Dads, sons and ball.

If Field of Dreams didn’t clearly explain the power therein, Sunday in Cooperstown, NY., wrote it plainly in salty streams down 100,000 cheeks. My guess is the tide ran high in homes who watched on MLB Network, too.

In their induction speeches at the Hall of Fame ceremony, Ken Griffey Jr. and Mike Piazza reached some touchstones that were more intense and intimate than any euphoria that followed their baseball deeds.

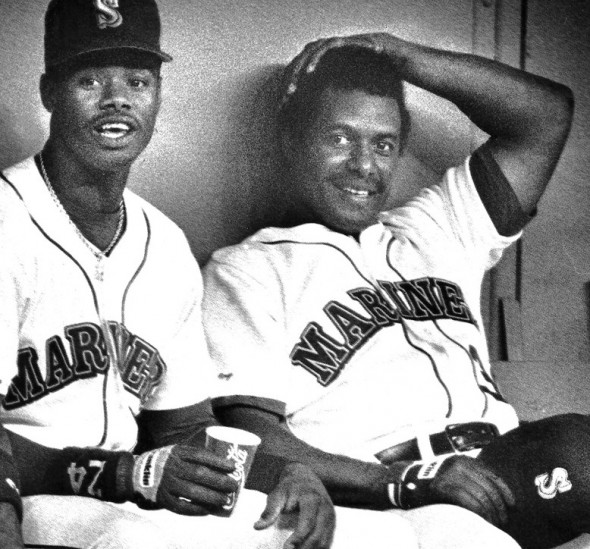

To this day, and likely forever, the moments that had Griffeys Senior and Junior in the Mariners outfield remain among the most incredible in sports history. If they had just stood there, it would have been enough to unleash the ducts.

But in September 1990, Senior, 40, and Junior, 20, hit back-to-back homers against the Angels in Anaheim, an episode so mathematically and generationally preposterous that the first flying hippo would take second place in the Absurdity Matrix.

Junior made only passing reference to it Sunday. Instead, as Senior, sitting in the audience of families, hung his head and wept, Junior spoke of a more important feat.

“He taught me how to play this game, but more importantly, he taught me how to be a man,” said Griffey, who failed hopelessly and delightfully his pre-speech prediction of coolness. “How to work hard, how to look at yourself in the mirror each day, and not worry about what other people are doing.

“Baseball didn’t come easy for him — a 29th-round draft pick who had to choose between football and baseball. Where he’s from in Donora, PA., baseball is the game. I was born five months after his senior year. He made a decision to play baseball to provide his family, because that’s what men do. I love you for that.”

As Griffey grew into a prodigy, there were long absences and some high tensions between a stubborn dad and an often-insecure son. None of that mattered Sunday as Griffey, teary but resolute, addressed a crowd of more than 50,000, said to have been the second-largest gathering in the history of the annual ritual.

“I got a chance to play with my dad,” he said. “I got to yell at him and tell him to get a hit. In baseball, people call each other fossil, graybeard, grandpa, dad, pops.

“But I got a chance to say it and mean it.”

The Piazza tandem seemed even more overwhelmed, probably because their origins story is more unlikely. He is the lowest draft choice to make the Hall — 62nd round of the 1988 draft — and Vince Piazza was a relentless and sometimes controversial figure in his son’s career.

Vince wept openly as his son’s halting speech offered deep gratitude.

Claiming his father’s faith in his son’s abilities was greater than his own, Piazza said, “We made it, dad. The race is over. Now it’s time to smell the roses.”

Sentiment this day was not confined to the heaviness of parental bonds. Griffey told some tales, including one with his oldest son, Trey, now a senior wide receiver with the University of Arizona, but earlier in his youth a harsh television critic.

Father and son were watching TV when Trey picked up a bat and struck the set. Griffey’s wife, Melissa, was furious, even more so with her husband for not being upset too.

“Girl, you can’t teach that swing,” he said, laughing. “I got up and bought a new TV.”

The three biggest cheers from the healthy Mariners contingent who made the cross-country trek were not surprising.

Griffey made a pitch for the baseball writers to get busy voting Edgar Martinez to join him: “Yes, he deserves to be in the Hall.”

He also saluted Jay Buhner as “the greatest teammate I ever had. A guy that gave everything on the field and always spoke the truth, even if you didn’t want to hear it. I love you for that.”

Martinez, playing hooky from his day job as Mariners hitting coach — they lost, 2-0, in Toronto — and Buhner were in the audience. He had something for the Seattle fans not in attendance.

“From the day I got drafted,” he said, “to my first at-bat at the Kingdome, to the 1995 playoffs, to my first return to Seattle with the Reds, to my return to Seattle, to my retirement in 2010, Seattle, Washington, has been a big part of my life.

“So many great things we could talk about. Out of my 22 years in the majors, I learned only one team will treat you the best, and that is your first team. I’m damn proud to be a Seattle Mariner.”

And then he reached under the podium for a baseball hat, put it on backward, and said thank you.

The deed and the words prompted riotous acclaim from the assembled.

Griffey now belongs to the baseball immortals. But they get his legend.

Senior and his ex-wife, Birdie, get the credit. And Seattle gets the glory of being the playground for one of the most glorious athletes in sports history.

Seattle is damn proud, too.

6 Comments

Art, as fans, sports writers, pundits, sports talk jocks, team mates and current players who idolized him while growing up, and those in the M’s organization who made it happen from Lincoln on down, this was probably our best day in baseball so far. And it wasn’t just another HOF’er. It was our guy, one of the best, if not the best EVER.

BUT…The sun has not yet set. Has it? As Jr. said today, and Randy said it last year, Edgar belongs here.

<<o. ★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★✫★:::::::!be190p:….,…..

That is quite a statement, saying that nothing on the field matches an award and Griffey talking.

You sure?

It’s amazing and special how the Griffey family has become so strongly linked to Seattle baseball history. They’re right up there with the Hawes, Huards and Tuiassoppo’s. I was there for Senior’s first game as Mariner. Still have my ticket stub The entire Mariners dugout was energized The Kingdome practically exploded when Senior threw out Bo Jackson at second base and you’d feel the emotion seeing father and son running out to the outfield together.

It seems almost appropriate for Junior and Mike Piazza to go in together. Both were drafted in the same year on opposite ends of the draft. Both were on the cover of Sports Illustrated at the height of their careers. Now both go into the HOF together.

When all is said and done Ichiro will be next. And he too will say that Edgar belongs in the Hall.

I fear Edgar is doomed by writers who think DH is not a position. Imagine pro football writers saying punter is not a position.

I believe that Edgar will get in but by a special committee vote. Once he gets in then other DH’s will finally follow. But someone needs to get past the prejudice in order for the HOF to move forward on this. A committee vote will be needed to break that barrier.