By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

John Pinnell (sometimes spelled Pennell), a second-generation settler in Seattle, Washington Territory, oversaw two significant business projects after he arrived from San Francisco sometime in 1861. Neither enterprise won the interloper universal acclaim among residents of the region.

Shortly after decamping in what was then a crude logging town, Pinnell met with local authorities and convinced them to approve the towns first bordello in exchange for an annual $1,200 licensing fee and assurances that he would keep his business activity confined to a district south of Mill Street, now Yesler Way.

According to Those Naughty Ladies of the Old Northwest (published in 1990), a collection of stories and anecdotes about the regions colorful madams of the past, Pinnell constructed a large, rectangular building that housed a dance floor, a bar, and a number of private rooms where the primary business would be conducted.

Pinnell called his establishment Illahee, a Chinook jargon word meaning a home away from home, and staffed it initially with young women from local Indian tribes (Pinnell traded food and other goods for their services). Later, as Illahee surged into profitability, Pinnell recruited unemployed dancehall girls from San Franciscos Barbary Coast to work the string of establishments he added to Illahee.

The area around Illahee came to be known as Skid Row (San Francisco had a similar district, “Tenderloin”) and soon evolved into one of the countrys largest concentrations of unregulated vice — bawdy houses, breweries, saloons and gambling (at one time 24 saloons operated 24 hours per day). The Skid Row district served as a magnet for lumberjacks, sailors and especially Alaskan miners laden with gold from the Yukon.

Having introduced Seattle to the commercial sex industry, and becoming (in some quarters) a respected businessman in the process, Pinnell in 1869 introduced it to organized, if irregularly contested, horse races at his new facility, the Seattle Race Course. Along with the track came more brothels and saloons, and more money for Pinnell.

The Seattle Race Course shut down in 1878, reopened in 1883 as the Seattle Driving Park, and remained active until 1892, when it shuttered again.

In 1902, in an effort to better utilize valuable downtown real estate and distance respectable Seattle citizens from what The Seattle Times described as the citys biggest cesspool, city officials ordered that the Skid Row area be moved several blocks south. That same year, the King County Fair Association constructed The Meadows Race Track at the south end of Beacon Hill and the Duwamish River (the track was surrounded on three sides by loops in the Duwamish).

The one-mile dirt oval included an opulent clubhouse, a grandstand that accommodated 10,000, and a series of stables that provided stalls for 1,000 horses. According to The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, bookmakers paid $150 a day to The Meadows in exchange for the privilege of taking bets out of 150 stalls constructed especially for that purpose.

The first racing season in 1902 lasted 10 days. But beginning in 1903, the King County Fair Association extended it to 30 due to popular demand, which grew due to the proximity of the Seattle Electric Companys interurban rail line that carried betting men from First Avenue South and King Street to the track in cattle cars like livestock to a rendering.

The first automobile race in the area took place at The Meadows in 1905. Bill Boeing witnessed his first airplane demonstration (and first airplane crash) from the grandstands of The Meadows. Boeing also built his first airplane on the site.

But while the track served as an important entertainment venue, a gaggle of what one newspaper labeled temperance terrors, began assaulting political officials, demanding that they crack down on the nefarious aspects of the neighborhood. They aimed to limit saloon licenses, disperse the red-light district, and eliminate the tracks bookmakers.

As The Argus (a weekly Seattle newspaper published between 1894-1983) described The Meadows in 1908: It is the worst gambling hole that has ever been opened . . . Men lose all their money at the races, and women lose their men.

One do-gooder, a former Ohioan named Edward H. Cherrington, chairman of Seattle’s Anti-Saloon League, helped convinced the state legislature to crack down on Skid Row blight. Although Cherrington specifically wanted to stamp out of existence every booze joint in the territory, he got more than he wanted.

In 1908, in a fit of moral fervor, the legislature banned gambling statewide, forcing The Meadows out of the thoroughbred racing business.

(Although thoroughbred racing ceased, the grounds served Seattle in other ways for a number of years. Seattles first powered airplane flight took place there in 1910. On May 29, 1912, Seattles first airplane fatality also occurred there when pilot J. Clifford Turpin fell out of the air and hit the grandstand, killing one and injuring 14. The Meadows was paved over in 1928 to createBoeing Field.)

Had it not been for the 1929 stock market crash, thoroughbred racing might never have returned to the state, or at least returned when it did. Starting in 1922, a pair of Seattle real estate entrepreneurs, Joseph Gottstein and William Edris, embarked on a campaign to revive the sport.

Despite their best efforts, they got nowhere until after Oct. 28-29, 1929, when the collapse of U.S. financial markets triggered the Great Depression, which severely impacted the states ability to generate revenue.

With lobbying support from future U.S. Sen. Warren G. Magnuson, then a state representative, Gottstein and Edris enlisted another state representative, Joseph B. Roberts, to introduce House Bill 59, a measure that, if passed, would legalize pari-mutuel wagering on horse races and guarantee that a five percent tax on the gross handle (total money wagered) would end up in the states coffers.

Vinson Joseph Gottstein, 18 years old when The Meadows shut down in 1909, was born in Seattle on July 14, 1891, in the family home at Ninth Avenue and Columbia Street. His father, Meyer (Mike), had emigrated from Russia and his mother, Rosa, from Poland.

Upon arriving in the U.S., Meyer headed west and made his living (and a very good one) as a whiskey wholesaler in North Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming before landing in Seattle in 1879. There, Meyer launched the M. Gottstein Investment Co., which, in the years following Prohibition, concerned itself with mortgage loans, real estate and insurance.

Rather than matriculate to the University of Washington, Joe Gottstein, went east and attended New Hampshires Phillips Exeter Academy. Then he enrolled first at Princeton University and later at Lafayette before moving on to Brown, where he played on the offensive line for the Bears 1912 football team.

Gottstein also wrestled and had a passion for the horses, frequently attending races in New York his initial enthusiasm for the sport stemming from the fact that his father had been an investor in The Meadows, often took Joe there, and presented him with his first thoroughbred when Joe turned eight years old (Prince Liege).

After completing college, Gottstein returned to Seattle and, by 1919, had become president of Gottsteins Inc. He bought and sold real estate successfully and became involved in a variety of civic concerns. Most notably, Gottstein joined a group that built Seattles Coliseum Theater, at the time considered the finest in the world.

Gottstein couldnt help but come to know and do business with — Edris. A newspaper article, dated Oct. 28, 1926, reported that, Two young Seattle businessmen, William Edris and Joseph Gottsbein, have taken a considerable part of downtown Seattle in their capable hands during the past couple of years and have been changing the entire aspect of the citys business center.

Once, when it was suggested that Gottstein seemed to own half of downtown Seattle and had his eye on the other half, Gottstein remarked, Why, the town just cant keep from going ahead, can it? Well, somebodys going to make money on these big deals. Too many cities wait for outside capital to come in and clean up all the gravy.

Weve got confidence in Seattles future, and there isnt anything else to it except buy ’em an sell ’em. If Seattle money doesnt develop Seattle, somebody elses money will. Ill invest mine right here.

Born in Eugene, OR., Edris graduated with a law degree from the University of Washington in 1922, the same year he and Gottstein launched their quest to return thoroughbred racing and betting to Washington.

While Edris shared Gottsteins love of thoroughbred racing, he wasnt nearly as personally invested in it as his partner. Real estate most fascinated Edris, who went on to acquire an impressive array of properties, including the Olympic and Roosevelt hotels in Seattle, the Davenport Hotel in Spokane, the Fourth and Pike Building in Seattle and the Pioneer Security Co., which operated theaters in Seattle (Liberty and Venetian), Tacoma (Roxy), Enumclaw and Great Falls, MT.

Pioneer Security Co. also owned and operated the Broadway Market and Vons Restaurant, and Edris had personal financial stakes in the Seattle Rainiers, Seattle Hockey Club and Sound Bridge and Dredging.

Gottsteins determination to return thoroughbred racing to the area received detailed treatment in an excellent series of articles, many by Susan van Dyke, about the inaugural class of Washington Racing Hall of Fame inductees in 2003.

Wrote van Dyke: By 1922, racing (except for amateur races at county fairs) had lain dormant for 14 years in the Evergreen State. Gottstein and Roscoe Drumheller got together in the hopes of legalizing racing again. With the help of a young Seattle lawyer named Edwin J. Brown, whose father was then mayor of Seattle, a racing bill was submitted to the legislature. The vote in the Senate resulted in a tie, with the lieutenant governor, Wee Coyle (a former University of Washington quarterback under Gil Dobie), casting the tiebreaker in racings favor.

Unfortunately, the bill failed to reach the floor in the House of Representatives . . . Gottstein never gave up the battle.

Following the stock market crash, the state found itself strapped for cash and ready to seize upon any source of revenue. The time for thoroughbred racings return had come and, on March 20, 1933, Gov. Clarence D. Martin (Washington States football stadium is named after him) signed House Bill 59.

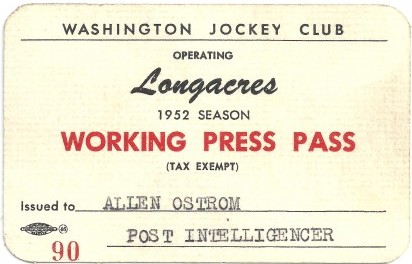

Gottstein wasted no time reviving the sport of kings. He founded the Washington Jockey Club on June 20, 1933, after receiving a state permit to own and operate a one-mile dirt track. Newly formed, the Washington Horse Racing Commission awarded a 40-day meet (Aug. 3-Sept. 17, 1933) to a new racing partnership headed by Gottstein and Edris.

The Washington Jockey Club then foundl 100 acres of land near the Renton Junction, purchasing the property from a dairyman named James Nelson. The Jockey Club, according to van Dyke, selected the property (once a potato farm) for three reasons: The fine alluvial soil was well scoured by glaciers in past ages; no danger of rocks. This made a safe running track with much less work than in many locations. It was close to railroad siding, which was important in the beginning. It was removed from the city and easily accessible, both from East and West Valley highways.

What happened next would seem a ludicrous impossibility today. Under Gottsteins direction, a throng of workers, estimated at nearly 3,000, erected a functioning thoroughbred racing track in just 28 days.

Gottstein accomplished this feat in part because the ground that the Washington Jockey Club selected was fairly level, but mostly because of the Depression climate: Gottstein never lacked for labor because everyone wanted to work in those days.

Gottsteins crews labored around the clock, and he often toiled along with them. As workers plowed the grounds, an acquaintance of Gottsteins, the renowned architect, B. Marcus Priteca, penciled out the overall design of the new facility.

Born in Scotland and educated at George Watson College, Priteca arrived in Seattle sometime around 1914. By the time he began his design of Gottsteins race track, Priteca had numerous architectural successes: The Pantages Theater (1911), the Crystal Pool and Natatorium (1913, where swimming coach Ray Daughters transformed Seattle teenager Helene Madison into a triple Olympic gold medalist), Coliseum Theater (1916), Capitol Theater (1920) and Orpheum Theater (1927), among them (Priteca designed numerous theaters because he was a whiz at acoustics).

Pritecas design called for a grandstand and clubhouse, a dirt oval racing surface and an allotment of horse stalls, which called for two million board feet of lumber. The track was ready to go on Aug. 3, 1933, when Gottstein, Edris and Priteca rose to greet a clear day and what would, over the years, become a typically fast track.

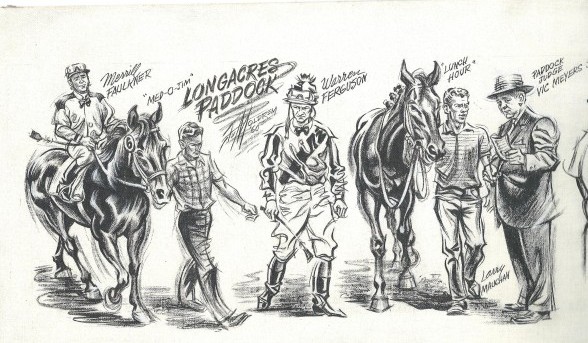

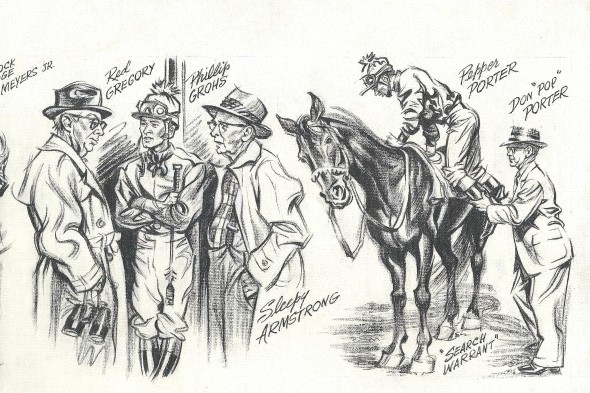

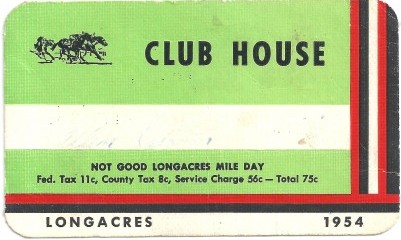

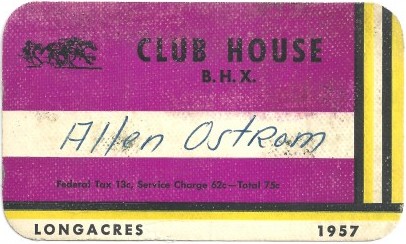

More than 11,000 people coughed up $1.10 in admission to enter the new facility (named Longacres by Gottstein in a salute to Frances famed Longchamps, which Gottstein had seen as a boy), and pumped $13,000 through the mutual wickets. Neither Gottstein nor Edris would live nearly long enough to witness the tracks remarkable 59-year run.

As van Dyke pointed out in her superb 2003 series, Longacres became one of the West Coasts (and nations) most progressive thoroughbred tracks (to say nothing of its splendid ambience).

Longacres became the first track of its size to install a totalizer (a machine used for posting odds and results) and photo-chart camera. It was the first to carry an insurance program for jockeys and exercise boys, the first to license a female trainer (Ruth Parton), the first to introduce Sunday racing, the first to license a Japanese rider, the first to introduce the electric starting gate.

For all of that, Gottsteins most enduring legacy remains the regional sporting tradition which he created and introduced to Northwest racing fans two years after the track opened, in 1935.

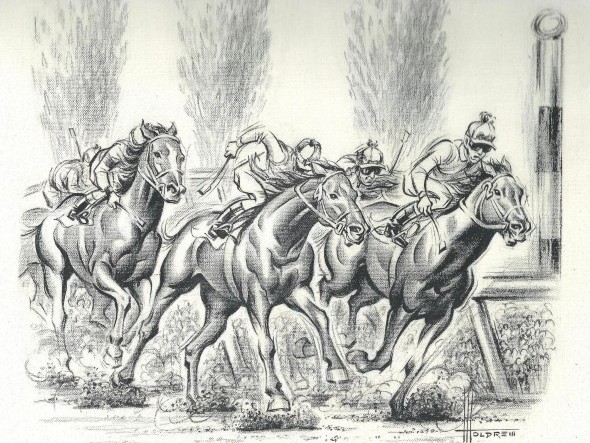

That year, sensing the need for the dramatic and desiring to lure better horses and jockeys to the Northwest, Gottstein established the regions most important thoroughbred race, which came to be known as the Longacres Mile.

Gottstein selected the mile distance precisely because it was not considered a classic distance. Gottstein knew it would take a special horse to excel at a mile because it split the difference between a sprinter and a router: One mile was too long for a sprinter but not long enough for a router (distance horse).

The initial purse of $10,000 came directly from Gottsteins personal checking account. It was an unheard-of sum deep in the Depression. Consider that the purse stood for four decades as the largest for a one-mile race.

The first Longacres Mile attracted 16 runners and a packed grandstand. Coldwater, dismissed by the bettors, defeated the favored Biff, a grandson of Man o War carrying 16 more pounds, winning by a neck. Over the years, no fewer than 13 Hall of Fame jockeys, including Eddie Arcaro (Two and Twenty, 1950), Bill Hartack (Quality Qwest, 1955), Johnny Longden (Harpie, 1962), Bill Shoemaker (Bad ‘n Big, 1978) and Gary Stevens (Louis Cyphre, 1991), competed in the Mile.

Edris cashed out his stake in Longacres in 1937 and devoted the remainder of his business career to his real estate holdings. He died at age 76 in November of 1974 of a lung-related problem in Palm Springs, CA.

Despite his important real estate holdings in downtown Seattle, not one of Edris obituaries merited more than 10 inches in a Seattle newspaper. Gottsteins, which ran on Jan. 2, 1971, got more than a page (Gottstein died on Jan. 1, the universal birthday of all thoroughbreds, of lung cancer.)

In its obituary, The Seattle Times (Bob Schwarzmann working the keyboard), described Gottstein as the Laird of Longacres, calling him a short, bull-chested man whose well-kept body bounced back from cruel assaults by the surgeons scalpel.

Schwarzmann noted that Gottstein “ruled Washington horse racing with an iron fist and a soft heart,” that he “would thunder and roar and hurl ultimatums,” would “scowl, curse and threaten.”

Gottstein also presented “a steel-trap mind, capable of solving complex mathematical problems without pencil and paper. He was a scholar with an insatiable thirst for knowledge. He could recite, verbatim, intricate passages from his school days.”

For all of his civic clout, Gottstein probably would have been powerless, as were his heirs, the Morris Alhadeff family, from preventing Longacres closure and sale to The Boeing Company, in 1992. But his dream lasted for 59 years, a formidable legacy.

Check out David Eskenazis Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

Special thanks to the Museum of History and Industry

24 Comments

“For all of his civic clout, Gottstein probably would have been powerless, as were his heirs, the Morris Alhadeff family, from preventing Longacres closure and sale to The Boeing Company, in 1992.”

Bull Puckey. Mike Alhadeff sold out the horse-breeding and horse-racing community. I love the Wayback Machine–but this sentence is just wrong. The Alhadeff kids didn’t care about Longacres. I think they would have sold sooner, but Luella Gottstein had a home in perpetuity behind the tote board. It took 10 months from her death ’til the sale. Read Kelley’s column about it. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19900928&slug=1095441

I’m one of thousands who will never forgive the Alhadeff brothers.

“For all of his civic clout, Gottstein probably would have been powerless, as were his heirs, the Morris Alhadeff family, from preventing Longacres’ closure and sale to The Boeing Company, in 1992.”

Bull Puckey. Mike Alhadeff sold out the horse-breeding and horse-racing community. I love the Wayback Machine–but this sentence is just wrong. The Alhadeff kids didn’t care about Longacres. I think they would have sold sooner, but Luella Gottstein had a home in perpetuity behind the tote board. It took 10 months from her death ’til the sale. Read Kelley’s column about it. http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=19900928&slug=1095441

I’m one of thousands who will never forgive the Alhadeff brothers.

The Ms weren’t going to get anything for Ichiro no matter where they traded him. His on base% is below 300, which is unacceptable for a leadoff hitter, plus he’s only getting older. There are always a lot of defensive minded outfielders available, so there’s nothing to be disappointed about. There’s no conspiracy. Ichiro had 10 and 5 rights, so he could say no. Ichiro asked to be traded to a contender, the Yankees stepped up and offered a couple fringe prospects and Ichiro said yes.

Ross, no conspiracy suggested. They were lucky to get anything for Ichiro. Only thr Yankees would think they could rehab him, Ibanez style.

For me, the Mariners are akin to the Space Needle, the Market, SAM and any movie playing at the Cinerama … they’re just another attraction in the city, only less enjoyable.

Players come and go, talent is traded, management seems third-tier baseball savvy and the M’s aren’t close to being in the same league with the Rangers and Angels.

Flogging the tired story of what M’s management attempts, fails at or says … just doesn’t mean much anymore. Didn’t a sports’ brainiac once say, “They are what they are” … and about sums it all up.

Will, i sense story fatigue. I get that. Even Wedge referred recently to the repetitive style of losing as “Groundhog Day.” But unlike the other attractions, it is withiin the Mariners organization to change. They choose otherwise.

The current ownership/Lincoln/Armstrong team has demonstrated many times that they are penny-wise, pound-foolish, and unwilling to pay for a competitive team on the field. One point that many have missed: Nintendo has fallen on hard financial times recently and may well have ordered Lincoln to keep paring payroll. The Japanese management style is top-down, follow-orders,

ask-no-questions and Lincoln has had many years to absorb it. If you doubt that, note Armstrong’s statement at the farewell Ichiro press conference that the team had made a multi-year contract offer to Ichiro (say what?!?). Jack Z. and fans must demand the team set a 2013 payroll of $90-100 million or get the hell out of the way. Sad and continuing story.

Lou, neither Nintendo nor Yamauchi dictate payroll or, except for Japanese players, personnel issues, Just not in their world. The Nintendo losses affect Yamauchi’s wealth, not the Mariners fortunes. But you’re right about top-down mgt, and the offer to Ichiro.

I don’t see the M’s going after any major free agents. I think the debacle of Richie Sexson and disappointing seasons that Adrian Beltre had scares off ownership and with Ichiro gone few veterans will want to play on a young, rebuilding club unless they’re desperate to stay in the majors. Right now veterans would take a backseat to an up and coming prospect. With Ichiro here that would show that management does value veteran players but his trade shows that the M’s are definitely in a youth movement.

And except for Sexson and Beltre ownership has never gone hard after a big name free agent. They’re very conservative in their spending despite their claims that Safeco Field would give them the resources they need to be active in the free agent market. I’ve always wondered if ownership had a choice between having a losing club that made $15 mil in profit or a playoff participant club that made about $1.5 mil in profit in their respective seasons which club would they prefer?

Spending on veteran FAs is always a risky endeavor for any team. But the Yankees and a few other clubs can bury their mistakes. The Mariners, with Carlos Silva and Chone Figgins, still burn deeply as they should.

The Mariners owners until the last three yerars have spent enough to win. They just haven’t spent wisely.

Given their win steak @ 7, how many of these have been since the Ichiro trade?

If this keeps up, I see the makings of a good article on whether Ichiro was a plus or a negative.

It appears he may have been a drag on the club and since he is gone, perhaps Art can investigate whether there is any truth to this.

1coolguy, I will defer to Larry Stone’s blog item in the Times. He said the uptick is more coincidence than cause, not to mention mediocre opposition.I do think most players and certainly Wedge aare relieved that they no longer have to work around Ichiro’s privileges. He just doesn’t fit on this team, and it’s addition by subraction

Art, as always, probing and insightful. Many of us have found love at the bar, and the Mariners have found that in Wilhelmson. He may be a closer here for several years, having a 23 year old arm in a 28 year old, umm, ex-bartender. Here’s to life, love and booty.

Jack Z is easily better than Bavasi, and the ultimate village idiot, Woody Woodward. I can live with this bad marriage.

But, Mariner management should find out what Billy Beane makes, and double it. I’ve had it up to there with the A’s finishing ahead of the Mariners, year after year.

He probably wouldn’t take it, how could anyone work for Beavis and Butthead.

A’s years ago locked up Bean with a piece of the club. The Mariners tried, but wouldn’t dare give him equity.

There needs to be an article *specifically* detailing the horrible, destructive, un-baseball moves presided over by Chuckles and Howie, including all ill-timed public comments, quotes made by past Gms and managers, etc. There needs to be a huge expose on this that basically shames them into quitting. Especially Chuck. I understand Lincoln is the owner’s right hand man, but there’s no defendable rationale to Chuck’s continued presence. 28 years of “Leadership” resulting in the biggest pile of crap this side of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. This simply can’t go on. Its literally cruel and unusual punishment to every real baseball fan in Cascadia.

Effzee, understand your frustration, but all of us in the media have written versions of the story for years now. I recommend a new book, “Shipwrecked” by Jon Wells, who puts it all in one place very well.

My big disappointment as of late is that the departure of Ichiro apparently has not opened up more playing time for Figgins.

On a more serious note, though; it always scares me when Mariners’ players say they want to stay in Seattle. What they really are saying is that they have put their rapture over the surroundings, Seattle, etc. (an illness of its own) over the desire to be a winner. Really. Any player who wants to win has always known, with very few exceptions, and those exceptions comprise less than 20 percent of the Mariners’ history, that they are not going to win in Seattle. So players who say they want to stay here are saying they want to enjoy themselves, not win. In the bizarro world of Mariners’ baseball, we need to be keeping the players who want out and shipping out the players that want to stay.

Michael, players are always gratuitous in their comments about the home team. Here, and everywhere. Like the rest of us, they care about finding jobs and money. Saying anything bad about team and town only cuts their chances. Their agents are scrupulous about training them. See, LaLoosh, Nuke.

Yes, this is about the M’s. After 26 years in the NW I now live in a sunny, warm state. I used to think the people up there had “Megan Black Disease”. It would be rainy and ugly all day. About 4:30PM there would be a sun break. At 5 Megan Black would come on her weather cast and gush about how it was a “Beeee-yoooo-tee full” day in the NW. After 26 years of mostly misery as an M’s fan, I think M’s fans have some variation of that disease. The M’s lose game after game, year after year, and what is the fan response? They wear yellow shirts and show up when Felix pitches. What they should be doing is refusing to show up at all until Howie and Chuckles fall on their swords. Whether Ichiro fails or succeeds, he is in a far better place now. As to the rest of it, the M’s will continue to give up future stars for pitchers who can’t pitch and batters who can’t bat. What Art did not mention is, how many of those first round picks between 1996 and 2009 are now thriving, or at least contributing, somewhere else. I don’t know the answer, but I bet it is an interesting one.

Quite a few the draftees flourished elsewhere, but I flogged that horse previously.I do believe you’re right about some in the fan base. They are numb. As am with happy-talk weather.

who did the M’s draft instead of Mike Trout?? Maybe they can sign Raoul and claim next year as bring back the memories??

In the 09 draft, Strasburg went No. 1 and Ackley No. 2. Trout went 25th. So 22 others, including Billy Beane, whiffed too.

No conspiracy. There was a small market, and only the Yankees have a history of success with players on the decline. Going to the Yankees saved some face, but Ichiro would and could have said no. The market was minimal. Addition by subtraction.

You missed one thing about the return for Cliff Lee: it was Josh Lueke that got us John Jaso in a trade from Tampa. So, the current return is Beaven (agreed, mid- to late-rotation guy at best, but potentially a serviceable part), and Jaso (currently the best hitter on the team, though that of course says more about the bats on the roster than it does about Jaso).