By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Although “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” was written in 1908 (by New Yorkers Jack Norworth and Albert Von Tilzer), it took decades to evolve into baseball’s biggest hit. The song’s first rendition at a major league game occurred in 1934 in St. Louis, where a jug band led by Cardinals third baseman Pepper Martin played it before the start of the World Series. It didn’t become a seventh-inning stretch tradition until the 1970s when broadcaster Harry Caray made it so at Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

Caray often sang “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” with fans seated near his broadcasting perch. Then one day, White Sox owner Bill Veeck, always on the prowl for a gimmick, outfitted Caray’s booth with a microphone so fans throughout the ballpark could join the choir.

Caray eventually moved to Wrigley Field and brought his seventh-inning singing with him. It evolved into a ritual that now occurs in almost every ballpark. Today, “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” is generally acknowledged to be the third most-performed song in America behind “The Star Spangled Banner” and “Happy Birthday.”

Although Caray did more than anyone to popularize the singing of the song during the seventh-inning stretch, the practice actually began three decades before Caray through the efforts of a man named “Rattlesnake” Bill Mulligan, whose life probably couldn’t be replicated today.

Born Oct. 1, 1890 in Seattle, Mulligan grew up in Spokane and developed into a star athlete, after which he toiled as a mule-skinner, automobile salesman, service station operator, football and basketball official, athletic director, boxing promoter, farmer and brewery manager.

How that portfolio prepared Mulligan to guard Emil Sick’s nickels isn’t clear, but Sick brought Mulligan aboard as his business manager in 1938, shortly after Sick purchased the Pacific Coast League’s Seattle Indians, a franchise in a universe of financial hurt, from Bill Klepper.

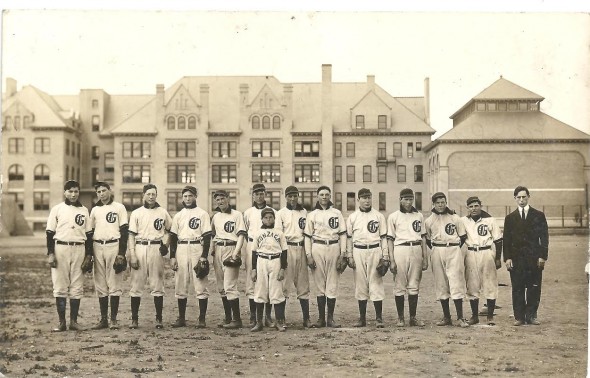

Mulligan worked his way through Gonzaga University as a mule-skinner on his father’s road construction crews, graduating in 1910. For three years, he captained the school’s football, basketball and baseball teams, playing under head coach George Varnell, later a prominent West Coast football and basketball referee and, even later, associate sports editor of The Seattle Times.

After graduation, Mulligan had an offer to play shortstop for Spokane’s minor league baseball club, but turned it down because of the objections of his parents, who believed that life as a ball player offered no future (Mulligan eventually logged time in the old Northwest League in the late 1920s).

For a while, Mulligan operated a string of Spokane filling stations, which provided him an opportunity to show off the kind of creativity that would mark his career as a baseball executive. Mulligan became the first service station owner in the state to install automatic grease hoists.

In the late 1920s, Mulligan returned to Gonzaga to serve as the school’s graduate manager (athletic director). He hired future Pro Football Hall of Famer Ray Flaherty, who subsequently coached NFL title teams in Washington in 1937 and 1942, as the school’s basketball coach (1929-30), and introduced night football to the Northwest by installing floodlights at the Gonzaga athletic field.

After working for several years in the Pacific Coast Conference as a football and basketball official, Mulligan entered Sick’s employ in 1936 as the manager of Sick’s brewery in Portland. Two years later, Sick purchased the Indians from Klepper and brought Mulligan to Seattle to negotiate player contracts and oversee operations at newly constructed Sicks’ Stadium.

“I didn’t know what to do with the club when I bought it,” Sick told The Sporting News in 1942. “But the situation when I took over was so deplorable that it reflected badly on the city. Someone had to be sufficiently civic minded to do something about it.”

Sick did plenty. He formed a half-million-dollar corporation and started immediate construction on a baseball plant valued at $350,000. Sick surrounded himself with capable executives and told them to run the club. The first order of business: Find a field manager. Sick gave that task to Mulligan.

Morton Moss, a columnist for The Los Angeles Examiner, explained what Mulligan did next:

“Mulligan adjusted his pith helmet and sallied forth on a safari across the Republic in search of the desired managerial specimen. During his travels, Mulligan encountered Joe McCarthy, manager of the New York Yankees. Mulligan asked McCarthy to make a recommendation on the top man to run the Seattle franchise.

“‘If you’re asking me for the top man,’ McCarthy replied, it’s Jack Lelivelt. If you get him you won’t be sorry.’”

Mulligan relayed this intelligence to Sick, who ordered Mulligan to hire Lelivelt away from the Chicago Cubs, for whom he had been working as a scout. McCarthy was correct: Mulligan and Sick made the perfect hire in Lelivelt (see Jack Lelivelt’s Seattle Rainiers).

“From the day the doors opened at Sicks’ Stadium, baseball has been Seattle’s favorite sport,” Times reporter Alex Shults wrote in 1942. “In just a little more than three seasons there the turnstiles have whirled more than a million and a half times. Season box reservations are sold out before the season opens and there’s always a waiting list.

“Whereas women used to be only occasional customers, now some 30 percent of the crowd comes from the fair sex. Mulligan has the rest of the baseball world copying the innovations he has installed in Sicks’ Stadium for the pleasure of those million and a half turnstile twirlers.”

Shults made this contrast:

“When Sick bought the club, it wallowed around in the lower regions of the standings, without a home of its own (the Indians played at Civic Stadium on the present site of the Seattle Center) and with the sheriff as the No. 1 fan, as he was always about, slapping attachments on the box office. And then Sick purchased the club. Or, rather, he paid off the bills and swapped stock with the former stockholders, giving them shares in a new corporation and a bonus besides. The club became attuned to public imagination immediately.”

After changing the club’s nickname from Indians to Rainiers, signing pitching sensation Fred Hutchinson out of Franklin High School, and adding Edo Vanni from Queen Anne High, the Rainiers stormed through the 1938 Pacific Coast League season under Lelivelt’s command, nearly winning the pennant.

Even without Hutchinson, sold to the Detroit Tigers in the winter of 1938, the Rainiers won three consecutive Pacific Coast League championships between 1939-41, including two under Lelivelt and one under Bill Skiff, who succeeded Lelivelt after he died from a sudden heart attack.

But it was Mulligan who elevated ballpark visits into something special, making the Rainiers Seattle’s most popular team throughout the 1940s.

“There is a friendly, homey spirit in the Seattle ballpark, which is in strict contrast to the cold, purely businesslike atmosphere of other cities,” wrote Elliott Metcalf, a columnist for the Tacoma Times. “This was Mulligan’s idea, and it does add greatly to the enjoyment of the fans, making them feel at home. Everyone sings ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ at the beginning of the game and ‘Take Me Out To The Ball Game’ during the seventh-inning stretch. Seattle is the first town to inaugurate this.”

Seattle is also the birthplace of The Wave (1981), but that’s another story.

Think of the extraordinary efforts – giveaways, theme nights, fireworks shows — to which the Mariners go to make their games a memorable experience. Mulligan preceded the Mariners’ promotional acumen by four decades.

Rattlesnake Bill – he received the moniker by clubbing to death a rattler while playing golf with Spokane native Bing Crosby at Del Mar — planted shrubs and flowers along the outside walls of Sicks’ Stadium to enhance the ambiance. He placed cut flowers throughout the inside the park. During the Christmas season, the entire front of the stadium was decorated with lighted trees, wreaths and colored flood lights, and the public address system entertained each evening with holiday carols.

Every year, the Mariners salute armed forces personnel. This is what Mulligan did: During World War II, he introduced a series of “Shut-In” nights at Sicks’ Stadium. Shut-ins from throughout the Northwest arrived at the park in ambulances, wheel chairs, on crutches, some even on cots. The Rainiers paid for their transportation and provided free tickets. They sat in seats relinquished by regular season-ticket holders.

Mulligan received his highest career honor in 1944 when The Sporting News named him its Minor League Executive of the Year.

Mulligan’s citation read: “Given almost carte blanche by Sick, Mulligan has assisted in assembling the playing talent, supervised the promotional and business end of the club, efficiently handled the large crowds that flock to Sicks’ Stadium, and led in suggestions for the betterment of the game. Mulligan is thoroughly schooled in sport, conversant with both the performances’ and fans’ point of view and, as a result, has been an outstanding success as an executive.”

Mulligan worked for Sick until Oct. 11, 1946, when he resigned to become general manager of the Portland Beavers. Times columnist Emmett Watson, who regularly covered the Rainiers, had this to say:

“Like the guy who can’t see the forest for the trees, Seattle has sort of overlooked Irish Bill, the man who made Sicks’ Stadium the best-run ballpark in the minors. His successor will have to continue a lot of innovations of Mulligan’s whether he likes it or not. For nine years, Sicks’ Stadium has been Irish Bill’s baby. You could kick a dent in the fender of his car before you’d deface any part of the Rainier Valley park.

“Gonzaga Bill could cut ice with a sharp glance if he thought the price was wrong. In the matter of player contracts, sale of players, purchase of players and overhead costs, he’s a tough monkey. But when the Irishman relaxes to become one of the boys there’s nobody quicker on the draw when the check comes. Mulligan’s 39-year business and athletic career could fill a whole sports page.”

Watson told this story:

“There was a time when Bill thought he saw a dog scurrying around in the left-field bleachers after a night game. Closer inspection revealed a drunk crawling about on his hands and knees searching for something.

‘What’s going on?’” demanded Mulligan.

‘Lost my false teeth,’ the drunk replied.

“Irish Bill spent a half an hour helping the guy find his choppers.”

Mulligan served as Portland’s general manager for seven years, but health problems marked his final two. He suffered a strangulated hernia in a car crash when he skidded on an icy highway, suffering a broken kneecap and cracked hand. Then the biggie: A heart attack Feb. 8, 1953 that claimed him at age 63 only a week after he had been pronounced nearly recovered from abdominal surgery.

Although a keen businessman who insisted on getting value received for his expenditures, hundreds vouched for his generosity. When Mulligan sold Leo Thomas to the St. Louis Browns at the close of the 1951 season for $15,000, Mulligan sent the infielder a check for $1,500 because “he always gave me his best; now I’ll give him my best.”

Another time, while Mulligan ran the Portland club, he had an argument with a pitcher named Red Adams over Adams’ salary. Mulligan prevailed and Adams signed at Mulligan’s figure. Adams followed with a run of bad luck, losing a series of low-scoring games, mostly shutouts by 1-0 and 2-0 scores in which Adams gave up no more than two hits, yet lost, including one game in which he had 13 strikeouts.

“After the 13-strikeout game, Mulligan called in Adams, tore up the old contract and wrote a new one retroactive to the opening of the season at Adams’ figure,” reported Oregonian sports editor L.H. Gregory, who quoted Mulligan as telling Adams, “You’ve shown that you were right. We’ll pay you the salary you wanted.”

By the time Mulligan died, “Take Me Out To The Ball Game” had become a standard, seventh-inning feature at nearly every Pacific Coast League park.

“It’s his legacy to baseball,” wrote Watson.

—————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

4 Comments

Great Story, David & Steve. Seattle has such a colorful history, and stories like this help keep that history alive.

On behalf of David, thanks for responding. We appreciate it!

Wonderful story, but golfers will want to know … what club did he use on the rattler?

I’d have used a wedge. You have to really get under snakes to get any carry out of them and a number 9 will give you that lift, although you might want to choose a 7 if you need a little more distance. As always, it depends on the hole.