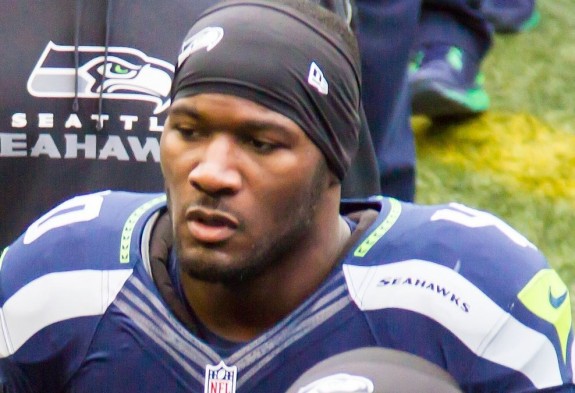

If I were asked to choose a Seahawk least likely to create another national social-issues firestorm for the NFL, Derrick Coleman would be at, or near, the top of the list. A personable, polite, low-key guy, Coleman had the pro football nation at his feet in the run-up to the Super Bowl in New York after his triumphal story about prevailing in pro team sports despite being deaf.

Now Coleman’s story takes a grim turn.

Coleman’s Oct. 14 auto accident that injured another driver and caused the Seahawks to suspend him for a game has blown up this week into a public fight between the Bellevue Police Dept. and Coleman’s fiery attorney, Stephen Hayne of Bellevue.

In a rare press conference at police headquarters in Bellevue Tuesday morning, Chief Steve Mylett blasted Hayne’s claim that the release of some of the department’s information in a 101-page report of the investigation was intended to defame Coleman.

“He’s questioned our integrity, our ethical behavior and our professionalism,” Mylett said. “His assertions are baseless and offensive. Our officers have been professional, methodical and complete.

“His claim that we released documents in some sort of effort to defame his client’s reputation . . . When he does that, for the goal of salvaging his client’s reputation, he shouldn’t be doing that to this police department . . . he crossed the line.”

Reached by phone, Hayne, who said he hadn’t seen the live stream of Mylett’s remarks by local TV stations, was defiant.

“The Bellevue police department is trying to tar Derrick Coleman, and they’re doing it successfully,” Hayne said. “They’re trying him in the court of public opinion, to try to make themselves look better and him look worse, like he’s some sort of thug who deserves condemnation from the public.

“They should know better.”

The crux of the matter for Hayne is that information has been released prior to charges being filed, including items found in a search of Coleman’s truck, which struck another eastbound motorist on SE 36th Street and caused the Honda Civic to flip on its top. The list included cannabinoid drugs and paraphernalia, as well as a 10mm pistol clip, that were unrelated to the charges recommended to the King County prosecutor’s office — felony hit-and-run and vehicular assault.

Hayne also contends that there is no video or audio record of the report’s claim that Coleman said he smoked spice in the hour before the accident. Nor is there evidence of illegal drugs in the blood tests administered six hours after the accident.

“We agreed to do the blood tests immediately (at the jail), but they said they wanted to wait for a judge’s order, which was all right,” Hayne said. “There is no evidence he ingested spice, nor is there evidence he said he did. And if he had any illegal drugs, why are there no charges of possession?

“The city of Seattle and other communities are making use of video and audio recordings. Are you telling me Bellevue can’t afford it? In a 1o1-page manifesto, they have nothing to back it up.”

At the press conference, Mylett said his department was complying with state law regarding the release of public information, both at the time of the accident as well as Monday, when the report and recommendations were released.

Of the negative blood tests for drugs, Mylett said, “Toxicologists tell us spice is the most difficult to test for,” and the absence of drug-possession charges was because “I believe” the drugs in question are not illegal in Washington, although they are illegal under federal jurisdiction.

Mylett also defended the delay in releasing the report, saying, “This is not unusual, the length of time that it took to complete this investigation,’’ and also dismissed the claim that the report’s release was delayed until after the season was over to please the Seahawks.

While he said that “12” banners are visible throughout the police offices, the possibility of favoritism toward the Seahawks was “absurd . . . we have no motivation to manipulate any investigation for any group, any individual, period. We wouldn’t do that.’’

I asked Hayne that if there was no evidence of drug use, what caused the accident. He replied that he couldn’t discuss it because he will be identified as a witness for any trial ordered by the King County prosecutor, since Hayne recorded the accident-day video below and administered blood tests. He will turn over Coleman’s defense to others.

Aside from the did-too, did-not argument in Bellevue, the saga will also pull another non-football, American culture story from the the margins to the spotlight, as only the NFL can: The use and abuse of street drugs that often are not illegal but are often far more hazardous than the misleading, generic “synthetic marijuana” label.

The Coleman episode involving spice was the second this month publicly for an NFL player. New England’s Pro Bowl DE Chandler Jones showed up Jan. 10 at the Foxborough police station behaving erratically and seeking help. He was briefly hospitalized, released and returned to practice the next day. The Boston Globe reported an anonymous source saying his behavior was due to a bad reaction from synthetic marijuana use.

No charges were filed. According to rule 1.4.1 in the NFL’s policy on substances of abuse, a player will enter into stage one of the NFL drug-testing program if he gets a citation for using synthetic marijuana.

But if police in states such as Washington have no legal grounds to act on cannabinoids, not much can be done about substances that the National Institute on Drug Abuse says “may affect the brain much more powerfully than marijuana; their actual effects can be unpredictable and, in some cases, severe or even life-threatening.”

Ironically, it may be the NFL’s own drug policy that is pushing players, however unintentionally, to using cannabinoids. Regular marijuana is on the NFL’s list of banned substances of abuse, even though 20 states have approved its use as medication. While certainly some players use pot recreationally to get high, others use it to self-medicate chronic pain because they fear the consequences from opioid painkillers and the threat of addiction.

A segment being re-run at 10 p.m. Tuesday on HBO’s “Real Sports” discusses the widespread, clandestine use of marijuana in the NFL with former Broncos TE Nate Jackson, who admits he “weeded when needed” during his playing days from 2003 to 2008. The trailer is below:

However the Coleman case plays out, pro football has again illuminated for mainstream consumption another disturbing aspect of American culture that it reflects, but did not create.

Below is a video produced in September by the New York Daily news on the consequences to the Big Apple’s street life of cannabinoid use, specifically a version called K2:

18 Comments

Man, do NOT spring auto-play audio clips on us! They’re bad enough on the whatsleftofthePI.com. When I have my head-bangin’ speakers turned up to 11 I do NOT need a growling 30 hZ surprise from K2!

Thank yuh vurry mush.

Sorry about about the autoplay. I was hoping the vid was worth it. No?

With a warning, maybe, but I got outta there ASAP. C’mon, If you don’t let me know, auto-play it and I go.

Oh, and that pot thing? I got this — since 1966. http://tinyurl.com/qdrsxw3

So the perp on that link is a guy I’ve heard of. Rumor was he was locked up long ago in the Institution for the Perpetually Misunderstood. Must be nearing parole by now . . .

This is what I love about sports. The stories illustrate and amplify real life so well. The synthetic pot does not have a drug test at all. That is why an NFL player would use it. Coleman was impaired–if not he is the worst driver on earth and needs his privileges suspended.

I’m as eager as you to learn from Coleman what he claims happened, beyond the video produced after the accident.

It seems out of character for Colman, but he damaged some property. I also would like to hear his full explanation . . .

My experience is that what the clubs like us to see on the surface is much unllke the depths.

The smarmy attorney is trying to focus on the recreational and relaxation drug. He’ll later try to get that evidence thrown out of court by a 12 judge. And only then, he will focus on shifting blame to the woman and vehicle which ended upside down way up the hill. Everyone can see she caused this accident.

Remember, only within a court of law is a perpetrator considered innocent before proven under certain rules guilty. The rest of us are free to think as we see fit. GUILTY!

Keep this comment in mind, Reeb, should you ever need an attorney’s help to get you out of trouble. They’re all smarmy until you need one, right?

why do you hate america?

chief mylett hasn’t learned that the lesser seattle way is to keep things on the down low while quietly stabbing your adversary in the back when he’s not looking. i think i might like this guy.

Sort of Trumpian style, yes?

without the lies and the fascism hopefully.

thanks for the thorough article, art.

What? No wisecrack?

The Bellevue police chief claims his department is professional and methodical. Does ‘professional and methodical’ include being drunken asses at a pro sports venue? The chief is posturing. So’s the lawyer. Perhaps they both should STFU and let the courts deal with this, as it’s supposed to be?

Oh, and Art–I’m with bugzapper. Can’t stand, and won’t tolerate, autoplay videos. I often read SPNW at work–the audio is unwelcome to all.