By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

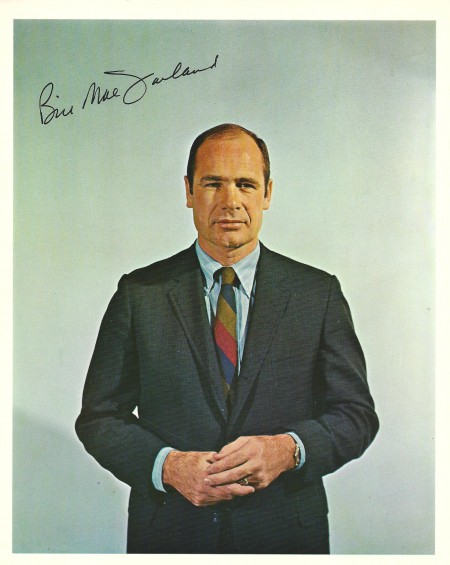

Of the countless thousands of professional athletes who have meandered through the Pacific Northwest, none had a more varied or intriguing career than Bill MacFarland, whose Aug. 12 passing in Scottsdale, AZ., came and went with far too little notice or acknowledgment.

Leading off MacFarland’s catalog of intrigues: he is the only professional athlete (at least that we know of) in Seattle history who received a law degree while earning a living as an active player.

During a hockey career that began in the early 1950s and didn’t start to ebb until the mid-1990s, MacFarland also coached, worked as a general manager, served terms as president and CEO of two leagues, and owned and operated franchises in sports other than his primary one.

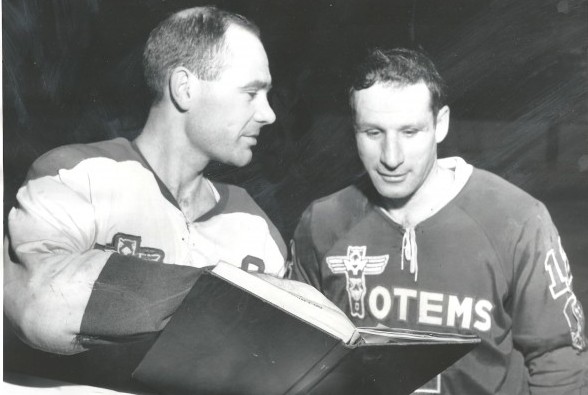

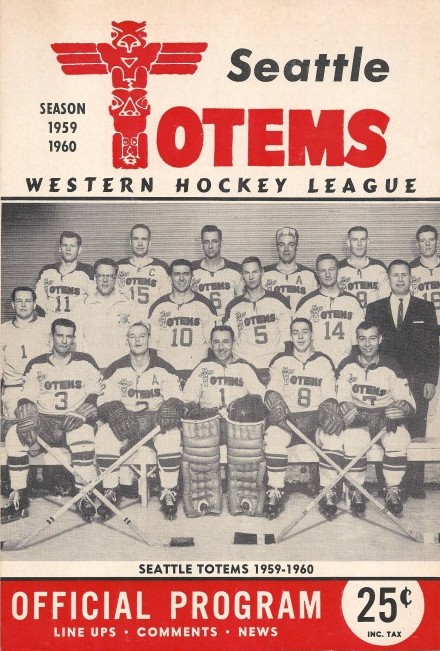

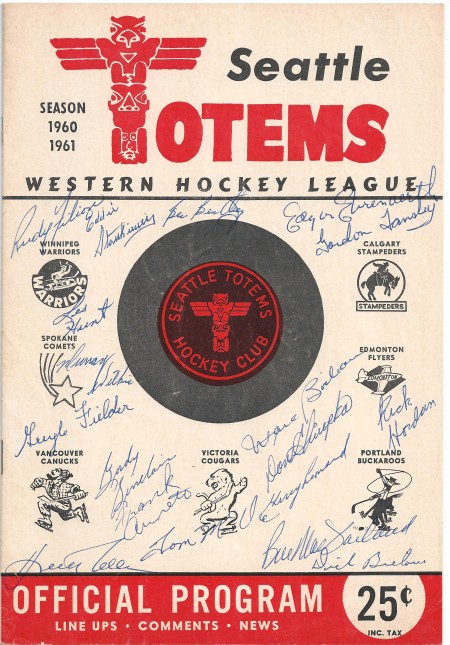

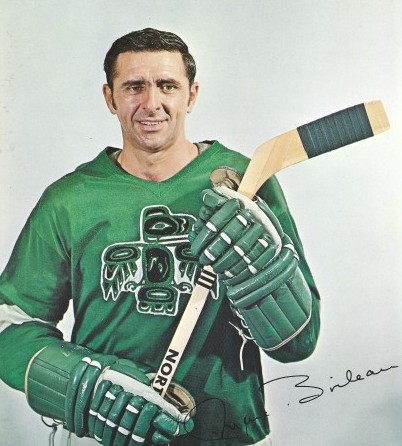

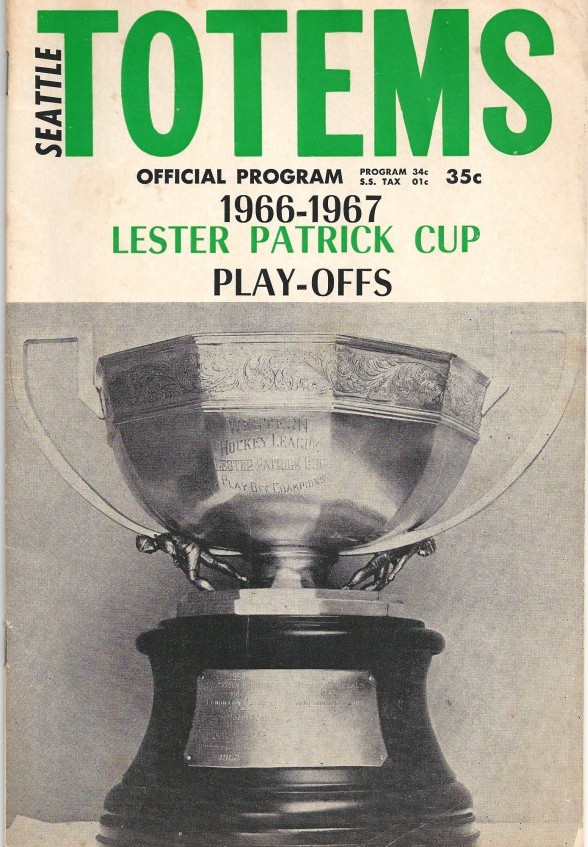

Long-toothed Northwest sports fans will recall MacFarland most for the 10-plus years he toiled for the old Seattle Totems (alongside the likes of Guyle Fielder and Rudy Filion), his four seasons as the team’s head coach, and the impact he had on three Western Hockey League championships, one as a player (1958-59), and two as a coach (1966-67, 1967-68). In all, the Totems played for the WHL title five times during MacFarland’s association with them.

During the era of the Totems (1958-75), MacFarland was the only Seattle player not named Guyle Fielder to lead the WHL in scoring and win a Most Valuable Player award (1961-62).

None of that, much less his long Seattle residency, would have occurred if MacFarland hadn’t set his sights on becoming a lawyer after graduating from the University of Michigan.

A Toronto native (born April 4, 1932), MacFarland took up hockey on a junior level with his hometown Marlboros (founded 1903) in the early 1950s. Instead of signing with a high-level amateur team or turning professional after completing his junior eligibility, MacFarland took the-then unusual step of enrolling at Michigan in 1952 – unusual in the sense that college hockey was not considered a natural steppingstone for anyone with professional aspirations. But MacFarland had ambitions far beyond the skating rink.

MacFarland played three seasons for the Wolverines and captained Michigan outfits that won back-to-back NCAA tournaments in the 1954-55 and 1955-56 seasons. Named to the NCAA Frozen Four All-Tournament team in 1955, MacFarland left Michigan with three All-America citations (MacFarland entered the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor in 2009).

Drafted by the Detroit Red Wings in 1956, MacFarland attended two training camps and saw action in a few exhibition games, but couldn’t crack Detroit’s roster (in those days the NHL had only six teams) and was sent to the WHL’s Edmonton Flyers (1940-63). After one year in Edmonton, MacFarland requested a trade to the Seattle Americans, and the Red Wings obliged.

With the Americans, MacFarland filled a roster spot that had been vacated by Fielder, who made the Red Wings coming out of training camp in 1957. Fielder, of course, ultimately returned to the Totems, necessitating MacFarland’s switch from center to left wing.

MacFarland’s priority was not so much playing for the Americans as it was enrolling in the University of Washington School of Law.

“It was either 30-below (in Edmonton) or be a Husky,” McFarland told an interviewer. “I knew the University of Washington had a good academic reputation.”

While working on his law degree, MacFarland developed into one of the premier players in the WHL — one who could knock the puck in the net with regularity and handle himself when play got rough, which it often did.

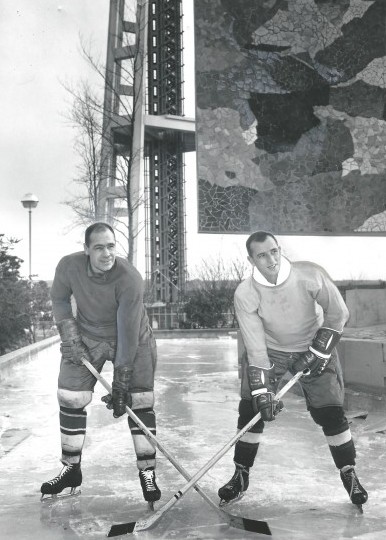

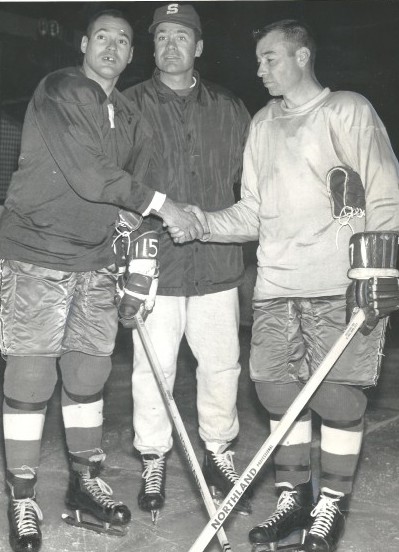

As a rookie in 1957-58, MacFarland recorded 31 regular-season goals and added 28 assists, a total of 57 points in 70 games. In 1958-59, the season in which the Americans became the Totems, MacFarland tallied 35 regular-season goals (teamed with Filion and Marc Boileau on a line that became the highest-scoring unit in the league) and added 17 playoff points as the Totems won their first WHL championship.

Playing in 60 or more games nine times in 10 years, MacFarland notched 30 or more goals seven times and 30 or more assists eight times. He made first-team All-WHL in 1962 and second team in 1960, 1964 and 1966.

MacFarland produced his best year in 1962 when he scored a league-high 46 goals (also had 35 assists and tallied three hat tricks) and won the Hiram Walker Trophy as the league’s Most Valuable Player.

An article in the January, 1974 issue of Seattle Totems Hockey Magazine quoted an unidentified teammate as saying, ”He (MacFarland) was a complete hockey player: he had size (6-1, 190), skating ability and intelligence. He could pass the puck, he was a great goal scorer, and he was tough. Not a bad checker, either. So what else is there? Nowadays, major league teams would be falling all over themselves to pay him a fortune.”

Midway through his playing career (1964), MacFarland passed the Washington state bar exam and went on to immerse himself in players rights issues. He helped establish a pension fund for retired WHL players, the first of its kind in minor league hockey.

MacFarland also continued to play All-Star-caliber hockey, to the astonishment of many who wondered why he wanted to give – and get – fat lips when he could have occupied a posh office as a lawyer at considerably more money than minor league hockey players made in those days.

The answer, as MacFarland often said: ”I loved to play.” He also liked to enforce, in hockey parlance. MacFarland threw punches so effectively that teammates nicknamed him “Packy” after a Chicago welterweight of the day. MacFarland got the moniker after decking a skater during an entertaining brawl in Vancouver.

Wrote the Seattle Post-Intelligencer after MacFarland received his law degree: ”He simply has a cerebral side, too. The combination of hockey arena and courtroom acumen make him the most erudite hockey man to come through the Northwest.”

Initiating groans in readers, Seattle sports scribes frequently asked, ”Who is this guy with a stick in one hand and legal brief in the other? If they hit him, will he sue for damages?”

Once, during a playoff series in San Francisco, MacFarland got shoved through an open arena gate and banged his head against a parked Zamboni machine. In a retaliation attempt against the player responsible for his noggin conk, MacFarland suffered a split lip. When he sought medical treatment, an attending doctor asked, “Didn’t I read somewhere that you passed the bar exam? If so, then why are you doing this?”

MacFarland retired as an active player following the 1965-66 season after scoring 299 regular-season goals and 643 points, totals that ranked third all time (behind Fielder and Filion) in Americans/Totems history. He added another 25 goals, 43 assists and 68 points in playoff contests, giving him 324 goals in 688 career games for Seattle teams. A dislocated knee plus six broken teeth, among other occupational hazards, hastened his departure from the ice at the age of 34.

MacFarland then moved behind the Totems bench, assuming coaching duties from Bobby Kromm, a longtime player and coach with Trail and Nelson in the senior amateur Western International Junior Hockey League. At the same time, MacFarland went to work on a part-time basis for team owner Vince Abbey’s law firm.

The first Totems team MacFarland coached started dubiously, winning just four times in 17 games. But the Totems rebounded to finish 39-26 and in second place. In the WHL playoffs, the Totems beat California 4-2 in a six-game series and then swept Vancouver to claim the Lester Patrick Trophy.

MacFarland and the Totems also won the Lester Patrick Trophy in MacFarland’s second season, and that title featured one of the most spectacular comebacks in Seattle sports history.

The 1968 WHL playoffs began with Seattle facing Phoenix in the opening round. The Totems outscored the Roadrunners 16-7 and recorded a four-game sweep.

In the finals against the arch-rival Portland Buckaroos, the Totems picked up a win in Game 1 but fell behind 6-2 after two periods during Game 2 in Seattle. The Totems received two goals in the first minute and a half of the third, and another about halfway through the period to cut the Buckaroos lead to 6-5.

The Totems thought they scored the tying goal late in the period, but it was waved off due to a high stick. With just over a minute to go, Seattle yanked its goaltender, and scored with 19 seconds left to tie it up.

In overtime, Fielder got the game winner in what announcer Bill Schonley called the “greatest comeback in Seattle hockey history.” The Totems went on to win the series in five games, finishing with an 8-1 record in the playoffs (MacFarland’s first two playoff teams went a combined 16-3).

What no one knew then was that the Totems had won the last playoff series they would ever win.

MacFarland coached two more seasons and could have taken the same career path as two predecessors, Keith Allen and Kromm.

Allen spent eight seasons coaching the Americans/Totems (1957-65), and then went on to coach the Philadelphia Flyers. After the 1968-69 season, Allen became Philadelphia’s general manager and built the Broad Street Bullies into a two-time Stanley Cup champion.

Kromm, who spent just one year as the Totems coach (1965-66), moved on to the Central Hockey League’s Dallas Blackhawks. He coached there for eight years, winning three league titles. Kromm subsequently coached the Detroit Red Wings for three seasons.

MacFarland, who finished with a 137-121-33 record, had no interest in spending any more time behind a hockey bench.

“I got bored with coaching,” MacFarland said. “The farther I got away from the ice surface, the less enjoyable it was.”

MacFarland practiced law for a year in Seattle and, from 1972-74, served as president of the WHL. His most notable accomplishment as league president: he arranged two exhibition series between WHL clubs and Russia’s world championship team.

The Russians predictably dominated, winning seven of the eight games contested, but the lone victory, by the Totems Jan. 5, 1974 at the Seattle Coliseum, provided Seattle with one of its top hockey moments.

After the demise of the WHL (1974) and the Totems franchise a year later (a folding prompted by the NHL awarding an expansion franchise to Seattle), MacFarland relocated to Phoenix, where he first became one of the owners of the Phoenix Roadrunners, and later president and legal counsel, of the World Hockey Association (1975-77.)

MacFarland finally separated himself from professional hockey when the National Hockey League merged with the WHA in early 1979.

MacFarland’s most notable post-hockey involvement in the sport occurred in the early 1990s, and represented one of two significant efforts that nearly resulted in a National Hockey League franchise landing in Seattle.

On June 12, 1974, the NHL announced that a Seattle group headed by Abbey, owner of the Totems, had been awarded an expansion team to begin play in the 1976-77 season. As a condition, the NHL mandated that Abbey (and his partners) make a $180,000 deposit on the franchise by the end of 1975. The total franchise fee would amount to $6 million.

In addition, the NHL declared that Abbey had to repurchase the shares in the Totems held by the Vancouver Canucks, who were using the minor-league Totems as a farm club, and had lent the Totems money to be used as operating capital.

The NHL’s expansion announcement also included a franchise for Denver. With the loss of two of its major markets, the WHL announced that it would fold. The Totems joined the Central Hockey League for 1974-75, but were goners after that season.

Abbey missed several NHL-imposed deadlines while scrambling to secure financing, and with each miss the NHL threatened to pull the franchise, claiming that it had a number of other suitors in the wings.

During this time, Abbey passed on an opportunity to purchase a WHA team for $2 million, and also missed a chance to acquire an existing franchise when the Pittsburgh Penguins were sold in a bankruptcy proceeding for $4.4 million in June 1975.

After the Totems folded, the NHL pulled the expansion franchise from Seattle, leaving the city without hockey for the first time in two decades (Denver also lost its franchise). Abbey filed suit against the NHL and the Canucks for anti-trust violations that he alleged prevented him from acquiring a team; it was finally settled in favor of the NHL in 1986, when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals threw out all claims by Abbey.

That seemed to end Seattle’s chances of ever receiving another franchise until the NHL announced a new round of expansion set to take place for the 1992-93 season. Two groups in Seattle surfaced as ownership candidates, one headed by Bill Ackerley, son of Sonics owner Barry Ackerley, the other by Microsoft executive Chris Larson, with MacFarland serving as an advisor. Ultimately, the two camps joined forces.

In the fall of 1990, Larson and MacFarland met with the NHL’s Board of Directors, and the hockey suits went gaga at the prospect of welcoming a Microsoft millionaire into the flock. Then, on Dec. 5, MacFarland, Larson, Barry Ackerley and Bill Lear, an Ackerley financial advisor, traveled to West Palm Beach, FL., to meet the NHL’s Board of Governors at the Breakers Hotel.

Considered a lock to land a franchise, the Seattle contingent did not even receive a full hearing, that because Barry Ackerley pulled out without acknowledging Larson or McFarland, or giving any reason.

“He (Ackerley) double-crossed us,” MacFarland told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. ”He admitted it.”

Bill Ackerley also admitted – and denied – a lot of things in the aftermath of one of the major Mr. Magoo mixup/mishaps in Seattle’s pro sports history.

Although the NHL had set a $50 million minimum price tag for an expansion franchise, Larson figured that a $35 million offer would get him in the door and a chance to negotiate.

What neither Larson nor MacFarland knew was that while they had gone to Florida to file an application for a team, Acklerley actually had gone there to withraw it. Incredibly, none of this came up when the Seattle group convened in strategy sessions prior to meeting with the NHL.

MacFarland, Ackerley and Lear had dinner the night before the meeting and the subject of the application didn’t come up. Joined by Larson, they all had breakfast on the morning of the meeting. Ackerley never said a word about pulling the application.

“I mean, we were there thinking we were going to be working with these people to bring the NHL to Seattle,” MacFarland told the Post-Intelligencer.

MacFarland later told the News Tribune (Tacoma) that the four of them were sitting in a room waiting to speak to NHL execs when then-NHL president John Ziegler stuck his head in and informed them they were next on the docket.

At that point, MacFarland recalled, Ackerley asked his allies if he could address NHL officials by himself before the group as a whole met league officials.

“It seemed a little weird, MacFarland, but what the heck. We said, ‘No problem.'”

When Ackerley confronted NHL owners, he formally withdrew the franchise application while MacFarland and Larson waited in the other room, oblivious to what Ackerley had done. Ackerley never did – at least adequately – explain himself. He simply departed the hotel via a side door and flew back to Seattle.

A few minutes after Ackerley vamoosed, NHL official Gil Stein informed Larson and MacFarland that the expansion application had been pulled and that Ackerley had left the building.

“We were floored; we couldn’t believe it,” MacFarland told the P-I. ”Why were we here? How could they sit with us and not tell us what they were going to do?”

No one ever received a satisfactory answer. Bill Ackerley later told the News Tribune that, ”We felt the money wasn’t there, and we didn’t want to damage our name and reputation with the NHL by offering up something that would be unacceptable to them. We went to Florida with the intent of pulling the application. We just felt it wasn’t going to happen financially.”

If so, why didn’t Ackerley inform Larson and MacFarland of his intention to pull the franchise at dinner or breakfast?

Said Ackerley: “It just never came up.”

And why were Larson and MacFarland in Florida at all if Ackerley didn’t think Larson had enough money to acquire a franchise? Larson two years later would become the second-largest percentage owner of the Mariners, behind Hiroshi Yamauchi of Japan, who helped purchase the MLB team from Jeff Smulyan for $200 million.

Ackerley never offered a plausible explanation. He claimed that he had been unaware that Larson was prepared to spend at least $35 million, and $50 million if necessary. He said he was under the impression that Larson only had $10 million to invest. He said he was surprised that Larson and MacFarland traveled to Florida in the first place.

Ackerley sort of took responsibility, saying, “It was my fault, and I’m sorry for the way it happened, and there was no intent to embarrass Chris Larson or anybody, and there’s a lot I wish I would have done differently.” In the end, Ackerley blamed the loss of an NHL franchise on a miscommunication (“For want of a nail the shoe was lost . . . ).

MacFarland always believed that Barry Ackerley never wanted an NHL franchise that would have competed with the Sonics team he owned in the same building (Coliseum, later KeyArena), and that he only wanted to control the application process to ensure that. Half a decade later, MacFarland’s opinion became reality when the Seattle Coliseum renovation into KeyArena provided no adequate configuration — just 10,000 unrestricted view seats — for NHL hockey.

MacFarland had little involvement in professional sports after that botched episode. In 1993, he purchased the expansion Las Vegas Sting (1994-95) of the Arena Football League. And for a couple of years, he owned the Continental Indoor Soccer League’s (1993-97) Las Vegas Dustdevils (won the league championship in 1994).

Mainly, MacFarland did what he did best: he lawyered. He spent 17 years with Sterling International, a company that recruited high-level executives for multinational Asian businesses.

In semi-retirement, MacFarland did some consulting work, and in retirement, he played a little golf, toured Europe and occasionally got together with some of his old Totems teammates, including fellow Arizona denizen Guyle Fielder, to hob nob.

MacFarland never played a game in the National Hockey League. But he made it big everywhere else he elected to go, dying at the age of 79 after a life well lived.

———————————————

Check out David Eskenazis Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

5 Comments

Why don’t you write about Larry Zeidel. He was my favorite player as a kid. I still have a puck he knocked out of the rink. He led the leage in penalty minutes more than once. He was the teams “Bad Boy”.

We’ll look into that, thanks Craig.

Great article!

Much of that time frame represented my childhood and those Totems were heros to me. Several lived in my apartment complex in what is now Shoreline. Played hockey with some of there kids and went to their hockey camps.

Thanks again.

A wonderful and proper tribute to one of Seattle hockey’s greatest figures. It’s because of people like him I’m still a hockey fan today. Thank you, David.

I am a 75 year old Canadian and a childhood neighbour and.friend of Bill MacFarland and his family. We lived on the same street in North Toronto prior to Bill heading out to the University of Michigan before he went to Seattle. Bill was four or five years older than me, his brother, John and his sister, Sandra so as a result he always”looked out” for us little kids. I never saw Bill again after he left Toronto but I was aware of his accomplishments. I became aware of his passing just today which of course has saddened me considerably. Thank you for your terrific article and pictures.