By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

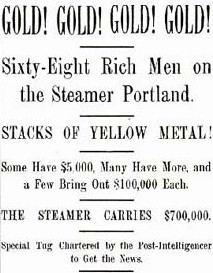

On July 17, 1897, the steamship S.S. Portland arrived in Puget Sound carrying 68 miners and, according to a special edition of that morning’s Seattle Post-Intelligencer, ”more than a ton of solid gold in her hold.” The newspaper’s frenzied headlines screamed Gold! Gold! Gold! Gold! and Stacks of Yellow Metal! A few of the sourdoughs (prospectors) on board the S.S. Portland had bags of gold worth $100,000.

News of the strike along the banks of the Klondike River in the northwestern corner of the Canadian Yukon, which first reached Seattle via telegraph, triggered a massive stampede to the Queen City, largely because of Erastus Brainerd, who worked for the newly founded Bureau of Information, part of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce.

As secretary and executive officer of the BOI, Brainerd became one of the most prominent figures (if not the most) in the national publicity barrage that established Seattle’s preeminence as a mercantile and outfitting center for the miners bound to the Yukon (within a year of the gold strike, Seattle had become as well-known as San Francisco).

Over the next decade, tens of thousands of would-be miners from all over the world purchased millions of dollars of equipment, pack animals, clothing, food and steamship tickets, permanently reshaping Seattle’s economy.

The stampeders, as the Post-Intelligencer referred to them, included a Midwesterner named Daniel E. Dugdale, who had apparently either decided that the lure of gold was too tempting to resist, or that his life in professional baseball had run its course, or perhaps both. We don’t know for sure.

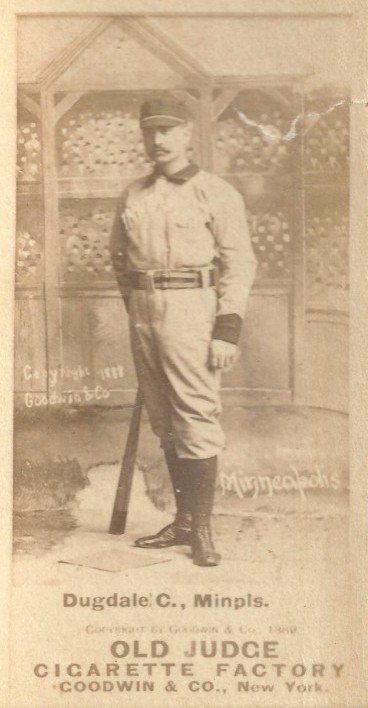

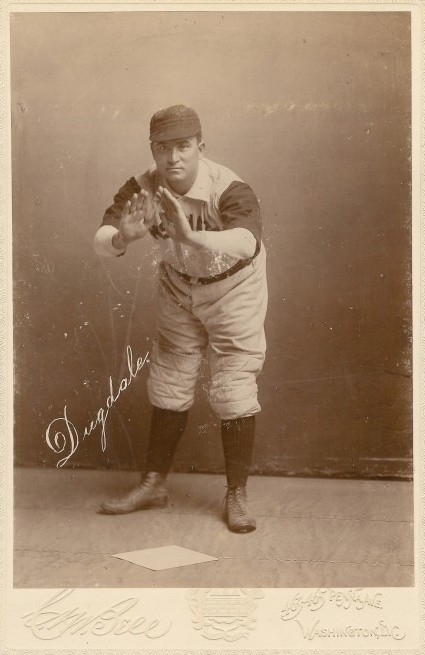

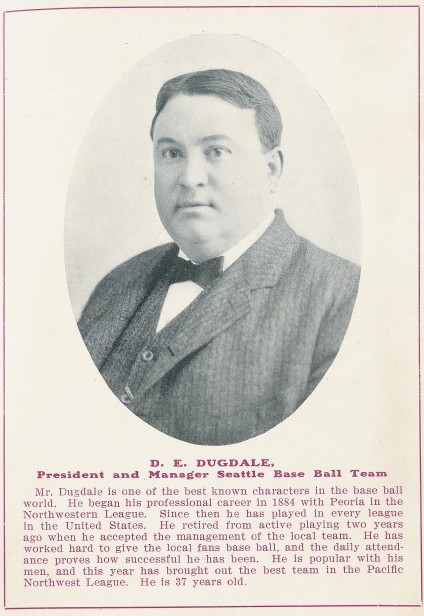

Nor do we know much about Dugdale prior to his entry into professional baseball. Born in Peoria, IL., Oct. 28, 1864, the son of Irish immigrants, Dugdale began his athletic career as a teenaged batboy with his hometown Peoria Reds, and then as a 20-year-old catcher with the club in 1884.

As with many players of his day, Dugdale became an accomplished nomad. Over the next dozen years, he played with 20 ball clubs, most of them in the Western Association, in 13 states. He played in places as small as Leavenworth, KS., Spalding, MS., and Green Bay, WI, and as large as Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Minneapolis.

According to the statistics available about his career, Dugdale never hit much, usually in the .220-.240 range, but showed enough defensive ability – most who saw him rated him a top-notch catcher — that he received two looks in the major leagues.

Dugdale made his big league debut May 20, 1886, appearing behind the plate on behalf of the Kansas City Cowboys (went out of business in February, 1887) against the New York Giants (Dugdale uncharacteristically collected two base hits). But he got into just 12 games for the Cowboys that year, hitting .175, after which he returned to the minors in a variety of out-of-the-way places.

Dugdale received his second major league opportunity in 1894, when he had a 38-game run with the original Washington Senators (hit .239) as a backup to Deacon McGuire, one of the better catchers of the era.

Apparently having no desire to serve as a backup to McGuire again in 1895, Dugdale asked for and received his release. According to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), Dugdale went to Minneapolis and resumed his off-season career as a molder with the Minneapolis Stove Works (no information on how Dugdale got into that trade).

In 1895, Dugdale returned to Peoria and purchased a stake in the city’s Western Association franchise, called the Distillers (in Dugdale’s time, Peoria was the distilling capital of the world with 22 distillers and a dozen breweries). In addition to owning part of the club, Dugdale served as the team’s manager and starting catcher.

Dugdale completed his third year with the Distillers (1897) when he suddenly abandoned baseball and headed for Seattle, apparently enticed by stories of the treasures coming out of the Klondike. Had it not been for those tales, Seattle likely never would have encountered a man who would become one of its most significant and influential sportsmen.

The 33-year-old Dugdale arrived in Seattle in the early winter of 1898, discovering a city bustling with economic activity. New businesses seemed to spring up daily, many of them outfitters — concerned with equipping and servicing miners bound for the Yukon.

As with many of the estimated 100,000 stampeders who came to Seattle at that time (1887-90), Dugdale not only never reached the Klondike, he never even tried.

No telling what changed Dugdale’s mind. Maybe he, as did many others, blanched at the distance to the gold fields and the physical hardships he would encounter. The sea route involved a 4,000-mile trip via the Pacific, Bering Sea and Yukon River, and the land-sea route included 1,000 ship miles, a hike of 32 miles over mountains, and a paddle of 500 miles down the Yukon River.

Dugdale, whom The Washington Post routinely called Fatty Dugdale when he played for the 1894 Senators, probably would have had a difficult time hauling his 265-275-pounds over the frozen terrain.

Perhaps the cost of a junket – the Royal Canadian Mounted Police required stampeders to carry one years supply of goods before they allowed them to cross into Canada — deterred him.

And maybe Dugdale simply didn’t buy into the wild claims of wealth that were promoted by outfitters (and the Chamber of Commerce) eager to get rich off dreamers who thought they were going to get rich.

Some stampeders struck gold, most did not (one estimate is that only 4,000 individuals found any gold at all.) A sawmiller named John Nordstrom (his story is explained in detail in the Klondike Gold Rush Museum in Pioneer Square) famously brought home $13,000 worth of gold, which he invested in a Seattle shoe store, owned by a cobbler he encountered in the gold fields. The shoe store became the foundation for the Nordstrom department store chain.

On the other hand, Edward Nordoff found wealth without enduring the rigors of the Yukon by supplying miners with goods from the Bon Marche store he had launched in 1890 in downtown Seattle. So Dugdale may have determined that Seattle offered at least as many economic opportunities as speculating for gold thousands of miles away in the wilderness.

When Dugdale arrived, Seattle sported 65,000 residents, nearly double what the population had been a decade earlier, but only a quarter of what the population would be by 1910. Due to gold fever, Seattle had a wealth of jobs, and was expanding rapidly (Seattle’s physical area doubled between Dugdale’s arrival in 1898 and 1910 due to the city’s annexations of land north and east of Pioneer Square).

The downtown area, principally around Pioneer Square, featured many new stone buildings that had replaced the wooden ones that had been consumed by the great fire of June 6, 1889. Seattle also had an elaborate system of street cars and railroads, considered the best on the West Coast.

Seattle had one drawback: not much was cheap. A typical, seven-room house cost $275, or 50 cents per week on a special financing plan. A hotel room ran between 50 cents and $1.50 per night, and a good meal about a quarter. A shave might set a man back one dime and a haircut gouged him for 15 cents.

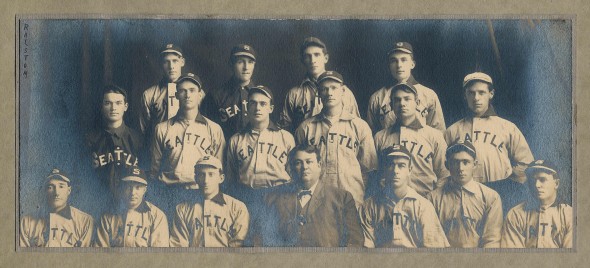

Still, Dugdale must have seen more opportunity in Seattle than he did in the Klondike because he signed on as grip man on the James Street cable car line. With his earnings, he speculated in real estate — successfully, as it turned out — and got back into baseball by establishing his own team, the aptly named Klondikers, who played their games, many for charity, at YMCA Park, on James Street between 12th and 14th avenues.

The Klondikers opened against Tacoma May 18, 1898, Dugdale turning the affair into a city-wide event. The Seattle newcomer organized a parade through downtown streets featuring players from both clubs in their uniforms, led by a marching band. The parade wound through Seattle for about an hour before ending at the YMCA ballpark, after which the teams were given 30 minutes to warm up. A crowd of 425 fans watched the Klondikers take an early 1-0 lead before losing by a score of 14-6.

By the time of that game, Seattle had already had a decade-long flirt with “professional” baseball. The first edition of the Pacific Northwest League launched in 1890 (included Seattle, Portland, Spokane and Tacoma), folded after the 1892 season, returned for 1896, and folded again.

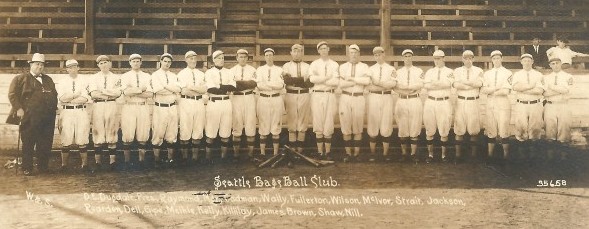

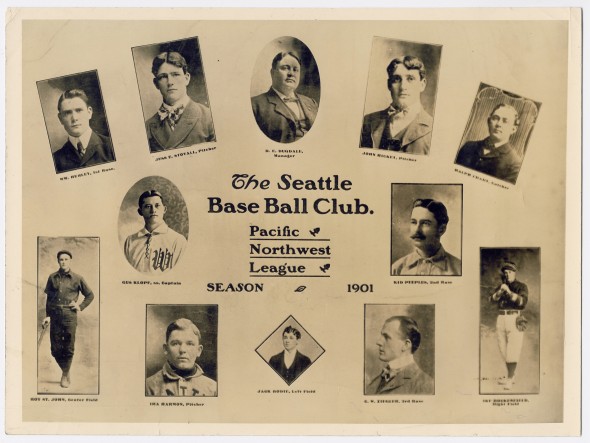

The Klondikers went out of business shortly before the scheduled end of the 1898 season, leaving Seattle without a club until 1901 when Dugdale helped form a second Pacific Northwest League, which included his Clamdiggers (1901-02), Portland, Tacoma and Spokane.

In December of 1902, the owners of an independent California league, headed by Henry Harris of San Francisco, announced the formation of the Pacific Coast League.

Harris hoped to lure Dugdales Chinooks (as well as the Portland franchise) into the PCL, but Dugdale snubbed the offer. Harris pulled an end run and located other owners for a new Seattle franchise, ultimately nicknamed the Siwashes. Suddenly, Dugdale had competition for fans and players, and a battle ensued, players jumping from one league to another (some were reportedly thrown in jail for breach of contract).

During this brief era of contract-jumping chaos, Dugdale became embroiled in a famous row with one of his players, Willie Hogg. Early in the 1903 season, another Dugdale operative, Ed Hurlburt, jumped to the PCL, prompting Dugdale to take him to court. By mid-June, Hogg desired to join Hurlburt in the PCL and asked Dugdale for his release.

Loathing contract jumpers, Dugdale refused Hoggs request. According to the Seattle Times, Hogg became abusive and threatened Dugdale, who mounted a defense. Wrote the Times: ”Hogg was put out of commission with a straight poke to the jaw that would have done credit to any knight of the ring.”

Sufficiently provoked, Dugdale apparently never hesitated to display his dander. Once, he got into a brawl with Gus Klopf, captain of the Spokane club who had previously played under Dugdale (1901-02), in a Seattle cigar store. Dugdale floored Klopf twice.

Dugdale would not win his battle with the PCL. When the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues admitted the PCL into its membership in 1904, Dugdale sold the Chinooks and moved to Portland to manage that city’s PCL entry, the Browns. Dugdale stayed in Portland only one year.

Back in Seattle after the 1904 season, Dugdale involved himself in a number of baseball projects, including his sponsorship of a 20-team semi-pro league in western Washington.

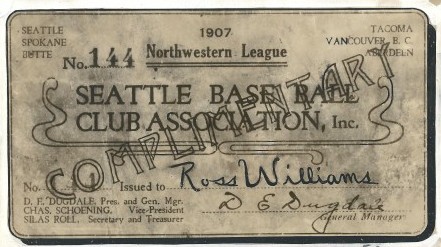

In 1906, travel complications created by the San Francisco earthquake forced the PCL to abandon Seattle. Dugdale, who worked primarily on his real estate portfolio in 1905, stepped into the void, claiming territorial rights, and affiliated his franchise – he retained the nickname Siwashes – as a new member of the Northwestern League, which, for 1907, had clubs in Aberdeen (Black Cats), Tacoma (Tigers), Butte (Miners), Spokane (Indians) and Vancouver (Horse Doctors).

Also that year, Dugdale commenced construction on his first baseball facility, Yesler Way Park, a band box located at 12th Avenue and Yesler Way that cost him $10,000. The new ballpark became one of two significant Seattle construction projects that year: The Pike Place Market also opened in 1907.

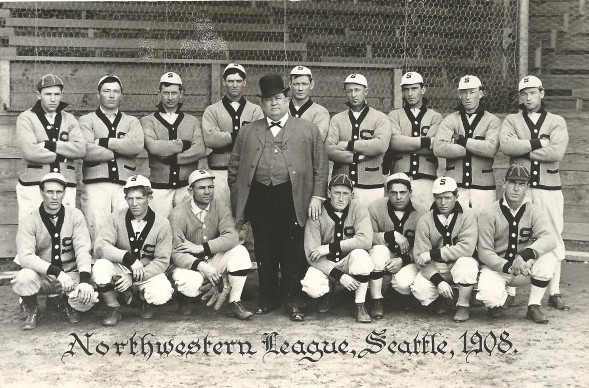

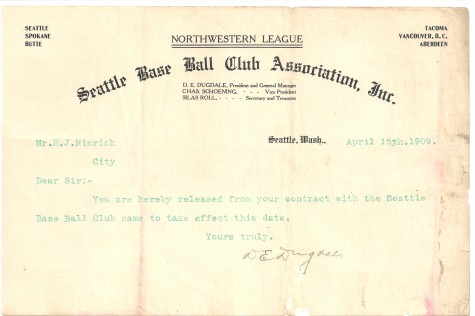

Dugdale last managed a Seattle franchise in 1908 when the Siwashes finished last (65-87). Still the owner and general manager, Dugdale’s Siwashes morphed into the Turks in 1909 (won the league pennant under manager Mike Lynch), and in 1910 a fan contest produced another new nickname for the franchise, the Giants.

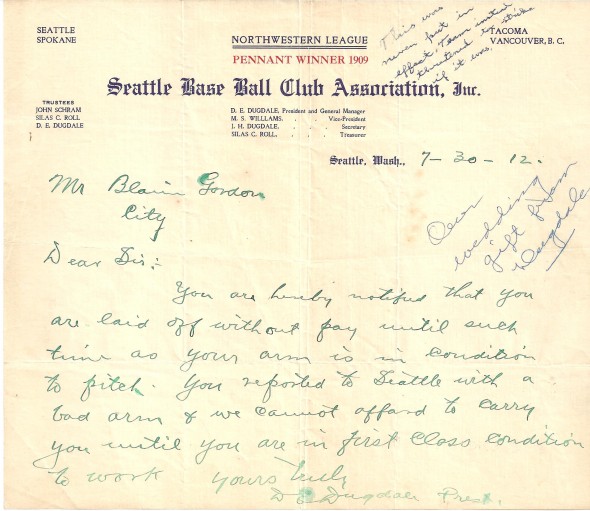

After finishing last in 1910 (61-99) and third in 1911 (90-77), Dugdale revamped his roster for 1912, most notably adding 20-year-old pitcher Bill James. After a slow start (last place through the end of May), Dugdale fired manager Jack Barry and hired Tealy Raymond to take his place. Under Raymond’s guidance and James’ outstanding pitching (he won 26 games), the Giants rallied to capture one of the most remarkable pennant races in the region’s baseball history — one that attracted numerous late-season throngs to 6,000-seat Yesler Way Park.

Partly as a result of fan response to the Giants at the end of the 1912 season, in part because of pressure to sell his valuable Yesler Way property to Seattle developers, Dugdale began designing a new ballpark that he hoped would be the finest on the West Coast. Dugdale’s problem: finding the right location. The solution: a man named Gene Way.

A former Seattle city councilman and real estate broker, Way owned a piece of ground at the intersection of Rainier Avenue and McClellan Street in the Rainier Valley that had literally once served as the local fishing grounds (before engineers re-jiggered the topography to drain the water that ran off Beacon Hill and washed in from the tide flats).

Dugdale liked the property, bought it, and began construction in early 1913 (Philadelphia A’s manager Connie Mack made some design suggestions). The Giants moved into $35,000 Dugdale Park, the first baseball facility on the West Coast to feature double-decked stands, late in the 1913 season.

Dugdale remained the owner of the Giants through 1918 (the Northwestern League became the Pacific Coast International League for the 1918 season). While his teams had won pennants in 1909, 1912 and 1915, owning a baseball club had become a financial liability (the Los Angeles Times reported in 1918 that Dugdales clubs had lost money three years in a row).

Dugdale’s final teams struggled to attract fans because Dugdale had trouble signing quality players with World War I intensifying (they were serving in the military).

On July 7, 1918, the Pacific Coast International League suspended operations due to the war.

Dugdale saw little future in professional baseball locally after that, and sold his majority interest in the Giants in January of 1919 to James Brewster, a cigar store magnate, for $60,000.

After joining the PCL, the Giants became the Rainiers (1919-21), then the Indians (1922-37), and the Rainiers again (1938).

Dugdale retained ownership of his namesake park until 1928, when he sold it to Indians owner Bill Klepper (Dugdale Field served as the Indians home until a July 4, 1932 fire left it in ruins, forcing the team to relocate to 9,000-seat Civic Field.)

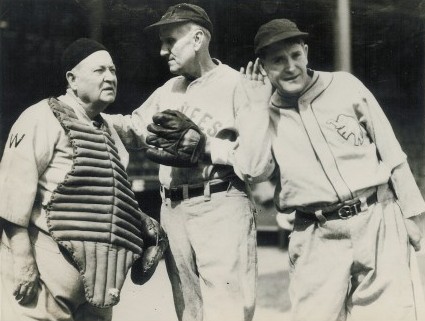

Dugdale had been a mostly popular owner with fans (he enjoyed chatting up bleacherites) and a respected one in the eyes of his peers, who frequently praised his commitment to the bottom line.

Not all of his employees appreciated that. After Dugdale fired Jack Barry as his manager early in the 1912 season, Barry told The Sporting News, “Cut down expenses is his hit-and-run sign.”

Wrote the Times: ”The passing of Dug marks an epoch in the baseball history of the Northwest . . . It is only by practicing rigid economy that he has managed to give Seattle continuous baseball.”

Dugdale never strayed far from sports after leaving professional baseball. He helped organize the amateur Seattle City Baseball League (served as president in 1931), frequently attended high school football games, track meets and wrestling matches, and showed up at most local boxing events (when The Meadows, a horse racing track at what is now the south end of Boeing Field, was in operation, Dugdale enjoyed betting the ponies. And he was among the first patrons at Longacres, which opened in 1933).

Dugdale wanted to take up golf, but couldn’t because of his weight. On Aug. 10, 1919, he quipped to the Times: ”When I could see the ball, I couldn’t reach it. And when I could reach the ball, I couldn’t see it.”

During his post-baseball years, Dugdale purchased property in Hayden Lake, ID., and became a prosperous apple grower.

He also involved himself in politics as a member of the Democratic Party, spending some time in the state legislature as a representative of the 34th District (Dugdale was once nominated to run for Seattle sheriff, but declined).

In Dugdale’s later years, most Seattleites considered him something of a gray eminence. After he received an award from his hometown of Peoria, IL., a man identified as Sergeant of Detectives Tennant, sent Dugdale a telegram.

It said, “Dugdale has a natural-born managerial genius. He knows how to manage people and baseball players. He’s made money where others have failed. He knows public wishes and respects them, and he’s on the square.”

As far as can be determined, Dugdale had only one smirch on his record (other than poking players on the jaw): On March 25, 1909, he and White Sox owner Charley Comiskey were arrested at Goldies bar at 604 Second Avenue shortly after 1 a.m. They were there — illegally, after closing hours — celebrating the completion of the arrangements for the White Sox to play several exhibition games in the Seattle area. Both men were released on $100 bail.

Following the death of his wife Mary in October 1933, Dugdale moved in with his sister, Elizabeth, at 4219 Beach Drive, and lived with her the last six months of his life.

Early in the evening of March 9, 1934, as a City Light truck cruised up Fourth Avenue South en route to downtown Seattle, its driver spotted what he later described as an older man approach the curb to cross the street a short distance ahead.

The driver, City Light lineman A.A. Peterson, slowed to allow the man to cross, but when the man took a step back the driver resumed his normal speed. Peterson later testified that he was surprised when the man stepped off the curb again and began to make his way to the other side of the street.

Peterson didn’t have enough time to react, and the truck struck the pedestrian.

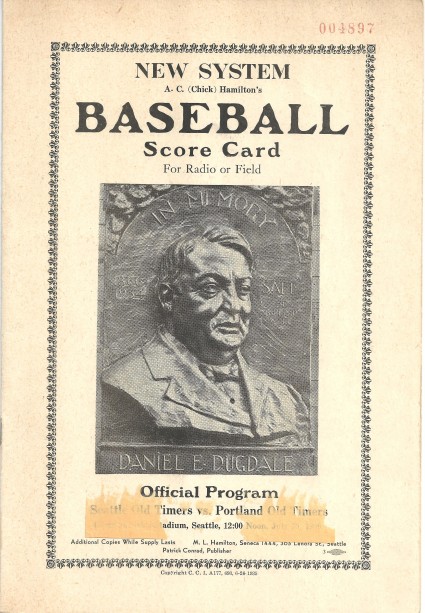

Medics rushed Dugdale to Providence Hospital, but he died three hours after admittance. Daniel Edward Dugdale, the “Father of Seattle Baseball,” was 69. He left an estate appraised at $7,000.

(Peterson was subsequently charged with manslaughter, but that was dismissed in January of 1935 for lack of sufficient evidence to prosecute.)

Upon Dugdale’s death, Seattle Times sports editor George Varnell wrote, ”The name of Daniel E. Dugdale has on this Pacific Coast been synonymous with all the better things that go with professional baseball. His word in a baseball deal was as good as his bond . . . He was a nobleman among his fellows.

“He was ’Dug’ to the multitude of his friends and acquaintances. Baseball was his life and in recent years he devoted his valuable experience and ability to the upbuilding of the lesser light of baseball, the semi-pros.

“But whether it was league ball, semi-pro, amateur or sandlot baseball for the kids, Dugdale always stood ready to put his shoulder to the wheel. And always it was there. Baseball was his first love, and his sudden and untimely death robs the Northwest of its greatest individual figure in the national game.”

Hundreds attended Dugdales funeral at St. James Cathedral (honorary pallbearers included Indians broadcaster Leo Lassen and Post-Intelligencer columnist Royal Brougham), and he was buried at Calvary Cemetery near the University of Washington.

On June 7, 1934, the Seattle Indians held “Dugdale Night,” at Civic Field, and the promotion, featuring music, a parade of American Legion drum and bugle corps, clown acts and speeches, attracted the largest crowd of the season (4,500).

None of the speakers bothered to speculate on how professional baseball in Seattle might have evolved had Daniel Dugdale not come west to seek his fortune in gold.

Check out David Eskenazi’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

7 Comments

It is fascinating to read the history of sports in Seattle. David, you write real good! Seriously, thanks!!! My mother’s parents talked of him attending their wedding. My mom says his wedding gift is in some box somewhere. Having just moved her into an assisted living place, I am not opening any more boxes for awhile. hehe

It is fascinating to read the history of sports in Seattle. David, you write real good! Seriously, thanks!!! My mother’s parents talked of him attending their wedding. My mom says his wedding gift is in some box somewhere. Having just moved her into an assisted living place, I am not opening any more boxes for awhile. hehe

correction on my comment…My mother just emailed me about your article. She told me her grandparents went to dinner with Mr and Mrs D often. Mr D gave mom a rosary from his trip to Rome. Her grandparents spent a few years living in Skagway during the goldrush.

correction on my comment…My mother just emailed me about your article. She told me her grandparents went to dinner with Mr and Mrs D often. Mr D gave mom a rosary from his trip to Rome. Her grandparents spent a few years living in Skagway during the goldrush.

Yup, what they’re doing in batting practice is carrying over! to … uh oh… a batting practice pitcher in fly-away air. Pitcher booed by the home team crowd in the 2nd?! Rhymes with Bobby Ayala?

Wedgie was gifted with something to hang his corporate positive-spin upon: a venue to make his guys look good. The FO still has fielded a terrible team, spent their shrinking budget badly, and gone into deep seclusion.

i thought the 95 mariners were a good memory? the only good memory.

jay buhner is the mariners’ reggie jackson. except nobody outside the sound gives a damn what he says.