By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Few athletes in Washington state sports history possessed the range of athletic skills that came so naturally to Sammy White (1927-91), who played major league baseball for 11 years, could have had careers in the NBA or on the Pro Bowlers tour, and wound up his life as a golf professional.

A potential involvement in pro basketball failed to pan out when, after a training camp tryout with George Mikan’s Minneapolis Lakers, the second-year club released White from his contract through no fault of White’s.

“If he’d stuck with it, he could have had a career in the NBA,” Dr. Jack Nichols told The Seattle Times in 1991. “He could have been a small forward. He was one of the first guys I ever saw who could float, like so many of the players do today. He was a floater before Johnny O’Brien and Elgin Baylor came along (see Wayback Machine: The Two Lives Of Elgin Baylor).”

“When he came to the University of Washington, Sammy was an instant star,” said Bob Tate, who played basketball and baseball with White and later coached championship basketball teams at Garfield High School. “He did things before anyone else did. He was just much more mobile than anyone else in those days. And, oh my gosh, he could hang in the air forever.”

Nichols had a more practiced eye for basketball talent than most. He played nine seasons in the NBA as a 6-foot-7 center with the Washington Capitols (1948-50) Tri-Cities Blackhawks (1950-51), Milwaukee Hawks (1952-54) and Boston Celtics (1954-58) following one of the more unusual college careers on record, highlighted by this: He is the only player in Pacific Coast Conference history named first-team all-league five times, including three times at Washington and twice at USC.

“Sammy probably could have played any sport professionally that he chose,” added Nichols, a teammate of White’s at Washington in 1947-48.

Born July 7, 1927 in Wenatchee, Sammy Charles White grew up in a one-room house on Aurora Avenue near Green Lake and attended Lincoln High School, where, as a 6-3 center, he first made a name for himself in basketball.

On March 17, 1945, White led Lincoln to the state championship, scoring 15 points in Lincoln’s 50-38 title-clinching victory over Bellingham at the Washington Athletic Pavilion (now Hec Edmundson Pavilion). White’s performance landed him at the center position on the All-State team, which included a future prominent college basketball coach, Jud Heathcote of South Kitsap.

Also an All-City baseball player, White announced he would attend Washington Aug. 16, 1946.

Before enrolling, White enlisted in the Navy and spent the 1946-47 basketball season playing for the Great Lakes Navy team. White joined the UW varsity a year later and became an immediate starter for coach Hec Edmundson (see Wayback Machine: Ace Coach Hec Edmundson).

White would have played his entire varsity career under Edmundson and his baseball career under Tubby Graves if athletic director Harvey Cassill hadn’t fired Edmundson after the 1947 season and Graves hadn’t retired. Those developments united White with one of the most versatile, if short-tenured, coaches in University of Washington history, and a man largely forgotten now.

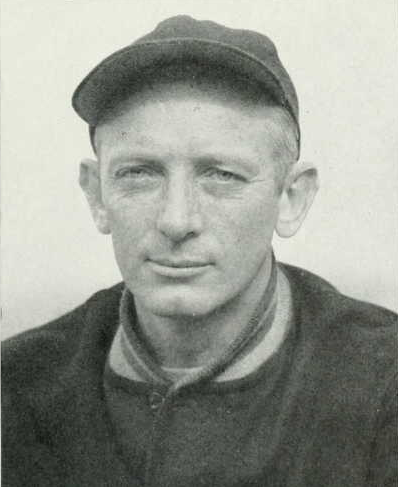

The Art McLarney saga started in the mid-1920s when he starred in football, basketball and baseball at Port Townsend High. Born Dec. 20, 1908 in Fort Worden, WA., to Irish-American immigrants Edward and Margaret McLarney, Art enrolled at Washington State in 1930 and became a two-time letter winner in both basketball and baseball.

During the 1931 baseball season, McLarney batted .320 and earned all-conference honors, and during the 1931-32 basketball season made the PCC all-star second team.

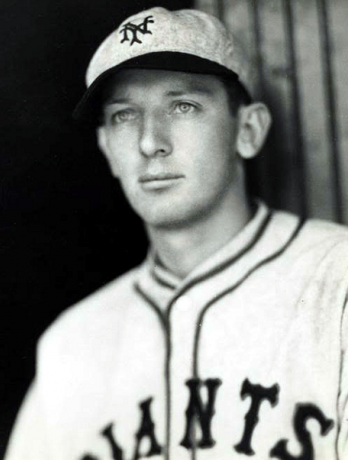

The New York Giants became so enamored with McLarney as a collegian that in early 1932 they signed him off the WSU campus, hoping he could hold down a roster spot that came available when future Hall of Famer Travis Jackson suffered a season-ending injury.

When McLarney signed with the Giants, the Associated Press wrote that McLarney was a “sensational shortstop, a brilliant fielder and a consistent hitter.” But in the nine games the Giants allotted him, McLarney never got much of a chance to prove it.

He hit .130 and in 1933 found himself with the Class A Williamsport Grays of the New York-Penn League. McLarney never received another major league shot, a common occurrence in an era when the majors had just 16 teams.

With the Grays, McLarney batted .237 with 32 hits, five doubles and one triple in 33 games and then signed with the AA Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League. In 86 games, he batted .268 with 85 hits, 12 doubles, one triple, and two home runs. Defensively, McLarney played all of his games at shortstop.

In 1934, McLarney re-signed with the Indians and, as a shortstop, second baseman and first baseman under George Burns and Dutch Ruether, batted .209 in what became his final season as a player (see Wayback Machine: Walter Ruether, ‘The Dutchman’).

McLarney went from the Indians to Bellingham, where he managed the city’s semipro team, a member of the Northwest League, for a year. Then he hooked on with Burlington High as head football, basketball and baseball coach, and moved to Cleveland High in the fall of 1938.

His first Eagles basketball team won two and lost 10. His next three teams went 9-7, 9-5 and 8-4, records that landed him a job at Roosevelt High, where in three seasons his Roughriders won 43 games, lost four, won city titles in 1944 and 1946 and the state championship in 1946.

The University of Washington brought McLarney aboard as an assistant football coach in 1946, assigned to work under Ralph (Pest) Welch. That winter, McLarney joined Edmundson’s basketball staff and the following spring assisted Graves with UW baseball.

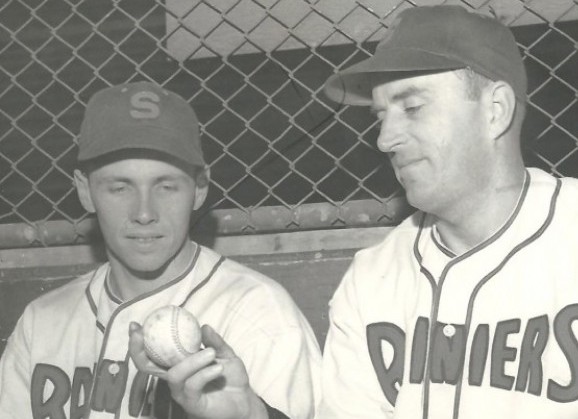

McLarney replaced Edmundson after Cassill fired the UW legend and took over for Graves when he retired. McLarney’s star pupil in both sports: Sammy White, more well known in basketball than baseball at the UW due to the Huskies’ hoop team’s higher profile and its successes in the Pacific Coast Conference and NCAA Tournament.

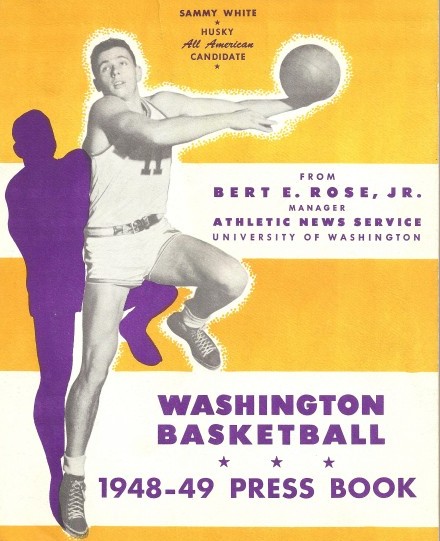

The PCC did not maintain official statistics in those days, but box scores show White averaged 12 to 14 points per game in an era when a 20-point scorer was rare. White’s best: 21 points in a 64-57 win at California in the 1948 PCC playoffs that sent the Huskies to the NCAA Tournament for just the second time in school history (first time 1943).

Playing alongside All-America Nichols, White also scored 15 points in a 59-42 victory over a Slats Gill Oregon State team that clinched the PCC’s 1948 Northern Division title. When the UW won for the first time in the NCAA Tournament, March 20, 1948 vs. Wyoming in Kansas City (57-47), White had 16 points.

White made second-team All-PCC Northern Division as a sophomore under Edmundson and first team in his junior and senior years under McLarney. In 1948, he also made first-team All-Coast on a club that included future Naismith Hall of Famers Bill Sharman and George Yardley.

“I was with Al Brightman when we were recruiting Elgin Baylor to play at Seattle U,” said Lew Morse, who played basketball with White at Washington and became a life-long friend. “He wasn’t as tall or muscular as Baylor, but he could do many of the same things.

“In many ways, he was Elgin Baylor before there was an Elgin Baylor. Royal Brougham (the late sports editor of the Post-Intelligencer) once called him, along with (UW football star) George Wilson and (Olympic swimmer) Helene Madison, the three greatest Seattle athletes of the century (see Wayback Machine: ‘Queen Helene Madison’).”

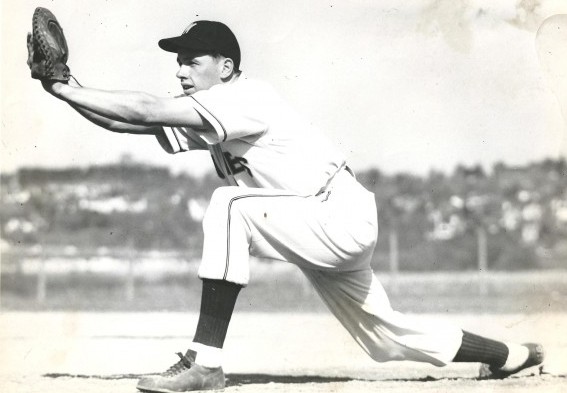

White also played baseball under McLarney in 1947 and 1948 and was the team’s leading hitter both years. White could have played the 1949 baseball season for Washington, but bowed out of the Huskies’ athletic picture following UW’s 54-41 basketball victory over Washington State March 5 in order to sign with the Seattle Rainiers.

“I’m a catcher,” White told The Seattle Times, “and catchers don’t break in as fast as guys playing other positions. I need experience. I’m 20 years old now, so I figured that the sooner I got started the quicker I’d move ahead.

“I’m tired of basketball. The first two years were fine. But it’s a hard grind, and it was getting to be work. I like baseball much better, but college baseball is no good – only 16 games a year.

“I figure to play professional basketball during the winter, if the right offer comes along. A couple of years of that, plus my salary as a baseball player, and I’ll make more money in two years than the average college graduate makes in ten.”

The UW couldn’t get too upset at White’s decision to bolt. Rabid Husky alum and booster Torchy Torrance (see Wayback Machine: Roscoe ‘Torchy’ Torrance), the Rainiers’ vice-president, signed White with the blessing of his close friend, UW athletic director Harvey Cassill.

As compensation for taking White, Torrance told Cassill that he had persuaded a promising football recruit to enroll at Washington. That player: Hugh McElhenny.

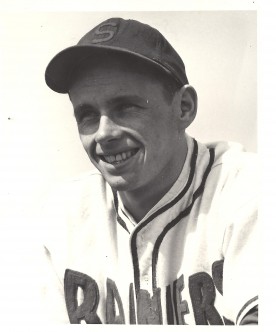

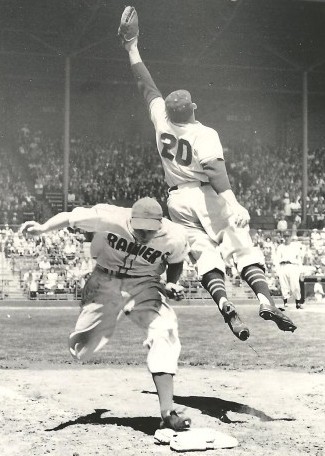

White made his Rainiers debut April 1, 1949, against the Los Angeles Angels at Wrigley Field. Replacing catcher Mickey Grasso in the second inning, White got his first Pacific Coast League hit by belting the ball directly over the 412-foot marker in dead enter.

By mid-May, White led the PCL with a .361 average, too good for the Boston Red Sox to ignore. They initially offered the Rainiers six players, valued at $75,000, for White, and the Rainiers accepted. The final deal: Seattle received pitchers Denny Galehouse, John McCall and John Hofmann, outfielder Neill Sheridan and cash for White, one of the biggest sales in Seattle franchise history. White had played a total of 29 games when the sale went through.

Under terms of the sale, White would remain with the Rainiers for the balance of the 1949 season and report to Boston’s spring training camp in 1950. But that plan didn’t last long. In July, the Red Sox transferred White to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association and, a month later, sent him to Class C Oneonta, NY., of the Canadian American League so that he could become an everyday player.

Following the 1949 season, the Minneapolis Lakers offered White a $5,500 one-year contract, contingent upon him making the team. White battled with Bud Grant, the future head coach of the Minnesota Vikings, for the final roster spot, but before the issue could be decided on the court the Red Sox stepped in and, fearing injury to their promising prospect, ordered White to give up hoops.

”It had to be one or the other and baseball offered the best opportunity,” White told Vince O’Keefe of The Times. “Besides, the Laker lineup would have been tough to crack. They had George Mikan, Jim Pollard, Slater Martin and Vern Mikkelsen (four future Hall of Famers).”

At about the time White reported to Boston’s spring training camp in 1950, McLarney resigned as head basketball and baseball coach at the University of Washington. Cassill attributed McLarney’s exit to “exhaustion” from attending the National Basketball Coaches Association meeting in New York, although Cassill never explained how a few meetings could be so exhausting.

“He was advised by his physician to give up coaching both basketball and baseball,” said Cassill.

The 43-year-old McLarney, with a 53-36 record and one NCAA Tournament appearance, actually couldn’t stand the stress of working under the tyrannical Cassill (see Wayback Machine: The Harvey Cassill Era).

“Reinvigorated” three months later after his escape from Cassill, McLarney surfaced as basketball coach at Bellarmine Prep in Tacoma (imagine a Division 1 head coaching stepping down today to coach preps). After that he coached basketball and baseball at the University of Portland and spent summers coaching the Pendleton Ranchers, a collegiate summer league baseball team.

As McLarney settled into his new job at Bellarmine Prep, White made his debut with the Red Sox (Sept. 29, 1951) as a late-season call-up from Scranton of the Eastern League. He stuck with the Red Sox out of spring training in 1952, and in 1953 had one of his best years, batting .273 with 64 RBIs and 13 home runs.

White also made the American League All-Star team, becoming the first of four athletes to make an MLB All-Star team and also play in the NCAA Tournament (also Ron Reed, Dave Winfield and Kenny Lofton).

“I can’t remember any player developing as fast as Sammy White,” his manager, Lou Boudreau, said after White became an All-Star. “Right now, I wouldn’t trade him for any catcher, and this includes Yogi Berra of the New York Yankees. I think Sammy will be another Bill Dickey, a right-handed Dickey.”

White didn’t turn out to be quite as gifted as Hall of Famer Dickey, but he developed into a solid defensive catcher with a good arm and the ability to get the most out of a Boston pitching staff that included Mel Parnell, Ellis Kinder, Bill Monbouquette, Mike Fornieles and Frank Sullivan.

“He steals more strikes from umpires than anyone else,” Yankees manager Casey Stengel said of White. “I’m not being critical. I’m just bowing to his skills.

White spent nine years as Boston’s regular catcher, and then went to Cleveland in a trade just before the start of the 1960 season. Instead of reporting to the Indians, White retired and used a year away from baseball to open “Sammy White’s Brighton Bowl,” which featured 18 lanes of both standard Ten-Pin and Candlepin bowling, the latter very popular in New England.

“Sammy White’s Brighton Bowl” became so popular that White opened a second bowling alley on the VFW Parkway near the Boston-Dedham line and a third called “Alpine Lanes,” a 10-pin establishment in Chelmsford, MA. White also became one of Boston’s most accomplished bowlers. He sported a 200 average.

“Sammy was good at whatever he was doing at the time,” Morse said. “He took up bowling and very nearly bowled a 300 game. He hit the ball all over the place in golf, but then he focused and got very good at that, too.”

(“Sammy White’s” is most remembered for an infamous quadruple murder that occurred there in 1980, long after White sold the place. “Sammy White’s” closed its doors in 1985.)

The Red Sox, who retained White’s rights throughout his “bowling” sabbatical, gave White his release in 1961. He played in 21 games for the 1961 Milwaukee Braves and finished his career with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1962 with a .262 lifetime average, 66 homers and 421 RBIs in 1,043 games.

White had four hits in a game 13 times, five RBIs in a game twice, and even brushed against history a few times.

On June 11, 1952, White ripped a ninth-inning grand slam off Satchel Paige at Fenway Park. After rounding third, White dropped to his knees, crawled to home and kissed the plate.

During a 4-for-6 effort June 18, 1953, White scored three times (two singles and a walk) in Boston’s 17-run seventh, becoming the only player of the 20th century to tally three runs in an inning.

In a game against Cleveland, May 1, 1955, White broke up Bob Feller’s no-hitter with a single in the seventh inning and, a year later (July 14, 1956), caught Mel Parnell’s no-hitter against the Chicago White Sox (Parnell managed the 1963 Seattle Rainiers).

McLarney held two jobs after leaving the University of Portland. In 1959, he was appointed recreational director of the Fort Worden Diagnostic and Treatment Center and then, through the efforts of former referee and friend Bobby Morris, he took a job in the King County Assessor’s Office. McLarney worked there until his retirement in 1967.

McLarney entered the Washington State University athletic Hall of Fame in 1981. He died Dec. 20, 1984, his 76th birthday, in Seattle and was buried at Laurel Grove Cemetery in Port Townsend.

After White sold his bowling alleys, he moved to Kauai, the northern-most island in the Hawaiian chain, with the aim of getting into the resort construction business with former Red Sox teammate Frank Sullivan.

The two helped develop Princeville-at Hanalei, a posh complex on the northern part of Kauai. White became so addicted – and proficient — at golf that Princeville-at-Hanalei’s board of directors hired him as its resident golf pro.

On Aug. 5, 1991, White spent most of the morning trimming hedges at his home, and then took a break to have lunch. White’s wife, Nancy, served him a chicken pot pie. The 64-year-old White was eating alone when he choked to death.

—————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

Dave: I remember at the time there were pretty reliable reports that McClarney was having serious drinking problems and that’s why Cassill fired him as the UW basketball coach. It turned out to be a great move with the arrival of Tippy Dye as the Huskies’ new coach, who turned Bob Houbregs into a superstar and led the UW closer to the NCAA championship in school history.