By the afternoon of Aug. 26, 1932, not long after she alighted from a United Air Lines flight at Boeing Field, 200,000 people had gathered on both sides of Second Avenue in downtown Seattle, hoping to get a glimpse of one of the most famous women in America. As one news account described the largest ticker-tape parade in the citys history, “The scene resembled Armistice-signing outbursts in American cities when the World War (I) ended.”

The object of adoration rode in an open-top, flower-covered car, waving a bouquet of roses. Ahead of her, the Police Department Band marched and played, accompanied by a platoon of United States Marines. Mayor John F. Dore and Navy admiral Luke McNamee, who had just proclaimed the star of the proceedings Fleet Week Queen, followed in the motorcade.

Airplanes circled above as a snowstorm of multi-colored confetti filled the canyon of office buildings. Children scattered flowers in the path of the procession while cheers drowned out the sirens of motorcycle policemen as they tried to restrain the crowds that gorged the street.

Arriving at a newly constructed platform stationed at Metropolitan Square near the Olympic Hotel, Mayor Dore began his introduction.

“It is a pleasure to introduce a young woman who has done more in two years to give Seattle and the state the best kind of advertising than anyone who has ever lived here,” the mayor gushed. “The reception she receives today is greater than that received by anyone in the history of the city.”

And apt, considering that 19-year-old Helene Madison, a graduate of Lincoln High School, had pulled off a spectacular tour de force at the just-concluded Los Angeles Summer Olympic Games with a swimming performance that prompted sportswriters to variously dub her “Queen Helene,” ”The Invincible Mermaid,” and ”The Lindberg of the Waters.”

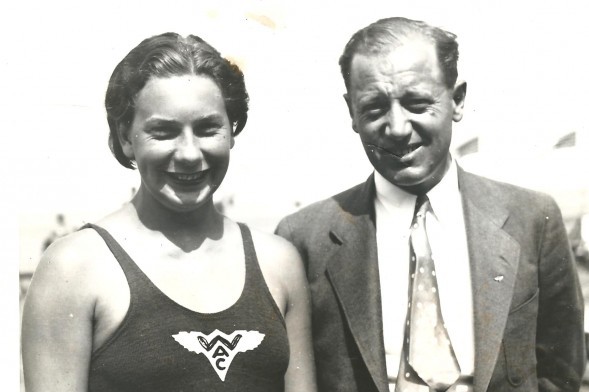

None among the 200,000 that day burst with more pride than Ray Daughters, who first spotted Madison as a gangly 14-year-old in the summer of 1927, taking part in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s annual Swim Carnival at Green Lake. Madison, who lived a block from the lake and had been participating in Seattle Parks Department swim programs since the age of six, had done nothing to distinguish herself from other girls her age, and was devoid of technique. But Daughters focused on her height – 5-foot-11 — big bones and the way she naturally navigated the water.

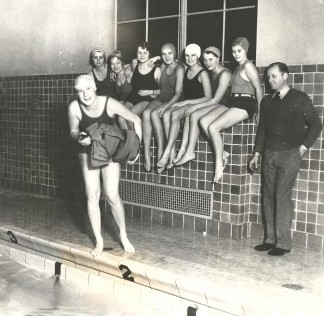

Daughters had a practiced eye. He had been a champion West Coast champion swimmer, setting a slew of freestyle records before becoming an instructor at Seattle’s Crystal Natatorium in 1924. Daughters figured that if he could teach Madison how to become more efficient in the water, refine her strokes and increase her strength, he might have a champion. So Daughters invited Madison to train under him at the Natatorium, a giant, multi-purpose bathhouse located on Second and Lenora in Seattle’s Belltown neighborhood.

Within weeks of joining Daughters, and after practicing two hours a day six days a week, Madison captured her first race of consequence, the Seattle Park Boards Beginner’s Swim at Green Lake. Nine months later, April 16, 1928, Madison set a state record in the 100-yard freestyle in 1:08.1, and also won 50-yard freestyle and 100-yard backstroke races at Crystal Natatorium.

Slightly more than a year later, (June 4, 1929), while competing for Crystal Natatorium in a dual meet against the Multnomah (OR.) Athletic Club, the 15-year-old Madison scored her first major breakthrough when she broke the Pacific Coast 100-yard freestyle record, set by Lily Bowman of Santa Monica, CA., two years earlier. Madison clocked 1:06.1 – only four seconds off Ethel Lackies (double gold medalist in the 1924 Olympic Games) world record established in 1926. Madison also won a 100-yard backstroke race.

When, through a series of regional swim competitions, Daughters discovered that no female in the Pacific Northwest could match his rapidly developing protégé, he arranged a match race to provide Madison with stronger competition. On April 28, 1929, at the Natatorium, Madison faced off in a 100-yard sprint against Albina Osipowich, a double gold medalist and the 100-meter freestyle champion at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympic Games.

Madison led by a yard halfway through the race, tired and lost by a forearm’s length. But the fact that Madison forced Osipowich to tie the world record of 1:10 in order to win convinced Daughters he had an emerging Olympian under his wing. She just required additional training, more strength and better competition.

Daughters entered Madison in the AAU Women’s Junior Swimming Championships in Detroit June 30, 1929. Competing against the best women her age (15), Madison routed the field over 100 meters. Later that year, Daughters placed Madison in a meet in Victoria, B.C. She set a Pacific Coast record at 200 yards, clocking 2:20.

In early January of 1930, using funds provided by Natatorium manager and financing angel Guy Sherwood, Daughters took Madison to Los Angeles, where, competing against Olympians, she set West Coast records at 100 and 220 yards. Those performances convinced Daughters that Madison was ready for the national spotlight, and she did not disappoint him.

At the Women’s National Swimming Championships in March of 1930, held at various Florida venues, Madison set her first world record, a 1:40.2 clocking in a 150-yard race at St. Augustine March 6. Two days later, Madison set a world record of 2:21.4 for 200 yards at Palm Beach. Five days later, she established more two world records, at 100 yards (1:00.4) and 220 yards (2:35).

Then, on March 18, Madison entered a 500-yard race in Miami. She not only won, she established world marks at 50 yards, 100 yards, 150 yards, 200 yards, 220 yards and 500 yards, timed in 6:16.2 overall. The record stood for 23 years. She concluded her first trip to the women’s nationals having captured every event from 100 to 500 yards while breaking eight world and American records.

When Madison returned to Seattle, Washington Athletic Club officials arranged a parade for her on Fourth Avenue and held a banquet in her honor at Civic Auditorium.

Madison had only warmed up. No one defeated her in 1930. No one came close to defeating her in 1931, the year the Associated Press named her its Female Athlete of the Year. Records tumbled in virtually every meet she entered, from distances ranging from 50 yards to a mile.

In the early summer of 1932, Madison traveled to New York City for the Olympic Swimming Trials at Jones Beach. She won the 100-meter freestyle and 400-meter freestyle, qualifying for the American women’s team.

By the time Madison arrived in Los Angeles to compete in the Olympic Games, no female swimmer had ever compiled a better career dossier. She owned 26 world records, had broken world and American records 117 times, and won every freestyle event at the U.S. Women’s Nationals in 1930, 1931 and 1932. During a 16-month stretch in 1930-31, she broke all 16 world freestyle records, and had become the first woman to swim the 100-yard freestyle in one minute flat.

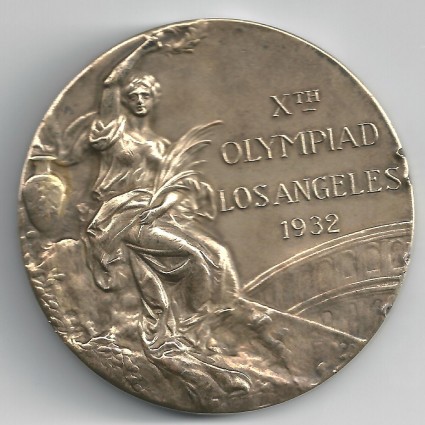

Two women achieved prominence at the 1932 Summer Games, track athlete Babe Didrickson and Madison. Didrickson set a world record in the 80-meter hurdles, an Olympic record in the javelin and tied the world record in the high jump. Madison set an Olympic record in the 100 freestyle (Aug. 6), a world mark in the 400 freestyle, (Aug. 11) and swam the anchor leg for the USA on the women’s 4×100 relay team (Aug. 12) that set a world record in 4:38.0. Madison won the 100 by a full second.

The first athlete from the state of Washington to win three gold medals in a single Olympics (still the only one), Madison celebrated her Olympic trifecta by agreeing to star in a Mack Sennett two-reel comedy opposite Johnny Weissmuller, dancing with Clark Gable at the Coconut Grove, and announcing that she would turn professional in order to cash in on her fame.

Madison had no money. The Natatorium, and later the Washington Athletic Club, had paid her expenses. Now she had to pay her own way, and she figured that becoming an actress and professional swimmer would suit her.

After the mayor introduced Madison, she told the throngs, ”I have entered my last race in amateur competition and will leave the field for good. My ambitions were realized when I scored in the Olympics. I have nothing else to look forward to. The grind has been a hard one, a tremendous task, and I am glad to give it over to other girls. My exact plans I am not at liberty to divulge, but I will return to Hollywood in a few days, at which time I will know more about my plans. Yes, it is possible that I will enter the cinema world, but until that is final I can say no more. But it is definite that I am through with swimming as a pastime.”

Two days after the parade (Aug. 28, 1932), Madison gave a swimming exhibition for pay at Bitter Lake Playland, a Seattle-area amusement park, and took possession of a new Buick, a gift from the Washington Athletic Club. Under U.S. Olympic Committee rules, Madison’s amateur career had come to an end, but Hollywood beckoned.

In those days, Tinsel Town fancied sports celebrities, and had since the late 1920s when Johnny Mack Brown, the star of Alabama’s 1926 Rose Bowl victory over Washington, launched a long career as a movie cowboy. Weissmuller, the swimming star of the 1924-28 Olympics in Paris and Amsterdam, came next, starring in Tarzan The Ape Man, released in 1932. Three years later, Edgar Rice Burroughs recruited Herman Brix, a former University of Washington football player and another 1928 Olympian, to appear in The New Adventures of Tarzan. Ex-Notre Dame fullback Joe Savoldi, boxer Georges Carpentier and USC football players Orv Mohler and John Wayne also entered the movie business. Buster Crabbe, the male swimming star of the 1932 Olympics (gold, 400 meters) started working in Hollywood about the same time Madison did, had a long career in oaters and starred in Flash Gordon serials. Paul Schwegler, another former UW football and track star, had been given a screen test and would go on to appear in Bright Eyes, starring Shirley Temple.

On Nov. 14, 1932, Madison signed with Sennett to appear in a comedy titled Help, Help Helene. The movie never got made, or at least was never released, but Madison did star in the Sennett-produced The Human Fish (1932). It bombed at the box office. So did two subsequent movies, The Warriors Husband (1933), in which Madison made a cameo appearance, and Sports Slants (1934), in which Madison played herself. That ended her movie career.

Madison took a trip to Auga Caliente, Mex., with her Olympic swimming teammates to participate in an exhibition, then got another gig at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair without finding any basis for a paying career. The Depression had wiped out any potential market for exhibition swimming, so Madison returned to Seattle.

“I never made a nickel out of turning professional,” Madison rued later.

Madison attempted to become a nightclub entertainer, but did not have the personality for it. Said Olympic swim teammate Jane Manske (wife of football player Eggs Manske, the last NFL player to play without a helmet) in an interview years later: “Helene was an interesting individual due to the fact she was so much of a loner. She spent most of the time by herself painting her fingernails and toenails bright red.”

Madison applied to become a Seattle swimming instructor, but the Parks Board rejected her, Madison explaining later, ”They wouldn’t accept a woman for the job. She also clerked at a department store.

One year following the 200,000-person salute she received on Second Avenue, Madison had disappeared from public view as the Seattle media attached itself to a new swimming sensation, Jack Medica of the University of Washington, also coached by Daughters. Medica, the UWs greatest swimmer, won NCAA championships in the 220, 440 and 1,500 freestyle races three years in a row (1934-36), and captured the 400 freestyle gold and two silver medals (1,500, 4×200 relay) at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

While Medica won medals in Berlin, Madison sold hot dogs out of a beach kiosk at Green Lake to raise the tuition she needed for nurses training at Virginia Mason Hospital. But she never became a registered nurse, the greatest disappointment of her life.

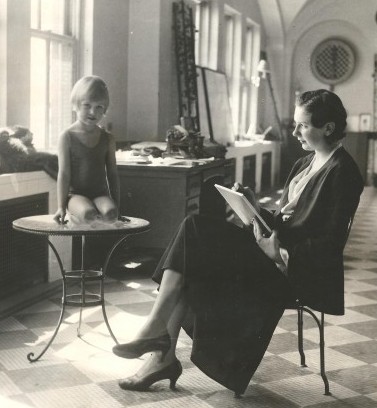

In the late 1940s, Madison opened a swimming school at the Moore Hotel Pool, adjacent to the Moore Theater, which she operated for 13 years. Future Olympian Nancy Ramey, then a pre-teen, became her prize pupil. In 1956, Ramey won a silver medal in the 100 butterfly at the Melbourne Olympics. Two years later, she set world butterfly records at 100 and 200 meters.

Madison had no luck in her personal life. She married and divorced twice. In 1952, she had major back (spinal) surgery, and then suffered two minor strokes. Deteriorating health forced her to close her swimming school in 1958. In 1965, Madison learned that she had diabetes. Her various incapacities kept her from offering swimming lessons and working part time in a convalescent home, her sources of income. What little money she had saved began to dry up.

Madison, named to the new Washington State Sports Hall of Fame in 1960, learned in 1966 that she had been selected for induction into the International Swimming Hall of Famein Fort Lauderdale, FL. When reporters called her about her selection, she said, I don’t have any way of getting there. I can’t afford to pay for the trip myself.”

The Washington Athletic Club picked up the tab.

A year later (1967), and to Madison’s great anguish, Daughters died at age 72, his legacy extending well beyond the careers of Madison and Medica. Swimmers coached by Daughters set 30 world records, 301 American records and won 64 national championships.

In 1969, Madison learned she had throat cancer, which required Virginia Mason doctors to replace her esophagus with a piece of intestine. “This is about as big a surgery as anyone can have,” said a Virginia Mason spokesperson.

The ensuing cobalt treatments forced Madison to miss more work. Slowly, she went broke. When her financial plight became public, The Seattle Post-Intelligencer conducted a fundraiser for her and the Licensed Practical Nurses Association held a benefit dance in her behalf, charging $5 admission.

Madison spent her final months living alone in a basement apartment at 6612 Sunnyside Ave. N., within site of Green Lake. Her once-blonde hair had turned gray and her only company was a parakeet named Jimmy and a Siamese cat named Punky. When she could, she walked the streets around Green Lake, unrecognized. She enjoyed sitting by her window watching Little League baseball across the street, drawing (a life-long hobby), and listening to University of Washington football broadcasts on the radio.

In one of her final interviews, she told an Associated Press reporter, “Sonny Sixkiller. Isn’t that a beautiful name?”

As for her swimming career, she said, ”Only once did I lose. They put me in a backstroke race against Eleanor Holm (an Olympic teammate) and I splashed half the water out of the pool and swallowed the rest. But I placed third.”

Asked if she regretted retiring at age 19, she said, ”I don’t think I had peaked yet when I retired. But it was the Depression. I had to work.” And she added, ”Then, as now, I was broke.”

Madison kept her three Olympic gold medals on a fireplace mantle. They had turned black because she no longer had the strength to keep them polished. Among her other prizes: three shell casings from the guns used to start her Olympic medal races.

Madison’s three-year career remains one of the shortest in swimming history, but no one else ever retired with every available goal achieved — all available Olympic freestyle events, all available National Championship events three years in a row, and 16 official World freestyle records in 1932.

Madison’s U.S. 500-yard freestyle record lasted 23 years, her 100-meter freestyle mark 15 years, her 220-yard freestyle record six years, and her 880 freestyle mark five years. No one, before or after her, ever held every freestyle record simultaneously.

In 1992, Madison became the first athlete from the state of Washington to enter the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame. Two swimming pools bear her name, one near Ingraham High at 13401 Meridian Avenue N., the other at the Washington Athletic Club. She didn’t live to see either dedicated.

Helene Madison died in her basement apartment at age 57 Nov. 25, 1970, and was cremated without any service.

———————————————–

Many of the historic on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports ?aficionado David Eskenazi, who writes The Wayback Machine every Tuesday. Check out DavidsWayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at the following e-mail address: seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

(Wayback Machine is published every Tuesday as part of Sportspress Northwests package of home-page features collectively titled, The Rotation.)

————————————————

Note To Readers: If you have an historical topic you would like explored in the Wayback Machine, please leave your idea in the Comments section that accompanies this article.

3 Comments

Once again, a VERY complete account. It almost is like you write a New Yorker type-article every week. That must be tough.

Actually, it’s fun to explore the history of sports in this area. And we thank you for visiting our web site and reading.

Wonderful, engaging article – I had never heard of Helene Madison before now, and loved reading about her life (even if it did turn sad). Columns like this and Paul Dorpat’s “Now and Then” have made me nostalgic for a Seattle I’ll never know.