By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Going back to the mid-1930s, when the Pacific Coast Leagues Seattle Indians were sued for $254 over an unpaid lumber bill, area sports fans have borne witness to a lot of athletic-related litigation, some significant, some frivolous.

In the early 1970s, SuperSonics star Spencer Haywood sued the City of Seattle for a knee injury that he suffered when he slipped on a wet Coliseum court (Haywood sought more than $400,000; the sides eventually settled).

In the mid-1970s, Vince Abbey, owner of the Western Hockey Leagues Seattle Totems, sued the National Hockey League after the NHL first granted, then jerked, an expansion franchise from him. That case dragged on for 10 years before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals threw it out.

With Abbeys lawsuit in its formative stages, shareholders in First Northwest Industries, parent company of the SuperSonics, sued club co-owner Sam Schulman, accusing Schulman of squandering $2 million on ill-advised player acquisitions (only time we know of when a team effectively sued itself).

In 1984, the Mariners sued the Seahawks to resolve the issue over which club held rights to use the Kingdome on Sunday, Sept. 2 (the Mariners prevailed, forcing the Seahawks into playing an unscheduled Monday night game).

No civic legal spat, whether team vs. team, player vs. team, coach vs. school (Rick Neuheisel vs. the University of Washington), or former owner vs. current owner (Howard Schultzs unsuccessful 2008 attempt to get U.S. District Court in Seattle to rescind his sale of the Sonics to Clay Bennett), provided greater intrigue (even if a lot of the testimony seemed tedious), or had a more lasting impact, than one that occurred 35 years ago.

In that case, which resulted in an 18-day courtroom drama, a coalition of local government agencies — Washington state, King County, City of Seattle — sought to make the American League pay for the sporting atrocity of yanking the Seattle Pilots out of town after just a single year (1969) of residency.

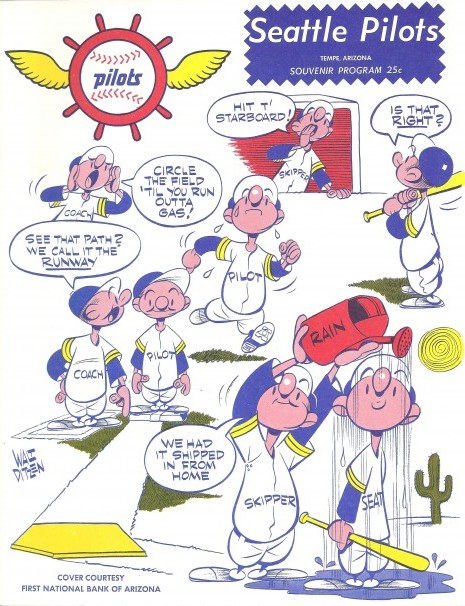

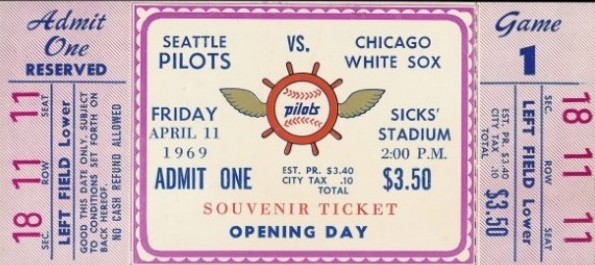

The particulars in that matter have been well hashed (see Wayback Machine: A Fire That Changed Our Sports), but briefly: the American League awarded Seattle an expansion franchise at the 1967 winter meetings in Mexico City on two conditions: In exchange for a team, Seattle would build a domed stadium to be completed by no later than 1972 (King County voters said yes on Feb. 13, 1968), and would have to fund a major refurbishment of Sicks Stadium for the team’s interim use, principally increasing its capacity from 12,000 to 30,000 (the city spent nearly $700,000 to make this happen).

Seattle probably should not have been awarded a team under any conditions: it wasnt ready, politically and especially financially. But Washington senators Scoop Jackson and Warren Magnuson strong-armed major league owners by threatening to eliminate baseballs anti-trust exemption unless Seattle was awarded a team.

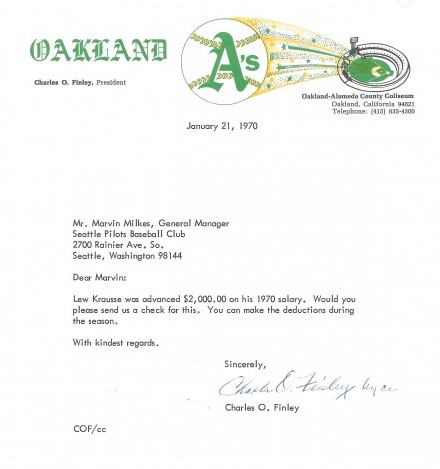

A date change to baseballs expansion timeline didnt help Seattle’s initial entry into the American League, either. MLB originally planned to add four expansion franchises in 1971, but pushed up the schedule to 1969 when Missouri Sen. Stuart Symington also threatened to strip baseball of its anti-trust exemption if Kansas City did not get a team — immediately — to replace the Athletics, whom owner Charles O. Finley had just spirited off to Oakland.

The timeline escalation gave Pacific Northwest Sports Inc., which owned the soon-to-become Pilots, scant time to secure adequate financing to supplement the 47 percent share of stock that had been purchased by absentee majority owner William Daley, former owner of the Cleveland Indians.

So the Pilots began their first season under-capitalized (major minority owners Dewey, former general manager of the Seattle Rainiers, and dapper brother Max Soriano, a legal counsel for the PCL, borrowed heavily to acquire their 35 percent interest), without a television affiliate and with the new paint literally still wet at Sicks Stadium.

They also had a rival group headed by restaurant owner and Washington Husky fanatic Dave Cohn and car dealer Joe Gandy, who had served as president of the Century 21 Exposition (1960-63) undermining their efforts.

(Of the $2 million put up by the Sorianos, two-thirds of it was in Max’s name because Dewey was going through divorce proceedings.)

“Dave Cohn wanted to be part of the Pilots but he didn’t want to put up any money,” Max Soriano complained to the Post-Intelligencer in a 2005 interview. “Cohn was our biggest nemesis. We wouldn’t let him be an officer of the club unless he bought stock. Everybody else paid for the stock. We had a rift right there. We did not do well because we didn’t have the money we should have had or could have had or may have had.”

Dewey and Max seemed perfectly suited to become Seattle’s first major league owners. Both had been all-city pitchers for Franklin High School. Dewey served as general manager of the Seattle Rainiers and president of the Pacific Coast League following his playing career, which included three stints with the Rainiers (1939-42, ’46, ’50-51). Max pitched in college at Washington, well enough to make the Huskies’ All-Century Team, and then went to law school. He later fused his interests by becoming the PCL’s legal counsel.

Dewey became a flamboyant front man, calling all the shots and issuing official statements on behalf of the club. Unfortunately, things started going south before the 1969 season even commenced when the Sorianos allowed GM Marvin Milkes to trade a promising outfielder named Lou Piniella to Kansas City (Piniella went on to become the American League Rookie of the Year).

An early sign that the Pilots probably weren’t going to make it came on May 6-7 when the Boston Red Sox came to town for a two-game series. With the weather ideal, the Pilots expected to draw between 15,000-18,000 for each contest. Instead, the games attracted crowds of 9,427 and 7,084, respectively.

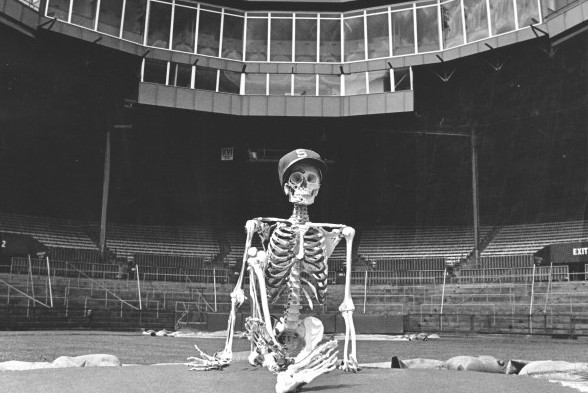

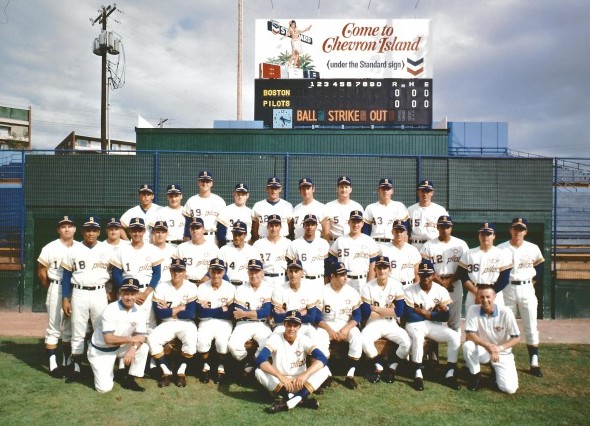

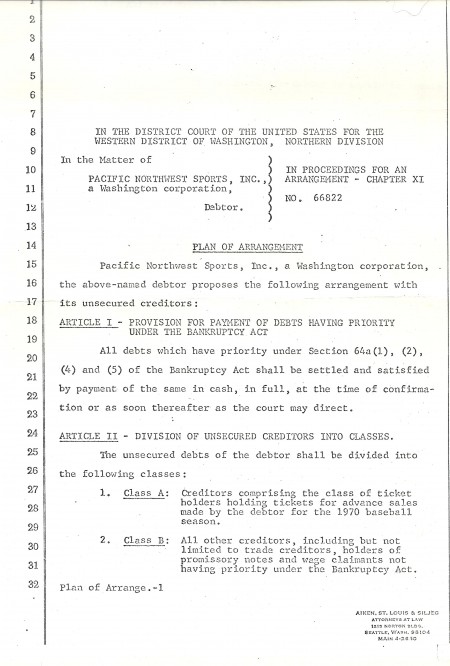

By the end of that series, the Pilots stood 8-17, nine games out, and they never recovered, finishing 64-98 and 33 games out of first while drawing 677,944 customers. One month after the season, chronicled best perhaps in “Ball Four,” the best-selling book by Jim Bouton (a knuckleballer, Bouton spent most of the season with the Pilots before they traded him to Houston) , the Pilots launched bankruptcy proceedings.

The team remained in limbo until the spring of 1970. No one was sure whether the players would report to Seattle. Thus, when spring training ended, the Pilots’ equipment was moved to Provo, Utah, where truckers waited word on whether to drive to Seattle or elsewhere.

At the bankruptcy hearing, Milkes testified that the team did not have enough money to pay the coaches, players and office staff. Had Milkes been more than 10 days late in paying the players, they all would have all become free agents, leaving Seattle without a team in any event.

With that in mind, federal bankruptcy referee Sidney Volinn declared the Pilots insolvent April 1, six days before Opening Day, which cleared the way for them to relocate to Milwaukee, where a group headed by car dealer Bud Selig had become an avid suitor.

Selig still chafed over the 1965 move of the Milwaukee Braves to Atlanta and tried — unsuccessfully — to lure the Chicago White Sox to Milwaukee. Selig also failed to land a National League expansion franchise in 1969. Once the bankruptcy court ruled, MLB issued a quick approval for the sale of the Pilots to Selig’s group.

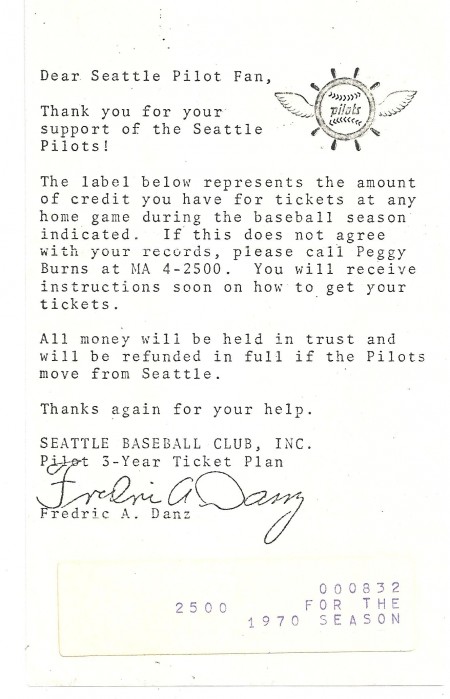

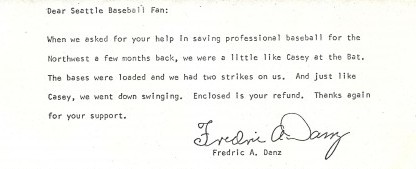

In the months before the relocation, various Seattle entities scrambled to purchase the Pilots so that they could remain in Seattle. Theater owner Fred Danz, a philanthropist who sat on and steered a variety of corporate boards, made an offer that MLB deemed too thinly financed.

When no one else with wherewithal emerged as potential buyers, civic activists Eddie Carlson, Jim Ellis and Jim Douglas mobilized business and labor leaders and members of the public, the collective agreeing to contribute to a non-profit entity which would buy the Pilots at the existing owners’ asking price, then run the club on a community-benefit basis. Carlson et al succeeded in raising the money but fell a couple of votes shy of American League approval.

The American League could have prevented the Pilots from moving to Milwaukee simply by voting against it, but elected not to, determining that Seattle did not have the appetite or finances to support a major league operation. There was another factor in play: a concessionaire with clout.

So the Pilots became just the second team in the 20th century to relocate after just one season (the only other time, oddly enough, was when the original Milwaukee Brewers became the St. Louis Browns following the 1901 season).

A few months before the Pilots departed, after correctly assessing Seattle’s baseball situation as dire, the state’s attorney general. Slade Gorton, and King County Executive John Spellman asked Seattle attorney William Dwyer if he would represent the state and the county in making a legal effort to keep the Pilots in Seattle.

Dwyer was unable to do that, despite his futile protest during bankruptcy proceedings that Seattle deserved more than one year to demonstrate it could support the Pilots.

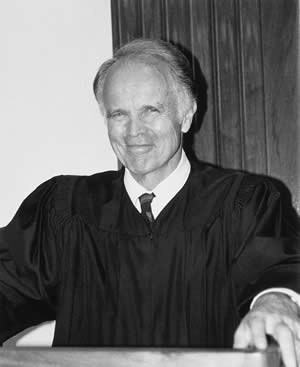

Dwyer’s career as a litigator and judge in Washington state ultimately spanned 40 years. The son of a stenographer and truck driver, Dwyer grew up on Queen Anne Hill and worked his way through high school, the University of Washington and New York University law school doing all sorts of odd jobs, including copy boy at The Seattle Post Intelligencer, cab driver, dishwasher and waiter.

Dwyer spent 34 years as a trial lawyer, arguing a variety of cases. Notably, he successfully represented state legislator and alleged Communist sympathizer John Goldmark in a libel suit against the Tonasket (Okanogan County) Tribune, and he went to bat for newspaper employees in the contested proposal for a joint-operating agreement between the Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

After President Reagan, at the recommendation of Republican senators Gorton and Dan Evans, appointed Dwyer a U.S. District Court Judge on Dec. 1, 1987, he made a number of landmark rulings, none more famous or controversial than his 1991 decision that ordered the U.S. Forest Service to stop permitting logging on 60,000 acres of ancient forests in order to protect an endangered species, the spotted owl.

Dwyers ruling led to a forest summit called by President Bill Clinton in 1993, which changed the manner in which the government managed national forests.

Everyone who knew Dwyer considered him a renaissance man. He wrote books (his last, In The Hands of the People, served as a vigorous defense of the jury system), acted, reveled in the outdoors (he scaled many Cascades peaks), owned an oyster house, collected art, absorbed history and quoted Shakespeare.

Dwyer reached his mid-career as a trial lawyer when Gorton and Spellman asked him to take on the American League.

Long after the trial, Dwyer told interviewers that, going in, he considered it an unusual case in the sense that he would have to prove the existence of an “implied contract” and its breach by the American League. His prime objective: return baseball to Seattle.

Dwyers case hinged on his claim that a contract was created between the American League on one side and the state, county and city — in effect, the people — on the other, and his contention that the American League had violated it.

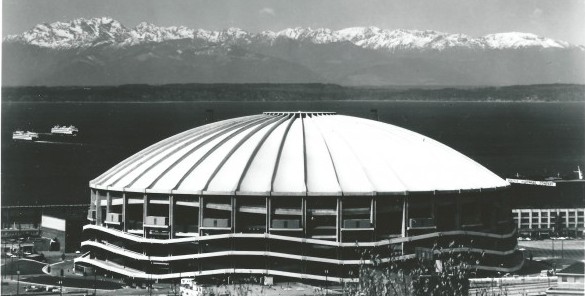

Dwyer argued that the “implied contract” called for the American League to place an expansion franchise in Seattle and keep it there. In return, citizens, through the government, would (a) spend money to repair an aging Sicks Stadium for the teams temporary use and (b) support a $40 million bond issue to fund a domed stadium. Upon its completion, the team would move from Sicks Stadium into the new ballpark, becoming its prime tenant.

The existence of the implied contact had as its basis well-documented communications by American League representatives, who came to Seattle and made public statements in support of the bond issue. In advance of the stadium vote, the AL dispatched a parade of luminaries, such as A.L. President Joe Cronin, and players notably Carl Yastrzemski, Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams to Seattle to urge voters to pass the bond issue. In response to that lobbying, voters approved it.

The breach occurred when the American League allowed the Pilots to leave town in the face of credible offers (Danz, Carlson) to keep them there — especially after citizens held up their end of the bargain: Sicks Stadium had been refurbished, the King County Domed Stadium was on the way.

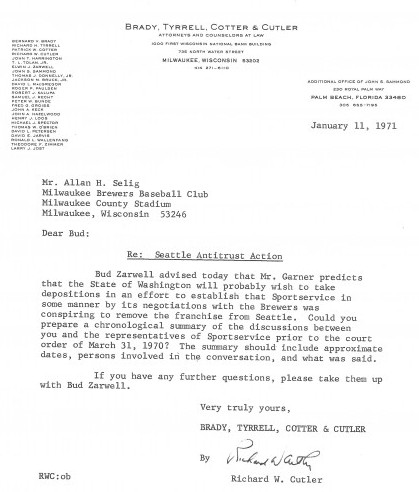

At the time, many Seattleites wondered why MLB jerked the Pilots after just one season. Dwyers contention: the breach had been carried out in part because of an illegal (antitrust violation) tying arrangement with Minneapolis-based concessionaire Sportservice, one of the countrys major purveyors of hot dogs, peanuts, soda pop and beer.

Sportservice extended credit to a number of MLB franchises in return for exclusive, long-term concession contracts at their ballparks, the Kansas City Athletics among them. The Sportservice-Athletics arrangement stipulated that if the As ever moved, Sportservice would follow them to their new home.

The Athletics relocated to Oakland in 1968, but Sportservice could not follow because the Oakland Coliseum already had a concessionaire under contract.

Facing a substantial loss of business, Sportservice sued the As for breach of contract. The As countersued, claiming their contract with Sportservice, signed decades earlier by previous owners, violated antitrust laws.

Sportservice provided $2 million in funding to Pilots owners (the Soriano brothers) to help get them into the American League. In exchange, Sportservice became the exclusive concessionaire at privately owned Sicks Stadium.

But local law held that a potential concessionaire (or any vendor) was required to undergo a competitive bidding procedure if it hoped to do business in a public facility such as the Kingdome, a county property.

Thus, Sportservice would not automatically follow the Pilots there another bite out of its business. Sportservice wanted the franchise in a location that had no competitive bidding for stadium concession rights.

But if the Pilots moved from Sicks Stadium to a privately owned facility, such as the one in Milwaukee, Sportservice could follow them there (Dewey Soriano stated emphatically that if Sportservice could not do business in the Kingdome, the Pilots wouldnt, either).

In fact, Sportservice followed the Pilots to Milwaukee.

Our claim was that the team was removed from here (Seattle) in the course of enforcement of an illegal exclusive dealing arrangement: A tying agreement, Dwyer told an interviewer.

Dwyer filed suit against the American League on behalf of Washington citizens in the fall of 1970, after the Brewers played their first season in Milwaukee. He alleged breach of contract, fraud and antitrust violations (even though baseball was exempt from prosecution under antitrust law).

But the case didnt get to trial until January of 1976 because it was continued a number of times in order to give the American League and Washingtons government entities an opportunity to reach a settlement with the aim of securing for Seattle a new major league team.

To that end, Dwyer, Spellman and Gorton became frequent guests at Major League baseball meetings, in which owners assured them that Seattle would receive a team to replace the Pilots — but only if the lawsuit were dropped.

Dwyer, Spellman and Gorton wanted to give MLB the benefit of the doubt, but recognized that if they dropped the suit, it would have been easy for MLB to wash its hands of Seattle. So Dwyer told MLB that he would drop the suit only after a team was in place and playing in Seattle under an unbreakable lease.

During the course of these meetings, talk arose about moving an existing team to Seattle. At one point, Oakland was mentioned and, later San Diego. The implication: Seattle would receive one of those teams in exchange for dropping its suit. But Dwyer persisted: hed be willing to talk only when the American League made a specific offer on a binding contractual basis. The American League wouldn’t do that. So with the sides at loggerheads, the case went to court.

On the morning of Jan. 11, 1976, only hours after Bill Russells Sonics had been drubbed 125-104 by Bob McAdoo (38 points) and the Buffalo Braves, Dwyer squared off against American League lawyers in the Snohomish County Courthouse in Everett, judge Frank Howard presiding. The plaintiffs sought a major league team to replace the Pilots, plus more than $7 million in damages.

Dwyer and Jerry McNaul represented the state and county, and Lawrence McDonnel acted on behalf of the city. David Waggoner of Seattle and John Ferguson of Cleveland represented the American League. The witness list included several major league owners, plus Mantle, Williams and various Pilots principals.

Howard swore in a jury of nine women and three men. Of the 12, just one juror had ever purchased a ticket to a Pilots game. Another had watched the Pilots once, for free, from Tightwad Hill, above Sicks Stadium.

The American League contended that the Pilots were broke, and that a federal bankruptcy court had approved the sale of the team to Milwaukee as the best means of satisfying creditors. Dwyer argued that sufficient money had existed to operate the franchise in Seattle beyond one year, and that the teams losses were paper losses.

MLB charged that the Pilots were mismanaged. Dwyer countered that good management could — and would — have eliminated real operating losses, even in the teams first season.

MLB said Sicks Stadium was inadequate as a major league facility, even as a short-term solution. Dwyer dispatched a photographer to other AL cities and had as potential evidence shots of ballparks that made Sicks Stadium look good by comparison, notably Cleveland Municipal Stadium and Tiger Stadium in Detroit.

“Some of them, Dwyer said, you couldn’t sit down without getting a splinter, and the plumbing was nothing to write home about.

MLB argued that Seattle failed to support the Pilots, who drew 677,944. Dwyer countered that the Pilots outdrew the Padres (512,970), Phillies (519,414), White Sox (589,546) and Indians (619,970), all long-established clubs save San Diego and none of those franchises moved.

After Ferguson, one of the American Leagues lawyers, accused the state of a shakedown by seeking millions in damages, Dwyer countered that the AL made an unprecedented effort to block the trial.

We have been hit by a barrage of motions for summary judgment in every single phase of this case, the likes of which none of us have ever seen before, Dwyer told the court.

As part of his opening statement, Dwyer disclosed that owners of the Pilots and Brewers entered into secret negotiations for the sale/purchase of the team in August, 1969 (a month before the end of that years regular season), and that those talks included a sale price of $13 million for a team that Pacific Northwest Inc. had paid $5,350,000.

In October of 1969, one month following the final out of the Pilots season, Hy Zimmerman of the Seattle Times wrote a column in which he quoted Daley, Pacific Northwest Inc.s principal shareholder, to the effect that Daley would give Seattle one more year to support the Pilots. Cronin claimed Zimmermans column was the final nail in the coffin for AL owners that the team should be moved.

During the 1969 World Series, Pacific Northwest Inc. and Milwaukee reached a handshake agreement for a $10.8 million sale and move of the Pilots (Selig testified the sale agreement was reached Oct. 11, 1969, during the eighth inning of the first game of the World Series in Baltimore).

The same month, and in a piece of skullduggery that eventually buttressed Dwyer’s case, Seligs Milwaukee group and Sportservice entered into a loan agreement to help Selig acquire the Pilots. Dwyer contended that a conspiracy existed to sell the Pilots and move them to Milwaukee. AL attorney Waggoner said Dwyers conspiracy to move the Pilots amounted to sheer nonsense.

But Dwyer put a variety of witnesses on the stand, including a number who favored the American Leagues position, to demonstrate that wasn’t so.

It was clear Bill Dwyer had devised a legal theory behind this case that was unique in courtroom annals in America, Fred Brack, who covered the trial for the Post-Intelligencer, told seattlepilots.com.

To buttress the evidence for this theory, he relied on the testimony of the witnesses the lords of baseball. He would ask them questions very good questions, never long, difficult, never argumentative as you see in courtroom cases on television or in movies.

“He would ask them simple questions, but very pointed. The witnesses would, if they comprehended the question, which often they did, would begin to squirm and try to avoid answering that question because to answer it directly and forthrightly would not do their case any good. It would buttress Bill Dwyer’s case.

“The jury was clearly in Bill Dwyer’s pocket from almost the moment when he made his opening statement.

A key piece of Dwyer ammunition: He had transcripts of private meetings of American League owners. Those documents not only formed the basis of many of Dwyers questions, they set up American League owners to hang themselves through their own words.

Ellis, the architect of Forward Thrust, became the plaintiffs first witness and testified that the decision to include funding for a domed stadium in the $40 million Forward Thrust package was made on the strength of an American League resolution granting Seattle a franchise.

We placed a great deal of reliance on the American League resolution, Ellis said. We assumed there would be a team in Seattle and it would be a major tenant of the new stadium.

Ellis also testified about Cronins trips to Seattle, aimed at pushing for approval of the stadium bond issue.

Dwyer argued that the American League had options other than relocating the Pilots to Milwaukee. It could have called on principal shareholder Daley to ante up more cash. Or, it could have allowed Danz more time to raise money for a potential purchase of the team. Or, the American League could have approved the sale of the Pilots to Carlsons non-profit group. Dwyer emphatically demonstrated that the American League never lifted a finger to keep the Pilots in Seattle.

We claimed, Dwyer later explained, that the owners had engaged in a whole series of acts designed to make sure that the Carlson/Ellis/Douglas offer would go away. One of those steps was to impose unmeetable conditions.

When Bob Short, former owner of the Washington Senators who had zero sympathy for Seattle losing the Pilots, took the stand on Jan. 20, both to his chagrin and the courts (the judge frequently admonished Short to answer the question), he stated that Carlsons funding plan amounted to a sham because there would never be any profits.

I was opposed to bringing in a non-profit partner to a business operated for profit, testified Short, one of four American League owners who voted against the Carlson plan. Short also blasted Sicks Stadium as being inadequate.

Asked by Dwyer if Sicks was a very good, small stadium, Short said, I found it a very bad small stadium, at which point Dwyer read from a 1973 deposition in which Short said, It wasnt a bad small stadium.

When Short took the stand for a second day of questioning, Dwyer introduced a transcript from an American League owners meeting in February 1970 that showed the American League guilty of practicing revisionist history.

The transcript revealed that the American League had doctored a resolution to keep the Pilots in Seattle in perpetuity by editing it to tentative. Short had approved of the doctored resolution.

Dwyer put Cronin on the stand to show jurors that Cronin played roles in the decision to place a stadium bond issue before King County voters, and in the subsequent campaign that led to its passage. Cronin, who gave rambling, evasive answers, admitted he had a voice in the architectural plans for the domed stadium, and also conceded that he had traveled to Seattle in January and February of 1968 to help get the bond issue passed.

What was clear during Cronins testimony was that he was doing a great damage to the American League’s case, even though he was the American League president, Brack told seattlepilots.com. “At the end of his testimony, when he was dismissed, he rose in front of the jury from the witness stand, climbed down, walked across the courtroom and stuck out his hand and shook Bill Dwyer’s hand in front of the jury, after making a fool of himself, frankly, in his testimony.”

Dwyer used another transcript of an American League owners meeting that took place on Jan. 27-28 in Berkeley, CA., to make Oakland As owner Charles O. Finley admit that he said, The city of Seattle and the state of Washington would have us where they wanted us with regard to a possible move of the Pilots to Milwaukee.

Finley conceded that the AL had taken no steps to keep the Pilots in Seattle, or made any demand of Daley that he live up to his promise to sufficiently underwrite the Pilots. Finley added that Daley got the franchise only because Daley said he would guarantee the operation if it ever got in trouble.

At one point, when Finley left the stand for a recess, he walked by Dwyer and said, Youve been doing your homework, havent you, pal?

Brack put it this way: He (Dwyer) was so well prepared that it was breathtaking. He was so well prepared that it was just awesome.

When Spellman took the stand, the judge would not allow the jury to hear his testimony that American League lawyers had told him 14 months before the start of the trial that Seattle would never receive a franchise if the trial started. The judge deemed such testimony inflammable.

But the jury did hear Spellman testify that by the fall of 1969, King County sold $10 million worth of general-obligation bonds for stadium construction and had purchased a site for the stadium near the Seattle Center. Under Dwyers questioning, Spellman testified that when King County voters met the ALs conditions for a franchise, a contract had been formed.

A considerable amount of settlement conversation occurred during the trial. In those negotiations, Dwyer told American League lawyers that plaintiffs would demand a substantial monetary payment to cover the costs of the litigation, and that the City of Seattle would demand a $750,000 payment for the money it spent refurbishing Sicks Stadium. Dwyer added that the state of Washington would no longer be willing to settle for the placement of a team in Seattle without additional compensation.

Given the damages it faced if it lost, given that Dwyer had turned some of its own witnesses into the legal equivalent of exploding cigars, and especially given that the case Dwyer presented had destroyed the credibility of the American League’s arguments, the league caved Feb. 14. It marked the the first time that a major league franchise had been secured through litigation. In legal fees, it cost the state $330,000, the county $217,500 and the city $32,500. It could have been more, but Dwyer dropped his normal $75 per hour fee to $35.

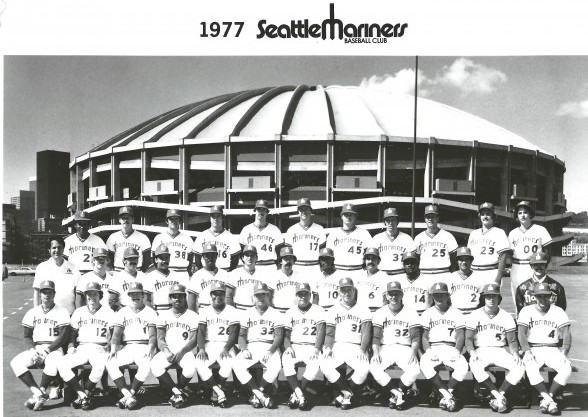

The settlement resulted in the creation of the Seattle Mariners with a 20-year lease. Given the American League’s duplicitousness, Dwyer did one other interesting thing. The agreement between the American League and Dwyer stipulated that the Snohomish trial would not end, but be recessed and continued for more than a year enough time to make sure that the Mariners were in uniform and playing baseball in the Kingdome.

Without Dwyer’s legal wizardry, there would have been no Ken Griffey Jr., no Big Unit, no Edgar, no Jay Buhner Buzz Cut nights, no Lou Piniella, no 1995, no Ichiro, no 2001, and no Dave Niehaus and his grand salamis. What a tremendous legacy — a major league franchise — to bequeath a region.

Bill Dwyer lived long enough to watch the Mariners go from wretched to spectacular. Diagnosed with lung cancer in March of 2001, he made it to Feb. 12, 2002, before dying at his home in downtown Seattle. The last Mariner team he saw won 116 games.

———————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

5 Comments

The piece says, “The Mariners continuing futility shouldnt rest only on Ackley . . . .” I broke out laughing when I read that line. No, “[t]he Mariners’ continuing futility” has a foundation a bit beyond any one player, or ten players for that matter.

Well, Michael, I think we all know that. But I called him out, and felt compelled to toss him a fig leaf.

So winning 13 of their last 20 games (and all three losses in Chicago were very winnable) is considered “continuing futility?” I guess I’m seeing it differently than you guys are. I’m seeing a young team still learning how to win games at the MLB level (and starting to figure it out) while you two are seeing “same old Mariners” after a couple of losses to the Angels.

I’ve said this so often I should use it as a mantra while meditating, but 2012 is about progress and experience. ALL of us (including Zduriencik and Wedge) are learning who can play at this level and who can’t. The Mariners aren’t that far away from being a decent team: They’ve got loads of pitching (including the minors) and they can get it done in the field. The “continuing futility” remains in the batter’s box and I think there’s a chance Zduriencik might want to do something about that in the off-season.

On the whole, though, I like the direction the franchise is going. This is not 1980.

You wrote, “I’m seeing a young team still learning how to win games at the MLB level (and starting to figure it out) . . . .”, with the latter part, in parenthesis, obviously open for debate on any real higher level. However, my point is that your statement could have been said, and has been said, during just about every Mariners’ season since day one, barring a five year or so stretch starting in the mid-90’s. Interesting that you also feel compelled to argue, or raise the point, that 2012 is not 1980. I will be the first to get excited if the Mariners ever really put it together, but in the meantime I have to lean with Art’s sentiment that it is quite possible that after this year the Mariners could be the only team never to make the World Series. Conversely, I was down in Brentwood tonight and you should hear people talking about the Dodgers and the “bats” that have been added as of late. I just don’t see the Mariners pulling off something that even brings one bat of that caliber to Seattle.

It’s absolutely possible the M’s could be the only team to never reach the World Series after this year, although Cubs fans might ask what that’s worth.

I’m not advocating getting excited about a sub-.500 team. I get that. I’m just saying that the Mariners have slowly improved as the current season has progressed, and that a pair of losses to the Angels isn’t worth going into Here-we-go-again mode.

It’s been frustrating as hell to see what has happened with this franchise since 2003 and “patience” has been an overworked word, but I’m going to remain optimistic. If I wanted to be a pessimist, I’d be a Cubs fan.