. He was one of my mentors. If I’d get out of line, he’d call me up and give me hell.”

Leo Lassen, writer and broadcaster, remains one of Seattle’s iconic baseball figures, and an announcer so gifted he could explain the infield-fly rule so that anyone could understand it. “He was a very unique guy,” Bill said. “I got to like him real well. He’d come down to the press room after games, and he loved his beer. He was literally Mr. Baseball in Seattle and had as big a following as you can have. He was the Dave Niehaus of his time, although Leo didn’t have Dave’s personality. But growing up around here, if you had any interest in baseball you spent a lot of nights with Leo Lassen. My grandfather was Leo’s biggest fan. He’s part of the memorabilia of Seattle sports.”

When Lassen developed lung problems that eventually led to his death, Bill Sears reached out, despite the fact that Lassen had become a virtual recluse in the final decade of his life.

High — if not highest — on Bill’s list of most memorable athletes: Elgin Baylor.

“I had as good as a rapport with Elgin as someone like me could have had,” said Bill. “If he said 10 words it was surprising. He was very quite, very reserved, with outsiders and newspaper guys. His actions spoke for him.

“Baylor was probably the most impressive athlete I’ve ever seen. I remember games . . . he’d pass to a guy and hit him in the head. The guy was looking and didn’t see it. He had a complete command of the floor, and he’d see everything. He was as good a playmaker as he was a shooter.”

Given that Bill spent 50-some years promoting Seattle with creativity and elan, while also enduring sport writers without losing his sense of humor, the question we have is, Why isn’t this guy a member of the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame?

——————————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi, who writes The Wayback Machine every Tuesday. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at the following e-mail address: seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

(Wayback Machine is published every Tuesday as part of Sportspress Northwests package of home-page features collectively titled, The Rotation.)

27 Comments

Enjoyed the article. Always happy to read about the people in the background who make baseball great year after year!

It was great to see Mike Cameron sign that one-year deal to retire as a Mariner, and especially to see 46,000 people rising as one to give Cammy his ovation. Mike came into a very difficult situation as a replacement for a Hall of Fame centerfielder (and Ken Grouchy Junior should go in the first year he’s eligible), but Cammy certainly made the most of it.

And, by the way, Cameron wasn’t a dropoff from Grouchy at the plate in terms of genuine production. Look at the side-by-side batting stats Cammy and Grouchy had between 2000 and 2003 for the four years Mike was in Seattle while Grouchy was in Cincy:

CAMERON: 554 H, 115 2B, 19 3B, 87 HR, 353 R, 344 RBI, 106 SB, .256 BA

GROUCHY: 338 H, 62 2B, 6 3B, 83 HR, 208 R, 232 RBI, 10 SB, .271 BA

I willingly concede that Grouchy missed a LOT more games than Cammy did in that period, but the numbers are what they are. Who genuinely produced more for their team during those four seasons? Or, to put it another way, would the Mariners have been better served by an injury-prone player beginning his career decline who obviously didn’t want to play for them, or a player who missed just 38 games in four years at the peak of his career who was glad to be in Seattle?

I think this ended up being a great deal for the Mariners, given both the circumstances leading to the trade and how things went for each player during the four years after it.

Here’s a little test for you, Art: Did the M’s draw 46,000 last night because Felix was pitching? Or because it was the Home Opener, and they would have drawn 46,000 no matter who was pitching?

Remember, at the Kingdome, the M’s started almost every season at home, because they were indoors, and Randy Johnson started every M’s home opener, which always sold out. That is why Randy always drew a few more fans than the other M’s starters at home — because Randy always started the home opener.

So, what do you say? Did Felix draw 46,000 fans last night, or did the Home Opener draw 46,000?

By the way, I went down to Lander St. last night, just to see how the train crossing affected traffic in the area before the M’s home opener. I watched it from 5:30 to 7:00, and there were 10 trains which crossed Lander during those 90 minutes — an average of one train every 9 minutes.

There were 3 Sounder trains, each of which had 7 cars, and each of which blocked traffic for just one minute.

There were 2 Amtrak trains, each of which had 11 passenger cars, and each of which blocked traffic for about 1.5 minutes.

There were 4 BNSF trains. One had just 4 engines, and 0 cars, and took one minute. One was just a single engine and took about 45 seconds to cross. One had 5 cars and took 2 minutes to cross. And one had 23 cars and took about 3 minutes to cross.

And there was one Union Pacific train, which had 100 cars and took about 5.5 minutes to cross.

All, in all, these trains had almost zero effect on traffic. All except the Union Pacific 100-car train were not much worse than waiting for a normal red light at an intersection. Traffic never got backed up far from the RR crossing except for that long UP train.

An overpass on Lander over the RR tracks would not make much difference whatsoever to traffic to M’s games. Last night drew 46,000 (which is why I wanted to see the traffic down there last night) and I did not see any signs of any significant traffic problems on Lander St between 5:30 and 7:00 at all.

Always nice to see the UW schedule non-league games against schools NOT named Houston Baptist, New Jersey Tech or Florida Atlantic. And AWAY from the safe environs of Hec Ed, no less.

Not that Mark Few is holding his breath waiting for a UW-Gonzaga rematch anytime soon. There’s no embarrassment for the UW to lose a road game at UConn. Losing to the Zags has been something else.

Mixed emotions on this one. My son and I are both Husky fans but my son is also a WWU grad. National and world championships are few and far between in this part of the world, so we’re sad to see him leave Bellingham. At least he stayed close to home. Maybe he can help do the same at UW.

“The only problem is that the guy on the field in charge has never faced a pro defense that is loaded with talent and enlightened by a pro scouting report on him.”

And his backup has only done so twice.

Interesting times.

That’s what life is like in the land of the outlier, Jamo. Carroll is a risk-taker, but if you listen carefully, his primary mantra on offensive is control of the ball — no turnovers, and run the ball as often as possible. That’s how he sees Wilson surviving, and succeeding, as a rookie QB.

Wilson is smarter than TJack on every down, not just third.

But one’s bones are made on third. And if you’re right about first and second down, then there’s a lot of third-and-one. Everyone looks smarter on third-and-one.

I believe Ken Whisenhunt was OC (offensive coordinator) not DC for Pittsburgh. Dick LeBeau is the longtime defensive coach. And before being the OC, Whisenhunt was the TE coach. I don’t see any coaching prior to being a head coach (in the NFL) that was on the defensive side.

Good catch, E-man. Fixed. Thanks.

Andy, I believe I confined my write-off to the first game, not the season. My point was he’s going to see things he’s never seen Sunday, and fans need to temper expectations for the first game. Growing pains, y’know?

That’s OK, Trakar. I have faith in you as a reader.

Telling everyone that Russell Wilson will see things he’s never seen before makes zero sense to me. Sure, the kid hasn’t played an NFL game yet, but I would think that he has seen a lot of different looks in practice from a very good defense. It wouldn’t make sense for Seattle coaching to only throw a vanilla defense at him in practice. That wouldn’t do the team or Russell any good. Russell Wilson will be prepared to handle everything that the cardinals can throw at him. It seems as though people forget that there is more to preparation than just preseason games.

This may the first time in the history of the Seahawks that our first string qb and 2nd string qb are so close in talent that if one goes down we can still win. Flynn is a very good qb as well.

That’s a key point in why Carroll feels the risks have been minimized in starting a rookie.

I’m with you. How can you not love a kid who’s so confident and poised at such a young age? When the Seahawks drafted him, I thought he’d earn a roster spot based on what he’d done on and off the field at Wisconsin, but starting the first game as a rookie? Didn’t see that coming, but PC means what he says about competing and Wilson was born to compete, lead and win.

My guess is that if PC is willing to stick with Russ through any growing pains, he’ll develop into a solid NFL quarterback. He’s already showing he can lead a decent pro football team as a 23-year-old rookie, and that’s pretty awesome in itself. Having a run-oriented offense will help because it takes pressure off him.

I think Sunday is going to be a hard one, but that’s OK. You start a rookie, you include his learning curve. Carroll would not do this if he didn’t understand the inevitable shortfalls. The key is making them as short as possible.

Well said, David. One thing to add to the likes: He has a fine sense of knowing the difference between running because he should and running because he can. That’s one up on Michael Vick.

One to add to the apprehensions: Despite the intensity of his practice time, Wilson is a long way from knowing his receivers’ open-field decision-making. Best example, Hasselbeck to D-Jack, Hasselbeck to Ingram. Function of time, not ability.

You’re a fine man, Tim.. Please tell your friends about SPNW!

Pixel, sounds like you remember McGwire, Gelbaugh, Mirer, Stouffer, etc. Do yourself a favor and put the nightmare to bed.

Tomoreow will be interesting.

I’m probably being redundant by now (what’s new?), but I’m of the mind that Wilson’s learning curve may be as off-the-charts as his leadership skills…whatever mistakes he makes during the first three games will be gone by the fourth because he may be the one player who’ll spend more time watching film than his coaches.

Maybe it’s a poor analogy, but while so many people were awed by Mike Tyson’s overwhelming physical power, he made all that strength work for him because he was a devoted student of boxing. Wilson isn’t as dominant in an athletic sense, but he’s a dedicated student of football whose only goal is to keep getting better and better. I think Vince Lombardi would’ve loved coaching this kid.

Matt Flynn must be feeling like Wally Pipp right now, except at least Wally was an established starter before Lou Gehrig “filled in” for a day.

Scusa me. I did mean both were competivitve and close to equal. And to think I used to wriote for a paper.

Really thought the Sounders outplayed Portland here, just couldn’t get the ball in the net.