By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Born out of a lawsuit stemming from the loss of the Seattle Pilots, the Mariners had a long slog to respectability. In their first six seasons (1977-83), they lost 90 or more games four times, including 100-plus twice. Given the local novelty of major league baseball then, fans never expected much out of the early Mariners, a good thing because they didn’t get a whole lot more than misadventures.

One such occurred May 22, 1977. That night, the Mariners had six runners thrown out on the base paths against Oakland, including catcher Skip Jutze twice at home plate on the front end of double steals. For the night, the Mariners were infamously “thrown out for the cycle.” Remarkably, they won 6-2.

They weren’t as fortunate July 10 that year when starter Stan Thomas got roughed up for five runs in the first inning of a 15-0 loss to Minnesota. The most memorable sequence of his mound stint: Thomas tried to plunk Twins third baseman Mike Cubbage three times without hitting him once – in fact, missing him badly. Upset that Cubbage had stolen his girlfriend five years earlier while they were minor league teammates, Thomas was yanked and fined by manager Darrell Johnson.

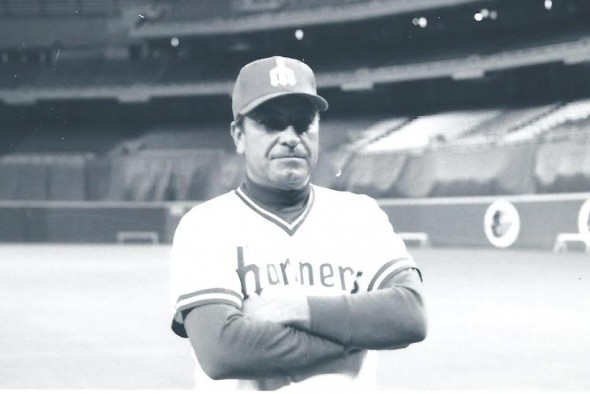

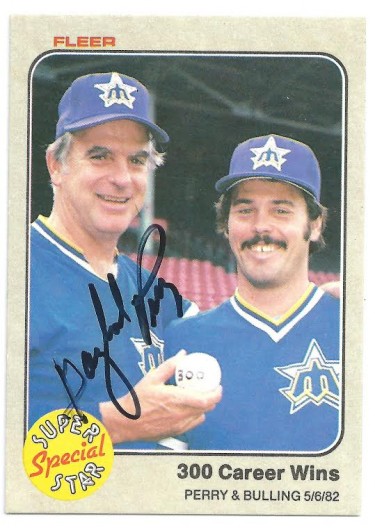

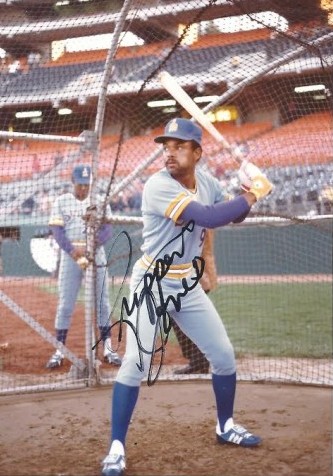

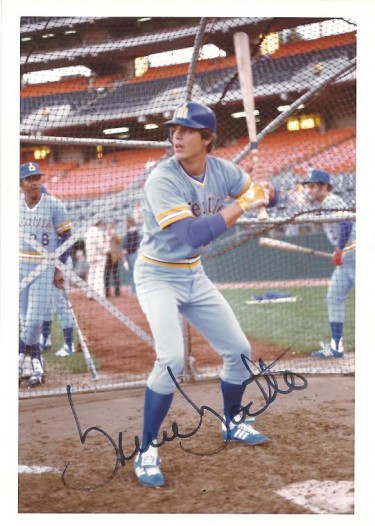

The Mariners featured a number of decent players in their expansion years, including CF Ruppert Jones, 1B Bruce Bochte, OF Tom Paciorek, LHP Floyd Bannister and, for a year or so, future Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry, who won his 300th game in a Seattle uniform. But they also employed a number of guys Casey Stengel could have been talking about when he famously asked, “Can’t anybody here play this game?”

The most memorable? Surely Frank MacCormack, a strapping 6-foot-4 righthander out of New Brunswick, NJ., who came to the Mariners as the 16th pick in the 1976 expansion draft. MacCormack pitched for Detroit and had the ability to throw a ball through a brick wall – if only he could have found the wall.

MacCormack began the 1977 season in the rotation, making his first start in the second game of a doubleheader against Kansas City April 24.

MacCormack walked leadoff hitter George Brett on four pitches and wild pitched him to second with his fifth. With two outs, he plunked John Mayberry. In the second inning, MacCormack walked Freddy Patek and Brett again leading off the third. After hitting Hal McCrae, MacCormack wild pitched Brett home.

After MacCormack walked Al Cowens leading off the fourth, Johnson yanked his starter who, although he hadn’t given up a hit, walked four, hit two and tossed two wild pitches among 15 batters.

“Mariners catcher Skip Jutze really got a workout,” reported The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “Frank threw two wild pitches with men on base, but when no one was on, he sailed the ball over the umpire’s head, or threw it wide and in the dirt, or close to hitters, who had to jump out of the way.”

Johnson gave MacCormack two more starts. After working seven innings over the three outings, MacCormack had no wins with 12 walks, three hit batters, four wild pitches and a balk. Even with that, Lou Gorman remained convinced MacCormack had potential.

“I’m going to send him down,” Gorman told The Seattle Times. “And I’ll keep sending him down until he gets it right.”

Gorman dispatched MacCormack to AAA Toledo of the International League, but the pitcher couldn’t find the plate. MacCormack then went to AA New Jersey with similar non-results. By June, two months after working in the Seattle rotation, MacCormack found himself on the mound for Class A Bellingham of the rookie Northwest League. In 27 innings with the “Baby M’s,” he walked an astonishing 51, plunked three and tossed 26 wild pitches.

“Look, I know I’m no Catfish Hunter,” said MacCormack, who couldn’t convince his mind that 60 feet, 6 inches was not too far away to hit a target 17 inches wide. “It’s like there was a giant wall in front of me. On my side, I’m alone and it’s dark. On the other side, the sun is shining and there’s a whole lot of people having a picnic.”

MacCormack never pitched in the majors following his three starts in 1977 and found himself out of baseball by early 1979, when the Mariners threw in the towel that had MacCormack’s name on it.

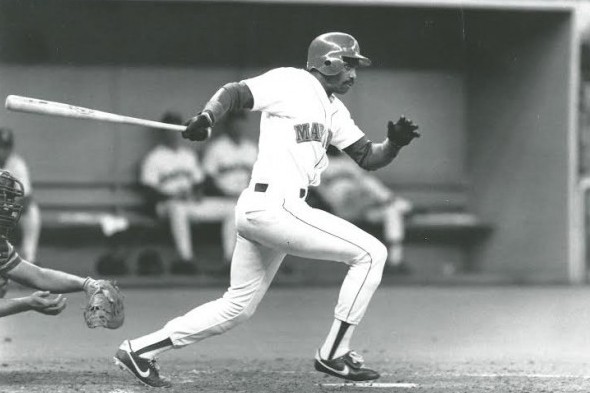

Just as many fans were ready to give up on the Mariners as their bad luck stretched into a seventh year, along came Alvin Davis to take some of the slapstick out of the Kingdome.

The Mariners had not expected Davis to be with them in 1984, or at least as early as he arrived. Until April 11, the 23-year-old had played in only 84 AA (Lynn, MA.), 131 AA (Chattanooga) and one (Salt Lake City) Pacific Coast League games.

“My goal this season,” Davis told The Post-Intelligencer during spring training,” is to reach the major leagues by September. I’ll be satisfied with that.”

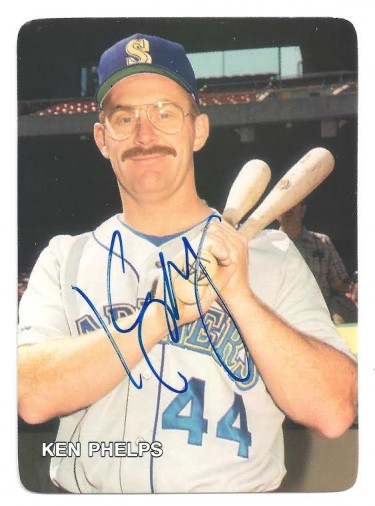

But when regular first baseman Ken Phelps suffered a broken finger (hit on the right hand by a pitch thrown by Milwaukee’s Jerry Augustine), the Mariners summoned Davis from the Salt Lake Gulls and started him at first base against the Boston Red Sox. Batting sixth, Davis couldn’t get around on a Dennis Eckersley fastball and flew out to left.

But in the fourth inning of a scoreless tie, Davis turned on the fifth major league pitch he saw and rammed it off the second-deck façade in right, driving in Barry Bonnell and Al Cowens for a 3-0 lead.

The ball traveled an estimated 450 feet and was the prominent blow in a 6-1 victory. Davis followed with a pair of walks, one intentional, and Phelps’ career as Seattle’s first baseman was essentially over (the Mariners moved Phelps to DH and traded him in 1988 to the New York Yankees, a hugely one-sided swap in Seattle’s favor that netted Jay Buhner).

In his first 10 at-bats, Davis delivered eight extra-base hits, including a trio of run-scoring doubles. He hit successfully in his first nine games, establishing a franchise record for most consecutive games collecting a hit to start a career.

Davis performed so well over the first half — .287 average, 18 home runs, 51 walks, 65 RBIs – that he became the first position player groomed by the Mariners to make the American League All-Star team, earning a reserve spot by receiving an AL-high 118,872 write-in votes. Only two other rookies made 1984 All-Star teams, Dwight Gooden of the Mets and Juan Samuel of the Phillies.

Davis enjoyed immediate success in the majors because he could handle hard stuff on the inside part of the plate. And when pitchers began feeding him breaking balls, he successfully adapted after a short slump.

“One of the best things about Alvin is that he has exceptional vision,” said Mariners hitting coach Ben Hines. “He has a pretty good idea of where the pitcher releases the ball.”

Born Sept. 9, 1960 in Riverside, CA., Davis attended John W. North High School, graduating in 1978. The San Francisco Giants selected him in the amateur draft while he was still a high schooler, and the Oakland Athletics picked him when he later starred at Arizona State.

“When he told the Athletics he wanted to remain in school and complete his education, some scouts thought he didn’t have the intensity to play in the major leagues,” said Hal Keller, Seattle’s VP of baseball operations. “But I saw him in high school and he was already an outstanding hitter. He just didn’t have a position yet. He had tried to play third base and he couldn’t do that. But we knew he could hit.”

Davis slipped through five rounds of the 1982 June draft before Keller, at the urging of scout Bob Harrison, plucked him in the sixth. After his first half-season, he drew raves from all over baseball.

“One of the things he could always do was hit,” Harrison told The Seattle Times. “I knew his bat could carry him to the big leagues.”

“He’s as good-looking a hitter as has come into the league in years,” said Toronto manager Bobby Cox.

“I watched him for five days in Venezuela and he put on some kind of show. He has so much poise,” added California Angels manager Gene Mauch.

Davis hit .284 with 27 home runs, established club records for RBIs (116), game-winning hits (11), game-winning RBIs (13), and grand slams (2). At the time, his 116 RBIs were the most by an American League rookie since Al Rosen collected the same amount for Cleveland in 1950. Davis also set a major league rookie record by drawing 16 intentional walks.

As a result, Davis turned the AL Rookie of the Year award voting into a rout. He received 25 of 28 first-place votes for 134 points, overwhelming teammate Mark Langston, who had three first-place votes and 82 points. They were the only players named on all 28 ballots. Kirby Puckett finished third with 23 points.

Davis was also the only unanimous choice on the Topps Major League Rookie All-Star Team, leading all vote-getters. Dwight Gooden of the Mets fell one vote shy.

In all the years since Davis’ debut season, only three Mariners first basemen – Tino Martinez (.910) in 1995, Richie Sexson (.910) in 2005 and John Olerud (.893) in 2002 posted a better individual season than Davis’ 1984, when he recorded an OPS of .888.

Between the time of Davis’ arrival in 1984 and Ken Griffey Jr.’s debut in 1989, the Mariners didn’t have much to celebrate. They never finished higher than fourth in the seven-team AL West and usually wound up from 26 to 28 games out of first place. But Davis carved a commendable career. Among the highlights:

- Named the Mariners’ Most Valuable Player by the Seattle chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America in 1984, 1988 and 1989.

- Finished his career with 1,163 hits, 160 home runs, 667 RBIs and a .280 batting average.

- Hit nine career grand slams, last on Sept. 28, 1990, against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park.

- Hit two home runs in a game three times, May 9, 1986 against the Toronto Blue Jays in the Kingdome; July 9, 1987, against the Boston Red Sox in the Kingdome; and July 29, 1987, against the Minnesota Twins in the Kingdome.

- Had five career walk-off hits, including ninth-inning, walk-off home runs against the Minnesota Twins on consecutive nights – Aug. 15-16, 1986.

- Had a career-high five hits (5-for-5) in a 5-2 win over the Cleveland Indians June 17, 1986 at Municipal Stadium.

- Homered in four consecutive games, April 22-25, 1986, including the game winner April 24 at Oakland.

- Collected his 1,000th major league hit July 22, 1990 (off Teddy Higuera), becoming the first Mariner to reach that milestone.

- Had a career-high 14-game hitting streak from May 1-14, 1986, batting .468 over that span (22-for-47).

- Had a career-high three doubles April 18, 1984, in a 5-4 win over the Oakland Athletics at the Kingdome.

- Produced a franchise-record eight RBIs in a 13-3 victory over the Toronto Blue Jays at the Kingdome May 9, 1986 (went 3-for-4 with a grand slam, three-run homer and RBI single).

Davis still ranks among the franchise’s top 10 in numerous offensive categories. He played his final game for Seattle Oct. 6, 1991. / David Eskenazi Collection

- In 1987, became the first Mariner to record two seasons of 100 RBIs (had 100, to go with 116 in 1984).

- Scored three runs in a game 13 times, last time Aug. 31, 1990.

- Tied a major league record for a first baseman by making 22 putouts May 28, 1988 against the Yankees.

By the time Davis played his final game for the Mariners – Oct. 6, 1991 – he was the club’s all-time leader in at-bats, hits, doubles, home runs, RBIs, total bases, extra-base hits and walks.

Griffey and Edgar Martinez ultimately broke all of Davis’ marks, but Davis still ranks among the franchise’s top 10 in games (1,166), hits (1,163), home runs (160), extra-base hits (382), at-bats (4,136), doubles (212), RBIs (667), walks (672), runs (563) and total bases (1,875).

The Mariners elected to let Davis walk after the 1991 season when he slumped to .221/.299/.335 with 12 home runs, reasoning that it had Pete O’Brien signed for another two years and Tino Martinez in the wings.

Davis did not receive another major league offer until February 1992, when he accepted a one-year deal with the California Angels. Davis lasted 40 games with them, hitting .250 without a home run. His final highlight occurred June 25 when he returned to the Kingdome for the first time and played what turned out to be his final major league game.

For the occasion, the Mariners held a special “Alvin Davis Night” in front of 14,219. Mariners catcher Dave Valle and second baseman Harold Reynolds, two of his best friends, took part in the pre-game ceremony, which turned tearful at times as Davis talked about his career in Seattle.

“When you’re a kid, you dream of playing with the best and against the best in the big stadiums,” Davis said, addressing the crowd. “But you never dream you’d have a day like this. It’s good to be home. This is my home. Everything good that ever happened to me was right here in front of all of you.”

The Mariners presented Davis a framed poster of himself and a crystal trophy block with the inscription, “Thanks for all the great years, you will always be Mr. Mariner.”

“I had to suck it up to keep going,” said an emotional Davis. “It’s definitely an honor for them (the Mariners) to do this, but it is kind of embarrassing. I really appreciate the gesture because it’s more of an honor than just saying I was a good guy. They’re going to have better players than me as far as what a guy brings to the field. But this is embarrassing because this isn’t the way I’d like to go back.”

After the ceremony, Davis broke out of a 1-for-28 slide with two hits and a walk, including a run-scoring single in his final at-bat, off Russ Swann. Despite that effort, the Angels released Davis the next day, ending his major league career.

Five years later, on June 14, 1997, Davis was feted in another Kingdome salute when the Mariners made him the first member of the team’s new Hall of Fame. After the pre-game ceremony, Davis threw out the ceremonial first pitch, caught by Griffey.

“Do you think there will ever be another Mr. Mariner?” Griffey later asked reporters in the clubhouse. Then Griffey answered his own question. “I don’t,” he said. “Alvin is the original and only one.”

——————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Great read. I’d forgotten about those six baserunners getting thrown out in the same game, but I hadn’t forgotten Frank McCormack’s quixotic journeys in search of the strike zone. As exasperating as the early days were, it was more fun to go to Mariners games back then because you never knew what was going to happen except that it wasn’t likely going to be a pitcher’s duel.

AD was the first legit homegrown M’s star (along with Langston) and he was always a true credit to the franchise on and off the field. Junior was right: Alvin Davis was the original and only Mr. Mariner.

AD was a true blessing to the franchise without doubt. He’s earned the title of Mr. Mariner. Though I understood why Pete O’brien was signed by the M’s, (a better defensive player and new owner Jeff Smulyan wanted to make a big free agent signing) but I’ve always wondered if AD was left at 1B would his career have gone longer? IMO, he wasn’t comfortable being the full time DH.

Though the M’s don’t have the winning tradition of the Yankees and Red Sox they do have a history uniquely their own. From the humorous moments like the Coneheads, Langston moonwalking on top the dugout during a rain delay and Lenny Randle blowing a ball foul to Gaylord’s 300th win, Junior and Ichiro’s MVP years and Felix’s perfect game it’s a history that all Mariner fans can identify with. I’ve noticed over the years that many players seem to know that history quite well, especially the retired players. Junior always surprises me at just how much detail he’s familar with in regards to Mariner history.