By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

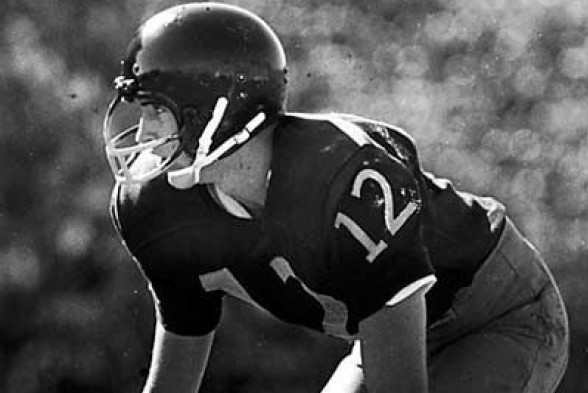

After the University of Washington freshman football team wrapped up its 1964 season, coach Ed Peasley met with head coach Jim Owens to brief his boss about which of the Pups Owens could count on to contribute to the 1965 varsity. When the conversation turned to Al Worley, a position-less product of Wenatchee High School, Peasley was adamant that Worley wouldn’t be of any use.

“Al Worley will never play varsity football at the University of Washington,” Peasley confidently told Owens.

Had Worley been privy then to Peasley’s negative assessment, he might not have disagreed.

“I was surprised that Washington even offered me a scholarship,” Worley said. “I was not what you’d call a widely recruited athlete. I was an all-nothing in high school.”

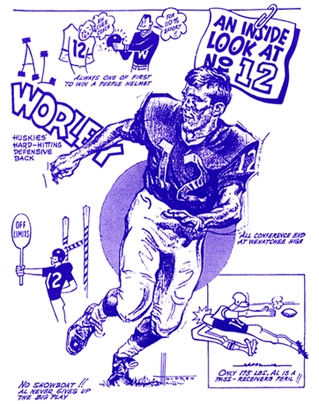

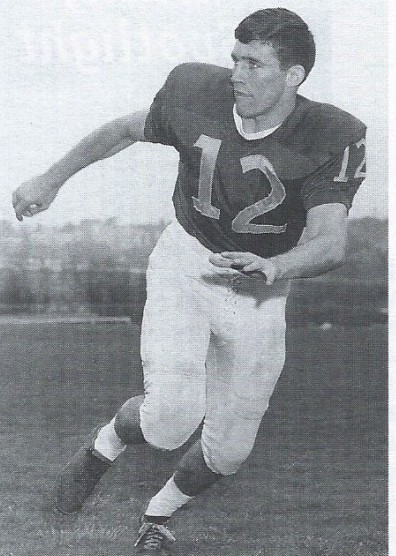

Well, not quite. A three-sport standout at Wenatchee High, Elvin “Al” Worley made the Western Conference All-Star football team as a senior end in 1963. He also completed his prep basketball career as the school’s fourth all-time leading scorer and played some decent baseball for the Panthers. But Worley’s freshman season at Washington included only two plays in one game at split end.

“I did exactly nothing,” added Worley, who once provided Seattle Times columnist Georg N. Meyers with this self-scouting report: “I was slow, small, bowlegged and bullheaded.”

When Worley turned out for his sophomore year, he hoped to get a chance to play defense. But a broken hand derailed that plan and Worley was forced to redshirt the 1965 season. Although it appeared that Peasley’s prediction would come true, Worley declined to accept his nomination as a reject.

He saw increased playing time in the Washington secondary in the 1966 and 1967 seasons, when the Huskies combined to go 11-9, and worked himself into a full-time starter by the time UW opened the 1968 season.

Even in a age of bloated statistics, it is staggering what happened next, and even more staggering that what Worley accomplished is still an NCAA and Washington record.

The 1968 Huskies didn’t throw much of a scare into anybody. In a 3-5-2 season, including 1-5-1 in conference play, they were blanked twice, including 24-0 by Washington State in the Apple Cup, and scored a touchdown or less in five games. Washington scored 30 or more points only twice, including 35 in the season opener against Rice in the first Husky Stadium game played on AstroTurf.

That was the day – Sept. 21 – that Al Worley formally introduced himself.

Washington needed Ron Volbrecht’s 51-yard field goal on the final play to force a 35-35 tie and achieve the “thrill of avoiding defeat,” as The Seattle Post Intelligencer caustically described it. The last-second tie largely obscured Worley’s contribution – two interceptions. They served as warmup.

In Washington’s 21-17 victory Sept. 28 at Madison, the Huskies needed four interceptions in the fourth quarter to hold off a Wisconsin team that it had once led 21-0. Worley recorded three of the picks, including one with Wisconsin threatening on the UW six-yard line, the other with the Badgers on the Washington two.

“I think they were picking on me,” Worley quipped after his three interceptions established a conference record.

“Al always had a nose for the football,” explained Joe Schooler, a Wenatchee native who played ball with Worley at Wenatchee High. “He just had a gift for it.”

Worley collected one interception Oct. 5 in a 35-21 loss to Oregon State, had no picks in a 3-0 home loss to Oregon and one in a 14-7 loss to USC in Los Angeles in a game in which O.J. Simpson trampled the Huskies for 172 yards and scored both Trojans touchdowns.

Worley’s pick off USC quarterback Steve Sogge was his seventh in five games, barely giving Worley bragging rights in his own family. His younger brother, Larry, a quarterback/defensive back at Wenatchee High, had nine interceptions in the Panthers’ first six games.

Al and Larry grew up sons of a janitor of scant means. As Al told Meyers, “We had a lot of thin days at home. We were a family (10 children) that had to scrape and scrap for everything to hold together. I couldn’t believe my luck, to be able to get an education and play football at a school like Washington.”

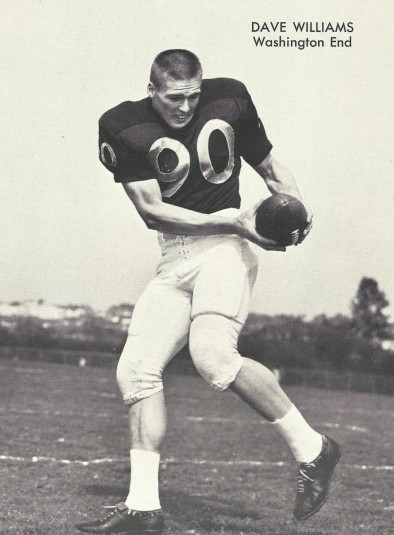

While Peasley could not envision a varsity career for the undersized Worley, Dave Williams, the UW’s All-America tight end and a future No. 1 NFL draft pick, did not share that sentiment.

“That kid in the red shirt,” Williams said, describing Worley in Washington practices, “gives me more trouble than anybody else.”

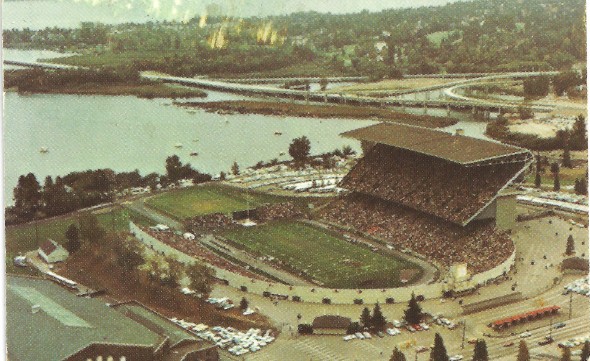

Worley achieved national recognition Oct. 26 when he had four of Washington’s school-record eight interceptions in a 37-7 victory over Idaho at Husky Stadium. The four picks also re-established the conference single-game record and hiked Worley’s season total to 11, one shy of the Washington record of 12 by Bill Albrecht in 1951.

Impressive as was his interception total, his individual work against Idaho’s Jerry Hendren was equally so. A Spokane native, Hendren entered the game as the national receiving leader with 63 catches for 965 yards and eight touchdowns. Worley held him to two catches for 27 yards.

A week later (Nov. 2), in a 7-7 tie with California, Worley produced two more interceptions, including one he returned 32 yards for a touchdown. The first matched Albrecht’s 1951 school record, the second – and Worley’s 13th — tied Oregon’s George Shaw (also 1951) for the most in a season in NCAA history.

Worley claimed the NCAA record as his own in a 6-0 win over UCLA Nov. 16 at Husky Stadium. Near the end of the first half, the Bruins reached the Washington 45-yard line. With 24 seconds remaining, Bruins quarterback Jim Naber orbited the ball toward his halfback, Gwen Cooper.

“I thought that thing was never going to come down,” said Worley.

It did, smacking Worley in the breadhooks at the three-yard line. Worley returned it 35 yards, preventing what could have become the winning touchdown.

Worley set the record of 14 – he had 11 more interceptions than his team had wins — in 10 games and no one has seriously challenged it since.

When North Carolina State’s David Amerson collected 13 interceptions in 2011, he became the first player in two decades to threaten Worley’s single-season record. In fact, Amerson was the first FBS player to pick off more than 12 since Worley’s career year, and he required 13 games – not 10 – to do it.

Even factoring bowl games in season statistics, it’s safe to say no one will break Worley’s NCAA-recognized 1.4 interceptions per game.

There’s another reason why Worley’s single-season record of 14 is so boggling: Since 1950, no Husky aside from Worley has had more than 13 interceptions in a career, including Albrecht, who had 12 in 1951 and one the remainder of his career.

After Worley’s 14 and Albrecht’s 12, the most interceptions by a UW player in a season is eight by Larry Hatch in 1946, a total matched Walter Bailey in 1991. In the past 15 years, no player has had more than six (Derrick Johnson, 2003). Marcus Peters led the 2014 Huskies with three before Chris Petersen booted him from the program, and no other UW player had more than two.

Forty-seven years after his 14 picks (that’s eight presidential administrations), Worley still holds all-time Husky records for most interceptions in a game, season and career. He became a consensus All-America (Washington did not have another until Chuck Nelson in 1982) along with the likes of Simpson, QB Terry Hanratty of Notre Dame, RB LeRoy Keyes of Purdue and Miami LB Ted Hendricks.

Worley ended his college career by intercepting a pass in the Hula Bowl (he also represented Washington in the East-West Shrine game) and was inducted into the Husky Hall of Fame in 1992. He now has a chance at a bigger accolade: Induction into the College Football Foundation Hall of Fame. Worley was among a dozen former players from the Pac-12 conference nominated last week and the only one from Washington.

At 5-foot-10, 175 pounds and hardly a speedster, Worley had scant chance at an NFL career. Neither did he draw interest from the American Football League or Canadian Football League. Not quite ready to quit, Worley, in May 1969, signed with the Seattle Rangers of the Continental Football League, a semi-professional club that played its games at Memorial Stadium on the Seattle Center grounds in front of crowds that ranged from 4,000 to 6,000.

Although they had a loose working arrangement with the Denver Broncos, who used the Rangers to help develop players, the Rangers never were sufficiently funded (although they once employed the legendary Ernie Nevers as a kicking coach) and folded due to financial problems after Worley’s first season, when he was a Continental League All-Star.

Had the NFL – or AFL – beckoned after his Continental All-Star season, Worley would have been tempted.

“If there was something there, I probably would have taken it,” said Worley. “But there wasn’t.”

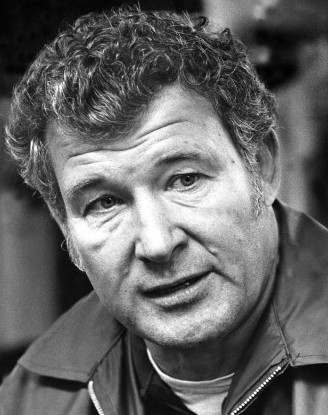

Worley became a part-time Washington assistant and a substitute teacher in Seattle before moving full time into college coaching. His first job: at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, where the head coach was Ed Peasley – the same Ed Peasley who lettered at Washington as a receiver from 1957-59, and the same Ed Peasley who told Owens in 1964 that there was no way Worley would ever play varsity football for the Huskies.

Worley spent four years in Flagstaff and then moved to Portland State to work under Mouse Davis, who developed the run-and-shoot offense with quarterbacks June Jones and Neil Lomax. In 1979, Worley accepted a position as head coach of the Yokosuka Base Seahawks, a U.S. Navy Service team in Japan.

Worley eventually settled in Hawaii and is nearing retirement after a long career as a facilities and projects manager for an Oahu recreation company close to Pearl Harbor.

“It (Hawaii) just grew on me and it became home,” said Worley.

He doesn’t think much anymore about the record he set so many years ago, only when somebody brings up the subject, which isn’t often. Pressed, he can recall all of the interceptions, especially one against California he returned 32 yards for a touchdown.

“They were a good team and we went up and down the field a couple of times,” Worley said. “I can remember an interception and a touchdown, and I threw the ball in the air about 20 feet after it and got chewed out.”

That was pretty much the extent of the celebration over Worley’s NCAA-record 14 interceptions, although the College Football Hall of Fame hasn’t forgotten.

As for the 1968 Huskies, they quickly faded into history after The Times summarized: “There wasn’t much to cheer about in 1968, but Husky fans found their outlet in Al Worley, one of football’s least likely-looking candidates, who soared above his apparent limitations to become the college game’s greatest interceptor of forward passes.”

“Like I said, I don’t think much about it much anymore, but I’m still proud of it,” Worley said.

———————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

3 Comments

Truly remarkable, and I had no idea.

As always, David, a great read.

thanks for the reminder. I saw all those home games since my grandparents had started taking me to Husky games in 1961 when I turned 10. I remember calling out “interception” on every pass headed in Al’s direction in ’68.

Al was also the hardest hitting DB in husky history. Ask Mel Farr!