By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

By 1959, Dewey Soriano, a one-time Civic Stadium peanut vendor, had amassed a remarkable baseball portfolio. It included a decade as a minor league pitcher of distinction, his successful ownership and presidency of the Yakima Bears of the Western International League, and his stints as general manager of the Vancouver Capilanos and Seattle Rainiers. But Dewey the doer had only just begun.

When life-long friend Fred Hutchinson made his second return to the Rainiers in 1959, Soriano resigned his GM position in order to become executive vice-president of the Pacific Coast League. Just one year later, PCL owners elected him league president, succeeding Leslie O’Connor.

During his presidency (1960-68), Soriano played a major role in the PCL’s 1961 expansion to Hawaii and its bloat to 10 clubs in 1963 and to 12 in 1964, when the league moved east as far as Indianapolis.

Soriano also helped effect a number of rule changes, including the enforcement of a 20-second pitching rule designed to speed up games.

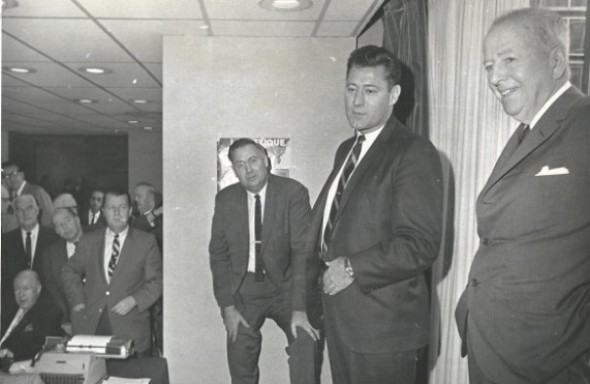

Bob Reynolds, owner of the California Angels, thought enough of Soriano’s work that in 1965 he nominated the Franklin High School graduate to succeed Ford Frick as major league commissioner. Gabe Paul, owner of the Cleveland Indians, also sponsored Soriano’s nomination.

After the commissioner’s job oddly went to former military man William Eckert, who infamously admitted after he entered office that he hadn’t seen a baseball game in 10 years, Soriano remained as PCL president while also working on his primary agenda: securing a major league franchise for Seattle.

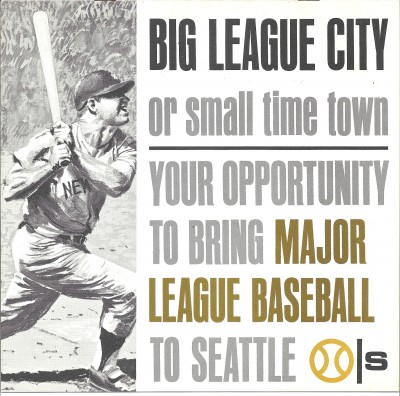

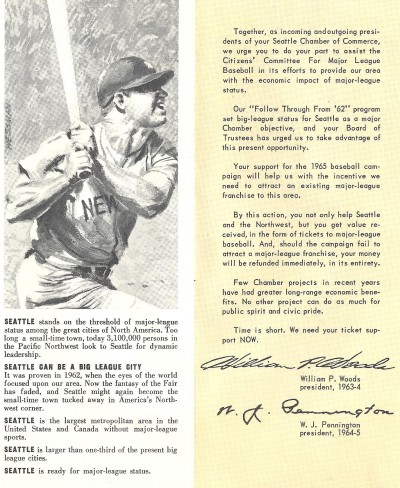

Soriano launched lobbying efforts in the mid-1960s, using his clout and connections as PCL president, and was aided by Major League Baseball’s announced plans to add four expansion franchises by 1971. Soriano’s self-appointed mission: make sure Seattle became one of the four cities selected.

Soriano’s principal argument on Seattle’s behalf, apart from the fact that Boeing airplanes would greatly reduce the travel distance to other major league cities, was that in the 20 years between 1937-57, Seattle led the Pacific Coast League in baseball attendance with 6.6 million customers.

Los Angeles, Dewey enjoyed pointing out, drew 6,317,000 and San Francisco 6,011,000 over the same period. Both became major league cities in 1958 when the Dodgers and Giants abandoned New York for the West Coast.

Soriano received help in his efforts from Washington senators Warren G. Magnuson and Henry “Scoop” Jackson, both of whom threatened to push legislation to eliminate baseball’s anti-trust exemption if Seattle didn’t receive a team.

Another senator, Stuart Symington of Missouri, made a larger impact on MLB’s expansion timeline when he, like Magnuson and Jackson, threatened to strip baseball of its anti-trust exemption if Kansas City did not get a team.

Unlike Magnuson and Jackson, Symington insisted that Kansas City receive a franchise immediately as compensation for the Athletics’ relocation to Oakland.

Cowed by Symington’s clout, MLB moved the expansion timeline from 1971 to 1969.

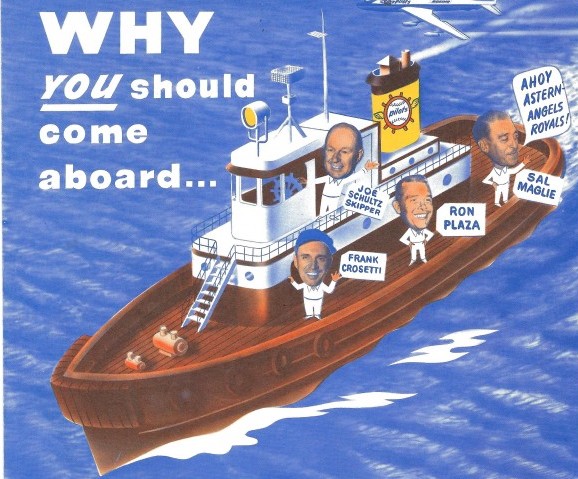

Soriano and brother Max, representing Pacific Northwest Sports Inc., made their first major move toward receiving an expansion club Oct. 23, 1966, when they purchased the Seattle Angels of the PCL from the parent California Angels.

The purchase not only gave Pacific Northwest Inc. a Triple A start toward a major league farm system, it also helped the American League solidify itself in Seattle, a city also coveted by the National League.

Next came a major push by the American League in which its president, Joe Cronin, and notable players such as Mickey Mantle, Carl Yastremski and Jimmy Piersall visited Seattle to urge voters to approve the construction of a domed stadium.

Cronin, Mantle, et al, impressed upon voters that if they said yes to a domed stadium, a major league team would be theirs (this campaign would become the key to Seattle’s subsequent suit in 1972 against the American League).

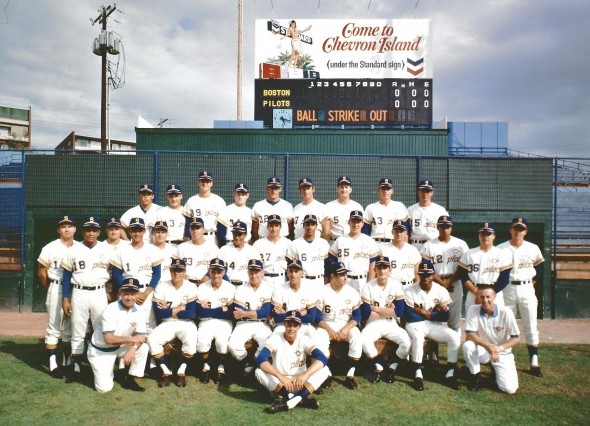

Slightly more than a year before Dewey officially stepped down as PCL Commissioner — April 8, 1969, when the new Seattle Pilots played their first game — the American League, meeting in Mexico City, awarded Seattle an expansion franchise to go with those presented to Kansas City, San Diego and Montreal.

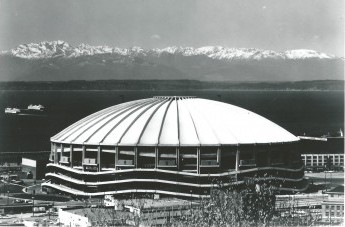

Seattle’s franchise came with conditions that initially did not appear to be daunting. In exchange for its team, Seattle would have to build a domed stadium – Dewey’s idea – to replace an aging and inadequate Sicks’ Stadium by no later than 1972 (King County voters, as part of series of bond prosposals called Forward Thrust, said yes Feb. 13, 1968).

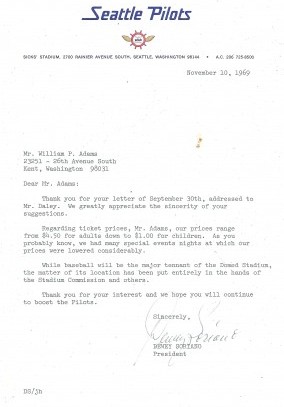

In addition, the City of Seattle would have to fund a major refurbishment of Sicks’ Stadium for the team’s interim use, principally increasing its capacity from 12,000 to 30,000 (the city allocated nearly $700,000 to make this happen) and adding amenities such as more bathrooms.

Hardly wealthy, the Soriano brothers nevertheless managed to scrounge up $2 million in front money toward the purchase price, most of it in Max’s name, as Dewey was going through a divorce at the time (he had been married to Alice Brougham, daughter of Seattle Post-Intelligencer sports columnist Royal Brougham).

Along with the Kansas City Royals, the Pilots faced an embargo by the American League, which would prove draconian: They would not be able to receive a share of the league’s television revenues for the 1969, 1970 and 1971 seasons.

That worked out to $2,062,500. In exchange for this concession, the Royals and Soriano brothers had to pay only a $100,000 expansion franchise fee.

If it had only been that simple. In addition to the expansion fee, the Seattle franchise had to pay $175,000 each for the 30 players they would receive from other American League teams to stock the club.

Subtract national TV revenues, and the team’s start-up costs came to $7.3 million. That didn’t include an operating budget.

Even with those handicaps, it elated Dewey Soriano that and he and Max had been able to bring major league baseball to their adopted home town (the Soriano clan, including father Angel, mother Anna and 10 Soriano children, moved to Seattle when Dewey was six years old).

“I was happy as heck,” Soriano told The Associated Press. “You don’t sleep very much, I’ll tell you that, because you want to get going and you want to get players that can really help your club.”

The Soriano brothers seemed perfect candidates to run the franchise. Dewey had more than 20 years of baseball experience at all levels of the game while brother Max had pitched for the University of Washington and, during his brother’s PCL presidency, served as the league’s legal counsel.

The Sorianos were missing just one thing: enough money to adequately operate the franchise.

Dewey, though, had become acquainted with William R. Daley, a former owner of the Cleveland Indians (1956-62), when Daley, in 1965, seriously considered moving the Indians to Seattle.

Cleveland city officials eventually made it worth Daley’s while to keep the franchise in Ohio, but Daley had remained intrigued about the possibility of owning a major league baseball team in Seattle.

Ultimately, Dewey and Max sold Daley a 47 percent stake in the team. The Soriano brothers kept a percentage and Dewey retained the team presidency.

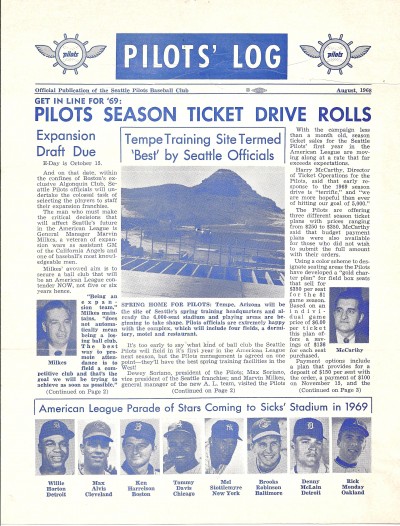

Things immediately headed south. The city of Seattle promised to expand Sicks’ Stadium from 14,933 to 25,000 seats for the opening home game against the Chicago White Sox April 8, 1969. But construction fell behind, and the city was unable to install all the new seats until June.

“When the season opened, we had season tickets printed for all 25,000, but couldn’t sell them because they didn’t exist,” Soriano said in recalling the event years after the city’s fiasco.

The fate of the Pilots, Soriano believed, may have been sealed before Opening Day. That’s when some of the “biggest people in the state” according to Soriano, told Daly, a Cleveland industrialist, “that they were not interested in investing in the ball club.”

Daly attended the opener, a 7-0 win over the White Sox, but went away shaking his head over the lack of amenities at the Depression-era stadium, not the least of which was low water pressure that made it virtually impossible to flush toilets during games that drew large crowds.

“I’ve never told anybody this,” Soriano said in a 1979 interview with The Associated Press, “but Daly wanted to leave Seattle as soon as the first game ended. I was just sick.”

A couple of months into the 1969 season, the club’s bookkeepers ran financial projections which showed that not only were the Pilots not turning a profit, but that Daley would likely have to invest considerably more to keep them afloat. When Daley saw those numbers, he cooled on Seattle even more.

“Sure, he had the money to do so,” Max told The Associated Press, “but I don’t think he was a careless person with his dollars. I think he looked at it as the odds being too much against Seattle being a viable franchise until a new stadium was built, and he didn’t know how long that was going to take.”

Not only did the Pilots not receive a share of national TV revenues, they had no local TV money, either.

“The cost of the AT&T line was such that we couldn’t get advertisers to come forth,” Max Soriano added. “There wasn’t any revenue for the ball club by the time you paid the telephone charges for a broadcast line.”

Competitively, the Pilots made their first goof on April Fool’s Day, 1969, when they swapped promising rookie outfielder Lou Piniella to Kansas City for a pair of prospects. Piniella hit .282 with 11 home runs and 68 RBIs and was named American League Rookie of he Year.

Otherwise stocked largely with castoffs and rejects, the Pilots stumbled on the field, going 7-11 over their first month. But they posted a break-even May (14-14), stayed with striking distance of .500 for the first three months, and were just six games back of the division lead as late as June 28.

But a disastrous month of July, when the Pilots went 9-20, and a worse August (6-22), ended any hope of contention.

A few Pilots players distinguished themselves. Tommy Harper led the American League with 73 stolen bases (most since Ty Cobb’s 96 in 15), a remarkable total given that he batted just .235 and had an on-base percentage of .349.

Don Mincher belted 25 home runs and made the All-Star team, and reliever Diego Segui, who would become the first starting pitcher in Mariners history April 6, 1977, had a 12-6 record with a respectable 3.35 ERA.

The Pilots produced a few highlights, most notably on May 16 when they combined with Boston Red Sox for a major league record 11 runs in the 11thinning. After the Pilots scored six, they surrendered five, but hung on for a 10-9 win. Typical of the Pilots’ luck, the excitement came at Fenway Park, not Sicks’ Stadium.

So the season ended with no starting pitcher sporting an ERA below 4.00, with only two Pilots regulars, Tommy Davis and Steve Hovley, featuring batting averages above .250, and with shortstop Ray Oyler checking in at .165 (see Wayback Machine: Seattle’s Woodless Wonders).

Had it not been for knuckleball-throwing relief pitcher Jim Bouton, who maintained a diary that would become the all-time sports best seller Ball Four, Gene Brabender, Don Mincher, Mike Hegan, Dooley Womack and the 1969 Pilots would have faded into oblivion.

In early September, with the Pilots en route to 98 losses, Daley reached for his gun and informed Seattle fans that they had one more year to prove themselves or lose the team. The threat backfired, attendance plummeted the rest of the season, Daley elected not to put more money into the club, and the Sorianos simply couldn’t afford to.

Pilots’ creditors, mum much of the season, started to get itchy about the money they were owed by Pilots management. Further adding to the misery of the Sorianos, a series of lawsuits delayed construction of the domed stadium.

Enter Fred Danz. A Garfield graduate who owned movie theaters, bowling alleys, radio stations and restaurants, Danz inserted himself into the Pilots’ mess, agreeing to buy the team from Daley and the Soriano brothers.

Major League Baseball happily approved the sale, but it fell through when the Bank of California demanded immediate payment in full on a $4 million loan it had made to the Pilots. Danz couldn’t come up with that money in addition to the $10 million he’d already raised to purchase the franchise, so the sale was nullified.

With a sale to Danz dead, Westin Hotels president Eddie Carlson, who had been a principal figure in the 1962 World’s Fair, cobbled together a non-profit corporation to buy the Pilots, but American League owners voted against accepting its offer, stating that it was a “for-profit” business and a non-profit franchise had no place in the league.

Both Magnuson and Jackson pressured the American League to reconsider, but by the time it did, Carlson’s group had disbanded.

With the club hemorrhaging $12,500 per day and no financial institution willing to bankroll it, the Soriano brothers were forced into bankruptcy.

“The club was without funds and it was impossible to borrow money,” Max Soriano told an adjudicator.

The Sorianos couldn’t hold out financially until the Kingdome was finished, so out of financial desperation they cut a deal to sell the franchise to a Milwaukee-based group led by future baseball commissioner Bud Selig. However, legal action dragged out throughout the 1969-1970 offseason.

The official transfer occurred April 14, 1970, just days before the start of the regular season, and carried a purchase price of $10.8 million. The move left behind angry season ticket holders and another flurry of lawsuits.

“I really felt they (the Pilots) would go, and I was bitter because we weren’t successful. But I made certain mistakes and must take the blame for them,” said Dewey, who maintained an enduring image of the 1969 season for the rest of his life.

“I’d see the people line up for the portable toilets – it was awful. Oh, the city did put in a new water main, but not until Oct. 15 – and the season ended Oct. 1.”

Soriano didn’t provide his side of the sordid story until six years after the Pilots had become the Brewers.

“When the club was sold, people wondered why I didn’t tell my side of it. I just felt too bad, I guess,” said Soriano, who said that the loss of the club cost him many of his friends.

Once celebrated for their ingenuity in acquiring the club, the Soriano brothers were pilloried for the subsequent shipwreck, although it was certainly not all their fault, unless a lack of wealth is considered a fault.

One – or perhaps some – critics draped at least two effigies of the Sorianos in public places, one in Pioneer Square, the other from a ramp leading to the Seattle monorail station. That effigy had a sign pinned to it that said, “Thanks Max and Dewey.”

The loss of the Pilots hit the Soriano brothers hard. Dewey’s daughter, Cathi, recalls that the family had to change its telephone number “because we were getting all these harassing phone calls. For that (the Pilots) to fall apart so quickly was a horrible thing for him.

“He was a poor kid from the Rainier Valley whose dream was baseball. That was his big goal — baseball, baseball, baseball. Bringing a team to Seattle was pretty amazing. I wouldn’t use the word bitter to describe how he felt. I would use disappointment. I’m not sure he ever got over it.”

Max and Dewey fairly faded from public view after the Pilots relocated. Both returned to nautical ventures, Max specializing in admiralty law, Dewey working as a Puget Sound harbor pilot (he ultimately had two stints as president of the Puget Sound Pilots).

The Sorianos received a measure of vindication when the state, county and city collectively sued the American League over the abrupt loss of the Pilots after just one season. Attorney William Dwyer presented such a compelling case during arguments at the Snohomish County Courthouse in Everett in January of 1976, that the American League simply caved in mid-trial.

It had no choice. Dwyer showed beyond reasonable doubt that the American League had a nefarious agenda to move the Pilots regardless of how they played or how many fans they drew. In other words, the Pilots were doomed no matter what the Soriano brothers did.

The settlements resulted in the creation of the Seattle Mariners with a 20-year lease (see Wayback Machine: Dwyer KO’s American League).

Dewey attended some Mariners games when they team began play in 1977, but he always remained in the background.

“He was supportive of baseball,” Cathi said. “But he knew it was over for him. He had been a big guy in town and he wasn’t anymore.”

Dewey and brother Max had a falling out after the Pilots left for Milwaukee, but ultimately reconciled their differences during a trip to Denmark, their mother’s homeland.

In the mid-1990s, Dewey was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. When he could no longer live alone, he lived with Cathi for a year and a half and then was placed in an assisted-living facility.

“The last person he recognized was his older brother, Amigo,” said Cathi.

Dewey Soriano, inexorably linked with Seattle’s baseball history, died April 6, 1998.

“I think history has been kinder to Max and Dewey for bringing the Pilots and for trying to get them started,” Larry Soriano, Max’s son, said after Dewey’s death. “They were ahead of their time.”

Also see Wayback Machine: Dewey Soriano Story, Part 1

——————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

6 Comments

This writing, week-in-week-out, is so far above, in substance, anything being put out locally, and perhaps even nationally, that it really should be receiving, or at least be nominated, for various journalistic awards. Furthermore, when one considers the efforts put into this for probably low remuneration, if perhaps any in the big picture, given the start-up nature of Sportspress Northwest, it really is impressive. I

I agree with you 100% – couldn’t have said it better. Many of David’s articles are from the time of my dad’s youth, and whenever dad reads an article, it brings out his own memories, allowing me to learn a lot more about my dad.

We’ve been doing the Wayback feature for a couple of years. By the time we sign off, we hope you’ll know — an appreciate — your dad really, really well. Thanks so much!

David and I sincerely thank you for your feedback. It is most kind and greatly appreciated (we can afford a latte, but lunch at the Metropolitan Grill is definitely out).

I love the Wayback Machine articles. Finding out what was going on behind the scenes during days of yore is truly fascinating.

David and I appreciate your feedback!