By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

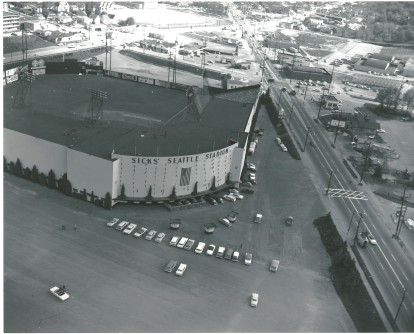

Former colleague/collaborator Dan Raley, whom we cited in last week’s Wayback Machine: Seattle U. shocks Globetrotters, makes a brief, one-paragraph mention in his latest non-fiction gem, Pitchers of Beer (due out soon from the University of Nebraska Press, but now available on Amazon.com), of a Seattle Rainiers doubleheader on Aug. 27, 1961, against the Portland Beavers at Sicks’ Stadium.

This otherwise inocuous twin bill likely would not have merited inclusion in what promises to be the definitive history of the Rainiers had it not been for the Beavers’ subversive stunt of springing 55-year-old (age disputed) Satchel Paige on the the local nine in the seven-inning nightcap.

Paige had not pitched in an official minor league game since 1958 (Miami Marlins, International League), nor in a Major League contest since 1953 (St. Louis Browns, American League). So Portland’s decision to send him to the mound seemed curious to the Rainiers then, and also to us today — until we better understood Paige, his time, and the situation in which the Portland Beavers found themselves.

The Beavers had spent much of 1961, the year of the riveting Maris-Mantle home run race, fluctuating between fourth and eighth place in the Pacific Coast League standings. Although the gonfalon had eluded Portland’s grasp, on most days only five games separated the fourth-place team from the eighth-place club. With a little luck, the Beavers could finish in the first division instead of the second.

But the Beavers faced a larger problem. The previous year, 1960, they had attracted 116,000 fans to 77 home games, a bleak total. And although their 1961 attendance had ticked up, the franchise, which had once employed future Hall of Famers Dave Bancroft (1912-14), Harry Heilmann (1914), Jim Thorpe (1922) and Mickey Cochrane (1924), had been listing toward bankruptcy. Portland management convinced itself that a partial solution lay in the great and aging Satchel Paige, mainly as a wow factor.

Paige started his professional career in 1926, playing for the Chattanooga Black Lookouts of the Negro Leagues for $50 per month. Over the next two decades, he starred for eight Negro League teams, pitched in the North Dakota League, Dominican League, Mexican League, Cuban Winter League and California Winter League (in his autobiography, Paige takes credit for the spread of baseball in Latin America, saying, “I can honestly say I started baseball in the Latin American countries. I introduced it there, and look how it’s spread)”. He even logged a stint with the Harlem Globetrotters.

In the 1930s, Paige also toured with the House of David, a team fielded by a Michigan-based communal religious sect that had been barnstorming since the 1920s. The House of David claimed to have invented the game of “Pepper,” was probably America’s first integrated baseball team, and forbabe its male members to shave or cut their hair (when Paige hurled on behalf of the House of David, he did so wearing a fake red beard).

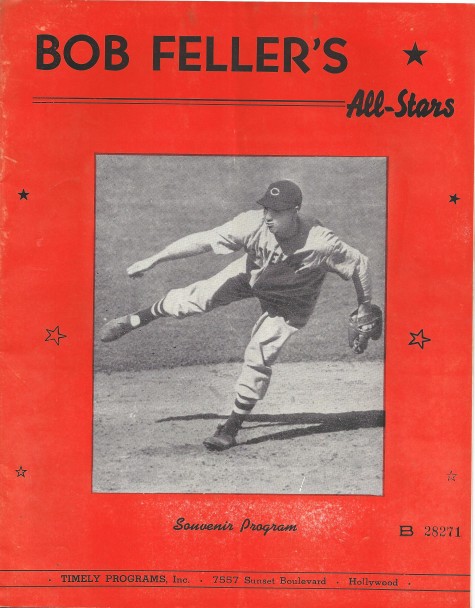

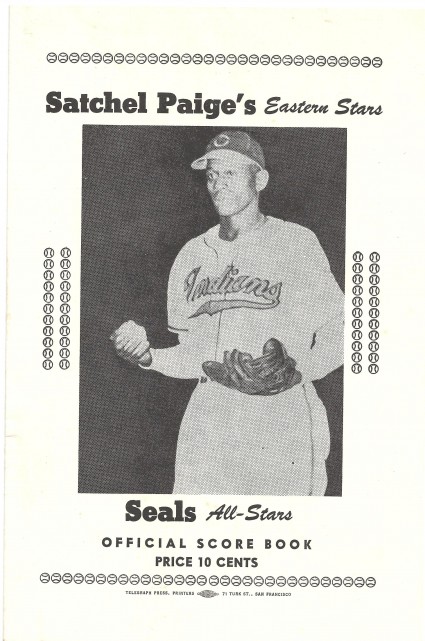

In the late 1940s, Paige barnstormed America with his own “Satchel Paige All-Stars,” often playing against the “Bob Feller All-Stars,” pitching in any towns that would meet his price, the very definition of barnstorming. Paige had no trouble playing with and against white players, nor did Feller suffer qualms playing with or against black players. For his part, Paige called it “putting a little dent in Jim Crow.”

Fanning out from his base in Kansas City, where he kept a wife and six kids, Paige drew throngs most everywhere, his popularity enhanced by his flamboyant nature. He often threw trick pitches and used double windups, causing him to become the subject of often-repeated folklore. Although many of his exploits are difficult to verify (Paige repeatedly offered conflicting versions of events), fellow Negro Leagues star Buck O’Neil famously said, “The stories about Satchel are legendary, and some of them are even true.”

Such as the one in which Paige instructed his outfielders to sit down in the ninth inning while he struck out the side. And the one in which Paige supposedly fanned Rogers Hornsby five times in a barnstorming game. In 1934 (and this has been verified), he pitched 13 innings against Dizzy Dean and won 1-0. (Dizzy won 30 games that year.)

Then this: On July 21, 1942, Paige intentionally walked two batters in the ninth in order to face Negro Leagues icon Josh Gibson with the bases loaded. Paige informed Gibson that he was going to give him three fastballs. Gibson saw the fastballs, but couldn’t hit them, striking out to end the game. Although no comprehensive documentation is possible where the Negro Leagues are concerned, Paige is reputed to have thrown 300 shutouts and 55 no-hitters.

Paige awed white major leaguers. Bob Feller would say that Paige was the best he ever saw. Hall of Famer Hack Wilson, who drank himself out of baseball and became the inspiration for manager Jimmy Dugan (Tom Hanks) in A League of Their Own (1992), added that Paige’s fastball looked like a marble as it crossed the plate.

As far back as the 1920s, Birmingham Black Barons owner R.T. Jackson took advantage of Paige’s popularity by “renting” out his pitcher for one or two games to other Negro League teams to help those clubs increase their attendance. Paige, in fact, spent most of the 1930 season “on loan.”

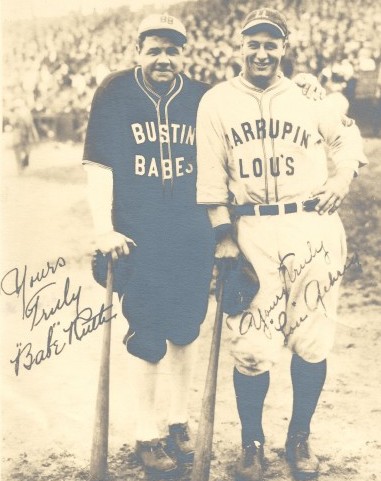

Because Major League Baseball did not integrate until 1947 (Paige made his debut as a 42-year-old “rookie” in 1948), Paige spent the majority of his career well under national radar, playing year around in various leagues and as a barnstormer. Many players, black and white, did that to supplement their then-meager salaries (free agency and arbitration were years away), including Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, all of whom played exhibition baseball in Seattle decades before Paige’s 1961 appearance at Sicks’ Stadium. Barnstorming did not really end until Curt Flood put an historical squash to it in 1970.

Paige barnstormed more than anyone, traveling as many as 30,000 miles per year. When Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck met Paige’s price in 1948, A.G. Spink opined in The Sporting News‚ “Veeck has gone too far in his quest for publicity. To sign a hurler at Paige’s age is to demean the standards of baseball.”

Despite that rebuke, Paige spent six years in the majors with Cleveland (in 1948, he became the first African American to pitch in the World Series) and the St. Louis Browns before returning to the minor leagues and his barnstorming tours, as a two-time American League All-Star. He spent the years 1959-61 with the Kansas City Monarchs, appearing in a reported 83 games in city after city as Maris and Mantle stole the national baseball spotlight.

On Aug 20, 1961, Paige was the winning pitcher and MVP in the Negro American League All-Star game in front of 7‚245 fans at Yankee Stadium. Two days later, on Aug. 22, Paige agreed to join the Portland Beavers. GM Bill Sayles had not signed a pitcher as much as he had a reputation, what today would be labeled a “brand.” Sayles announced that Paige’s first start would come on Aug. 27., at Sicks’ Stadium, against the Rainiers (how this boosted Portland’s attendance isn’t clear).

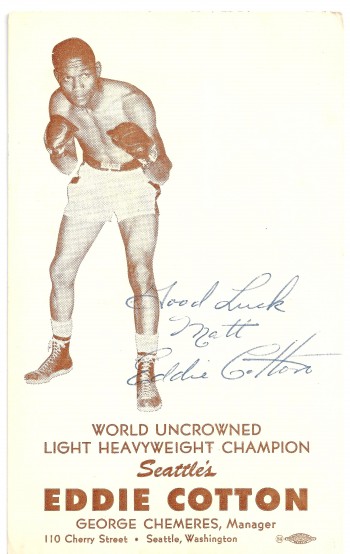

In any case, Seattle newspapers did not stop the presses for Paige’s appearance, maybe owing to a heavy news week: Seattle’s Eddie Cotton would challenge Philadelphia’s Harold Johnson for the world light-heavyweight title at Sicks’ two days after the Paige-Rainiers doubleheader; the Cincinnati Reds had just awarded Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson a two-year contract extension; ex-UW quarterback Bob Schloredt had that week been handed his first start in the Canadian Football League, for the British Columbia Lions against the Edmonton Eskimos. Seattle newspapers also spilled considerable ink on the APBA Gold Cup at Lake Pyramid, NV., speculating ad naseum over whether Bill Muncey could win again (he did). And the most popular attraction at Longacres, the colt Sparrow Castle, had a major stakes race on the same Sunday Paige would pitch.

Besides, and for all his fame, Paige hardly ranked as a Seattle novelty. He had made several excursions to the city in the mid-1930s, with the aforementioned House of David, pitching with that fake red beard. Years later, in September of 1946, the Satchel Paige All-Stars had faced the Bob Feller All-Stars, also at Sicks’ Stadium, as part of an interracial nationwide tour, which was Feller’s idea and significantly helped fuel the integration that occurred a year later when Jackie Robinson crossed the color barrier.

The Paige-Feller matchup at Sicks’ cost a dollar per ticket, proceeds earmarked to purchase recreational equipment for World War II vets convalescing at area hospitals. Paige and the 26-year-old Feller (wise beyond his years) took the mound with rosters of active-duty servicemen representing the Sand Point Naval Air Base and the Seattle Coast Guard Operating Base, supplemented by ex-major and minor leaguers. Paige worked five innings, the same distance Feller went, and yielded only one hit, that to Feller (a single). When the “world’s two greatest pitchers,” as Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Royal Brougham described them, departed the game, the score stood 2-1 in favor of Paige’s team (Paige ultimately received credit for a 3-1 win).

“It was Ol’ Satch who stole the show,” Brougham opined, “with a surprising assortment of stuff for a geezer going on 50 (a geezer himself, Royal miscalculated by a decade: Paige was actually going on 40)”.

“Seattle? Yeah, I’ve been here lots of times,” Paige told The Seattle Times after the Portland Beavers arrived in Seattle. “A good town. Real good. Used to play regularly here with the House of David. Yes, it was a long time ago. And then I was here with Bob Feller, and that was a long time ago.”

Talk about Paige’s mysterious age consumed all pre-game oxygen, and for good reason. It had already been 15 years since geezer Brougham called Paige “a geezer.” Dave Mann of the Rainiers insisted to the local rags that Paige was 65 years old. “It’s simple arithmetic. I played with him about five years ago,” said Mann. “Ol’ Satch was 60 then.”

For his part, Paige refused to be drawn into the debate “I’m between 50 and 60,” he maintained. “I’ll say no more than that”, but added, “I’ve got to pick my spots just a little now. I lean toward relief, actually. That way I can keep going for a long time. Your fastball loses a little snap when you cross 50.”

Due to that week’s news crush, or maybe because of Seattle manager Johnny Pesky’s tepid opponent, the Portland Beavers, the doubleheader drew 4,763, 2,888 fewer than witnessed Sparrow Castle rally from 10 lengths down in the stretch to win the Pacific Coast Maturity at the Renton oval.

Splitting the sympathies of a gallery that wanted to see Seattle win and Paige to perform well, the ancient worked four innings, then was lifted for a pinch hitter, Gerry Mason. Paige allowed two unearned runs in the first, three hits overall, walked two, fanned three and took a no-decision in a 3-2 loss, which followed an 11-8 Rainier win in the opener in which Seattle scoffed at an early four-run deficit by scoring seven runs in the seventh.

“The only thing we worried about was that he (Paige) might make us look bad with some trick pitch, like the eephus ball (very slow pitch that catches hitters off guard). Otherwise, he didn’t throw much different than anyone else,” said Rainiers outfielder Lou Clinton (well, the guy was 55 years old).

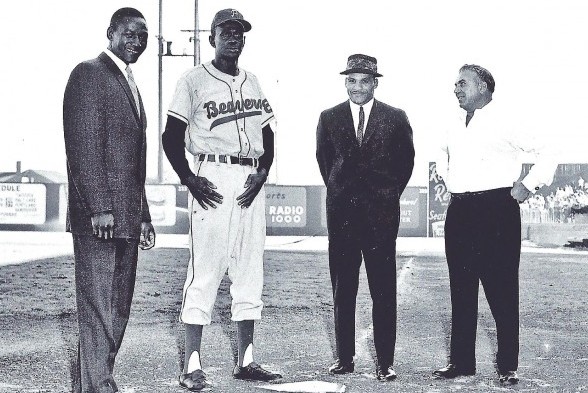

Among the 4,763 Sicks’ Stadium attendees on Aug. 27, 1961: Eddie Cotton, Harold Johnson and Johnson’s manager, Pat Olivieri (they are gathered, with Paige, at home plate in the photo above). Cotton had already lost one chance to become world lightweight champ and his Sicks’ Stadium bout likely would be his last shot. Sure enough, he dropped a split decision to Johnson, and it indeed marked his final title opportunity. Johnson, a Philadelphian, went into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993.

Olivieri (far right in the photo) is the second most-interesting man pictured. Years earlier, he had launched a south Philadelphia eatery, Pat’s King of Steaks, which became famous after Olivieri co-invented with brother Harry the Philly Cheesesteak, which, as one newspaper reported, “defines the town more than Tasty Kakes, soft pretzels and Champ Cherry Soda.”

Paige pitched just five games for the Beavers. In all, he went 0-0 with a 2.88 ERA, although the Beavers went 4-1 in his outings. His five appearances attracted crowds of 4,763, 4,437, 4,522, 3,613 and 4,574.

After his short stint in Portland, Paige returned to barnstorming. Finally, on Sept. 25, 1965, at age 59, Paige, in a set-up appearance designed to qualify him for a major league pension, pitched three shutout innings for the Kansas City Athletics, making him the oldest player to participate in a major league game.

Satchel Paige entered the Hall of Fame in 1971 and died of a heart attack in 1982. Most baseball historians now believe Paige pitched in more than 2,500 major league, minor league and barnstorming games (roughly 1,900 more than Cy Young’s major league total), winning some 2,000 (1,500 more than Young).

Since the results of his House of David games cannot not be fully documented, Paige finished with an unofficial record of 1-0 in Seattle, that 1946 decision at Sicks’ Stadium over Rapid Robert Feller.

—————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi, who writes “The Wayback Machine” every Tuesday. Check out David’s “Wayback Machine Archive”. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at the following e-mail address: seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

(“Wayback Machine” is published every Tuesday as part of Sportspress Northwest’s package of home-page features collectively titled, “The Rotation.”)

15 Comments

great article! thanks

Thank you so much for reading!

Nice article, well written! I always enjoy stories about the great characters of baseball and Ol’Dave is fast becoming another of those characters!!

We have more coming up. Thanks for visiting our web site!

Japan, man, I wish i was there. the atmosphere sounds incredible. awesome, even . . . keep us posted, Art!

Ichiro gets four hits but only 1 RBI. No matter where he hits despite the fact he’s the best hitter on the club it doesn’t help if no one’s on base.

Yosemite Sam …heh heh heh, that’s very descriptive.

As for Lynch … Oh goody, another pro player with the twins buttons of “I’m an Idiot” and “Self-destruct”.

multi-game suspension for an off-season DUI? — NFL is going way too boyscout– let the beasts play!

It could be very well that he was not intoxicated, might have a drink on his breath and that he was just a black man driving in Oakland. Just saying and I am white. And Thiel your the guy that also praises Lynch when he does well on the field. People make mistakes and stop being the Judge and Jury, DICK…

Lynch needs a wake up call. As Goodell once said, playing in the NFL is not a right but a privilege. Didn’t like letting Forestt go for the very reasons Art states here: he was one of the straight arrows of the team of whom I once had the pleasure of hearing him speak at a church. On a team where ability and accomplishments can sometimes overshadow transgressions the Hawks need to keep some of those types of personalities around to keep things in balance.

Robert Turbin better explode on the scene… or else the Hawks are a one-dimensional offense that just turned no-dimensional.

gosh, didn’t think about suspensions, it really is bad news! Getting the most out of undervalued, wayward players like Lynch is supposed to be Carroll’s strength….whaat happened?

There’s no history outside of Donte Stallworth that I’ve seen for players to be suspended for DUI, and his of course included a manslaughter. Raheem Brock had a DUI and a dine and dash incident and never was suspended and there wasn’t even discussion in the media of a potential suspension. Everything I read seems to be fait accompli that before charges, before a court date, before a potential trial (which would likely be in 2013), Lynch will be suspended at least 3 games, even though DUI history throughout the league indicates that even a single game suspension is rare. Reporters and commentators seem to have an agenda to push this belief while completely ignoring past precedent.

The facts will exonerate Marshawn. This is what really happened

Marshawn had spent the entire day in 90 degree heat with his church group putting a new roof on a homeless shelter which he had funded after his contract extension. And, as you can imagine, he and the rest of the flock had worked up a mighty thirst. So Marshawn dispatched his nephew, who had just turned 21 two days prior, to the local supermarket, giving him money to buy everyone lemonade. As the boy turned to leave, Marshawn told him to hurry, saying, “Hurry up, man! Go hard like I do!”

Misunderstanding the “Go hard!” reference, the youngster returned with several cases of Mike’s Hard Lemonade. Now, neither Marshawn nor the rest of the faithful laborers, being so entrenched in their Christian lifestyles, even knew what Mike’s Hard Lemonade was. But they did know one thing: it was ice cold and had a pretty yellow & black label with a lemon on it ! Now, I don’t know if you’ve ever had a Hard Lemonade on a 90 degree day, but I can tell you, it goes down pretty darned quick and you cannot taste the alcohol. .Marshawn proceeded to drink a case and a half by himself.

Believe it or not, this level of consumption barley even phased him. Remember, this is a man who eats a 1 lb. bag of Skittles just to warm up for practice. So, not surprisingly, he thought it was simply a combination of his usual sugar buzz and the sweltering heat that had tampered with his equilibrium. Nevertheless, there was still much work to be done on that roof. But, as Marshawn strapped his tool belt back on and hollered at his fellow parishioners to join him, he noticed that they had all passed out on the shelter’s front lawn.

Instead of quitting right then and there, Marshawn decided to do what he (long before Greg Jennings) had always done: put the team on his back. Marshawn worked into the night with only the street lights to guide his hammer, re-roofing that homeless shelter until 2:30 AM. He only stopped every ten minutes or so to hydrate himself with more of that delicious lemonade.

He then climbed down and loaded his still comatose Christians into the church van and proceeded to drive each of them safely home. After tucking the last one into bed at around 3:30, he finally staggered slowly back to the van and headed home himself. He was so exhausted he could barely keep his eyes open. And that’s when the flashing blue lights appeared in his rear view mirror.

So, you see, it was all just a big misunderstanding. The real tragedy here is that, some in Oakland =, there’s a homeless shelter with a really poorly built roof.

Saw this posted on the Field Gulls blog:

https://twitter.com/RossTuckerNFL/with_replies

Apparently a suspension for a substance abuse violation might void the guaranteed portion of Marshawn’s contract. If true, that may soften the blow to the Seahawks, and would ratchet up the pressure on Marshawn to earn his contract if he wants to continue getting paid.