By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

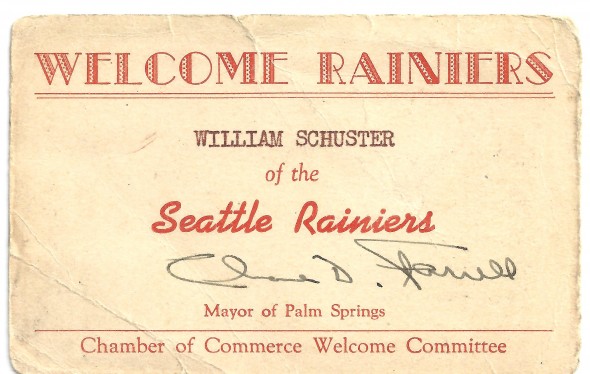

On a clear, spring morning in 1950, with the Seattle Rainiers ensconced at their preseason headquarters in Palm Springs, CA., new manager Paul Richards, neatly attired in freshly pressed slacks and a jacket, stood near the edge of the swimming pool at the Warm Sands Motel, chatting up player/coach Doc Cramer. Startled by a burst of loud yells and war hoops, Richards and Cramer quickly scanned the premises to discover the source.

Suddenly, a man, fully clothed, hurtled off a patio roof and cannonballed into the pool, the resulting chlorinated tidal wave washing over Richards and Cramer from head to foot.

As water streamed from their collars, lapels, pockets and cuffs, Richards and Cramer watched a jolly countenance bob to the pool’s surface.

“Stick around, Paul,” cannonball man said. “Next time I’ll do a jackknife.”

“Who the hell is that?” Cramer asked Richards.

“Schuster,” Richards replied, a scowl on his face. “Screwball Schuster.”

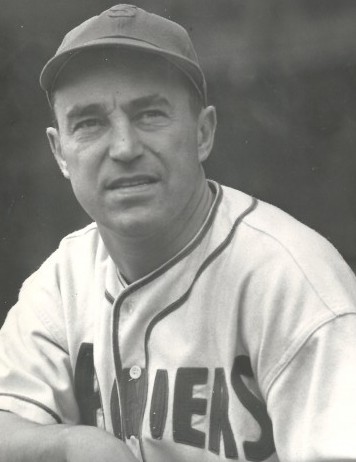

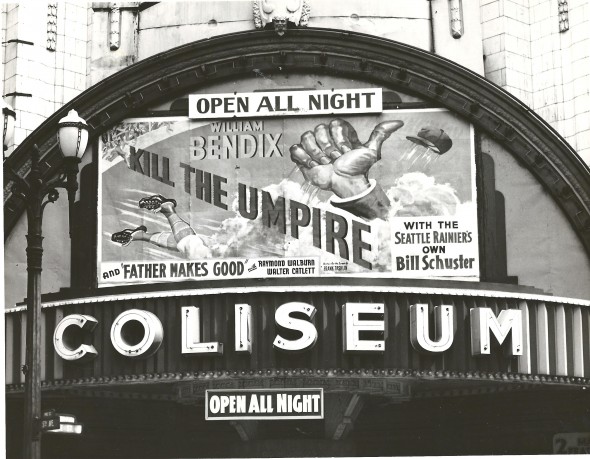

The Rainiers shortstop, Screwball Schuster vowed to discontinue his legendary clowning seven years earlier in 1943, making the announcement with an unofficial press release written on Los Angeles Angels stationary and several follow-up telephone calls to various sports editors in Pacific Coast League cities, including L.H. Gregory of The Oregonian, who bemoaned the imminent loss of baseball’s “last funny man.”

“We regret the announcement from Bill Schuster of the Angels that at age 34 he has decided to settle down, be a good boy and resist the temptation to clown on the field,” Gregory, a University of Washington graduate, wrote in his popular column. “He’s the last of the funny men in this league and baseball could stand a laugh or two in these serious days.

“The new tendency toward no fun and a serious attitude at all times has been noticeable for several years, especially in the training camps. Twenty years ago, every camp had at least one funny man; in the old days under Tom Turner, the Portland Beavers sometimes had two or three at once. To be funny in baseball is quite a gift.”

Gregory opined that the “retirement” of the Pacific Coast League’s last funny man merited a short review of the league’s legendary clowns, and he began with Walter Neils “Cuckoo” Christensen, who had a two-year (1929-30) stint with the Mission Reds, during which Cuckoo dazzled spectators with his favorite stunt: performing somersaults before he caught fly balls.

“One afternoon at Vaughn Street Park (Portland), while a Sunday game was held up by rain, Cuckoo kept 10,000 people laughing for 45 minutes and made the delay almost a pleasure,” Gregory reported.

Gregory next examined the flaky feats of Wes Schulmerich and Edwin Charles (Snake Charmer) Tomlin, noting that Schulmerich, an Oregon native who had been recruited by Knute Rockne to play football at Notre Dame, once was escorted off the field by a cop (part of his act) and later reappeared wearing the policeman’s clothes.

“We’re going to miss funny man Bill Schuster,” Gregory lamented. “No one clowned better.”

To the relief of Gregory and thousands of PCL fans, but to the consternation of numerous players and managers, Schuster’s vow to play it straight quickly became a false alarm.

Within mere days, Schuster had once again scaled the chicken-wire backstop at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, shot an umpire with a water pistol and dug another fox hole at home plate when a pitcher brushed him back.

Later that same year (1943), the Angels, for whom Schuster played — and starred — for seven years, held a “Bill Schuster Night” at Wrigley Field to salute their popular shortstop.

“The Angels honored Schuster at a late-season game in front of an announced crowd of 16,001,” Gregory wrote. “Believe it or nay, 8,000 cheered wildly, but the other 8,001 booed lustily.”

Gregory also reported on a game – no date disclosed — in which Schuster, after instigating a bench-clearing brawl, not only absorbed punches from Portland players, but from his own Angels’ teammates, who saw an opportunity to deliver a payback for his puckish pranks.

“The Angels saw it as their chance to finally get him,” said Gregory. “Schuster had that effect on people.”

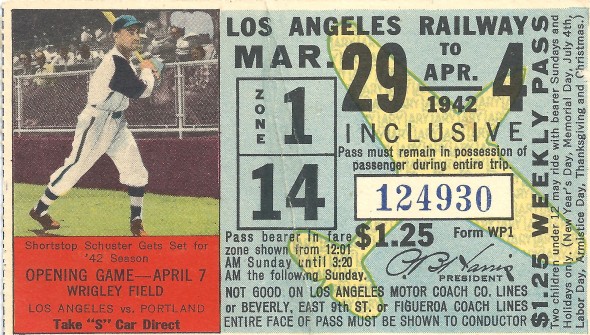

In an article prior to the start of the 1942 season, after the Angels acquired Schuster from the Rainiers, The Los Angeles Times went to some lengths to provide scouting reports on each player on that year’s Angels club. The Times analyzed the strength and weaknesses of individual batters and pitchers.

But the scouting report on Schuster said, “Schuster is a big league shortstop with a bush brain. He is noisy and offensive and probably the last person in the world to be wrecked with on a desert island. Yet he hits well and fields brilliantly, which is why he is always around.”

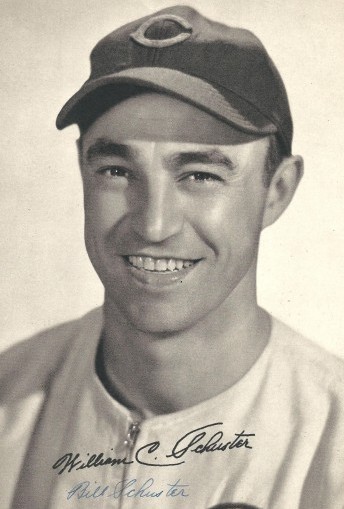

William Charles “Buffalo Bill” Schuster, so nicknamed because he was born Aug. 12, 1912 in Buffalo, NY., began his career in ebullient eccentricity in 1935 with Class A Scranton of the New York Penn League after attending the University of Buffalo, which also had another alum, Eddie Basinski, carve out a notable baseball career (see Wayback Machine: Eddie Basinski, ‘The Fiddler’).

Schuster spent two years (1935-36) in Scranton before his summons to the Pittsburgh Pirates, for whom the 25-year-old made his major league debut Sept. 29, 1937.

He didn’t last long, getting into only five games between 1937-39, sandwiched around a 103-game stint for the Class AA Montreal Royals of the International Leeague in 1938. In 1939, Schuster switched to the Tony Lazzeri-managed Toronto Maple Leafs, an affiliate of the Boston Bees (National League), who had acquired Schuster in a July 15 trade with the Pirates.

Although Schuster hit .263 in 135 games and showed potential as a defensive shortstop, the Bees released him. Detroit Tigers general manager Jack Zeller found out about the impending move and figured he could take advantage in order to return a favor to the Seattle Rainiers.

The favor had roots that dated to the sale of Fred Hutchinson to the Tigers in 1938. That’s when a friendship, if not a semi-official affiliation, between the Tigers and Rainiers started.

A year later, in the winter of 1939, the Tigers released, as part of a team-wide purge, catcher Buddy Hancken, who appeared in 71 games for the Rainiers. The Rainiers didn’t squawk, much less demand an immediate replacement, from Detroit as they might have done.

They simply asked to be reimbursed when the Tigers found a player they could spare. Zeller knew that Seattle needed a shortstop, so he put in a claim for Schuster as soon as the Bees (later the Braves) released him. When the deal closed, Zeller called Seattle manager Jack Lelivelt and told him had a shortstop available.

Lelivelt needed one, having just lost the great Alan Strange to the St. Louis Browns (see Wayback Machine: Rainiers Legend Alan Strange). It cost Lelivelt $5,000 to get Schuster in uniform.

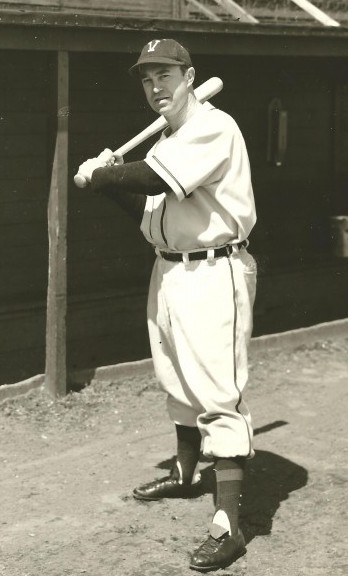

Schuster had a nice year for the 1940 pennant-winning Rainiers, hitting .291 with 188 hits, including 31 doubles and 74 RBIs in 176 games. But he drew more attention – good and bad – for his ballpark antics.

“In 1939, and 1940, we had great ball clubs under Lelivelt,” Seattle baseball icon Edo Vanni told The Vancouver News Herald in 1952. “Jack died suddenly in the winter of ’41 after winning two pennants. Some people said it was Schuster who drove Jack to an early grave, but I thought Lelivelt always handled Bill pretty well (see Wayback Machine: Jack Lelivelt’s Seattle Rainiers).

“Bill Skiff (Rainiers manager from 1941-46) inherited (from Lelivelt) a third great club in 1941, and though he’d been in baseball all his life, he apparently never ran across a man like Schuster. Skiff could never figure him out. There was a succession of events, prompted by Schuster, which made Skiff believe he was in a three-ring circus instead of a ballpark.

“It started one day in Hollywood when Schuster was on first base and Babe Herman, then in the twilight of his career, was holding the bag. There was a throw over to first and Herman dropped the ball. Before he was able to bend over and pick it up, Schuster had grabbed the thing, put it in his pocket and started running around the bases.

“As he reached home plate, he held up the ball for the umpire to see and chuckled, ‘See what I got, ump!’ The umpire didn’t appreciate the humor of it. He kicked Bill out.

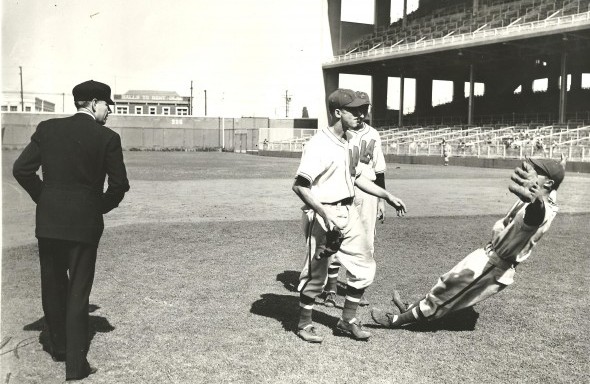

“A short while later, Schuster was sitting on our bench when we were at bat and there was a close play at the third. The umpire called the runner out, and Schuster leaped off the bench like a shot.

“He traveled in a straight line for the ump, then just before he got to him, slid at his feet. What Bill didn’t know, however, was the grass was wet, and when he slid, he took right off and dumped the umpire on his backside. The fellow had to go to hospital for three days, and Schuster was tossed out once more.

“Skiff was getting pretty impatient with all this, but he didn’t crack until one day, when we were leading by about 10 runs, Schuster hit an easy tap back to the mound. Then, instead of running for first, Bill lit out for third.

“I thought Skiff was going to drop with surprise. By the time Bill got close to the third base coaching box, Skiff had recovered. He told Bill he had better go all the way around because it was going to cost him $25, and he had better make it worthwhile.

“These things kept happening until Schuster had been tossed out of eight ball games in a row! It was probably a Pacific Coast League record. Pete Coscarart, our utility infielder, had played 12 games all year, and nine of them were for Schuster after he’d been ejected.

“On the ninth day, we built a terrific early lead. Schuster had been particularly docile and we figured he was going to break his streak of getting the thumb at eight in a row.

“In a way, I suppose you could say he did. He was in the on-deck batter’s circle late in the game when the umpire called a doubtful strike on the hitter. Schuster walked up to protest and got off a few hot words. He almost nearly warmed up, when Skiff arrived at the plate and tapped Schuster on the shoulder.

“’Bill,” he said, “’go on back to the dugout.”’

‘“I can’t, I’m up next,”’ Schuster protested. ‘“Did you see what this blind so-and-so called on us?”

‘“I saw everything,” Skiff squawked. “’Now go on back to the dugout. You’re not batting next.”

“‘Whaddya’ mean!” Schuster yelped. “’The ump hasn’t kicked me out.'”

‘“No, but I have,” Skiff grinned. “‘You’re going to get it from somebody pretty soon, so I might as well kick you out and fine you, too. That way we’ll keep the money in the family.

“Schuster was a real eccentric fellow.”

Skiff ultimately grew so weary of Schuster that midway through the 1941 season he sold him back to the Los Angeles Angels for $2,000, $3,000 less than Lelivelt spent to acquire him a year and a half earlier.

Over the next five and a half seasons, Schuster evolved into one of the best defensive shortstops in Pacific Coast League history. He hit between .262 and .298 every year, averaged 70 RBIs, helped lead the Angels to the 1943 and 1947 PCL championships and twice was named the Angels’ Most Valuable Player.

On Sept. 19, 1941, three months after the Angels acquired him from Seattle, Schuster became the third player in league history to steal three bases in one inning, a feat that included a swipe of home.

In 1943, he led the PCL in at-bats, runs scored and doubles, which earned him a 1944 promotion to the parent Chicago Cubs, for whom he hit .277 in 60 games. Schuster also got into 45 games for the 1945 Cubs, the last time they reached the World Series.

After returning to the Angels in 1946, Schuster played three and a half seasons, always performing at a high level while driving a succession of managers – Jigger Statz, Bill Sweeney and Bill Kelly – to various degrees of irritation.

“Something within Schuster stirred like a Geiger counter and before you knew it the imp in Schuster started to become radioactive,” said Sweeney.

Following a Rainiers game against the Los Angeles Angels Sept. 14, 1943, Alex Schults of The Seattle Times wrote, “Buffalo Bill Shuster, who had his ups and downs in Seattle baseball, definitely is Seattle’s Public Sports Enemy No. 1 from now on, after his display of rowdy baseball yesterday while the Rainiers were beating Los Angeles in the opening game of the Pacific Coast League’s President’s Cup series, 3-2.

“Schuster lot his last friend among Seattle fandom when he slid into the bag at second base in the eighth inning and then hopped to his feet, a full step inside the base lines, and knocked the wind out of the Rainiers’ Ford Mullen. While Mullen was stretched on the ground, Schuster ran for the dugout with Byron Speece and a couple of other Rainiers in pursuit.

“It’s a runner’s privilege to slide into a base as roughly as he wants, as the base paths belong to him. In fact, diamond etiquette even permits sliding across a base to hit an infielder trying to throw for a double play. But there’s no precedent that condones a runner who hops to his feet and steps inside the base lines to hit a fielder.

“Schuster has a bad habit of starting arguments and then letting someone else finish them. He led (catcher) Gilly Campbell into a fistic defeat at the hands of Al Niemiec a couple of years ago, just after Seattle had shunted Campbell and Buffalo Bill off to Los Angeles.

“Some of his madcap antics didn’t turn out so favorably for him, though. There was the time when Roy Joiner, the Hollywood southpaw, hung a kayo punch on Schuster and Bill woke up in the dressing room.”

After Sweeney, who managed the Rainiers in 1952-53, resigned as Angels manager, Bill Kelly replaced him. Not long into Kelly’s tenure, The Los Angeles Times said, “Schuster‘s spontaneity and effervescence act like a rasp on the naked ganglions of his managers, but Schuster was winning ball games and Kelly has no choice but to keep him and call frequently for a psychiatrist.

“When the name of Schuster is mentioned, Kelly’s face collapses into trembling folds of flesh and his temples throb visibly through his brown felt hat.”

Emmett Watson of The Times penned one of the more colorful scouting reports on Schuster, a k a “Broadway Bill” and “Schuster The Rooster,” when Schuster returned for a second go-around in Seattle in 1949 (Schuster liked to call himself a “futility infielder.”).

“There are a number of things Schuster may do for the Rainiers,” wrote Watson. “It is certain, before long, that he will climb the screen behind home plate like a monkey. He is bound to hit a pop fly and slide into the Rainier dugout. He is a cinch to get ‘knocked down’ by some pitchers and start scratching a hole in the batter’s box. These are fairly typical Schusterisms. There are others, which the 35-year-old shortstop will do in a pinch, such as:

“Bunt, hit and run, steal a base, argue with umpires, hit in the clutch, pull the hidden ball trick, and drive (manager) Jo Jo White crazy. All this only scratches the surface of the artist’s repertoire. Schuster is never one to stand still – he adds something new every week.

“But in the last analysis, Schuster can still play baseball the way Doubleday had it in mind. He is a bearing-down ball player and what the records don’t show is that Buffalo Bill scores his runs when you need them and gets his base hits when they help.”

On Sept. 3, 1949, shortly after his return to the Rainiers, Schuster belted two home runs in the fourth inning at Sicks’ Stadium in a win over Los Angeles.

But he also did these things: Against the San Francisco Seals, he got halfway up the first baseline on a ground ball, turned around, ran home and slid back into the plate when he recognized he would be a sure out at first. Against San Diego, he cut across the diamond instead of running into second on a sure double play. In a game against Portland, after being called out on a close play, Schuster pretended to faint.

“Billy Schuster was a wild man,” said Rainiers picher Paul Gregory. “But as long as he behaved and performed there wasn’t a problem.”

Schuster became manager Paul Richards’ problem in 1950, when Richards succeeded interim Bill Lawrence (see Wayback Machine: Bill Lawrence, Ol’ High Pockets).

“Richards’ reactions to Schuster ranged from thoughts of mere venom to out and out homicide,” said Seattle Times reporter Lenny Anderson. “Richards dreamed blissfully at night that the irrepressible infielder had been sold to the Vladivostok White Sox, only when he awoke Schuster was still on the roster. Schuster was needed, but Richards disagreed.

“As a result of their divergent views on this matter, a definite coolness developed between Schuster and Richards by May. By July, the Ice Age had arrived. Richards’ most triumphant moment came during the final week of the season when he was able to invite Schuster to depart and return nevermore.”

As he left Seattle for the final time as a player, Schuster said, “I was the most popular man on the club. One Seattle reporter shed tears on his typewriter.”

Author/researcher Dick Dobbins wrote one of the definitive histories on the Pacific Coast League. Published in 1999, The Grand Minor League is an oral account of the league’s history, ballparks, teams, owners, managers, umpires and rivalries. Only one individual rated an entire chapter: Bill Schuster.

Dobbins introduced Schuster by saying, “In the annuals of the Pacific Coast League, probably no one player is more remembered than Billy Schuster . . . Billy was a true flake but also a fine ballplayer. Other comics graced the PCL, but Schuster was more unpredictable than the rest. Umpires were victimized by him, managers couldn’t control him. Players didn’t know what to expect of him, and the fans loved him.”

Eddie Basinski, who spent time with the Rainiers, recalled for The Grand Minor League an incident that occurred when he played for Portland and Schuster for Los Angeles.

“You know, that dirty rat, when I joined the Portland club and we were in Los Angeles, I was his seventh hidden-ball-trick victim. And this was my friend! We were both from Buffalo. I hit a double, and he’s talking to me about Warren Spahn (a childhood friend of Basinski’s) and all of a sudden he’s standing next to me and says, ‘Hey, Ed, look what I’ve got.’ He said, ‘Why don’t you make a dive for the ball and we’ll make it look good.’ I said, ‘Like hell.’ So he hit me on top of the head. I could have killed Schuster that day, the dirty rat.”

“When I was with Sacramento, one night Schuster is batting against me at Wrigley Field,” said long-time PCL pitcher Bud Beasley. “I throw over to first base five times trying to pick the base runner off. The next thing I realize, Billy is standing next to first base, with bat at the ready, waiting for me to ‘pitch’ the ball to first base again.”

“He used to eat garlic,” said Rugger Ardizola, who played for the Hollywood Stars. “Then he’d challenge the umpire and, geez, the umpire would retreat, shaking his head, and Billy’s laughing like hell.”

“Kewpie Barrett was a good friend of Bill’s,” said Red Adams of the Angels. “Kewpie knew all of Bill’s tricks. Bill hits one back to the mound and Kewpie gets the ball and is nonchalant with it. He looks up and here’s Bill running at him. Well, Kewpie throws the ball in the direction of first and starts running as fast as he can toward the outfield with Schuster in pursuit.”

“One night in Hollywood, Roy Joiner was pitching in the ninth,” recalled Eddie Erautt of the Hollywood Stars. “Schuster tried to drag-bunt one. Joiner threw him out, and when Billy crossed the mound on his way back to the dugout, Roy was waiting for him. He busted him right in the mouth, laid him out cold! Schuster was laying on the mound. The game ends, the groundskeepers are turning out the lights. Schuster was the only guy out there.”

After Schuster retired as a full-time active player, with a career batting average of .279 and 63 home runs in 16 minor league seasons, he managed the Vancouver Calipanos of the Western International League for two years, and then returned to coach at Seattle under manager Jerry Priddy. Schuster worked third base, opposite a moonlighting Seattle U. basketball head man Al Brightman, who coached first base (see Wayback Machine: Odd Saga Of Al Brightman).

After Fred Hutchinson replaced Priddy in 1955, the Rainiers released Schuster from his coaching contract in order to give Hutchinson a chance to pick his own coach. Schuster did some scouting and eventually secured employment in the press room at The Los Angeles Times. He also worked in a gas station in Woodland Hills, CA.

William Charles Schuster died of a heart attack June 28, 1987 in El Monte, CA., at 74.

“The guy was sort of crazy,” said former Rainiers pitcher Paul Gregory. “But I wouldn’t mind having him on my club.”

———————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

I remember when I was a kid watching a rainier game where a runner was hit in the head near the shortstop position. When Schuster the Rooster took the field, he brought a broom out to sweep the spot where the runner went down. He brought down the house.