By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Thirty-one years ago, when no instant Internet gratification existed, George Brett of the Kansas City Royals confided to a Sports Illustrated reporter that he made a habit of checking out the sports section of his local newspaper (Kansas City Star) every Sunday to find out where he stood in relation to other American League batters.

Today, Brett could sort his batting prowess against right handers and left handers, monitor his performance on grass and turf, view it through the prism of day and night games, observe what he did on any pitch count, and study it by ball park and days of the week. But in the absence of batting splits 31 years ago, Brett had just one curiosity.

The first thing I look for, Brett told Sports Illustrated, is to see who is below the Mendoza Line.

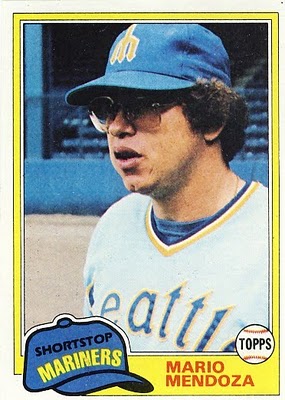

Brett continues to receive much of the credit for coining The Mendoza Line, named in dishonor of Mario Mendoza, the shortstop for the 1979-80 Seattle Mariners, who is not only synonymous with feeble batting, but feebleness across a spectrum of pursuits.

The Mendoza Line, the figurative boundary in the batting averages between those hitters above and below. 200, didnt actually start with Brett, as Mendoza himself explained in a 2010 interview from his home in Sonora, Mexico.

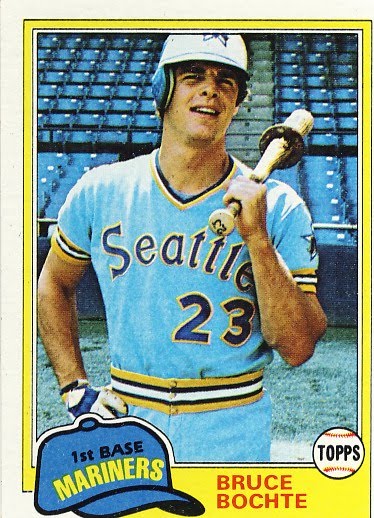

“My teammates Tom Paciorek (1978-81) and Bruce Bochte (1978-82) used it to make fun of me,” said Mendoza. “Then they were giving George Brett a hard time because he had gotten off to a slow start that year (1980). They told him, ‘Hey, man, you’re going to sink down below the Mendoza Line if you’re not careful.’

Paciorek has always denied being the originator of “The Mendoza Line,” insisting in a number of interviews that it was Bochte’s idea. Bochte has never denied Paciorek’s assertions. In any case, The Mendoza Line so resonated with Brett that, early in the 1980 season, he mentioned it to Chris Berman of ESPN, the Bristol, Conn.-based cable network then in its second year of operation. In turn, Berman and other ESPN anchors began using The Mendoza Line on SportsCenter as a humorous way to describe struggling hitters.

ESPN’s repeated use of “The Mendoza Line” spread the phrase nationwide and eventually fixed it in baseball culture (in the latest edition of Dicksons Baseball Dictionary, eight inches of type is devoted to defining The Mendoza Line) and enabled the player behind its inspiration to supplant Vinko Bojataj, famous for his tumble off the ski jump ramp in the opening scenes of ABCs Wide World of Sports, as the athlete most associated with failure.

The Mendoza Line found traction in other sports and even spawned knockoffs. On Dec. 19, 2006, Jay Heater of the Baltimore Sun, in a piece about college bowl games, wrote: With 32 bowl games this season, only nine bowl-eligible teams (all 6-6) didnt receive bowl bids as they all landed at college footballs Mendoza Line. In 2007, Alexander Wolff of Sports Illustrated described Kordell Stewarts NFL passer rating of 70 as The Kordoza Line.

Today, the Mendoza Line transcends sports. It is used to measure the IQs of death-row inmates, define minimal grade-point averages and minor league hockey attendance below 2,000. Mendoza Line is used in the movie business to characterize a film that has grossed an average of $2,000 or less during a weekend.

A politician whose public approval rating is 20 percent is said to be hovering at the Mendoza Line. (In 2008, when Keith Olberman had a show on MSNBC, he used Mendoza Line after Rudy Giuliani withdrew from the Presidential primaries after garnering only one delegate).

Ironic about Mario Mendoza becoming the poster boy for inept batting is that scores of woodless wonders have performed worse than he did. Mendoza was not the worst hitter of his era, nor is he the worst to wear Seattle flannels.

When Mendoza hit .198 in 1979, the franchise record for lowest single-season batting average was .182 (minimum 300 at-bats), set a year earlier by Leroy Stanton, Seattles designated hitter. Mendoza simply had the ill luck to inspire The Mendoza Line as the cameras went on at ESPN, the sporting equivalent of wandering onto the railroad tracks as the train whizzes by.

A native of Chihuahua, Mexico (also the birthplace of actor Anthony Quinn), situated 250 miles south of El Paso, Texas, Mendoza arrived in Seattle in the aftermath of a Dec. 5, 1978 trade with Pittsburgh, in which the Mariners sent RHP Enrique Romo (the teams first closer), RHP Rick Jones (Jones still holds the franchise record for most walks in a game: issued 11 at Texas on June 18, 1977) and minor leaguer Terry McMillan to the Pirates for Mendoza, RHP Odell Jones and RHP Rafael Vasquez.

Mendoza never hit much as a utility player in Pittsburgh a .204 average in 441 career at-bats dating to 1974 (three partial seasons under .200), but the Mariners were awed by his defensive skills, and they needed a shortstop to replace Craig Reynolds, who had been swapped to Houston for local pitching product Floyd Bannister.

In what became his first full season in the majors (148 games), Mendoza formed an effective double-play combination with second baseman Julio Cruz. In a Sporting News article that year titled Ms Singing Praises of Mendozas Magic Glove, Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski, then a Mariners coach, was quoted as saying, Mario Mendoza is the best shortstop in the American League. Total Baseball came close to agreeing, ranking Mendoza the No. 3 shortstop in the majors. And stats guru Bill James called Mendoza a “truly remarkable fielder.”

Mendoza had his moments at the plate. On June 22, in a 15-8 Seattle loss to the Milwaukee Brewers in the Kingdome, Mendoza became the third Mariner, following Ruppert Jones and Cruz, to hit an inside-the-park home run (off Jim Slaton). He had three hits in a game three times, and three, three-RBI games, May 5, July 11 and Aug. 30.

Unfortunately for the Chihuahuan, he couldn’t produce a hitting streak longer than three games. He had 13 0-for-4s, an 0-for-5, and pretty much sealed his place in history when he finished with a .198 batting average (one more hit would have gotten him to .200) with a .216 on-base percentage, a .249 slugging percentage, and a .466 OPS in 373 at-bats, truly tawdry numbers.

Mendoza also established a Major League record for most games played (148) by a sub-.200 hitter (later matched by Steve Jeltz of the 1988 Phillies).

Use of the term Mendoza Line gained traction early in the 1980 season when Mendoza posted a .176 April batting average, dropping his career mark in Seattle to .192. Mendoza probably didnt know it, but dead ahead loomed the dreaded Ray Oyler Divide, over which only one modern man had crossed.

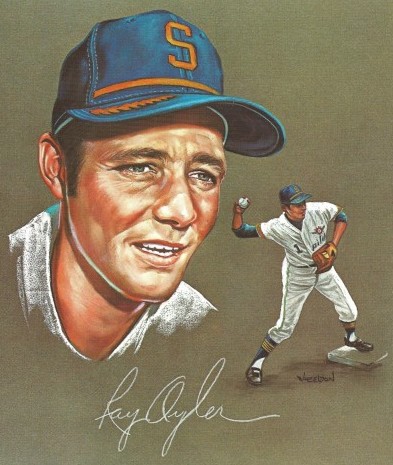

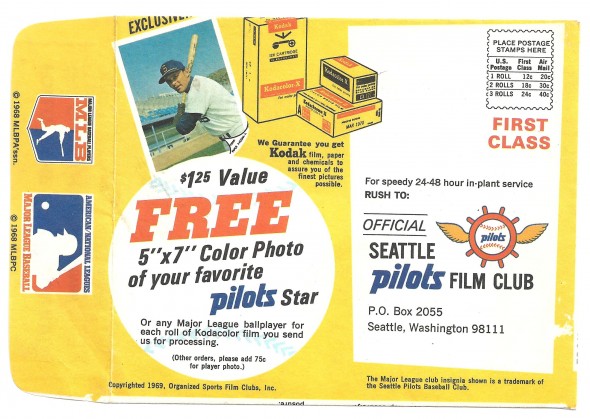

The Mendoza Line not yet coined, Detroit Tigers players used the Ray Oyler Divide to describe the endless batting funk of Raymond Francis Oyler, who parlayed a four-year, .180 average in Motown into a job with the 1969 expansion Seattle Pilots.

That Oyler could amass 1,125 at-bats with the Tigers while hitting .180 speaks to his skill with his glove. Johnny Sain told SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) that Oyler was one of the best fielders he saw in a half-century of playing and watching the game. Detroit teammate and roommate Denny McLain further told SABR that, Ray couldnt hit his way out of a room full of toilet paper with a crowbar, but the way he could field, Id keep him on my club if he couldnt hit his weight.

In fact, the 165-pound Oyler couldnt. He hit just .135 (29-for-247) in 1968, an average so low that it prompted Tigers manager Mayo Smith to make one of the most extraordinary moves in World Series history that year against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Smith benched Oyler and inserted Gold Glove center fielder Mickey Stanley to play Oylers shortstop position for each of the seven games. That enabled Smith to play his four best outfielders, Stanley, Al Kaline, Willie Horton (who hit 29 homers for the 1979 Mariners) and Jim Northrup, all better hitters. After starting for the Tigers all year, Oyler had just one plate appearance in the World Series.

Five days after the Tigers clinched it, and not yet in possession of his World Series ring, Oyler became the property of the Pilots, taken as their No. 3 choice, following Don Mincher and Tommy Harper, in the Major League expansion draft held to stock the Pilots and Kansas City Royals.

Rich Shook, who covered the Tigers for Detroits United Press International bureau, wrote this about Oyler: Almost as soon as a game began, Oyler would come unglued . . . Because Oyler was forever trying to put a power swing on a 5-foot-11, 165-pound body, fastballs defeated him. His head would fly off the ball and hed end up one-handing an upper cut swing that would miss any pitch with the slightest wrinkle in it.

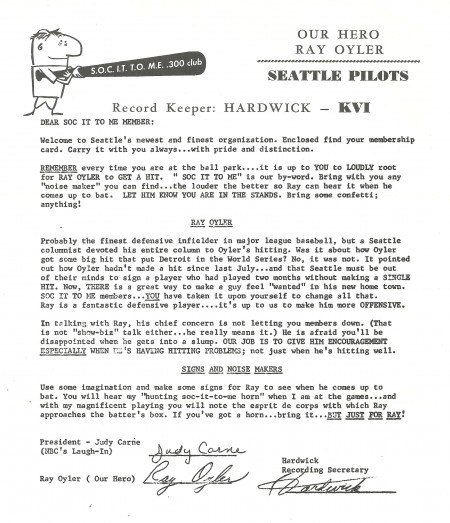

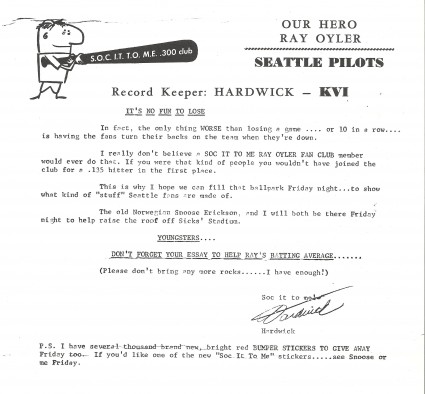

That scouting report especially thrilled Robert E. Lee Bob Hardwick, a Seattle radio personality for KVI (which held the Pilots broadcast rights), who liked to describe himself as a “professional smartass,” and loved pulling stunts. Among other things, Hardwick jet-skied 740 miles from Ketchikan, Alaska, to Seattle and swam the Bremerton-Seattle ferry route.

After scanning the list of players selected by the Pilots in the expansion draft, Hardwick immediately seized on that glaring .180 next to Oylers name. Hardwick probably also noticed that Oyler had not produced a base hit since July 13, 1968, an end-of-the season 0-for-37 schneid that fell just 11 hitless at-bats shy of the MLB record of 46, by Bill Bergen in 1909.

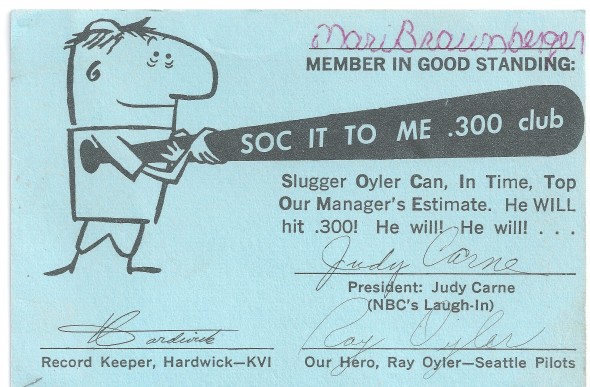

Then, playing off the popularity of the Sock it to Me catch phrase of TVs Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In, Hardwick created the Ray Oyler S.O.C. I.T. T.O. M.E. .300″ Club. That meant “Slugger Oyler Can, In Time, Top Our Manager’s Estimate” and hit .300.

The Ray Oyler Fan Club wrote and sang songs, such as “Hey Ray Oyler yer Bat’s Too Small,” and provided Oyler with an automobile.

Once, after Jim Campanis of the Royals punched Oyler during a game, the Ray Oyler Fan Club dispatched a telegram to Kansas City general manager Cedric Tallis, protesting Campanis’ goonery, saying: “Please do not misinterpret our motto ‘Sock it to Ray Oyler,’ as this is an expression of encouragement.”

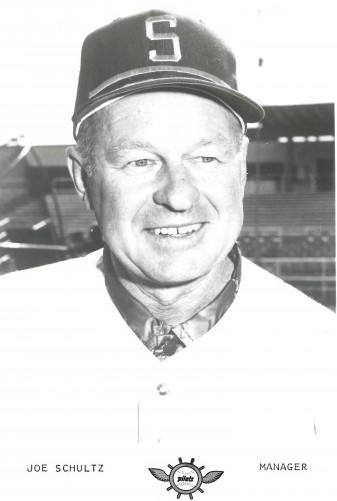

Asked by reporters during 1969 spring training whether Oylers anemic hitting would be a liability (dumb question!), Pilots manager Joe Schultz responded, Ah, hell. Ray Oyler will bat .300 for us with his glove. (BTW: Schultz led the American League in Ah, hells in 1969).

Eventually, Hardwick got thousands of listeners (estimates range between 5,000-15,000) of his radio show to join the fan club. When Oyler came to bat for the first time in Sicks Stadium on April 11, 1969, cheers rang out, horns tooted and confetti rained. Oyler went 1-for-3 with a walk, and one night later (April 12) he sent 8,000 fan club members into a dither when he socked a solo homer off Sammy Ellis in what became a 5-1 Pilots victory over the White Sox.

Oyler hit .350 during his first week with the Pilots and finished the season with seven home runs, a career high (for years, Ray Oyler fan club members boasted humorously that their hero still held the all-time Pilots record for home runs by a shortstop).

But he also hit .165 (exactly his weight!) 30 points higher than he had hit with the Tigers in 1968 (five of his seven home runs came at cozy Sicks Stadium), but 35 points below The Mendoza Line, which wouldnt exist until 11 years later.

Thirty-five points below The Mendoza Line seems to be roughly the location of the Ray Oyler Divide (Oylers Detroit teammates never defined it beyond whatever Oyler happened to be hitting at the moment, which was never good).

This begs two questions: What are the odds of two Seattle teams winding up with two of the worst hitters in baseball history just a decade apart, and which was worse, the Pilot who hit more than .200 just once in six seasons, or the Mariner who hit less than .200 in five of his nine campaigns?

As to the first question, we cant say other than to note that it probably figures, given Seattle’s historic penchant for sporting mediocrity (on the other hand, Seattle is the only city to simultaneously sport Major League Baseballs single-season record holder in hits — Ichiro, 262, 2004 — and the NFLs single-season record holder in touchdowns — Shaun Alexander, 28, 2005). As for the second, it depends on how the numbers are diced.

Oyler compiled a .175 career batting average, the lowest of any player to step to the plate at least 1,000 times since the deadball era. Oylers .135 average in 1968, the year before he joined the Pilots, represents the worst in the majors since Bill Bergen, by acclamation the worst hitter in history, hit .139 in 1909.

Of the 20-odd players who finished their careers with at least 1,000 plate appearances and a batting average below .200, Oyler has one of the lowest OPS+ marks — 48 (On Base + Slugging Percentage adjusted for the park and the league in which the player played). An OPS+ of 150 or more is exceptional (Ted Williams, 190), 125 very good (Ken Griffey Jr., 134) and 75 or below not so good (Willie Bloomquist, 75).

But among non-pitchers with more than 1,000 plate appearances, Mendoza ranks No. 2 (behind Bergen’s 21) on the list of lowest career OPS+ at 41, according to Baseball Reference’s Player Index tool.

Stats aside, perhaps Bruce Nash and Allan Zullo, authors of the amusing “The Baseball Hall of Shame” series, published in the late 1980s, make for the best arbiters of the “Who was the worst?” question. They researched thoroughly more than a century of hitless wonders. In their book, the first “hitless wonder” they profile is Mendoza, second is Bergen, and third is Oyler, about whom Nash and Zullo write, “Ray Oyler was born to be an easy out. He lived in a slump his entire major league career, becoming the pitcher’s best friend.”

This is how Oylers 1969 season with the Pilots compares to Mendozas 1979 season with the Mariners (while Oyler’s batting average was worse, his OPS+ was better):

| Year | Player | G | AB | R | H | Avg. | OBP | SLG | OPS | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Oyler | 106 | 255 | 24 | 42 | .165 | .260 | .267 | .526 | 50 |

| 1979 | Mendoza | 148 | 373 | 26 | 74 | .198 | .216 | .249 | .466 | 25 |

This is how Oylers career (1965-70) compares with Mendozas (1974-82). Note how similar they are in OPS (on base plus slugging):

| Years | Player | G | AB | R | H | Avg. | OBP | SLG | OPS | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965-70 | Oyler | 542 | 1265 | 110 | 221 | .175 | .258 | .251 | .508 | 48 |

| 1974-82 | Mendoza | 686 | 1337 | 106 | 287 | .215 | .245 | .262 | .507 | 41 |

Just for the fun of it, and recognizing that the Mariners still have a lot of baseball left this season, this is how Chone Figgins to date compares to Oyler’s 1969 and Mendoza’s 1979:

| Year | Player | G | AB | R | H | Avg. | OBP | SLG | OPS | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Oyler | 106 | 255 | 24 | 42 | .165 | .260 | .267 | .526 | 50 |

| 1979 | Mendoza | 148 | 373 | 26 | 74 | .198 | .216 | .249 | .466 | 25 |

| 2011 | Figgins | 59 | 231 | 20 | 44 | .190 | .239 | .255 | .494 | 42 |

Oddly, no sooner did Chris Berman and his studio mates make The Mendoza Line infamous in early 1980 than Mendoza began distancing himself from it. After hitting .176 in April, he batted .400 in May and .292 in June. Although Mendoza hit just .205 the rest of the way, he finished at .245, a career high.

Traded by the Mariners to the Texas Rangers on Dec. 12, 1980, as part of a 12-player package, Mendoza ended his Major League career two years later with a .215 career batting average and culturally branded forever as a symbol of futility.

According to numerous interviews he gave after returning to Mexico, where he is a member of the Mexican League Hall of Fame, Mendoza resented for a long time the notoriety he received from The Mendoza Line.

“It did bother me, at the beginning, to be honest,” Mendoza said in a 2010 interview. “Because people would come up to me, like making fun of me, so it used to make me mad, but now I don’t care anymore.”

A sidebar to all of this is that both Mendoza and Oyler could have played with Rick Auerbach, listed by Baseball Reference as one of the 10 batters most similar to Mendoza (.220 career batting average), who is one of the 10 batters most similar to Oyler.

The Seattle Pilots selected Auerbach in the seventh round of the 1969 draft (January phase). Auerbach spent that season in the Pilots minor league system (Billings of the Pioneer League and Clinton of the A Midwest League) and didnt reach the majors until 1971, after the Pilots had relocated to Milwaukee and Oyler had moved to the Pacific Coast League to finish his career.

Eventually, Auerbach landed in Texas, which swapped him to the Mariners on Dec. 12, 1980, in a trade that included Mendoza, who played two years (1981-82) with the Rangers before returning to the Mexican League, where he hit between .246 and .316 over the next seven seasons (from 1992-07, Mendoza managed in the California League, Texas League and Mexican League).

Seattle made a lasting impression on Oyler, despite his having spent only six months in the city. When his career ended (with the Hawaii Islanders), he moved to Bellevue, and went to work on the loading docks at Safeways Distribution Center in Redmond, frequently pitching produce, and always wearing the World Series ring he earned in 1968 with Detroit.

For the next several years, Oyler also sold automobiles, peddled insurance, managed a bowling alley, worked for Boeing and poured out publicity for the World Fastpitch Assn., an aborted attempt to professionalize softball.

Oyler itched to get back into baseball as a coach when the Mariners came to town, and submitted his resume to them, but no offer came. Before one could, Oyler died of a heart attack (Jan. 26, 1981) at the age of 42.

In an odd way, Oyler lucked out. Had ESPN gone on the air a decade earlier (1969) than it did (1979), the catch phrase “Ray Oyler Divide” might have trumped “The Mendoza Line.” Instead, Mario Mendoza played with Tom Paciorek and Bruce Bochte, who talked to George Brett, who gossiped to ESPN, which spread the word, and Mendoza became Vinko Botataj in perpetuity.

Check out David Eskenazis Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

10 Comments

Now maybe we could introduce into national vocabulary the term “Mariners’ way.” I don’t think it needs any explanation.

Actually, though, I really enjoyed this piece and at one past point was going to suggest something covering the Mariners’ first season including spring training, etc., and this story has a few of those type of elements, at least with regard to the era of Mariners’ baseball it mostly addresses. Beside, back then their ineptitude was almost lovable and expected.

Michael: Thanks for your response. It is much appreciated.

Now maybe we could introduce into national vocabulary the term “Mariners’ way.” I don’t think it needs any explanation.

Actually, though, I really enjoyed this piece and at one past point was going to suggest something covering the Mariners’ first season including spring training, etc., and this story has a few of those type of elements, at least with regard to the era of Mariners’ baseball it mostly addresses. Beside, back then their ineptitude was almost lovable and expected.

Gentlemen,

This is an excellent piece of baseball history.The detailed documentation, pictures and comparative stats make for a deep storyline, told artfully.

Thanks so much for visiting our web site.

Gentlemen,

This is an excellent piece of baseball history.The detailed documentation, pictures and comparative stats make for a deep storyline, told artfully.

This is just beautiful. One of the best pieces on this site that I’ve read in a while. (Yeah, it’s been up here a while. I’m slow.) It brings me back to the days of listening to the gross ineptitude of the early Mariners (kind of like now). At least back then the baseball characters had more, er, character.

Very nice work.

This is just beautiful. One of the best pieces on this site that I’ve read in a while. (Yeah, it’s been up here a while. I’m slow.) It brings me back to the days of listening to the gross ineptitude of the early Mariners (kind of like now). At least back then the baseball characters had more, er, character.

Very nice work.

Can you name the other five ex-Mariners?

I’m watching the Dodger-Mets gameon ESPN. The Dodge shortstop just made two errors in a row. The announcers were quite oen about them looking for talent at s/s. Since the Mariners are going young, why not dangle Ryan. We might get a premium prospect. Kawasaki wouldprobably do just fine with more playing time.