By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

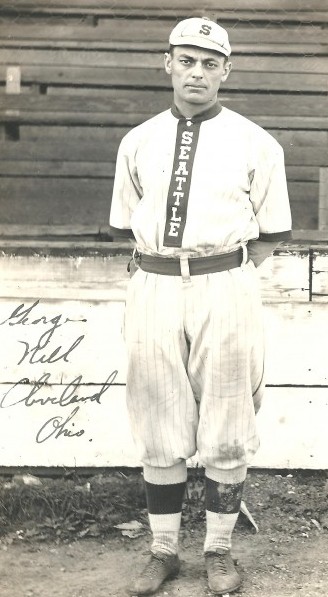

On April 16, 1912, one day after the unsinkable Titanic sank to the bottom of the Atlantic, 20-year old pitching prodigy Bill James made his professional debut with the Seattle Giants, the city’s entry in the Class B Northwestern League.

Relying on an exceptional fastball, plus a spitball that mesmerized 6,000 fans assembled at Yesler Way Park (12th Avenue and Yesler), James worked five innings against the Portland Colts, allowing three earned runs on seven hits with two walks and four strikeouts. Not a bad outing, but it could have been far worse.

James was so anxious to get off right that he kept “putting too much stuff on the ball,” the Seattle Times reported in the next days edition.

“The result was his control was a bit uncertain, and he was in the hole a great part of the time. The kid looks good, though, and he will pitch some good ball for Seattle this year.”

The 6-4, 10-inning loss to Portland that day – James received a no-decision and reliever Bill Barencamp took the loss — dispatched the Giants to last place in the league standings, where they remained mired until the end of May, by which point most every baseball fan in Seattle had abandoned hopes of owner Dan Dugdale’s club contending for the league title.

But the resourceful Dugdale, who had signed James to his first professional contract, made a series of moves with the aim of extricating his team from its two-month malaise.

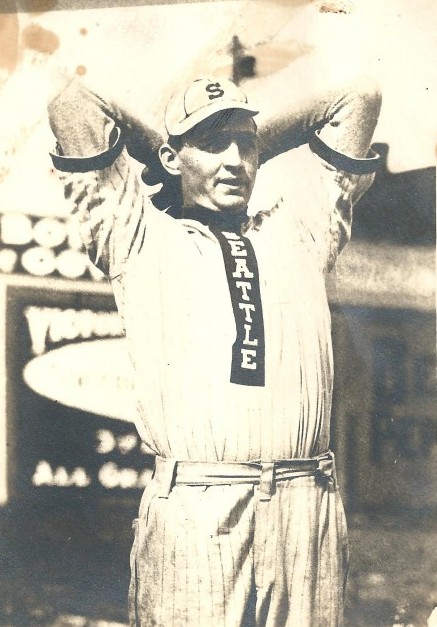

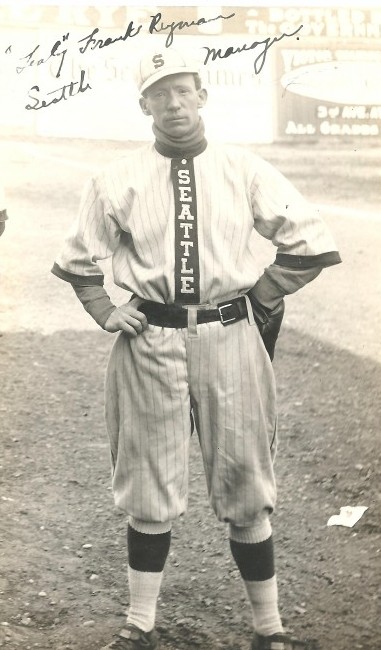

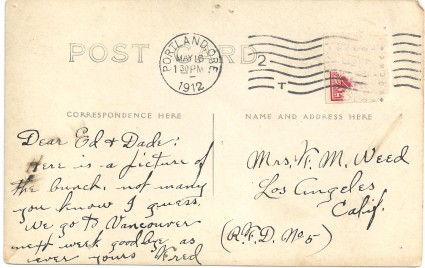

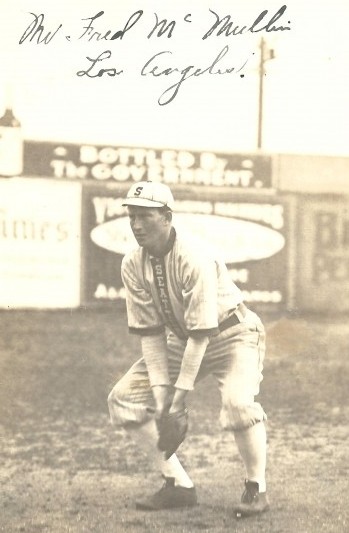

Deciding the Giants needed more experience in the infield, Dugdale sold 20-year-old infielder Fred McMullin, whom he considered too green to be of much help to the club, to the Tacoma Tigers. Then, after the Giants lost both ends of a doubleheader May 30 at Spokane, Dugdale fired manager Shad Barry, a 10-year major league veteran with whom he had frequently squabbled, and replaced him with Frank Tealy Raymond, who became player-manager and largely took over McMullin’s role in the infield (McMullin played all positions except first base).

Less than a month later, with James emerging as a hot prospect, the pitching-poor Boston Braves of the National League proposed to pay Dugdale $7,500 for James and catcher Bert Whaling, the most ever offered by a Major League team for a minor league battery. As part of the transaction, the Braves insisted that James and Whaling report to Boston ASAP.

Always lauded as a shrewd businessman (he had made his money speculating in real estate), and often accused of running his ball clubs on the cheap, Dugdale refused, saying he would never part with a player at midseason — even for $10,000.

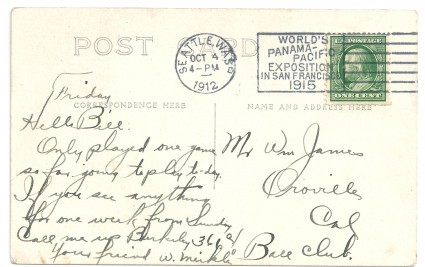

But on June 24, 1912, with the Giants in Portland to play the Colts, Dugdale confirmed to sports writers that he had agreed to sell James and Whaling to the Braves. The key change from Boston’s first offer: the Giants would retain the services of James and Whaling throughout the 1912 season, and the pair would report to the Braves in 1913.

Dugdale would not publicly disclose the price Boston would pay, but later revealed the figure to members of the James family.

“The price was $9,000,” said James daughter Janet Holden, who lives in Stockton, CA. “Dugdale said that $8,999 of it was for my father and $1 dollar was for the catcher.”

Dugdale had no option other than to sell his blossoming star. Under rules of the day, if a major league team and a minor league club could not come to an agreement on the sale price for a player, the major league team could draft the player (end of season) and only owe the minor league team $750. This made it virtually impossible for a minor league club to keep a promising prospect for any length of time.

That James would not report to the Braves until 1913 became the most important factor in one of the more improbable pennant races in Pacific Northwest baseball history — one, in fact, that bears a striking similarity to another that occurred 83 years later, in the summer of 1995.

That year, on Aug. 2, the Mariners found themselves 13 games out of first place in the AL West after a 5-4 loss to California, their postseason hopes seemingly dashed. Three weeks later, on Aug. 23, the Mariners still stood 11.5 games back after the Orioles torched Bob Wolcott 7-1.

Even after Ken Griffey Jr., having just returned from a 73-game absence (broken wrist), walloped a two-run, walk-off homer off John Wetteland of the Yankees a day later (Aug. 24), giving Seattle a 9-7 victory, a postseason appearance seemed hopelessly far-fetched.

But as events developed, Griffey’s poke into the right field seats at the Kingdome off the New York closer turned out to be no ordinary salami, serving instead as the launching point for six of the most exciting weeks in Seattle sports history.

Nearly every Mariner game during that span — or so it seemed — involved a theatrical, come-from-behind rally. All games riveted every fan the team had, and created so many new ones that those six weeks literally saved the franchise from relocation.

“The whole town suddenly awoke to the fact that one of the great races in the history of baseball was being staged here . . . Prominent business and professional men neglected their affairs to attend to every game, and the Seattle team was supported right down to the last minute of every game.”

That Seattle Times summation offers an accurate snapshot into the Mariners 1995 playoff run. But the Times published those words in 1912, not in 1995, to describe the gripping effect the Giants had on the city.

While the 1995 AL West race evolved into a question of how many times the Mariners could mount stunning comebacks, and simultaneously how far and fast the Angels could fall, the 1912 pennant race included all six of the Northwestern League franchises – the Giants, Portland Colts, Vancouver Champions, Tacoma Tigers, Victoria Bees and Spokane Indians.

At one point or another, each team occupied first place, and each spent time in last place.

In 1995, the Mariners had to win 24 of their final 35 games (.686), including 19 in September, to forge a final-day division tie and force a one-game playoff with the Angels at the Kingdome, played there only by dint of a coin flip that, luckily, fell Seattle’s way.

In order to finish first in 1912, the Giants had to win 27 of their final 31 (.871), many of the games also involving enthralling comebacks.

The 1995 Mariners seemed to generate an unlikely hero daily, including non-starter Alex Diaz, a season-long .248 hitter who belted a three-run, pinch homer in the bottom of the eighth inning Sept. 22 off ex-Mariner Rick Honeycutt to rally the Mariners to a 10-7 win over the Athletics that finally put Seattle a game up on the Angels.

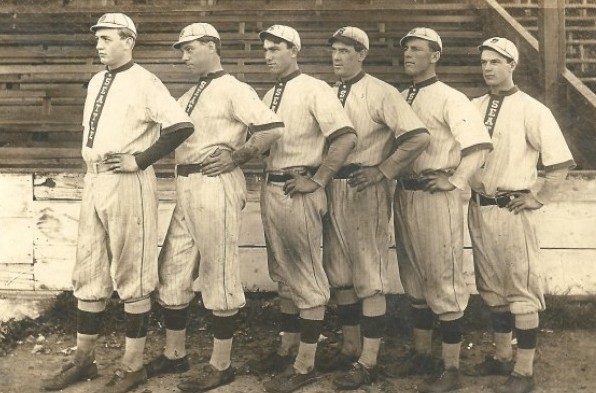

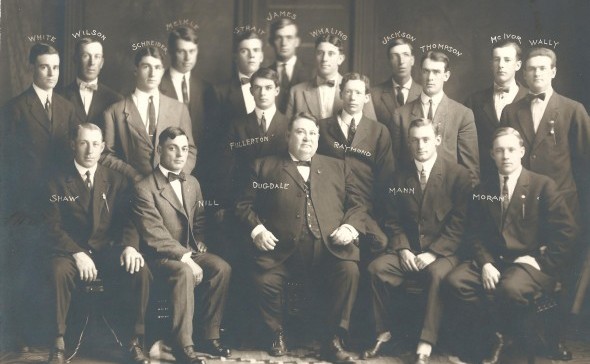

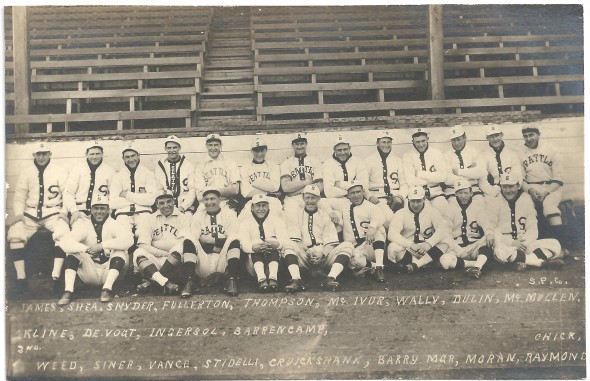

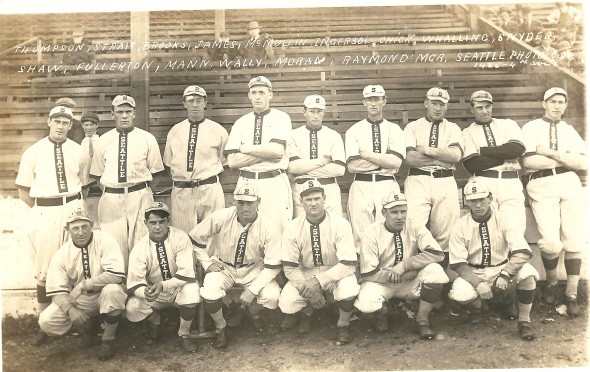

The 1912 Giants had a similar step-up crew, especially in 23-game winners Charles Fullerton and Cecil Thompson, infielder Hunky Shaw (.281 BA) and outfielders Les Mann (.300 BA, 23 home runs) and Lee Strait (.298).

Just as two late-season imports, Vince Coleman (hit .290 over Seattle’s final 40 games) and Andy Benes (7-2 in 12 starts after the Mariners acquired him from San Diego) boosted the 1995 Mariners, a trade by Dugdale in August, 1912, substantially bolstered the Giants.

But while his swap of pitcher Jimmy Concannon and infielder Fred Chick to Tacoma for infielder-outfielder George Rabbit Nill and Will Meikle (0.31 ERA in seven appearances, including two starts) became an important component in the Giants pennant run, Bill James, the spitballer, ultimately made the biggest difference.

“The Big Fellow (James) is as strong as horseradish when he really has to pitch,” the Seattle Times wrote July 12, 1912.

Born March 12, 1892, in Iowa Hill, CA., a gold mining town 30 miles northeast of Sacramento, James grew up mostly in Oroville (Oro: Spanish for gold; Ville: French for town), 50 miles north of Iowa Hill. According to the National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, James attended Oroville Union High School, where he starred in baseball and basketball.

By his senior year, the 6-3, 195-pound prodigy had developed a fastball with big league movement and an effective change of pace pitch (changeup first coined in 1948, according to The Dickson Baseball Dictionary).

“When he was in high school, he played baseball, basketball, golf, tennis, everything,” said daughter Janet. “He kept getting letters from all these clubs from up and down the West Coast inviting him to come and join their baseball teams.

“My grandfather had owned a gold mine and became an engineer in Oroville (after the mine petered out). He told my dad that he was not to become a baseball player. He wanted my dad to become an mining engineer.”

Reluctantly, James attended classes at St. Mary’s College in Oakland, but the offers to pitch continued.

James’ father grudgingly acquiesced to his son’s wishes after taking a liking to one of the offerees, Dugdale, whose Giants had won the Northwestern League pennant two years earlier playing as the Seattle Turks.

“As my father left for Seattle,” Janet Holden said, “my grandfather gave him $50. My grandfather told him, ‘This is to bring you home because you are never going to make it.'”

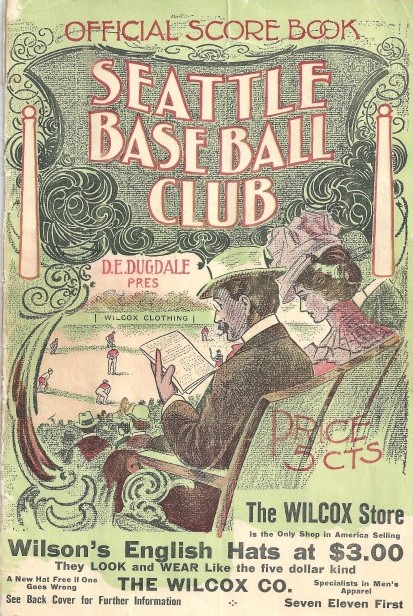

In those days, the Giants, as well as the Turks (1909) and Siwashes (1907-08) before them, played at Dugdale-owned Yesler Way Park, a facility Dugdale erected in 1907 at a cost of $10,000.

Yesler Way Park accommodated 3,000 fans in the main grandstand and 1,500 each in the right and left field bleachers.

Like the 1995 Mariners, who didn’t create a fan frenzy at the Kingdome until their September run, the Giants did not attract significant crowds to Yesler Way Park after falling into last place, nor did they rouse the citizenry much even after Tealy Raymond got them out of the cellar and back in the pennant race.

But in the last month of the season, the suddenly surging Giants drew throngs to the park and received front-page coverage in Seattle’s newspapers, rivaling the ink devoted to ex-President (1901-09) Teddy Roosevelt’s series of stump speeches on behalf of local Bull Moose Party candidates on Second Avenue in mid-summer.

“The winning of the pennant in the last three weeks of the season after Seattle seemed destined to run a poor third to Spokane and Vancouver created more baseball enthusiasm in this town than has been evidenced here for 10 years,” the Times reported, referring to the 1902 Pacific Northwest League pennant race between Dugdale’s Seattle Clamdiggers and the Butte Miners (won by Butte).

“Spokane seemed ready to displace Seattle in first place right up to the next-to-last day of the season,” the Times continued. “The race all year was a remarkable one, for at one time the six clubs were so closely bunched that the winning or losing of a couple of games would send the leaders bouncing to the bottom and shoot the tail enders to the top.

”Until the last month, the season had been a failure, the fans only lukewarm. Few thought Seattle had a real chance for the flag. But after (Rabbit) Nill and (Willard) Meikle were brought here, the team hit its stride. The team mowed down opponents, and fans flocked to the park.”

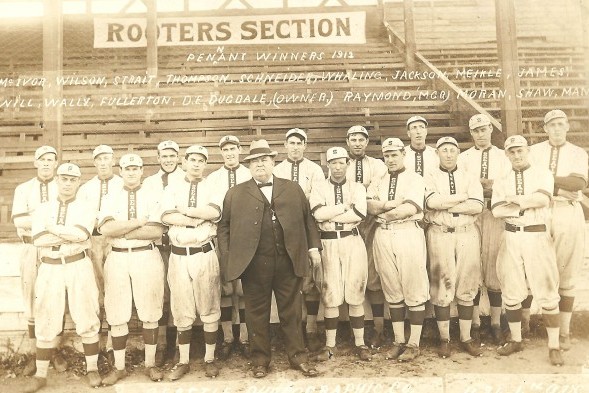

The Giants became so popular that they inspired the formation of The Rooters Club, a clique of diehards that bonded together at the urging of Seattle newspapers, and apparently the first formal booster group to support a Seattle pro sports franchise.

”The Rooters Club simply inspired the team and it swept on to victory,” wrote the Times. ”Take young Leslie Mann, for instance. This is only his second year in baseball, and in the middle of the season he slumped badly and his whole play was affected.

“But once the homestretch was reached and the park every day was filled by wildly enthusiastic men and women, young Mann came back with his own rush. For the last three weeks the young fellow has been to the Seattle team what Ty Cobb was to the Detroit club in its pennant-winning days.

“It was simply impossible to stop Seattle in the last three weeks,” the Times continued. “They took six out of eight games from Victoria, the team that did the most to land Seattle in the cellar in the opening weeks of the season. They made a clean sweep of seven games with Portland, and they beat Tacoma to win the pennant (the Giants finished 99-66 to Spokane’s 95-72 and Vancouver’s 94-73).”

Local newspapers made much of the season’s final series against the Tigers, since their manager, Mike Lynch, had skippered the Seattle Turks when they won the 1909 Northwestern League title, and had also managed the 1910-11 Seattle Giants before bolting to Tacoma after a dispute with Dugdale (in Thorn and Holway’s The Pitcher, Lynch is credited with possibly inventing the forkball) that may have been exaggerated by reporters in the interests of hyping the series.

Another similarity between the 1995 Mariners and 1912 Giants: both teams had ballpark-related issues.

The Mariners had argued for years that the Kingdome had devolved into an inadequate facility and that, without a new ballpark, they would be forced to relocate. Their late-season, division-clinching spree created just enough momentum for the state legislature to sign off on a funding package, over the objections of many.

In 1912, numerous Seattle developers hounded Dugdale to sell his much-coveted Yesler Way Park property. Dugdale resisted all offers until his club’s late-season pennant run helped convince him that he needed a more expansive facility (the Giants moved into 10,000-seat Dugdale Field in 1913, the first double-deck ballpark on the West Coast) and it served as Seattle’s principal baseball park until 1932, when an arsonist torched it.

Thus, the last-month performances of both the 1912 Giants and 1995 Mariners ultimately resulted in the construction of new Seattle ballparks.

Ten members of the 1912 Giants either had spent, or would spend, time in Major League Baseball, including Yakima native Hunky Shaw, the 1910 Pacific Coast League batting champion (.281 with the San Francisco Seals) who came close in 1908 to becoming the first major leaguer born in the state of Washington.

A former University of Washington star, Shaw landed with the Honus Wagner-led Pittsburgh Pirates (May 16) a week after Vancouver catcher Jack Bliss made his debut (May 10) with the St. Louis Cardinals (after Shaw’s career ended, he owned and operated Yakima’s franchise in the Western International League and also owned a Yakima funeral home).

Mann, who hit a Northwestern League-leading 23 home runs for the 1912 Giants, spent 16 years with the Braves, Cubs, Cardinals, Giants and Whalers (Federal League), batting .300 or better six times and .282 overall in 1,498 games. Along the way, Mann played with Hall of Famers Mordecai Brown (Cubs), Rogers Hornsby (Cardinals and future manager of the Seattle Rainiers), Casey Stengel (Braves) and Bill Terry (Giants).

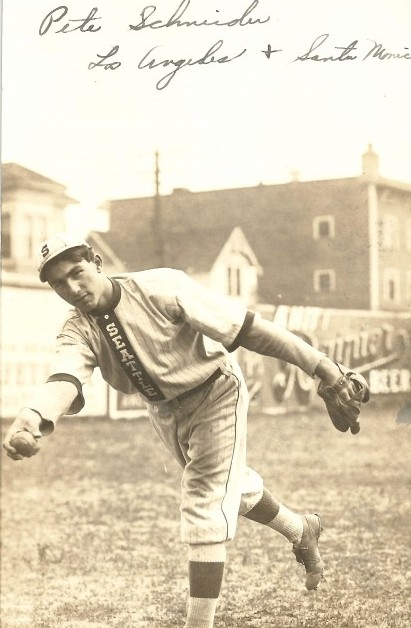

Pete Schneider, who went 7-8 for the 1912 Giants, won 20 games for the 1917 Reds and also pitched for the Yankees. Following his Major League career, Schneider played in the Pacific Coast League. Converted to an outfielder, and playing for the Vernon Tigers, he set single-game league records May 11, 1923, by hitting five home runs with 14 RBIs during a 35-11 romp over Salt Lake City. Schneider missed a sixth home run by two feet when he belted a line-drive double off the center field fence.

Rabbit Nill, who hit .272 for the Giants, spent five years with the Washington Senators (played with Walter Johnson) and Cleveland Naps (played with Nap Lajoie) before signing with Seattle.

Infielder Fred McMullin, sold by Dugdale to Tacoma after the Giants fell into last place, hit .256 in a six-year career with the Chicago White Sox. McMullin would have become a forgotten man had he not become the Eighth Man Out in baseball’ s 1919 Black Sox Scandal, in which the White Sox threw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds.

Indicted by a Chicago grand jury and suspended from baseball permanently for accepting a $5,000 bribe to help his team lose, McMullin couldn’t even play in semi-pro games after his banishment. Ironically, as SABR has reported, McMullin once chased gamblers off a field in Boston, and he spent the final decade of his life – he died in Los Angeles in 1952 at the age of 61 – as a law enforcement officer.

Despite McMullin’s historic infamy, James presents the most intriguing story line of any member of the 1912 Seattle Giants.

In the second half that year, James won 16 consecutive games and would have made 17 if he hadn’t taken a no-decision on Aug. 15 against the Vancouver Champions when he toiled 11 innings and fanned 12. A more typical James outing occurred Aug. 29, when he blanked Tacoma 11-0 on four hits with six strikeouts.

James finished with a league-leading 26 victories against eight losses. No Seattle pitcher topped 26 victories until “Kewpie” Dick Barrett won 27 for the Seattle Rainiers in 1942 (Barrett named Minor League Player of the Year by The Sporting News, the highest accolade available to a minor leaguer). James’ 2.17 ERA also led the league, as did his winning percentage (.765) and strikeout total (201).

”It may be years before Seattle will get another pitcher like Bill James,” wrote the Seattle Times.

Twenty-six years, to be precise — when 19-year-old Franklin High graduate Fred Hutchinson of the 1938 Rainiers went 25-7 with a 2.48 ERA.

Fielder Jones, who managed the 1906 Chicago White Sox, aka The Hitless Wonders, (won the 1906 World Series despite a .230 team batting average) and later ran Oregon States baseball program, served as Northwestern League president in 1912. After the Giants won the pennant, Jones said, ”Bill James possesses a good spitball. I think he has the makings of a star.”

When James made the move to Boston in 1913 (not only did Whaling go with him, as per their June 24, 1912 sale, so did outfielder Les Mann), the first thing he did was remind his father that he had, in fact, “made it.”

“After the sale, he sent the $50 back to his father,” said daughter Janet.

James left town as the first in what would become a long line of one-year wonders to play for Seattle athletic teams. But he has a more unusual distinction: James might be the only one-year wonder to become a one-year wonder twice, first with the 1912 Giants, again with the 1914 Boston Braves.

Christened Seattle Bill James, a nickname given him to avoid confusion with Big Bill James and William Lefty James, both of the Cleveland Naps, Seattle Bill posted a 6-10 record with a 2.79 ERA as a Major League rookie in 1913, then came back in 1914 with a season worthy of Walter Johnson and Christy Mathewson.

James went 26-7 (National League-best winning percentage of .788) with a 1.90 ERA in 37 starts. He worked a remarkable 332.1 innings, threw 30 complete games with four shutouts and added three saves as the Braves, stuck in last place July 4, became the first team in history to surge to the pennant after such a horrid start.

James led the National League in WAR (wins above replacement) at 7.7, had more wins than Mathewson (24) and a better ERA than Grover Cleveland Alexander (2.38).

The Braves’ stunning reversal of fortune long ago entered baseball lore as the most unlikely championship run in history, but the role James played in the miracle uprising largely fell into obscurity, mainly because James did.

That shouldn’t have happened. From July 9 until the end of the season, James posted a 19-1 record with a 1.51 ERA. His only defeat occurred Aug. 22 in Pittsburgh, when he lost 3-2 in 12 innings. Without that setback, James would have compiled a record-breaking 20-game winning streak.

Gamblers installed Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics, the defending champions, as a heavy favorite to win the World Series, but the Miracle Braves were more than up to the challenge, in large part because of James. In Game 2 at Philadelphias Shibe Park, James threw a complete-game, two-hit, 1-0 shutout with eight strikeouts, outdueling future Hall of Famer Eddie Plank. He also induced a game-ending double play with the tying and winning runs on base (leading off for Boston, ex-Giant Les Mann went 2-for-5 with an RBI).

Working in relief of Lefty Tyler in Game 3 two days later at new Fenway Park, James pitched two scoreless innings without allowing a hit and collected his second victory of the Series. Boston capped off its sweep, the first in World Series history, with a 3-1 victory in Game 4.

With that performance, Seattle Bill James stood on the cusp of fame, a Matthewson-Johnson-Alexander-Plank in the making. But the 23-year-old flamed out less than nine months following his World Series victories.

After reporting late to the Braves in 1915 (he held out in a contract dispute, demanding $6,000 while the Braves offered $4,000), he complained of arm fatigue, lost his velocity, and eventually his spot in Boston’s rotation. At mid-year, the Braves sent James to the bullpen, but after a poor relief effort in late July, they shelved him for the year, placing him on the retired list. James had a 5-4 record, a 3.03 ERA, and he never won another game at the Major League level.

Rabbit Maranville, one of two future Hall of Famers on the Braves’ roster (also Johnny Evers, his Tinkers-to-Evers-to-Chance days long gone), told Boston newspapers, “We know Bill’s arm is gone. So does he.”

Boston and New York reporters described James as suffering from a dead arm. But many researchers, including some from the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR), now suspect that James ailed from a torn rotator cuff that went undiagnosed because such a condition was unknown to the doctors of his day (even if diagnosed, it could not have been treated). Daughter Janet Holden recalls looking at her father’s arm and wondering what was wrong with it.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if that was it (rotator cuff),” Janet said. “He went to a place in San Francisco to try to get it fixed. But he never could do much with his arm. I don’t think he ever knew for sure what was wrong, at least not to my knowledge.”

James spent 1916 serving in the U.S. military (63rd Infantry) during World War I. Following several operations (none successful), he attempted a comeback with the Braves in 1919, but drew his release after just one 5.1-inning relief appearance.

James pitched for five teams in the Pacific Coast League, Southern Association and American Association between 1917-25, including one 3.0-inning relief outing for the 1920 Seattle Rainiers. But he never again produced a winning season, going 33-50 in his post-MLB minor league career.

With James, Mann and Whaling gone to Boston in 1913, the Giants slipped back to third place. Still managed by Tealy Raymond, they finished second in 1914 and won another pennant in 1915. (Raymond was involved in West Coast and Northwest baseball as a player and player-manager for many years (1903-17), and ended up as a manager only in the 1920s in Yakima and Bellingham, where he managed “Tealy’s Tulips.” He also owned a bar there with another ballplayer, Elmer Bray.

The Giants began their fade into history in 1917, when Seattle Bill James launched one of his numerous and unsuccessful comebacks. The two-time, one-year wonder returned to Oroville following his career, and worked as a truck driver and for the Butte County assessor. He also kept his hand in baseball, managing the semi-pro Oroville Olives and Chico Colts for more than a decade.

Born in 1926, daughter Janet recalls a frequent visitor to the James home, baseball legend Ty Cobb, the game’s greatest hitter and a notorious woman chaser.

“Knowing my father lived in the area, he just came to our house one day,” said Janet. “Ty Cobb came to the house a lot. He had a lot of girlfriends all over California (and used the James home as a base of operations). My mother didn’t like him (Harriet James considered Cobb a bad influence). When he came to the house, she wasn’t very thrilled. My dad wasn’t really a friend of his. He felt that Cobb didn’t always tell the truth. But for some reason, he wanted my father to think well of him.”

“Seattle” Bill James died of a stroke March 19, 1971, at the age of 78, one month after moving into an assisted-care facility. Seattle newspapers only briefly mentioned his passing (two-inch obit).

“He was just a gentleman,” said Janet, who wrote a booklet about her father titled From A Small Town Boy To A World Series Champion. “He knew everybody in Oroville, and I don’t think I ever met anybody who didn’t like him.

“When I was a little kid during the Depression we always had people coming to the house asking for work. My dad always gave them an extra dollar even if they just swept the front porch. He had my mother make some Van Camp’s pork and beans with bread and butter and beer, and they would all have their lunch. He was probably one of the nicest fellas you could ever meet.”

Bill James’ Records With The 1912 Giants and 1914 Braves

| Year | Team | Games | Won | Lost | Pct. | ERA | K’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912 | Seattle Giants | 42 | 26 | 8 | .765 | 2.17 | 201 |

| 1914 | Boston Braves | 46 | 26 | 7 | .788 | 1.90 | 156 |

Check out David Eskenazi’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

6 Comments

I was surprised that Clement didn’t work out. I’ve always wondered if the M’s simply screwed up in handling his progress because he was like Aaron Curry for the Seahawks: a can’t miss prospect with All-Pro written all over him. The fact that he didn’t make it in Pittsburgh shows at least they were able to trade him but that just netted them Jack Wilson. Can’t remember the last decent catcher the club has drafted.

Oh, wait. That guy who was traded to Boston. With a pitcher. For a closer. Yeah.

look for adam moore to be the hot-hitting catcher for the kc royals in 2013.

it would have been like a good baseball move for the mariners to have acquired kevin youkilis and $5m in cash and put youk at 1st base in lieu of justin smoak but no fire. and we couldn’t have that in seattle, could we?

in 11 games with chisox, youk is

.310

.370

.476

Don’t forget the thick layer of marine air!

Oh yeah, can’t forget that. I wonder how all the other teams on the West Coast and all the teams on the East Coast get past that? Especially in Florida?