The Tacoma Rainiers and Benjamin Bradbury Cheney’s namesake ballpark, Cheney Stadium, host the 30th anniversary Triple-A All-Star Game — Pacific Coast League vs. International League — Wednesday night (MLB Network, 6:05 p.m.). Neither Tacoma, the longest-tenured PCL city, nor the Rainiers, the Mariners’ AAA affiliate since 1995, have been involved with an event quite on the scale of this one.

“This will be huge showcase for not just Cheney Stadium and the Rainiers, but for the entire region, and we’re excited to show it off,” Rainiers president Aaron Artman declared a year ago when Tacoma was awarded the game.

Among other things, the Triple-A All-Star game provides a convenient segue into the particulars of the man most responsible for professional baseball’s existence in Tacoma. Cheney’s life was rife with remarkably generous deeds after humble beginnings as a dirt-poor kid from South Bend, Pacific County.

By all accounts, Cheney would have preferred to channel his considerable energies into a career as a baseball player. But he was 5-foot-8 and had an almost genetic aversion to hitting a curve ball. But for a man who couldn’t wield a bat effectively, Cheney sure knew what to do with a hunk of wood.

He became a timber baron and philanthropist who not only affected the lives of thousands of young Northwest athletes in a positive way, but – it’s not too far-fetched to say so — the lives of every American born after 1945.

To cite just one of his many acts of largesse, if not for Cheney . . . well, instead, let’s run the numbers: He backed financially 230 amateur sports teams that included more than 5,000 players. The elite of these captured a combined 42 league championships, nine state and regional championships, and one national American Amateur Baseball Congress and four CSABA crowns. Without Cheney’s willingness to crack open his wallet, none of this would be part of the Northwest’s rich sporting lore.

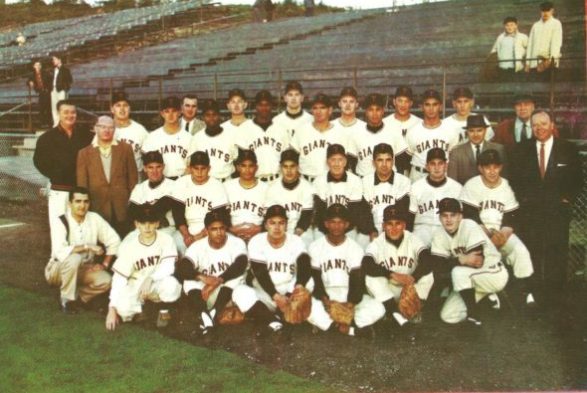

All those titles and all those players performed under the collective banner of “The Cheney Studs,” or “Cheney Seattle Studs,” and sometimes the “Tacoma Studs.” They were baseball, football, basketball, hockey and soccer teams, as well as bowling teams whose participants ranged from nine years old to adults. The Cheney Studs also included women.

All were able to play because Cheney paid for their equipment, uniforms and travel — whatever the athletes required.

In 1959, five years after he began bankrolling his regionally prominent senior amateur baseball and basketball teams, Cheney supported five juvenile baseball teams in Tacoma, an adult team in Seattle and Pee Wee teams in Greenville and Arcata, CA., where his Cheney Lumber Co. operated mills. Cheney also supported four Tacoma football leagues that included Rookie, Pee Wee, Bantam and Midget teams.

Cheney’s elite athletes, 16- to 22-year-old young men, came from Northwest colleges and high schools and played in Seattle’s top amateur leagues, which were a big deal in a city years away from hosting major league sports. Cheney’s aim: Give athletes an opportunity to develop their skills so that they have a chance to advance to the professional ranks.

His robust philanthropy stemmed from his experiences as a youth. Born March, 24, 1905, in Lima, Beaver Head County, MT., Cheney’ was moved at nine to South Bend, famous for its oysters and alive with sawmills.

His mother, Martha Kidd Cheney, had just died in a Pocatello, ID., hospital and his father, John, opted to remain in Montana after he quickly remarried. Young Ben and his sister, Lulu, grew up on Willapa Harbor in utter poverty, reared by their grandparents, Benjamin Franklin and Rebecca Cheney, who moved to South Bend to open a photography studio.

As a young man, Cheney came into contact with a juvenile baseball program operated by Father Victor Couvorette, a Catholic priest who sponsored South Bend’s teenage team. Father Couvorette purchased uniforms and equipment for the boys and even provided streetcar fare to get them to their games in nearby Raymond.

Couvorette encouraged Cheney’s love of baseball and all sports. Cheney played football, basketball and baseball at South Bend High for two years before quitting so he could “get on with my life.” Determining that South Bend held no future for him, Cheney borrowed money so that he could make his way to Tacoma, where he went to work for a string of lumber companies and tried his hand at baseball in one of Tacoma’s commercial leagues.

“I only got to play because I could catch and throw, and I always showed up,” Cheney once told The Seattle Times. “Until I was almost 30, I kept trying to make contact with a breaking pitch. It wasn’t any use.”

As Crow’s Lumber Digest noted in a July 30, 1959 article on Cheney, his early lumber experience occurred in South Bend, where, during summer months, he worked as a whistlepunk (a lumberjack who operates a signal wire running to a donkey engine whistle) and helped load rail cars for Columbia Box & Lumber, among other companies.

Once in Tacoma, Cheney, “too poor to buy a streetcar token,” according to the Pacific County Historical Society, scraped together enough money from odd jobs to pay his tuition at Knapp Business College. After nine months, he went to work as a 19-year-old stenographer at the Dempsey Lumber Co. for $85 per month.

After receiving a basic education in the business, Cheney joined the Fairhurst Lumber Co. in 1929, primarily as a wholesaler. In that capacity, Cheney worked for many small mills from northern California to the Canadian border.

“An early practice was to purchase small tracts of timber, some for as little as 50 cents per thousand, and then turn the logs over to small mills for cutting,” noted Crow’s Lumber Digest. “From this, Cheney eventually became the biggest individual supplier of ties to the continental railroads. He began shipping ties to England, South America and China. It was while he was cutting railroad ties that he got an idea.”

By May 1936, with the country wallowing in the Great Depression, Cheney saved $14,000 and quit Fairhurst to start his own company. But it was not successful, the initial Cheney Lumber Co. losing $111.86 in its first two months and $511.96 in its first year. Cheney sought loans to keep his business afloat, but in a collective decision they would later regret, all of Tacoma’s banks turned him down.

“Times were changing,” The Tacoma Historical Society wrote of this period. “It was becoming more difficult to obtain cheaply the small tracts of timber in which Ben and his tie producers set up their portable mills, and the side-cut slab wastage was enormous, often two-thirds of the log.

“What to do with the slabs baffled Cheney. Broom handles? No. Fence posts? No. Lath? No. Toothpicks? Of course not. The solution came to Ben in the middle of the night: Why not supply the housing market with standard eight-foot (wall) studding, the same length railroad ties were cut. Many ceilings then were eight and a half feet, and builders were taking any length stud they could get, often 10 or 12 feet. The waste was enormous.

“After that, Ben couldn’t sleep for thinking of the whole thing. He bought a squarehead Berlin planer from an old mill at Mukilteo for $200, and traded the scrap from another mill for an edger. Thus was born the first Cheney stud mill at National, WA., near Eatonville.”

In the lumber trade, Cheney’s eight-foot pieces had traditionally been called “shorts.” A skilled marketer, Cheney conceived of a new logo that he ultimately stamped on each stud, using the silhoutte of a Belgian stud horse he had seen at the Puyallup Fair. Cheney also had all of his two-by-four ends painted red for identification purposes. Thus was born the Cheney Stud.

“The new product soon established the standard room height in residential construction throughout the United States,” explained the Tacoma Historical Society. “It put to use an enormous amount of formerly wasted timber, incidentally saving American homeowners uncounted millions of dollars in heating expense by reducing the height of their ceilings.”

The first boatload of Cheney Studs departed Willapa Harbor in 1945. By 1959, Cheney’s mills inWashington, Oregon and California — Tacoma, Medford OR., at Myrtle Point near Coos Bay OR., Central Point OR., Arcata, Pondosa and Greenville CA. — were processing 100 million board feet of timber per year. In each of the towns in which he conducted business, Cheney sponsored amateur sports teams.

At the urging of a curmudgeonly youth coach named Joe Budnick, Cheney began sponsoring senior amateur baseball and basketball teams in 1954, outfitting his “Cheney Studs,” previously known as the “Rainier Hi-Stars,” with uniforms and equipment and paying meal, travel and hotel expenses.

Budnick, once a three-sport star at O’Dea High School who played football briefly at the University of Washington and dabbled in basketball at Seattle University, recruited the players, drawing many from Northwest colleges and several each year from local high schools.

The baseball Studs played in Seattle’s City Amateur League and enjoyed an immediate burst of success after Cheney began his sponsorship. The 1954 Studs won both the city and state amateur championships, captured a regional tournament in Watertown, SD., and played in the American Amateur Baseball Congress national tournament in 1954 in Battle Creek, MI.

The Studs returned to Battle Creek in 1955 and placed second. After another second-place finish in 1959, the Studs, with Budnick still managing, won the championship in 1960. The story of the win prompted big headlines in Tacoma and Seattle newspapers.

Many who donned Studs flannels played professionally after “graduating” from the organization. Several spent time in the major leagues, notably Tacoma’s Ron Cey, who had a 17-year career with the Los Angeles Dodgers and Chicago Cubs and made six National League All-Star teams.

More recently, in 2004, Tim Lincecum, then a University of Washington student, spent a summer with the Studs (won two games in the amateur World Series). He later won a pair of Cy Young awards while pitching for the San Francisco Giants.

Cheney not only sponsored sports teams, he backed a number of sports-related spinoffs such as the Cheney Stud Courteers, a basketball troupe which for a number of years entertained crowds at high school and college basketball games with Harlem Globetrotter-style halftime shows. The Courteers, its members 12 to 15 years old, once performed during a Seattle SuperSonics game.

In 1959, a year after the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants relocated to the West Coast, Cheney learned that a small stake in the Giants was up for sale and wasted no time buying it. Within months, Cheney discovered that an even larger block of Giants stock was available due to the fact that New York socialite Joan Whitney Payson had to dispose of her holdings so that she could purchase an interest in the expansion New York Mets.

Cheney bought Payson’s stock and suddenly owned 11 percent of the Giants franchise, making him the club’s second-largest stockholder behind Horace Stoneham.

As an owner and board member, Cheney learned that the Giants were looking for a new location for their AAA team, then playing in a seedy facility in Phoenix. The Giants wanted the team relocated by 1960 and Cheney proposed Tacoma, the only problem being that Tacoma did not have a AAA-worthy ballpark.

At Cheney’s urging, the City of Tacoma and Pierce County came up with $900,000 to construct a stadium. Cheney offered to cover $100,000 in cost overruns, figuring there would be overruns. Sure enough, there were, about $100,000 worth. But the major challenge was that the facility had to be built quickly.

Construction began in January 1960 and was completed in 42 working days, an astounding feat overseen by Cheney, and the main reason why the stadium was named in his honor. The successful rush to build enabled Tacoma to join the Pacific Coast League in 1960. A year later, the Tacoma Giants won the PCL pennant.

Cheney Stadium has since hosted other AAA affiliates of MLB teams: Twins, Cubs, Yankees, Tugs, Timbers, Tigers and since 1995, the Rainiers.

A grinning, life-size bronze statue of Cheney, complete with scorecard and peanuts, occupies a front row seat – Row 1, Section K — in the grandstand at Cheney Stadium at 2502 S. Tyler St. The statue was part of a $30 million remodel, funded by the city and completed in 2011.

Cheney won numerous awards, including induction into the Tacoma-Pierce County Sports Hall of Fame in 1968. But he never lived to see his statue in his namesake ballpark, nor did he live long enough to experience his induction into the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 2004.

Cheney’s heart gave out May 18, 1971. But it pumped generosity to the end, and beyond. A few months before his death, Cheney was instrumental in making possible a trip by Tacoma’s Wilson High School to Honolulu to play a Thanksgiving Day football game.

Weeks following Cheney’s death, one of his soccer teams, the Cheney Stud Hustlers, traveled to England for a series of exhibition matches. Cheney footed the bill.

Five years before Cheney brought the Giants to Tacoma, he quietly established the Ben Cheney Foundation, a charity aimed at encouraging growth and prosperity in the logging communities where the Cheney Lumber Co. was active, including Tacoma, southwestern Washington, southwestern Oregon, and portions of Del Norte, Humboldt, Lassen, Shasta, Siskiyou and Trinity counties in California.

Cheney’s generosity outlived him. When the Cheney Lumber Co. was sold to Louisiana Pacific, an additional $10 million went to his foundation.

“Men with Cheney’s dedication to helping others don’t come around too often,” columnist Earl Luebker of the News Tribune wrote after Cheney’s death. “Tacoma is a much better place for his having passed through here.”

“At least where Ben is now,” added Times baseball writer Hy Zimmerman in his story on Cheney’s passing, “there are no curve balls.”

2 Comments

Steve —

FANTASTIC piece on Ben Cheney, timed wonderfully with the AAA All-Star Game coming to Tacoma. Such an inspiring story about Ben’s life. I was honored when the Cheney Studs “semipro” baseball team would let me serve as batboy when they played at Interbay (the valley between Queen Anne and Magnolia in Seattle) back in the day. My goal was to someday play for the Studs. Unfortunately, I suffered from the save malady as Ben when it came to hitting curveballs — or virtually any other pitch, now that I think about it. There’s a reason why I became a 5-foot-7, 130-pound relief pitcher at Eastern Washington …

Howie Stalwick

Goodonyer, Howie. Steve did a great job on this. Hope all is well.