By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Based on four decades of international achievement, George Pocock warranted induction into the State of Washington State Sports Hall of Fame in 1960, when HOF originator Clay Huntington, a Tacoma sportscaster and radio station proprietor, first called for elections. That Pocock didn’t make the cut for 55 years ranks among the more baffling oversights in Pacific Northwest athletic history.

A master boat builder and mentor to generations of Husky coaches and oarsmen, Pocock earned Seattle’s “Man of the Year” award in 1948. In 1966, he entered the National Rowing Hall of Fame. The Seattle Times in 1999 listed Pocock among the state’s top 25 most influential sports figures of the 20th century.

The New York Times usually reserves its lengthier obituaries for world leaders and cultural icons. But when Pocock died in 1976, the newspaper published a tribute to him that ran more than 1,000 words, probably a record for a builder of racing shells.

Pocock is part of a 2015 HOF class that includes former University of Washington and NFL quarterback Chris Chandler, ex-Husky and NBA star James Edwards, Olympic figure skater Rosalyn Sumners, women’s basketball phenom Joyce Walker, and John Owen, the late Seattle Post-Intelligencer sports editor and columnist.

Represented by his granddaughter, Katie Kusske, Pocock and his fellow inductees will be formally enshrined during a pre-game ceremony at Safeco Field Tuesday – nearly a century after Pocock provided the means for the University of Washington to capture its first national championship of any kind.

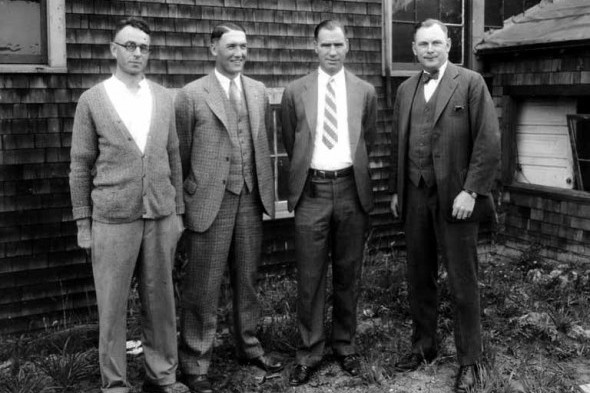

Pocock had been constructing unique racing shells for Husky crews on and off since 1912 when, in 1923, head coach Hiram Conibear recruited the Pocock brothers, George and Dick, to move to Seattle from their base in Vancouver, B.C.

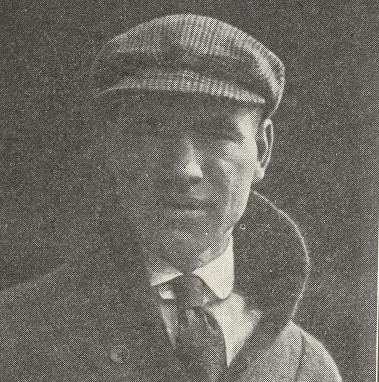

Born March 23, 1891, in Teddington, Middlesex, England, George Yeoman Pocock was the fourth child of Aaron Frederick Pocock and Lucy Vicars. Aaron toiled as a Thames boat builder, as had his father.

In 1901, Aaron went to work at Eton College and became boathouse manager in 1903. George and Dick signed on as apprentices and, over the next seven years, learned how to design superior racing shells. After Aaron lost his job in 1910 in an internal Eton political squabble, the Pocock brothers, unable to find work, decided to emigrate.

They considered Australia and New Zealand, but ultimately opted for Canada (they paid for the trip with prize money George won in a sculling race on the Thames), winding up in Vancouver on the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1911. There, they rented a floating shack on Vancouver Bay and set up shop.

But with no steady shell-building work available, Dick went into carpentry while George repaired boats at the Vancouver Rowing Club before taking a logging job. He later found work in a sawmill and shipyard.

Eager to employ their shell-building skills, the brothers caught their first break in 1912 when they were commissioned to manufacture a pair of single sculls for the Vancouver Rowing Club. Their work on that job, which netted a reported $200, soon attracted additional orders, including three four-oared practice shells for the Lake Okanagan Rowing Club, two four-oared shells for Victoria’s James Bay Athletic Club, and a four-oared shell for the Prince Rupert Rowing Club.

At that point, Conibear arrived from Seattle, ordered 12 eight-oared shells, and told the brothers he wanted them to move their operation to a former Japanese teahouse on the Washington campus originally built for the 1909 Alaska-Yukon Exposition.

Despite initial misgivings, the Pococks accepted, only to discover Conibear had the funds to pay for just one shell, not 12. With that, Dick went to Seattle to build it – the shell was ultimately christened The Rogers — while George remained in Vancouver.

In 1917, the year of Conibear’s premature death (he fell out of a plum tree and broke his neck), the Pococks, uncertain about the future of UW rowing, accepted positions with William Boeing’s Pacific Aero Products, forerunner of the Boeing Airplane Co., to build pontoons for Model-C seaplane trainers ordered by the U.S. Navy. The Pococks remained with Boeing through 1922, building racing shells as a side business.

That year, Yale hired Conibear’s replacement, Ed Leader, as its head coach. Leader, a part-time bouncer at a downtown Seattle “Dime-A-Dance” nightclub, tried to lure George to New Haven. When George declined, Dick took the job.

Rusty Callow, a varsity crew member under Conibear, succeeded Leader at Washington, enlisting George to build an eight-oared shell. George agreed on the condition that Washington provide him adequate working space. Callow had a loft constructed for that purpose in a seaplane hangar UW acquired from the U.S. Navy in 1920, and George left Boeing.

George constructed his first shell, christened Husky, entirely by hand and had it ready in time for the 1923 Intercollegiate Rowing Association (IRA) Regatta on the Hudson River in Poughkeepsie, NY. Callow’s crew, runner-up in 1922, thrashed Navy in the four-mile race, giving Washington its first national championship in what was considered an unprecedented upset. Along on the trip, Pocock made vital connections with East Coast coaches that paved the way for the shell-building monopoly Pocock would hold in the coming decades.

Up until 1923, eastern schools dominated the IRAs. But Callow’s crews repeated in 1924, placed second in 1925, and won again in 1926, all in Pocock boats. Those victories made Callow a coach much in demand. In 1927, he left Washington for the University of Pennsylvania (Washington couldn’t match Penn’s offer of a $10,000 raise). Those victories also made Pocock’s boats highly desirable and soon he was so flooded with orders from all over the country that he had to hire apprentices to keep up with the demand.

All of the top Eastern crews, including Yale, Penn, Cornell, Columbia, Navy, Harvard, Princeton, MIT, Wisconsin, Syracuse and Brown, ultimately purchased Pocock shells. So did Washington’s arch-rival on the West Coast, the University of California. At one point, 80 percent of all collegiate crews raced Pocock shells.

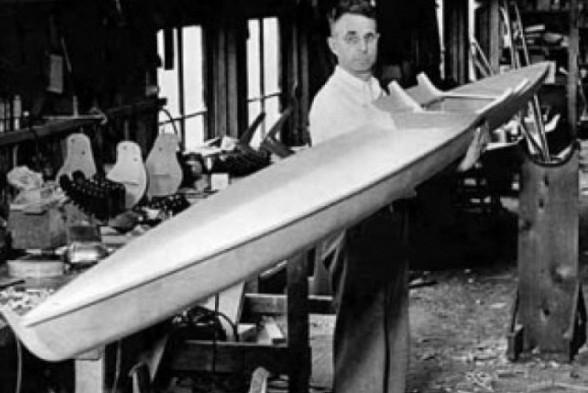

By the mid-to-late 1920s, with Pocock having experimented with a variety of woods and having devised new methods of shell construction, his boats, now constructed primarily of western red cedar (“the wood eternal,” according to Pocock) began to dominate and even monopolize intercollegiate regattas.

At the 1930 IRA Regatta, every shell in the competition was Pocock’s. In 1936, 19 of the 23 boats were Pocock’s. Washington won the 1936 eight-oared race in Pocock’s Husky Clipper, a prelude to its gold-medal victory at the Berlin Olympic Games, an event triumphantly chronicled by author Daniel James Brown in The Boys in the Boat.

At the 1948 Olympics in London, a four-oared shell built by Pocock, the Clipper Too, defeated Switzerland and Denmark for the gold with Pocock also serving as the crew’s coach at the request of oarsmen Warren Westlund, Bob Will, Bob Martin, Gordon Giovanelli and coxswain Al Morgan. In the eight-oared race, California, also in a Pocock shell and coached by Washington graduate Ky Ebright, won gold, defeating Great Britain and Norway.

Four years later, at the Summer Olympics in Helsinki, Pocock built all shells and oars used by the American team. The two-oared coxless powered by Rutgers took a gold medal, a four-oared shell from Washington won bronze, and a Navy crew coached by Callow, won the eight-oared gold, defeating the Soviet Union and Australia.

Pocock built seven shells for the American crews that competed in the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne. The U.S. won six medals in seven races, including three golds, the double-oared coxless, the double-oared coxed and the eight-oared race, in which Yale beat Canada and Australia.

Rowing Pocock shells, American crews also won Olympic gold medals 1960 and 1964. In addition, Pocock built shells for the Culver Military Academy, Old Dominion Club of Virginia, Buffalo Rowing Club, Wyandotte Boat Club of Detroit, Cuban and South American rowing clubs and the Buenos Aires Rowing Club, among many others.

“One of his greatest personal triumphs came on the day when an order arrived in his shop for a western red cedar shell to be delivered to Oxford University for use in the upcoming Boat Race against Cambridge,” Brown wrote in his best-selling book.

Another triumph: Navy fashioned a collegiate-record 31-race winning streak using shells crafted in Pocock’s shop.

“Others imitated Mr. Pocock’s designs, but rowing coaches insisted that Pocock shells went faster and stood up better,” The New York Times wrote following Pocock’s death at 84 in 1976. “This was a result of the technique that Mr. Pocock had learned as a boy in his father’s boat shop in Teddington, England.

“Among Pocock’s innovations were lightweight oars, special oarlocks, sliding seats and a special steering apparatus combining a fin and a rudder. The latter invention, placed directly under the coxswain’s seat in place of a tiller at the stern, enabled the coxswain to steer by a rudder post with his hands or, in an emergency, with his knees.

“Pocock’s oars were made of two hollow shells around a solid core and skillfully joined four pieces of wood. He used Sitka spruce from British Columbia for the keels and gunwales of the shells. Pound for pound, this wood is tougher than steel. An even harder wood, Australian ironbark, was used for the track upon which the seat rollers move.

“The seats, of Idaho white pine, gave the oarsmen a mechanical advantage by allowing them to get their legs into a stroke. Also, the shift in weight allowed by the sliding seats helped propel the shell. In applying the planking, or din, Pocock used red cedar. The rudders were made of wild cherry or Honduras mahogany. With a Pocock shell, a heavyweight crew could attain a speed of 15 mph.”

Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, Pocock typically attributed victory not to the superior boats he built but to good crews, good coaching and outstanding mentorship. That was Pocock’s nature, according to his granddaughter, Katie Kusske.

“My grandfather was a very soulful man, very quiet outside his shop,” she said. “When it came to his boats and the crew and the coaches, he was very thoughtful. He loved having a positive influence.”

Early in her life, Kusske worked in Pocock’s shop and got to see how her grandfather went about his business.

“He would have his Wheaties in the morning and would go to the shop, where he thrived on creating each and every boat singlehandedly. Each boat was like his child, and he put his heart and soul into every one. His aim was build the perfect boat. He would perfect, perfect, perfect. That’s what he was put on this earth for, the boat building and the mentorship.”

“It’s a great art, is rowing. It’s the finest art there is. It’s a symphony of motion and when you’re rowing well, why it’s nearing perfection. And when you near perfection, you’re touching the divine. It touches the you of you’s, which is your soul.”

Those are Pocock’s words, and Kusske says she can only imagine what went through her grandfather’s mind when he watched national and international regattas rife with shells he had painstakingly constructed.

“It must have been an overwhelming feeling of pride and joy,” Kusske said. “I’m not sure that was the ultimate validation for him, but I could not imagine the sense of pride and joy. Imagine creating something yourself that is one of a kind, and immaculately and precisely made and watching the crews develop an emotional bond with it.”

Many over the years have labeled Pocock a genius. Kusske was too young when she worked in his shop to recognize that, remembering him mainly as a quiet, deeply religious man devoted to his church and family and to the young men who came to bond with the shells he created.

“I would see the various stages (of boat building), but I wish now I could take myself back and seriously stop and watch him, with that pencil in his pocket, wearing that apron. I didn’t think of him as a genius, only as my grandfather. Now I wish I could get inside his brain and go through the process with him.”

A fuller appreciation of Pocock, meticulously detailed in The Boys in Boat, leaves the impression that perhaps no individual ever did his or her job better than Pocock did his.

“There was something he took away from working with his father way back when he was an apprentice. He had a gift and never grew tired of building boats,” said Kusske.

Nobody knows now exactly how many shells Pocock built in a career that lasted until 1975, when he crafted his last one. According to the Pocock Rowing Center, records are incomplete, but a “best guess” is that the number is in “the tens of thousands.”

Each a masterpiece.

—————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

my father in-law just got a fantastic gold Cadillac CTS-V Coupe just by part time work from a home pc…

view website

see this web-site

———————————————————————————————————–