By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Several days after the July 6, 1948, straight-cash sale of Rainiers outfielder Lou Novikoff to the Newark Bears of the International League, Seattle Times baseball beat man Emmett Watson, later a popular columnist and author, wrote a lengthy piece lamenting the departure of The Mad Russian, who had, in Watsons view, done more to enliven Sicks Stadium than any player in the three years Novikoff spent with the club.

He is the greatest scene stealer in baseball, Watson penned. If there is a dramatic fly ball to be dropped, Lou satisfies everyone. He drops it. If the fans start to boo him, he undresses the second baseman with a line drive. If he hits a home run, he trots around the bases and kisses home plate. Hes the only player Ive ever seen kiss home plate after hitting a home run.

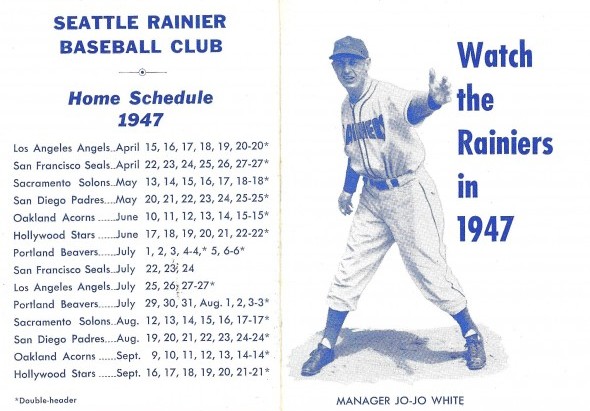

Slightly more than a year earlier, June 22, 1947, the Rainiers played a Sunday doubleheader with the Hollywood Stars at Sicks Stadium, and the 6,565 fans in attendance witnessed just the sort of spectacle Watson described.

The Rainiers rallied in the final innings of the first game to wipe out a 4-3 lead built by the Stars when Seattle starter Bill Posedel couldnt get the side out in the seventh inning. Left-hander Charley Ripple replaced Posedel and stopped the Hollywood rally, receiving credit for the win, while Rex Cecil finished out the last two innings after manager Jo Jo White lifted Ripple for a pinch hitter.

The Rainiers scored three times in their half of the seventh when Bob Johnsons pinch double drove in the tying run and Novikoffs double (on a 3-and-0 count) drove in two more runs. Novikoff also hit a home run in the first inning, over the right-field fence, off Rugger Ardizoia with White aboard. Final score: Seattle 6, Hollywood 4.

Tom Reis starred in the second game for the Rainiers, hurling a two-hitter to win the series clincher, 3-2. Hollywood scored its runs in the second inning, Seattle equalized in its half of the frame and Novikoff stole the show in the fifth.

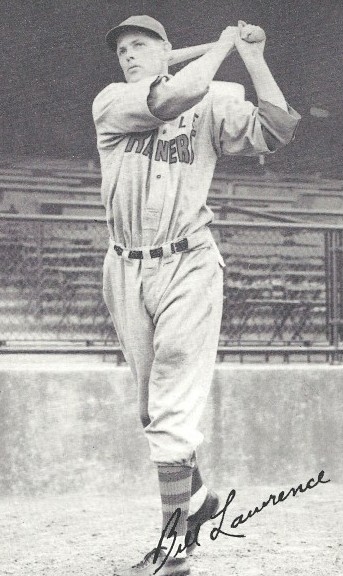

Novikoff not only hit the game-winning home run, over the left-field fence, he became just the fourth man to hit homers over both the left-field fence and right-field fence at Sicks Stadium in the same game, joining Bill Lawerence and Blas Monaco of Seattle and Vince DiMaggio of Oakland.

Novikoff also became the only one of the four to fall to his knees halfway between third and home on his scoring trot, crawling the rest of the way to the plate to plant a smacker on it.

When Novikoff returned to the Seattle dugout, teammate Sig Jakucki took hold of both of Novikoffs ears and planted a kiss on each cheek. Backing off with a chuckle, Novikoff said, Wait until the United Nations hears about this. A Pole kissing a Russian.

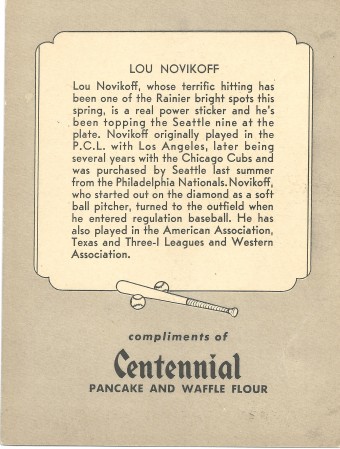

The Mad Russian, not to be confused later with The Mad Hungarian, Al Hrabosky, came to the Rainiers in 1946 when the club purchased his rights from the Philadelphia Phillies, with whom he’d failed a post-World War II major league comeback attempt.

Novikoff arrived in Seattle as a major celebrity. As Arthur Daley wrote in the New York Times, Looie was afloat in a wave of publicity from the moment he arrived in the big leagues until the moment he left.

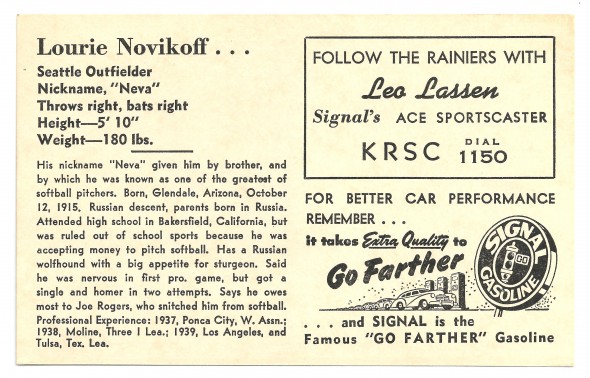

Remarkable that Novikoff made the big leagues at all. Born Oct. 12, 1915, in Glendale, AZ., to Russian immigrants Alexander Ivanovich Novikoff and Julia Simonova Zadorkin, Louis Alexander Novikoff grew up in Bakersfield, CA. One of 12 children, he attended Kern County High School in the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley, and learned baseball on the sandlots before launching operations as a fast-pitch softball player.

As a high school student, Novikoff joined a professional softball league in Southern California, playing under the name Lou Neva in order to preserve Lou Novikoffs amateur status, a ruse that failed.

When Kern High found out that Novikoff had accepted money for playing softball, it banned him from prep athletics, seemingly ending his baseball career.

Undaunted, Novikoff became a sensation as a fast-pitch pitcher and hitter — such a sensation (he once fanned 22 in eight innings) that in 1937 the Chicago Cubs stunned baseball by offering him a contract.

At the urging of Joe Rodgers, who operated a semipro team in Long Beach, CA., Novikoff decided to give the Cubs a whirl, figuring, correctly, that the money in baseball beat the money in softball. The Cubs assigned Novikoff first to Class C Ponca City, OK., of the Western Association.

Unlike Seattles Bob Fesler (see Wayback Machine: The Bob Fesler Experiment), a softball flinger who signed with the Seattle Rainiers in 1955 and largely failed to make the transition from the 45-foot, softball-pitching distance to the 60-foot-6-inch baseball distance, Navikoff restricted himself to hitting in the minor leagues and succeeded beyond anyones expectations.

At Ponca City in 1937, Novikoff hit .351 and won the leagues batting championship. At Moline (IL.) in 1938, he batted .367 and won the Three-Eye League crown. In 1939, he moved to Class A Tulsa of the Texas League and hit .368 in 110 games, winning that leagues batting title.

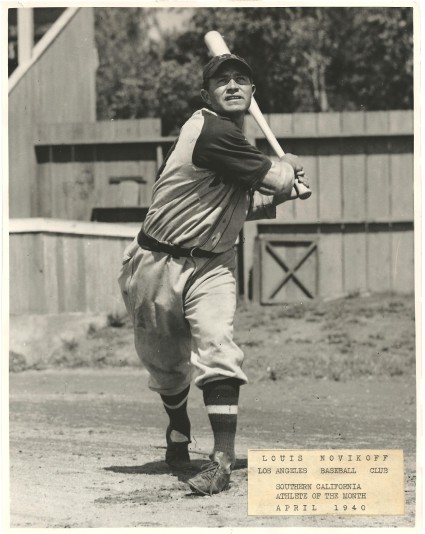

Novikoff also got in 36 games for the AA Los Angeles Angels that year and hit .452. The Sporting News named him its Minor League Player of the Year.

Novikoff played in 174 games for the 1940 Angels and hit .363 with 41 home runs and 259 hits, winning the Pacific Coast League batting title. A year later, with Milwaukee of the American Association, he hit .370, winning that leagues batting title.

Everywhere Novikoff played, he became famous for chasing bad, even horrendous, pitches, frequently knocking them out of the park, or nearly so.

I remember a doubleheader with the old Hollywood Stars, Frank Finch wrote in the Los Angeles Times. Lou went something like 6-for-8, and no two pitches were the same and none was a good pitch.

After tearing up the American Association for 90 games in 1941 (.370 BA), the parent Cubs could no longer ignore Novikoff and summoned him to play under manager Jimmie Wilson for the seasons final 62 games. Novikoff struggled, hitting just .241.

Novikoff came back and hit an even .300 in 1942, an average he achieved only with an assist from St. Louis pitcher Johnny Beazley. In Novikoffs last at-bat of the season, he needed one hit to reach .300.

The kind-hearted Beazley gave it to him, wrote The Sporting News. The Clouting Cossack swung mightily, but dribbled one near the mound. However, the pitcher took his time fielding the ball and Novikoff had his hit.

Novikoff never approached the stratospheric stats he compiled in the minors during his years in the majors (1941-46), the tainted .300 in 1942 his high mark.

A home run hitter in the minors (41 for the 1940 Angels), Novikoff never hit more than one home run in a major league game, produced just three four-hit games, and never drove in more than four runs in any contest.

But, as Daley of The New York Times pointed out, no player during Novikoffs time generated as much publicity as The Mad Russian, who became a one-man gate attraction in part because his career coincided with the absence of many major league stars, off performing military service during World War II, and in part because of Novikoffs engaging personality, flair for drama and supreme quirkiness.

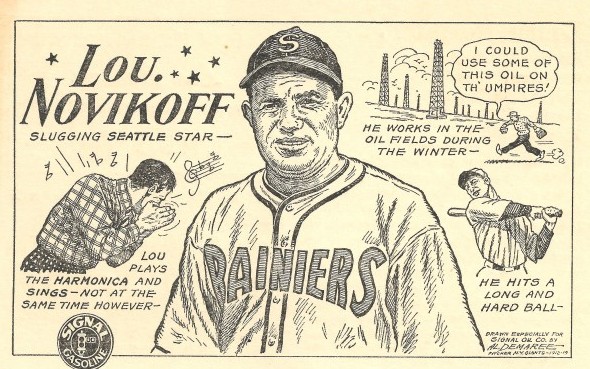

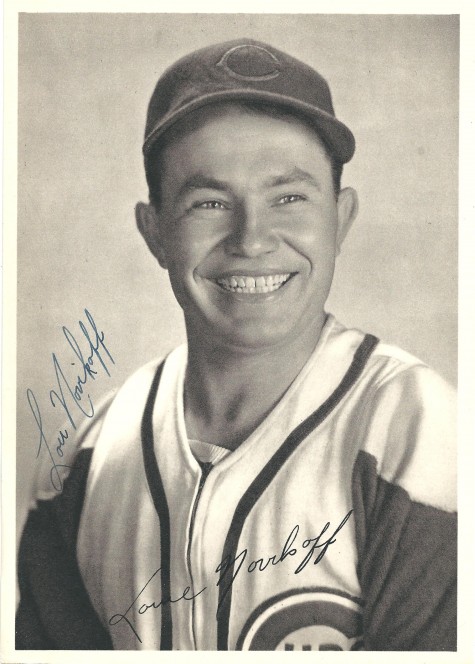

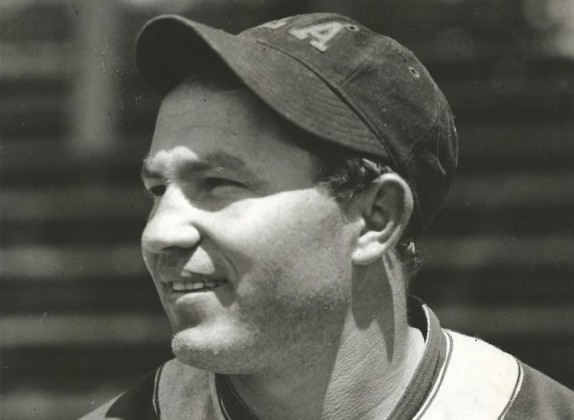

Newspapers splurged quarts of ink on the heavy-shouldered, moon-faced Novikoff, detailing his numerous superstitions, harmonica playing, impromptu singing, Russian-American heritage, bursts of temper, daily goofiness, popularity with young fans (he loved to give them practice balls, much to the annoyance of the Cubs), and bent for butchering batted balls to the outfield.

When Novikoff strolled into left field in Wrigley Stadium for the first time, he convinced himself that the ivy on the wall was poison ivy, and refused to go near it, thus diminishing his usefulness. Novikoff confided his fear of the ivy to reporters, who naturally made much of it.

According Warren Browns history of the Cubs, team trainer Bob Lewis finally took Novikoff to the vines one day and rubbed them all over his own body and chewed on a few to prove they were safe, at which point Novikoff had a question:

“Can I smoke this ivy?”

Novikoffs off-season pursuits fascinated Windy City reporters. Throughout his career, Novikoff worked as an oil-field roughneck, in the steel industry, and as a longshoreman based near Long Beach.

Reporters nicknamed Novikoff The Mad Russian when he played in the Pacific Coast League (The Mad Russian was a popular radio character in the 1930s played by Bert Gordon), and also described him as The Crazy Coassack, The Clouting Cossack, The Merry Muscovite, The Soviet Slugger, The Moscow Mauler, The Terrific Tartar, The Slugging Slav, and (one of our favorites) The Volga Batman, coined by Alex Schults of The Seattle Times.

Novikoff entertained reporters with colorful stories, displayed a story-worthy appetite (hot dogs by the dozen), and frequently trotted out his pet Russian wolfhound. Novikoff insisted the dog only ate Russian caviar.

Novikoffs main superstition, which he developed during his big season with the L.A. Angels (1940), centered around his belief that he could not perform well unless his wife, Esther, taunted him from the stands. Novikoff claimed Esthers bursts of derision inspired him to hit better.

So Novikoff planted Esther in a box seat at every home game he played, where she maintained a nasty running commentary, yelling You big bum! You cant hit!

When Novikoff went to Chicago late in 1941, he left Esther at home in Los Angeles. In the absence of Esthers taunts, Novikoff hit the aforementioned .241.

Esther moved to Chicago for the 1942 season and sat in a box seat behind the plate for the home opener against the Cincinnati Reds, and immediately launched into a tirade against her husband.

Strike the bum out! she chirped. He cant hit!

Novikoff got a base hit, and with Esther in the stands nearly every game, he went onto bat .300.

Novikoff possessed a fine baritone voice and believed that singing could change his luck when Esthers diatribes failed to do the job. Unfortunately for Novikoffs teammates, The Mad Russian loved to sing in the middle of the night on trains carrying the Cubs from city to city. Novikoff had a repertoire of ditties, but he clearly favored My Wild Irish Rose.”

(During a home-plate ceremony on Lou Novikoff Day at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles in 1940, an Angels public relations man handed Novikoff a microphone and asked him to address the crowd. Instead, Novikoff whipped out his harmonica and played it for a minute, then sang My Wild Irish Rose.)

Novikoff not only played his harmonica in the Cubs dugout, but also while playing left field, and might be the only major league player ever fined for singing.

In 1943, according to Daley, the Cubs lost a close game to the Phillies in Philadelphia. Chicagos manager, Charlie Grimm, an early-to-bed guy, liked to hit the sack before 10 p.m. (no night games then), but on this night couldnt get to sleep.

After tossing and turning, Grimm gave up and turned on the radio. The station was playing music from a nearby nightclub. Grimm didnt pay much attention until the master of ceremonies made an announcement.

Ladies and gentlemen, he intoned, we now will hear several songs from one of our guests here tonight, Lou Novikoff, the great Cubs outfielder.

Grimm jumped into his clothes and hailed a taxi, arriving at the nightclub in time to hear Novikoffs closing number, My Wild Irish Rose. After Novikoff finished, Grimm applauded politely and informed Novikoff that he had been fined for violating curfew.

Grimm told Daley that he did not have the heart to fine Novikoff when The Mad Russian made a spectacular steal of third base — with the bases full.

I couldnt resist, Novikoff told Grimm. I got such a beautiful jump on the pitcher.

For that, and a litany of other reasons, including his annual holdouts, Novikoff remained more or less a permanent member of the Cubs doghouse throughout his tenure with the team.

The Cubs dispatched Novikoff back to the Los Angeles Angels for the 1945 season, and he hit .310 in 101 games. That November, the Philadelphia Phillies, in a special draft of returning war-time players (Novikoff did a hitch in the Army), selected Novikoff, blocking an attempt by former Seattle owner Bill Klepper of the Portland Beavers to land The Mad Russian. Seven months later, the Phillies sold Novikoff to Seattle.

Following the sale, Novikoff told The Post-Intelligencer he might not report, saying that he thought he could make more money in the Mexican League. That didnt work out.

I didnt even get a nibble from the jumping beans, Novikoff told Seattle reporters when he arrived in town to join a Rainiers team en route to a 74-109 record.

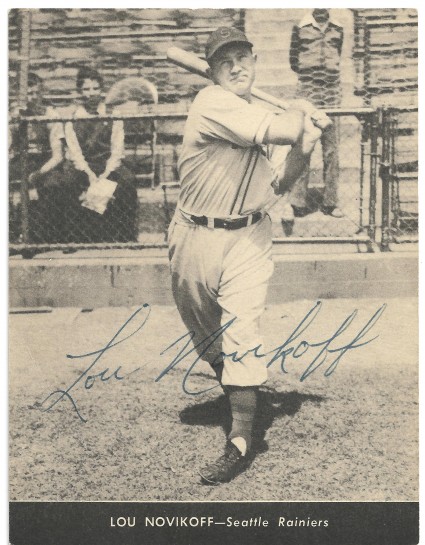

Most of the newspaper guys figured Novikoff would bang a lot of home runs for the Rainiers, as he had done for the 1940 Angels, but he hit just two in 84 games. Alex Schults of The Times, who could have been describing the current power outage at Safeco Field, explained why:

Sicks Stadium just isnt built for that kind of baseball, and putting a home-run hitter there and telling him to go for distance is much like entering a plow horse in the Longacres Mile. The fences arent too far away, but the heavy air that hangs in the bottom of the Rainier Valley just wont let a baseball get up and ride.

Novikoff batted .301 with 34 RBIs for the 1946 Rainiers, White generally using him in the third hole, just ahead of a rising youngster, Earl Torgeson. Novikoff had an otherwise uneventful first season with the club, except for two incidents described by Dan Raley in his excellent history of the Rainiers, Pitchers of Beer.

One day, after Novikoff was called out after sliding into second base, he delivered a fierce rant at the umpire. As Raley reported, “Spotting the image of another arbiter painted on the Sicks’ Stadium wall in an advertisement, one with outstretched arms signaling a positive outcome, Novikoff took off running toward it, slid in at the base of the endorsement on the warning track, turned to the real ump and bellowed, ‘See, I was safe, you sonofabitch!'”

Another time, Novikoff became irked at teammate Lou Tost and punched him out as the Rainiers were preparing to board a train in Portland for Seattle. Left with a black eye and broken teeth, the pitcher could not make his next scheduled start.

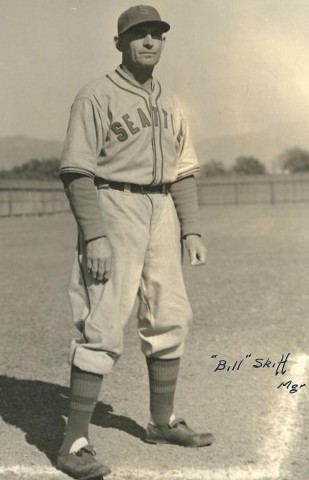

Novikoff hit .325 with 21 home runs and 114 RBIs in 171 games in 1947, and was hitting .327 after 64 contests in 1948 when, on July 6, GM Earl Sheely sold Novikoff to the Newark Bears (Yankees affiliate) of the International League in a straight-cash deal. Sheely made the trade with Bears manager Bill Skiff, who had skippered the Rainiers from 1941-46 before being replaced by White.

Kewpie Dick Barrett, the Rainiers ace, told The Times he was sorry to see the fun-loving Novikoff go, but not sorry to see his defense or lack of it leave the ball club.

I have two earned run averages, Barrett said. Theres the one which appears in the official records. The other one is the one I would have had if Novikoff had been in Russia. I told him, Please, Lou, just a little more reach on those fly balls. And run a little faster maybe. But Lou told me, Sometimes I just bog down out there.

When Novikoff joined the Angels, their great outfielder, Jigger Statz, tried to teach Novikoff how to play the field. But the lessons didnt take.

The Ballplayers, an encyclopedia of baseball biographies, described Novikoffs outfield misadventures this way: He had trouble locating fly balls, and would leap at a line drive and appear to wrestle it to the ground.

Noted The Associated Press: The rollicking Mad Russian, who played to the delight and dismay of fans and managers, made every catch in the outfield an adventure. Fans came just to see those efforts. There was a game at Wrigley Field. Ace pitcher Claude Passeau of the Cubs had a no-hitter going when the batter lofted an easy fly to Novikoff. Some say it fell in safe after conking Lou on the head. Others say no, it hit his shoulder. At any rate, Passeau lost the game when that hitter later scored.

Daley in The New York Times: No one ever accused Looie of being a second Tris Speaker, and often it was an even-money bet that a fly ball in his general direction would land on his head instead of his glove. Further, base runners confused him more than somewhat and things went blurry on him when enemy operatives scampered from sack to sack.

Emmett Watson in The Times: Novikoff had an unhappy faculty of losing more games with his fielding than he ever could win with this hitting. Hed play simple fly balls into triples and decapitate men in the dugout with his throws toward home plate. When Novikoff failed to make a crucial catch, the woe of the crowd was monumental. But there was poetic justice in the way he came to the plate, a couple of innings later, aching to redeem himself. Sometimes he did. Sometimes he didnt. He always had pitchers like Barrett ready for a psychiatrists couch.

Following a double header against Oakland July 11, 1946, Watson wrote, Last nights double bill with Oakland was played with characteristic Russian ambiguities, confusion and unilateral action. Novikoff had a hand in just about all the significant proceedings, including adding a few gray hairs to the head of manager White. Everything went wrong for Lou in the third inning of the nightcap. First he let a Texas Leaguer drop out of his hands in left field with Mickey Brunett trotting across the plate.

Skiff started off Novikoff not with his own Newark club, but with the Houston Buffs of the Texas League. The Pecan Park Eagle, a Texas blog describing one unidentified fan’s recollection of that team, wrote about Novikoffs signature moment:

In a game against Beaumont, Novikoff seized upon an opportunity to do something on a baseball field that I had never seen before or since. During a late-inning pitching change by Buffs manager Del Wilber, Novikoff left his position in left field to take a quick rest room break. Unaware of his departure, Wilber made his change on the mound and the home plate umpire gave the signal for the game to resume, with no one in left field for the Buffs!

Meanwhile, we Knothole Gangers are yelling back at the Buffs clubhouse: HURRY UP, LOU! THEYRE GETTING READY TO START THE GAME AGAIN WITHOUT YOU!’

All of a sudden, we see Lou Novikoff running out of the clubhouse, trying to fix and button his baseball pants as he runs back to the field. Hes saying something loud, something like, OHHH BOY! OHHH BOY!’

Unfortunately, Lou didnt make it. Before he could get back on the field, a Beaumont batter had banged a dunk liner into left field. By the time the Buff center fielder rushed over to pick it up, the very surprised Beaumont hitter had turned it into a two-run triple that would ultimately drive the nail into the Buffs coffin for the night.

The same Pecan Park Eagle blog also summarized what made Novikoff so appealing to fans.

He was one of the friendliest, funniest guys on the team. He seemed to like us kids. That kid-friendly quality always made a difference with us. And hey! Lou Novikoff was one of the few Buff players who would flick an occasional practice ball into our little campy cheap-seat section down the far left-field line near the home team clubhouse.

“Lou Novikoff was just one of those guys who made us kids feel we mattered. He did it with smiles, nods of the head in our direction, a few baseballs, and an occasional song by voice or harmonica tune from the field.

Two years after departing Seattle, Novikoff refused to take a $1,000 pay cut from Newark and moved to the Western International League, first with Yakima, then Victoria. At the end of the 1950 season, Novikoff retired from professional baseball and returned to fast-pitch softball with the Long Beach Nitehawks, a team he led to three International Softball Congress World Fast-Pitch championships. Novikoff played until he was 53 years old and entered the Softball Hall of Fame in 1965, the first man inducted.

Following Novikoffs death at age 55 from a heart attack Sept. 30, 1970, Arthur Daley wrote a column about him. It said, in part, When he came to the Cubs he had two commodities to sell, color and a reputation as a hitter. But when he left, his slugging reputation was damaged beyond repair. But he did supply a vivid splash of color when it was so sorely needed, and he was a genuine gate attraction when most of the real stars were off to war.

During his stay in Seattle, a Post-Intelligencer reporter asked Novikoff what would have happened if pitcher Novikoff ever had to face batter Novikoff.

I would have either braised me with a pitch or killed me with a line drive.

Figure that out at your leisure.

————————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Wednesday is one of my favorite days of the week, because I know I’ll get to read the latest edition of the Wayback Machine. Great stuff David.

Wednesday is one of my favorite days of the week, because I know I’ll get to read the latest edition of the Wayback Machine. Great stuff David.