By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Imagine the blabber-jabber fest that would erupt on sports talk radio today if the Seattle Mariners had a big, popular home run hitter and traded him to a division rival for that clubs leading banger — and got a starting catcher in the bargain.

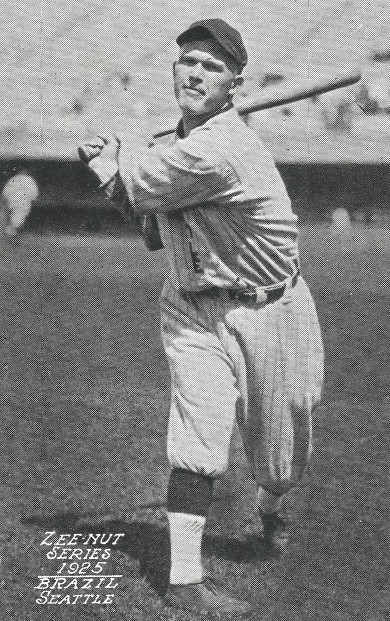

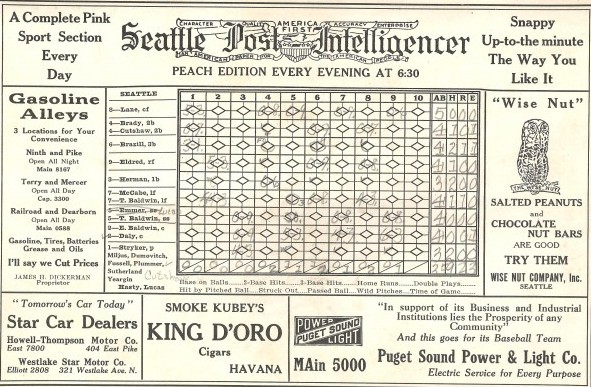

A trade exactly like that occurred Nov. 23, 1924, when the Seattle Indians dispatched Ray Rohwer, who had clubbed 33 home runs for the 1924 Pacific Coast League champions, to the Portland Beavers for infielder Frank Leo Brazill, a thumper coming off a 36-homer, .351 batting campaign, and catcher Tom Daly.

In the absence of talk radio, Seattle (and Portland) newspapers carried dozens of articles about the winter swap, most (predictably) focusing on which team got the better of it.

The short answer: For one year Seattle did, as Brazill delivered one of the stupendous batting seasons in PCL history.

The long answer is a bit more complicated, owing to the fact that following the 1925 season, Brazill became the main operative in one of the biggest local baseball soap operas of the 1920s (one reminiscent of Alex Rodriguez’s jump from Seattle to Texas in 2000).

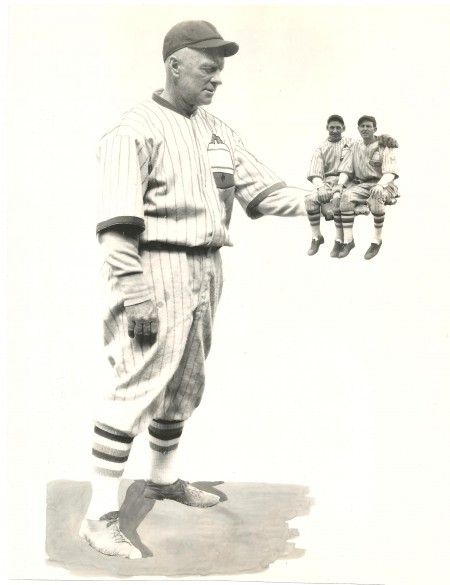

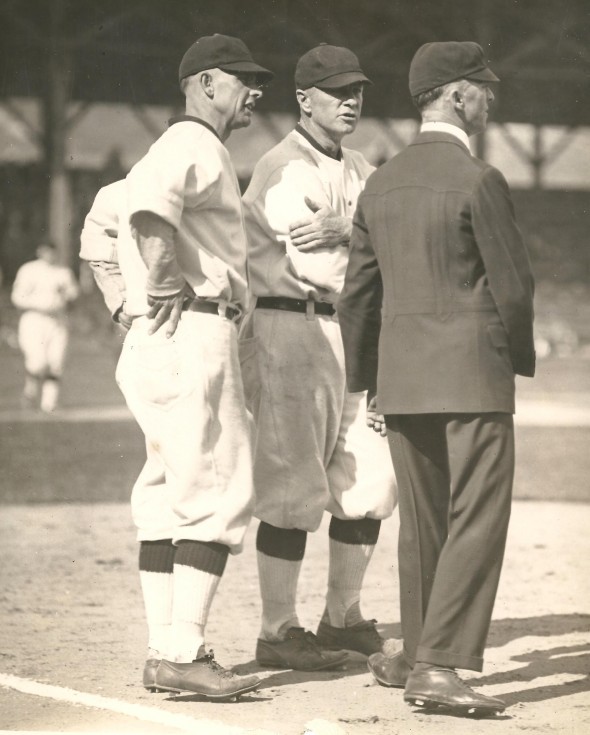

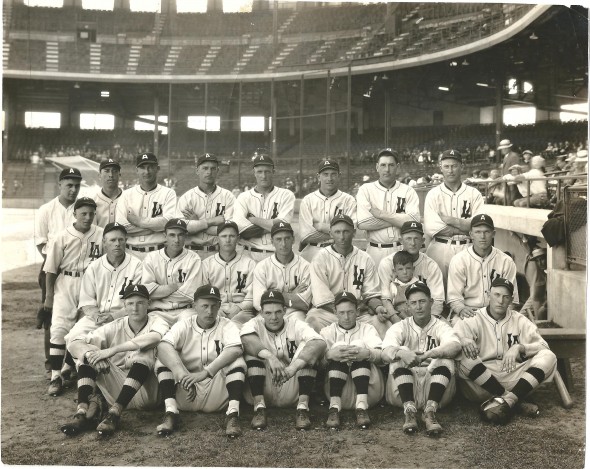

As the winter of 1924 approached, Indians president Charles Lockard and manager Wade ”Red” Killefer determined that the roster over which they presided required a major overhaul — despite the fact the Indians just won their first PCL pennant with a 109-91 record.

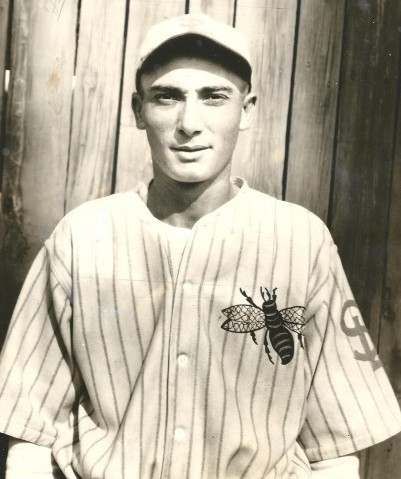

For a variety of reasons, most involving a limited club payroll, nine members of that title team would not return to the Indians in 1925 (Vean Gregg, the big winner in 1924 with a 25-11 record, moved to the Washington Senators), so Lockard and Killefer had a lot of player acquisitions to make. One of their first was the signing of first baseman Babe Herman, who hit .349 at Class A San Antonio in 1924. But the trade for Brazill and Daly on Nov. 23 represented their most significant — and controversial – move.

Indians fans took a liking to the 5-10, 155-pound Rohwer, who had spent the 1921-22 seasons with the Pittsburgh Pirates and 1923-24 with Seattle, where he hit .325 both years with 37 and 33 home runs, respectively. But Killefer believed Brazill to be Rohwer’s superior at the plate and a better gate attraction.

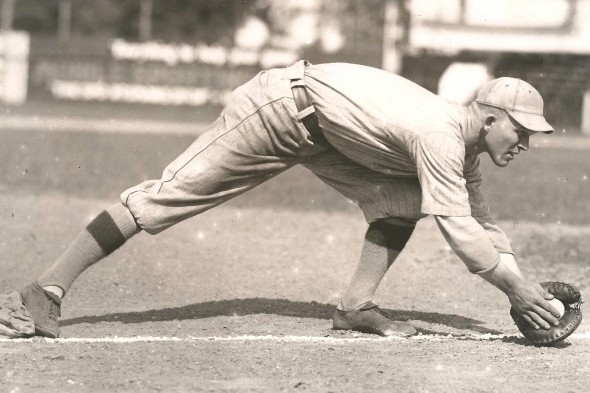

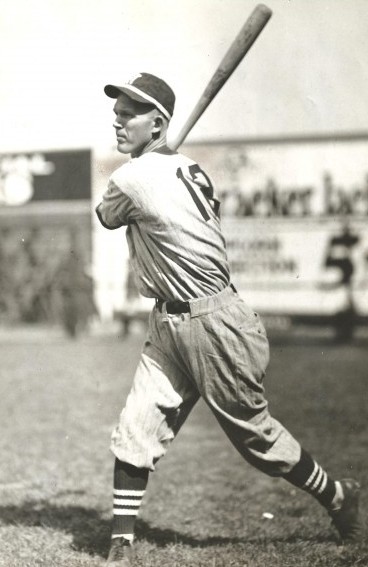

A native of Spangler, PA., Brazill had also had a brief run in the major leagues, with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in 1921-22 (72 games, .258 batting average; had a 3-for-4 game on Sept. 23, 1921, against the Cubs at Shibe Park). And while he walloped 36 home runs in Portland, he came to Seattle with the same liabilities that had cost him a chance to stick in the majors: poor defensive skills and a weak throwing arm.

According to the newspaper, Brazil practically “had to wind up” to propel the ball from third base to first. Wrote the Times: ”Why doesn’t some major league team take Brazill? His arm, injured in Atlanta in 1920, and hurt again in 1921 when he played for the Athletics, is his one drawback. You’ve pretty nearly got to see the rifles these big leaguers use to understand the difference between a minor and a major leaguer.

“In obtaining Brazill, along with catcher Tom Daly, Killefer got a man who is equally popular in Seattle even if he has been wearing a foreign uniform. There isn’t a ballplayer in the Pacific Coast League who hustles harder than Brazill. He is only a fair fielder, but his big bat drives in so many runs that his fielding shortcomings are overlooked.”

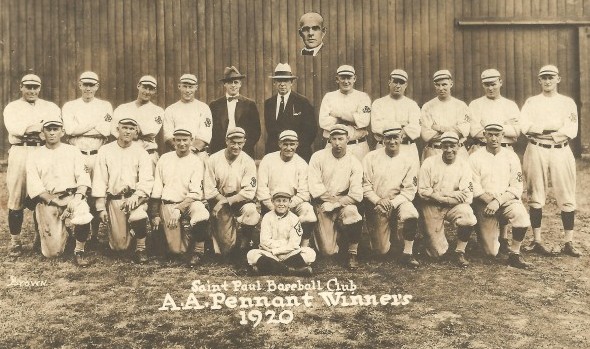

In the weeks leading up to spring training, Seattle newspapers made much of Brazill’s already-extensive career. He started playing professionally in 1918 for Cumberland in the Maryland League, after which the Brooklyn Dodgers, having heard of his hitting feats, signed him as a free agent. The Dodgers placed him with Hartford (Eastern League) and Winnipeg (Western Canada League) for seasoning in 1919. A year later, when the Dodgers waived him, Connie Mack claimed Brazill and placed him with first Atlanta (Southern Association) and then with St. Paul (American Association).

In 1921, with the Athletics, the left-handed Brazill spent weeks on the injured list (throwing arm), but when he did see action, his hitting had been so impressive that Mack felt he had a chance to become a star.

“He puts life into the game,” the Philadelphia Public Ledger wrote April 16, 1921. “They are still talking about his nervy play when he stole home on Thursday. Nobody knew anything about it except Brazill. Danny Murphy, who was coaching at third, was taken by surprise as were the New York players and Connie Mack. Connie almost fell off the bench when he saw his first baseman streaking for home because stunts like that never are pulled by the Athletics. The skinny leader (Mack) passed away when Brazill was declared safe. The surprise was too much.”

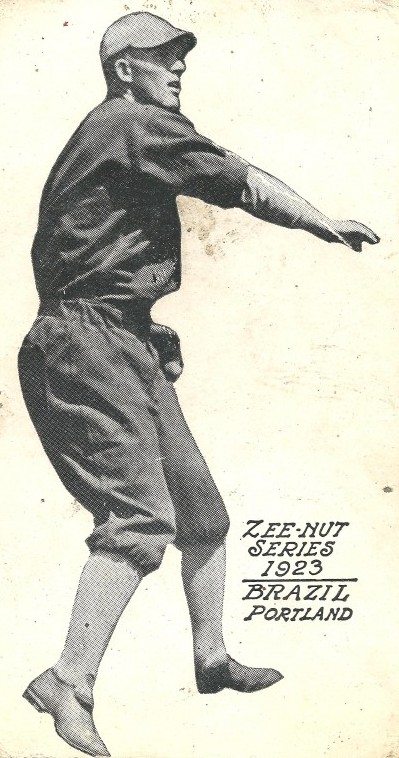

When, a year later, Brazill had failed to become anything more than a fill-in, Mack dispatched him to Portland (May 15, 1922), where he remained until his trade to Seattle (became a teammate of Jim Thorpe’s that year).

“Brazill performed the highly unusual feat of playing in three leagues in 1920 and ranked with the leaders in all three of them,” the Times observed in its introduction of Brazill to Indians fans.

”Philadelphia had him at the start of the season but released him to Atlanta, which sold him to St. Paul in mid-July. With the Athletics he hit .350 (spring training), with Atlanta .333 and with St. Paul .378.”

An off-season life insurance salesman, Brazill expressed gratitude that Killefer had traded for his services: ”I would rather play for Killefer than any man I know in baseball. I like Seattle too. I will be there a long time.”

When the Indians reported to spring training in Santa Maria, CA., in mid-February of 1925, Brazill offered a forecast of his season, saying, ”I have a bat here that just naturally exudes base hits.”

Brazill, who fancied himself a writer and a poet, loved to tell stories, making him a favorite of the reporters who covered the Indians for Seattles newspapers. Brazill had this one about his time with the Philadelphia Athletics:

“Ty Cobb was my ideal from the time I first began reading the big league box scores. And it was my good fortune to join the Philadelphia Athletics for my first big league tryout when the Athletics were engaged in a series with the Detroit Tigers.

“I arrived in the morning of the first game and was given a uniform and worked out in the infield practice at first base. Connie Mack was giving a lot of the youngsters their first chance and the scorecard carried me as the first baseman that day.

”However, during the infield workout, I became dizzy, had to quit, and went to the clubhouse where the trainer worked on me for more than an hour before I came around and got back into my street clothes.

“Meantime, the game went on, and Johnny Walker, a rookie from Omaha, played first base. Johnny wasn’t a bit bashful about saying what he thought and the great Tyrus that day happened to draw the fire of his chatter.

“The next day I came back and as I stepped out of our dugout, Cobb was hitting. He spied me, dropped his bat, came over to me and gave me the worst panning I’ve ever received. Before the idol of my boyhood days, I couldn’t say a word. I took it all in silence.

“Joe Dugan, now a third sacker for the Giants, went to Ty and told him he was mistaken, that I hadn’t even been in the game. But Ty Cobb wasn’t man enough to apologize, and my boyhood idol was broken right there.”

Brazill almost didn’t make it out of spring camp with the Indians. The Chicago Cubs called Killefer and outlined the terms of a trade, but Killefer didn’t believe the Cubs offered enough, especially in terms of pitching, and turned them down.

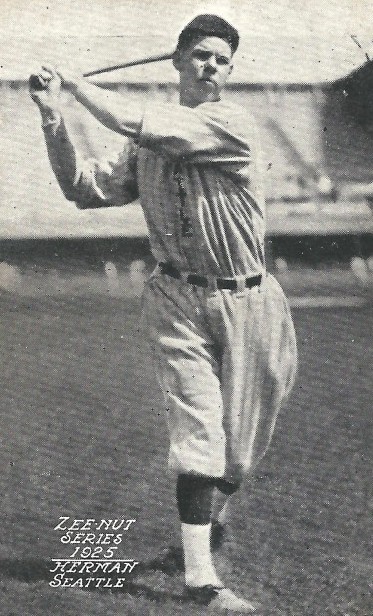

So Brazill opened 1925 as the Indians third baseman and had a start even beyond Killefers expectations.

In the first three games, Brazill had six hits in 13 at-bats and every one of his hits “was a crashing drive that left no doubt as to whether they were legitimate base knocks,” noted the Times. ”Three of them rattled off the fence, another cleared the fence with yards to spare while the others were singles through the (San Francisco) Seal infield.”

Brazill produced multiple-hit games in almost every Indians contest up to April 22 (all on the road), when, in Seattle’s home opener in front of 12,500 fans at Dugdale Park, he hit a three-run homer, a single, a sacrifice fly, scored three times and performed the remarkable feat of scoring from second base on a sacrifice fly.

Wrote The Times: “(Ross) Brick Eldred supplied the power behind the sacrifice fly. In the seventh inning (against the Vernon Tigers), Eldred hit a terrific drive to center field that (Eddie) Moore caught on the dead run. The ball was hit so far that Brazill scored, standing up, from second base.”

On April 30, Brazill had two doubles and two singles in a 7-3 win over the Oakland Oaks, and by May 5 was hitting .431 – 47-for-109 – with Seattle’s second-best hitter, Eldred, far back at .310.

In an 8-5 win over Portland May 5, Brazill pounded three long home runs, all to right field. Three days later (May 8), he ran his hitting streak to 20 games with a 3-for-3 effort in a 4-2 loss to the Beavers.

Brazill extended his hitting streak to a season-high 26 games May 14 (teammate Eldred also had a 26-game hitting streak in 1925), by which point his batting average stood at .424 (60-for-142) with nine home runs.

Although still early in the season, both Seattle newspapers started to sense that the PCL batting race was shaping up as one of the best in years.

On the day Brazill’s average stood at .424, San Francisco’s Paul Waner (who later became a Hall of Famer after starring with the Pittsburgh Pirates) checked in at .399. Lefty ODoul and Tony Lazzeri, both of the Salt Lake Bees, had .375 and .355 marks, respectively.

Waner moved into first place May 24 with a .424 mark after Brazill dropped to .422. Brazill then tailed off for five weeks, his average dipping to .397, but on July 7 he came through with a 5-for-5 show in an 11-3 win over the Sacramento Solons (Killefer’s brother, “Reindeer Bill,” managed this franchise from 1936-38).

First time up, Brazill homered over the right field fence. Second time up, with Billy Lane perched on second, Brazill knocked another one over the right field fence. Third time up, he punched an RBI single to left. Fourth time up, batting leadoff, he singled. Fifth time up, Brazill produced an RBI single, driving in Bob Hasty. Brazill finished the day with a .409 season batting average.

A week later (July 13), Brazill again found himself leading the PCL in batting at .412 with Waner at .408 and ODoul at .404.

Brazill had his last big day at the plate Aug. 11, banging four hits in a 9-5 victory over Vernon, placing his average at .405.

Finishing at .395, Brazill did not win the batting title. Waner hit .401. But Brazill ended with 280 hits in 185 games, a league-leading 67 doubles, 11 triples, 29 home runs, and a .644 slugging percentage, one of the best batting years by any Seattle professional.

The Indians had three big hitters in 1925. In addition to Brazill, Eldred hit .327 and Herman (purchased by the Brooklyn Dodgers after the season), .316 (Herman would become the only major leaguer to three times hit for the cycle). Despite that, and the 20 wins notched by staff ace Johnny Miljus, the Indians (103-91) came up short in the pennant race.

In an attempt to overtake San Francisco, Killefer tried out a dozen new players late in the season in hopes of establishing momentum. Nothing worked. Killefer became so upset that he drew three suspensions for arguing with umpires (pity the ump when Killefer, a garlic chewer, got in his face).

When, on Sept. 5, it became obvious the Indians would not win the pennant, Killefer inserted Wally Krauklis, a Seattle fan from the stands, into the line-up against the Angels. Krauklis went hitless in three at-bats in an 18-2 Seattle drubbing.

Killefer’s moves probably wouldn’t have made much of a difference anyway as the Waner-led Seals won a franchise-record 128 games (lost 71). None of Earl Averill’s (1926-28) or Joe DiMaggio’s (1932-35) San Francisco teams won that many in a year.

The Indians had every expectation of employing Brazill in 1926, but two weeks after Lockard mailed Brazill his new contract, Lockard got it back – unsigned, ripped to shreds, and with no accompanying explanation. Brazill’s act infuriated Lockard and almost all Indians fans, once word was out.

”Brazill’s business ethics are not the best,” the Times opined in a front-page screed.

Brazill refused to make himself available for comment, but Lockard couldn’t contain himself.

”Under the circumstances there will be no further negotiations with Brazill from the Seattle club,” said Lockard. Brazill was one of the best-paid players in the Pacific Coast League last season. He made an issue out of his transportation, in which we gave in to him, too. Then, after using the transportation as far as Portland, he attempted to turn the balance back to the railroad company only to find that if he did not use it, it reverted back to the baseball club.”

Brazill made a reported $800 per month during the 1925 season, near the top of the PCL salary scale. He became upset (or was told he should be upset) with the Indians for two reasons: He believed the Indians should have paid his way to his native Pennsylvania during the offseason and claimed they had not. More than that, the Indians had not offered Brazill a raise for 1926 despite a .395 average and 29 home runs.

“Brazill’s latest act makes it impossible for me to deal further with him,” said Lockard. ”The tearing up of the contract that we sent him cannot be condoned. It was for the same money he received last year. If there is anything more to be made of this situation, it must come from him.”

Later that winter, Lockard and Killefer traveled to Southern California to attend some Los Angeles Winter League games, including one in which Brazill played. When Brazill discovered that Lockard and Killifer had been in attendance, he broke his silence by saying of Lockard, ”He better get his pencil out and do some figuring if he expects me to play for him again.”

As the days passed with no further word from Brazill, the Indians came to suspect that one, or more, PCL clubs, not yet identified, had tampered with Brazill. That suspicion soon found its way into Seattle newspapers.

“It is just possible,” the Times wrote. “Tampering is one of the recognized evils of baseball for which a club is continually on the lookout.”

Bill Klepper, a former owner of the Portland franchise (and a future owner of the Seattle Indians), had once been found guilty of tampering with Bill Kenworthy by attempting to lure the manager of the Seattle team to Portland.

In one of the famous tampering decisions of the era, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis banned Klepper from baseball for life, a decision which was overturned years later when Klepper came up with enough cash to purchase the Seattle franchise.

”There is more than a suspicion that another Coast League club would like to have Brazill and that Bill would like to play in parts not located in the confines of the state of Washington,” the Times reported.

Between January and April of 1926, Seattle newspapers bulged with stories about the Indians-Brazill feud. They printed every fact, speculation and rumor attendant to the daily drama in order to sate curious fans (who had sided with Indians ownership against the greedy Brazill) and fill news columns.

Not long after the Indians arrived in Hermosa Beach, CA., for 1926 spring training, the Times began to speculate that Brazill would be traded to St. Paul of the American Association for a pitcher and an infielder, both unidentified. Brazill couldn’t verify that such a possibility existed, but immediately acted to gum the works.

“I wont go,” Brazill told the Los Angeles Times. ”I can’t stand the (Midwest) heat and neither can my wife. Ill retire first and get a job.”

Brazill’s comments mostly amounted to bluster because Brazill soon sought a meeting with Killefer. Brazill outlined his demands and asked Killefer to relay them to Lockard. But Killefer, dubbed ”Radiant Red” and “Lollypop” by the Seattle media, said, ”No Class AA club could afford to pay the slugger what he thinks hes worth.”

On March 18, the St. Paul club issued a statement saying it was no longer interested in trading for Brazill after Brazill wired the team that he would not report under any circumstances.

Then the Los Angeles Angels jumped in with a $10,000 cash offer (no players) for Brazill, but Lockard and Killefer rejected it. They wanted players, not cash.

”Every Seattle fan feels that you people have made Brazill dissatisfied by your tactics in this case and I wouldn’t think of selling him to you for cash,” Killefer told Angels boss J.H. Patrick. “If you get me the men I want, you can have him, but only then.”

With the Angels unable to come up with the right package of players, Killefer tried again to lure Brazill back to Seattle with a new contract offer, saying, ”I feel that we have treated Brazill fairly, and I know that we can’t do what he wants. If he doesn’t sign the latest contract I sent him, he can go on the suspended list and stay there until he changes his mind.”

Brazill said he was fine going on the suspended list, and then the Angels raised their offer from $10,000 to $15,000.

The matter came to a head when Brazill told the Los Angeles Times that he wanted to play only for the Angels, and also when he said, ”The Seattle club didn’t appreciate the ONLY clean-living, hustling ball player it had last year.”

With that statement, Killefer knew that Brazill’s days in Seattle had ended. Brazill had alienated his teammates and if Killefer brought Brazill back, he would not have a club that would play together. The Angels apparently recognized that as well and lowered their $15,000 offer to $10,000.

Killefer reluctantly accepted, and Brazill joined the Angels. With Brazill batting .336 with 19 home runs, the 1926 Angels won 121 games and captured the PCL title. Minus their big hitter, the Indians went 89-111 and finished seventh.

No telling what the Indians did with the $10,000 they received for Brazill, but the Seattle Baseball club played 11 more seasons as the Indians, never finishing higher than third and usually languishing in sixth or seventh place.

Brazill never again approached the numbers he posted in 1925. He lasted just two years with the Angels, played his last year at the AA level in 1928, and then commenced a rapid descent into the lower minors, ending his career with Class C Fort Smith of the Western Association in 1938.

After his playing days, Brazill became a minor league manager with Greenville (East Dixie League), Nashville (Southern Association), Greenwood (Cotton States League), Fort Smith (Western Association), Memphis (Southern Association) and, going full circle, with Portland (PCL) in 1942.

One of Seattle’s greatest one-year wonders, Brazill entered the PCL Hall of Fame in 2007, 31 years after his death in Oakland, CA., at the age of 77.

Check out David Eskenazi’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

7 Comments

Thanks for the interesting, well written story.

Thanks for the interesting, well written story.

Great story!! My late gramps.. Frank Cox was a catcher for the Indians.. So this story caught my eye

Great story!! My late gramps.. Frank Cox was a catcher for the Indians.. So this story caught my eye

Very interesting. Makes me appreciate my Frank Leo Brazill signature mini bat even more.

Very interesting. Makes me appreciate my Frank Leo Brazill signature mini bat even more.

I think he might have better luck convincing upper management to move in the fences at Safeco. Now, the weather, that’s another problem altogether.