By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

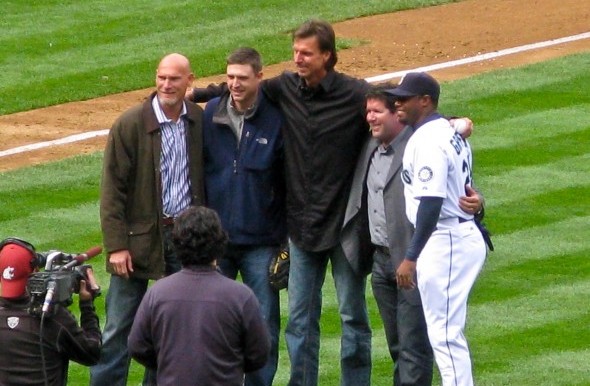

Saturday, Ken Griffey Jr. will join Alvin Davis (1997), Dave Niehaus (2000), Jay Buhner (2004), Edgar Martinez (2007), Randy Johnson (2012) and Dan Wilson (2012) in the Mariners Hall of Fame. Griffey’s induction ceremony will be prior to the 6:10 p.m. scheduled first pitch against the Milwaukee Brewers.

Each member of the Mariners Hall of Fame carved his own mark of distinction on the 37-year-old franchise, Davis as the club’s first star performer, Niehaus through a distinctive broadcasting style that endeared him to hundreds of thousands, Buhner with his home run prowess, defensive skills in right field and popular “Buzz Cut Nights.”

No inductee counts as many adulators as Martinez, who produced the most important hit in Seattle’s pro baseball history and has a street (Edgar Martinez Way) near Safeco Field and an award (Edgar Martinez Designated Hitter Award) named in his honor to prove it.

No Mariners pitcher wowed the way The Big Unit did, nor won a bigger ball game, a 1995 elimination contest against the California Angels that sent the Mariners to the postseason for the first time. Johnson’s battery mate that day when Johnson delivered a 12-strikeout, complete-game, 9-1 win over the Angels: fellow Hall of Famer Dan Wilson, who chipped in two RBIs in the win.

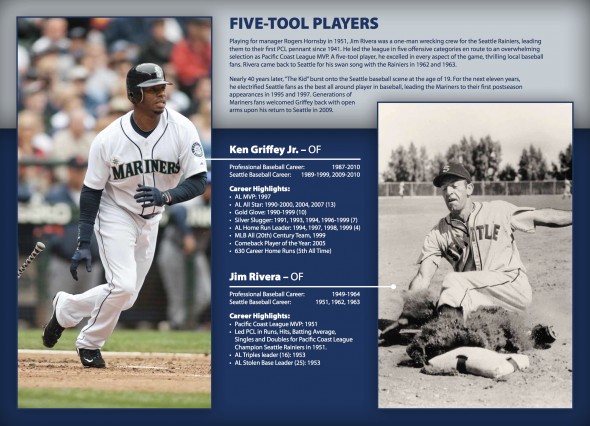

Griffey will be the greatest player to enter the Mariners Hall of Fame and the most significant individual it will ever induct. Where his six predecessors were all game changers, Griffey was both franchise changer and savior.

Mariners history is divided into two parts, before Griffey and after Griffey. The before Griffey part spanned a 12-year dark age (1977-88) in which the conversation was not so much about baseball, but about whether baseball would – or even could – survive in Seattle. After Griffey, baseball’s survival was never a point of debate, simply a fact taken for granted.

Griffey is responsible not only for changing the conversation, but the culture surrounding the team. To grasp how, it’s important to revisit those dark ages, which commenced not in the inaugural year of 1977, when the Good Ship Mariner set sail, but in 1981, when California real estate developer George Argyros purchased the franchise from the original ownership group, headed by entertainer Danny Kaye.

Argyros paid $10.8 million to acquire an 80 percent stake in the club and did so with an overriding aim: to dramatically increase the value of his investment. To accomplish this, Argyros followed a plan his bankers found spectacular, but all who loved the crack of the bat and yearned for a pennant race deemed abominable.

Steve Matt, a Dallas attorney, best summarized Argyros’ stewardship in late 1987, when the value of Argyros’ investment had soared to $56.8 million — $43.2 million more than he had paid for it seven years earlier.

“When you win a championship in a small market, your players end up demanding larger salaries and you end up having to pay them more,” Matt said. “Then the next year they finish in the middle of the pack, attendance drops off, you’re locked into higher payroll and suddenly the profit picture changes dramatically. Success in baseball can be a mixed blessing from the standpoint of profitability.

“They (the Mariners) have kept their payroll down so that it made sense in terms of the market they’re in. They’ve held the line on guaranteed contracts. And they’ve controlled their deferred-compensation liability. Those are three of the key things that contributed to making the value of the Mariners as high as it is. They are a remarkably well-managed operation.”

Well managed, perhaps, in a business sense, but the baseball was pathetic. Under Argyros’ thumb, the Mariners existed as an unpalatable mash of over-the-hill journeymen and not-ready-for-prime time youngsters. While the roster may have made economic sense, it never made competitive sense, the principal reason potential customers avoided the product.

Argyros constantly bad-mouthed his team, doing so while wringing lease concessions out of King County taxpayers. He succeeded, at one point receiving $19.6 million in givebacks, and also succeeded in having a clause inserted into the lease stating that if the Mariners failed to reach certain attendance goals he had the power to move the ball club.

Argyros’ teams, never in contention, had no chance of drawing the necessary throngs to keep him from triggering the escape clause, and so what few Mariners fans there were lived in a state of angst. Argyros loved using threat as a weapon, but it skewed the town’s appreciation for the game. It became gallows sport to speculate on the team’s ultimate destination. Denver, Tampa Bay and suburban Virginia were the betting favorites. Losing the Mariners was only a matter of when, not if.

In 1983, long before such tools as Twitter and Instagram, news of Argyros’ franchise scotching reached national media. Peter Gammons, writing in The Sporting News, raked Argyros in an article headlined “Blame The Owner for Mariners’ Woes.” The piece largely echoed the poundings Argyros absorbed from local media.

Argyros took such scathings in stride, never minding as long as his investment grew. Bottom line: he made a fortune turning off an entire region to major league baseball. While he hated losing games, frequently admitting it, he hated losing money more.

Argyros refused to spend much on players, usually disposing of promising youngsters before they cost him more than he wanted to pay. There seemed no end to a cycle of bad Mariner teams until 1987, the year Major League Baseball famously fined Argyros $10,000 for attempting to purchase the San Diego Padres while he still owned the Mariners.

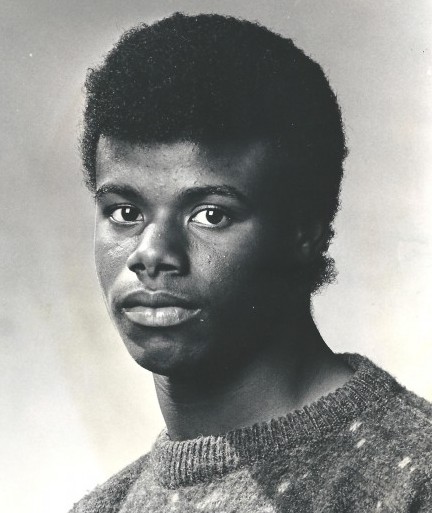

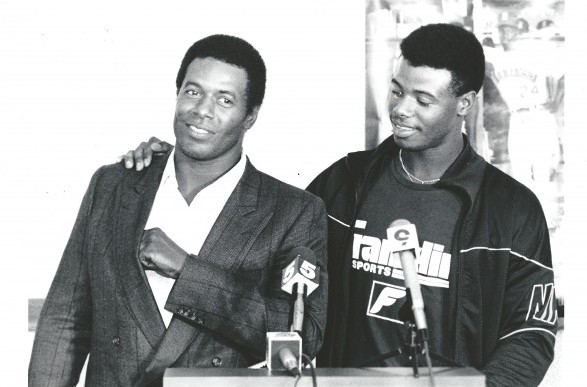

That spring, Ken Griffey Jr.’s name began to hit newspapers nationwide for the first time. A senior at Moeller High School in Cincinnati, “The Kid,” son of major league veteran Ken Griffey Sr., then with the Atlanta Braves, became one of a handful of favorites to go No. 1 in the June amateur draft. Seattle held the first overall pick.

Griffey Jr.’s competition included Willie Banks (6-foot-1, 185) of Jersey City, NJ., said to be a “Dwight Gooden-type” of pitcher. “He’s exciting,” declared Roger Jongewaard, the Mariners scouting director. “He’s got a great power fastball and a power curve. But he’s rough in a lot of areas, a little wild.”

Two other high school pitchers intrigued scouts, right hander Mike Mussini (6-1, 180) of Montoursville, PA. (not to be confused with Mike Mussina, a first-round pick in 1990), and right hander Dan Opperman (6-2, 185) of Las Vegas. Both had played for the U.S. junior team that defeated Cuba the previous year. Aside from Griffey, the top outfielder was Mark Merchant (6-2, 190) of Oviedo, FL.

The top college candidate to go No. 1, Cal State-Fullerton pitcher Mike Harkey (6-5, 220), had a reputation as a hard-toiling right hander rumored to being close to ready to pitch at the major league level, although Jongewaard harbored reservations.

“He’s got a great body, a great arm, and he throws hard,” Jongewaard said. “But he’s not as polished as some. He’s still a diamond in the rough.”

Argyros had no expertise in personnel matters, except to know when to shed a player who was coming due for a bigger paycheck, but he wanted Harkey largely on the grounds that he felt burned by the previous year’s No. 1, shortstop Patrick Lennon, a player whom the Mariners had taken out of high school and would cost, in Argyros’ view, too much to develop before he was major league ready.

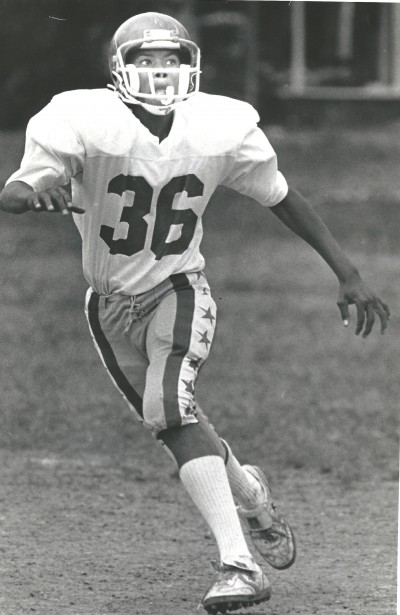

Argyros ultimately relented, allowing Jongewaard to make the decision, and two days before the draft Jongwaard told reporters he’d narrowed his choices to Griffey, Banks and Merchant, although that was a dodge. Jongewaard would take Griffey, a 17-year-old who, at 6-foot-3 and 200 pounds, and also a star football player at Moeller, was larger than his father and carried a .478 batting average with seven home runs in his final high school season.

“He’s got the potential to be another Dave Parker,” opined Jongwaard, who had signed Darryl Strawberry when he scouted for the Mets. “If he develops the way we think he can, he should hit between 25 and 30 home runs every year.”

The Mariners never had a superstar. Early in their expansion existence, they employed popular center Ruppert Jones, who inspired the few grandstand zealots who rattled around in the Kingdome to chant “Ruuuupe! Ruuuupe, Ruuuupe!” the way fans 35 years later would chant “Rauuuuuul.”

The Mariners had Alvin Davis and Mark Langston, both very good, neither great. Mainly they had non-descript veterans such as “Scrap Iron” Stinson, Steve “Bye-Bye” Balboni and Pat Putnam, who once played a game with a dead frog in his back pocket. They had employed a raft of characters such as prankster Bill Caudill, who enjoyed dressing up in Sherlock Holmes garb, and counted among their alums Mario Mendoza, he of the “Mendoza Line,” the arbitrary boundary of batting ineptitude.

The major marquee player before Griffey: Gaylord Perry, who notched win No. 300 in a Seattle uniform after winning 297 others elsewhere. Wary 0f Perry’s age, Argyros had him work on a month-to-month contract.

Through 12 seasons, six ending with 90 or more losses, the Mariners were a franchise almost entirely devoid of baseball highlights, easy to see why when this statistic is considered: Before Griffey, the Mariners played six seasons in which the staff leader in wins did not have a winning record.

But the Mariners were rife with lowlights, many comedic, such as the game — May 22, 1977 — when the Mariners not only had six base runners thrown out against Oakland, but were actually “thrown out for the cycle,” the Athletics tagging out Mariners at second, third and and even two at home. Another time — July 10, 1977 — Manager Darrell Johnson stormed to the mound and fined pitcher Roy Thomas on the spot for throwing four straight balls at Minnesota’s Mike Cubbage with the intent of hitting him — and missing all four times badly.

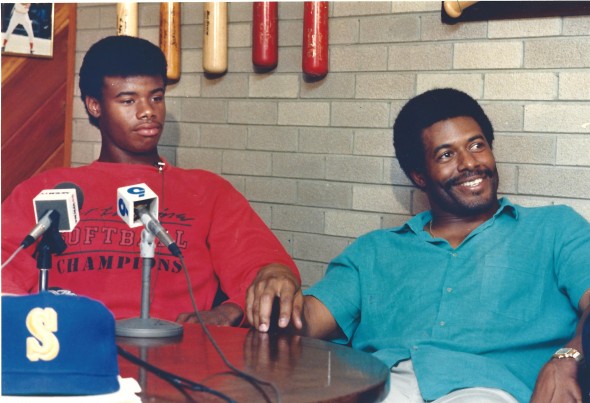

But on June 2, 1987, everything about the Mariners changed forever when they selected Griffey No. 1. His arrival not only extinguished talk of escape clauses and turned the conversation to baseball, it sparked the initial interest in local ownership of the Mariners, specifically from investors David Sabey and Bruce Engel. For 12 years, major league baseball had no future in Seattle. With Griffey stirring passions, it finally had one.

“He has the most ability of anyone we’ve seen,” Jongewaard said after selecting Griffey over Merchant. “He is ahead of many of his peers because he knows the game on and off the field.

“One reason is because he has been around his dad enough where he is familiar with it. The environment is not new, the life in baseball, the travel. He knows what to expect because he has been brought up in baseball.

“On the down side, that puts more pressure on him. He’ll always be compared to his dad, who is now the second-leading hitter in the National League.”

Jongewaard predicted that Griffey would rise through the Mariners minor league system faster than most prospects.

“He could,” Jongwaard said. “If he does well in A-ball, he could quickly move to Double-A and right up the ladder. Once he has success, then we can rush him, and I’m not using that as a negative term. Once a player gets his swing and his game, it doesn’t matter where he plays. But we’ll see. It takes a year and a half to get your footing, and then anything can happen. We’ve got some left-handed hitters, so we could end up trading him for a front-line pitcher.”

After the Mariners opted for Griffey, the Pittsburgh Pirates, with the second pick, took Merchant. The Minnesota’s Twins followed by taking Banks, and the Chicago Cubs went for Harkey.

Merchant never reached the majors. He played 12 minor league seasons, batting .263, rising as high as AAA. Banks pitched for seven major league organizations, compiling a 32-39 record in 181 games, mostly as a reliever. Harkey had a 131-game career with the Cubs, Athletics, Angels and Dodgers, going 36-36 in 131 appearances.

Signed by scout Tom Mooney, Griffey agreed to contract terms almost immediately, for a reported $175,000. His father and mother, Roberta, and a family attorney worked out the deal.

“It’s what you would pay for a first-round, first pick. We paid more for him than for anyone we’ve ever drafted,” said Jongewaard.

“He was a good kid and you could tell had grown up with baseball,’’ Mooney told boston.com. “It was very important to him to be the No. 1 pick, and there was no doubt. At the time, Mark Merchant was a ‘can’t miss’ type prospect, but there was no doubt that we were going to take Griffey with the first pick.

“The whole process was enjoyable. Got to know his dad. He was playing in Atlanta at the time, so it was mostly his mother and grandmothers who came to his games.

“The one thing about him which was different than other prospects is that he never felt the pressure that other kids do to perform with scouts in the stands. So many kids get nervous in that situation, and Junior was never nervous like that, and I’m sure it was because of his background.

“He was a kid who really cared about the game and he wanted to be great. And at the time, there was no better player in the country. That he went on to do what he did, probably not a surprise.”

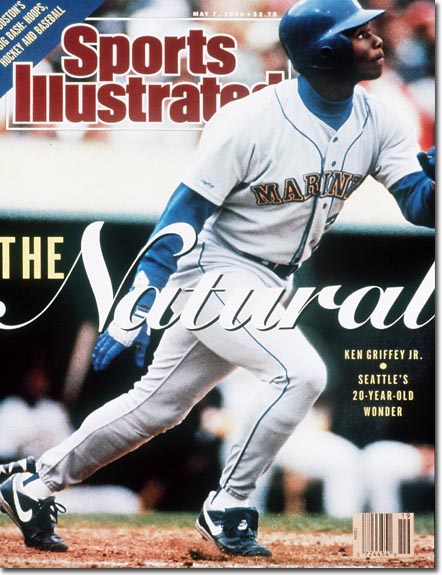

Griffey certainly exceeded Jongwaard’s expectations and, it turned out, Jongewaard didn’t know the half of it. Hours after the 18-year-old became a Mariner, Jongewaard reiterated the comparison he had made days earlier, saying, “I think he’s going to be a Dave Parker-type guy. All his tools are good, but his bat, that’s the major thing. He has the power to hit the ball a long ways. He could hit 25 to 30 home runs a year.”

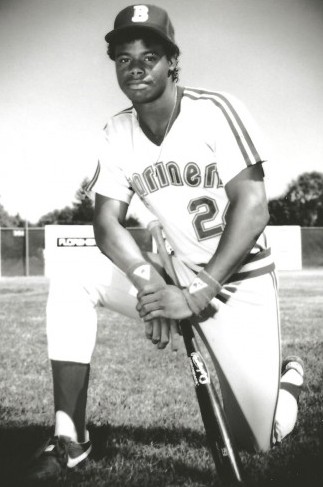

With nearly a dozen TV cameras capturing his every move, and Sports Illustrated and Sporting News reporters in attendance, Griffey worked out with the Mariners in the Kingdome three days after he signed.

“He stands up there a lot like his dad,” said Texas Rangers outfielder Tom Paciorek, a former Mariner (1978-81) who was among the substantial gathering to watch Griffey take his first professional hacks in early batting practice. “He’s got a sweet swing.”

Facing batting practice pitcher Phil Roof, a Mariners coach, Griffey, using his father’s bats, broke two of them in the first two minutes. He also popped a number of pitches into the seats in right, one into the second deck. Mostly, Griffey showed tremendous bat speed and an inclination to whack line drives.

“Wow!” said Mariner third-base coach Ozzie Virgil. “Let’s play him tonight.”

Bobby Tolan, a Seattle coach and one-time teammate of Griffey Sr.’s when the two played for Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine, had this take: “He looks like his old man as a kid. But he’s bigger. Ken Sr. was just a little thing.”

The Mariners assigned Griffey to Bellingham in the rookie Northwest League. It didn’t take him long to draw the first cheer of his pro career with the Baby M’s. The date: June 16, 1987.

A standing-room-only crowd of 2,516 in Belliingham treated Seattle’s new No. 1 pick to a rousing ovation as he trotted out of the home dugout and into his much-anticipated debut.

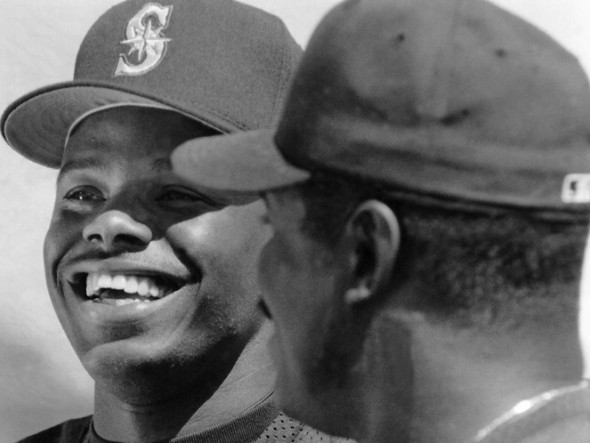

“I wasn’t expecting all of that,” Griffey told The Bellingham Herald. “I was expecting maybe a few people (would cheer), but not that many. That helps knowing you have the fans behind you.”

The warm welcome proved to be one of Griffey’s few highlights as Bellingham fell to the Everett Giants 5-4 in the Northwest League opener for both teams. Though he drew a walk in his first at-bat, Griffey failed to get the ball out of the infield after that, going 0 for 4 with a strikeout and three ground outs. Griffey had never gone 0-for-4 in his life.

“I’m a little bit disappointed,” Griffey admitted after facing a couple of tough left handers who had played college ball. “I was forcing my swing. I wish I would have gotten a hit, but those days will come. It’s just a matter of adjusting. I haven’t started to adjust yet.”

The adjustment period took him one day. On June 17, Griffey got his first professional hit, a three-run homer in the fourth inning off Gil Heredia in a 7-6 Bellingham loss to Everett in front of a sellout crowd of 3,122 at Everett Memorial Stadium in the Giants’ home opener.

For the rest of that abbreviated season, Griffey provided preview after preview of what Mariners fans would come to take for granted. He hit .313 with 14 home runs and, on July 4 in Everett, suffered a mild concussion when he slammed into the centerfield wall at Everett Memorial Stadium after catching a fly ball.

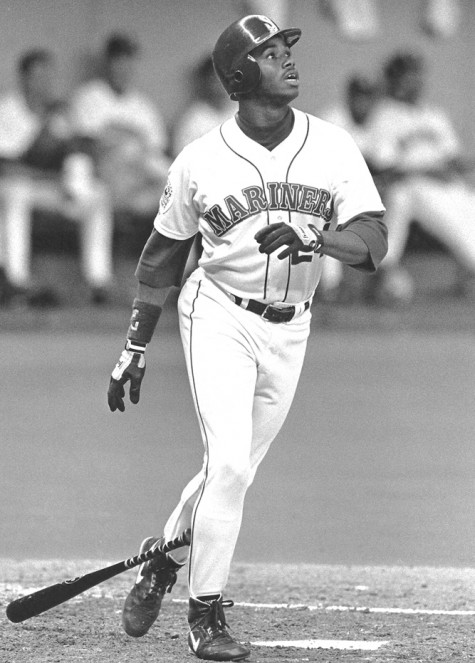

Griffey split 1988 between San Bernadino (A) and Vermont (AA), hitting .325 with 13 home runs, and showed up at the Mariners spring training camp in 1989, a longshot to make the major league roster.

“I’m not saying he’s Willie Mays yet,” said Don Reynolds (Harold’s brother), assigned to monitor Griffey, and who never had trouble mentioning Mays and Griffey in the same sentence. “But if he keeps it together, he can get there.”

It began in Griffey’s first major league spring training. He batted .397, put together a 14-game hitting streak, drove in 19 runs, and rookie manager Jim Lefebvre couldn’t deny him a roster spot.

“In the system scouts use, the highest mark you can give a prospect is an 80 — top marks in hitting, power, speed, fielding and instincts,” said Seattle’s senior scout, Bob Harrison. “Nobody ever gets an 80. In all the years I’ve scored kids, only a couple have come close. I gave Ken Griffey Jr. a 72.”

The Mariners opened the 1989 season May 3 at Oakland in a big week in Seattle sports. That night, Seton Hall and Michigan played for the NCAA basketball championship in the Kingdome. The next night, at the Coliseum, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar would play his final NBA game in Seattle.

Lefebvre penciled four rookies into his starting lineup to face Oakland ace Dave Stewart: Griffey in center, Omar Vizquel at short, Edgar Martinez at third and Greg Briley in right. Two of the four, Griffey and Vizquel, are future Hall of Famers, Martinez a maybe.

The center of attention, Griffey ripped the second big-league pitch he saw to the wall in center for a double. He hit two others to the warning track, the second after fouling off five two-strike pitches in a remarkable eighth-inning at-bat against lefty Rick Honeycutt, an original Mariner (1977-80).

“I threw him two sliders for strikes,” said Honeycutt, “and then a fastball that he somehow got the bat on. Then it was slider, slider, slider, and he kept hanging in. He made some very good adjustments on me. He seems to know what he’s doing.”

“That was a real professional at-bat,” said Lefebvre. “He gets two quick strikes and then fouls off some pretty tough pitches. He chokes up a half-inch on the bat with two strikes, does it instinctively, without us telling him. I’ve got guys who’ve played 10 or 12 years who won’t do that. We saw the debut of a great player tonight. That’s a great talent.

“The kid just has both God-given talent and a sense about him that comes, I guess, from being around the game. The great actors hang around the stage and learn what to do. Ken Griffey knows what to do.”

A unidentified reporter asked Griffey, “Where did you get that swing?”

“I was born with it,” Griffey replied.

Griffey made his regular-season Kingdome debut April 10 in a 6-5 Seattle victory over the White Sox. In his first home at-bat, Griffey drove a home run into the left-field seats off Eric King, irked that the teenager had taken him deep.

“I think he’s an easy out for me,” said King, “The only thing he hit off me was a mistake. I got the ball up and over the plate, and he just went with the pitch and hit it the other way.”

“Whatever floats his boat,” Griffey said, when told about King’s comment.

“I’ll tell you what,” said Lefebvre, wearing a “I’m A Lefebvre Believer” tee shirt. “I’ve never seen a rookie with as much promise. He’s like lightning in a bottle.”

When Argyros sold to Jeff Smulyan in 1989, he realized a $50 million profit on his $10.8 investment. Hard to quantify it, but Griffey gave Seattle fans an equally exorbitant return on the Mariners’ investment in him, all by doing what came naturally.

Since Safeco Field stands as testimony to Griffey’s deeds, and since you already have them memorized anyway, we’ll skip what happened next.

———————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Looking back, it’s amazing Junior only won 1 MVP award during his time as a Mariner. Not being on a consistent playoff contender most likely the reason. Could have made a case for Edgar in 1995 as well. Randy certainly should have been awarded two Cy Young’s. Frustrating that the franchise has yet to have made a WS appearance despite the rosters they’ve fielded.

Especially since he was named Player of the Decade for the 1990s by The Sporting News.