By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Every retrospective on the career of professional sports executive Marvin Milkes invariably starts with the fact that he was the only general manager the Seattle Pilots had (1969), that he served as the first GM of the Pilots successors, the Milwaukee Brewers (1970), and that he wound up becoming one of the few men in his business to preside over franchises in three sports: baseball, hockey and soccer.

During his athletic wanderings, Milkes made two moves he especially came to regret, the first occurring shortly after he became GM of the Pilots.

On Oct. 21, 1968, five months before the Pilots played their first game, Milkes purchased a one-time starter turned knuckleball reliever, Jim Bouton, from the New York Yankees. With that acquisition, Milkes unwittingly provided Bouton with the perfect environment in which to write Ball Four.

Boutons diary of the 1969 Pilots season not only changed — for the worse, according to men such as Milkes — how the media covered sports, it also saw fit to immortalize Milkes as the epitome of front-office deviousness. Wrote Bouton:

“As soon as a general manager says ‘Now I want to be honest with you’, check your wallet. It’s like Marvin Milkes telling you, ‘We’ve always had a nice relationship.’ The truth is general managers aren’t honest with their players, and they have no relationship with them except a business one.”

Milkess second career rue came just before the launch of the Pilots season when he traded injured rookie Lou Piniella, sending him to Kansas City on April 1, 1969, for John Gelnar and Steve Whitaker. Piniella, who became that seasons AL Rookie of the Year, provided Milkes with 17 years of anguish as he carved an All-Star-caliber career.

Milkes had many successes. Years before he goofed with Bouton and Piniella, he toiled as the assistant general manager and later as executive vice president of the expansion (1961) Los Angeles Angels. In those capacities, he aided GM Fred Haney in building the Angels organization from scratch, and was responsible for many of the initial player acquisitions.

By 1965, Milkes had also been appointed to oversee the Angels minor league system, which included the Triple A franchise in Seattle, and it was with the former Seattle Rainiers that Milkes became involved in what he liked to describe as my pet project.

From 1919-21, the Seattle franchise played as the Rainiers, and then as the Indians from 1922-37. After Rainier Brewery owner Emil Sick purchased the franchise from Bill Klepper, the team reverted to its original PCL moniker, the Rainiers.

The appellation stuck through the remainder of Sicks stewardship (1960) and through a subsequent ownership by the Boston Red Sox (1961-64), to whom Sick sold the franchise.

On April 1, 1965, the Red Sox, desiring to operate a Triple A franchise closer to Boston (specifically Toronto), sold the Rainiers to cowboy crooner Gene Autrys Los Angeles Angels, who had just renamed themselves the California Angels.

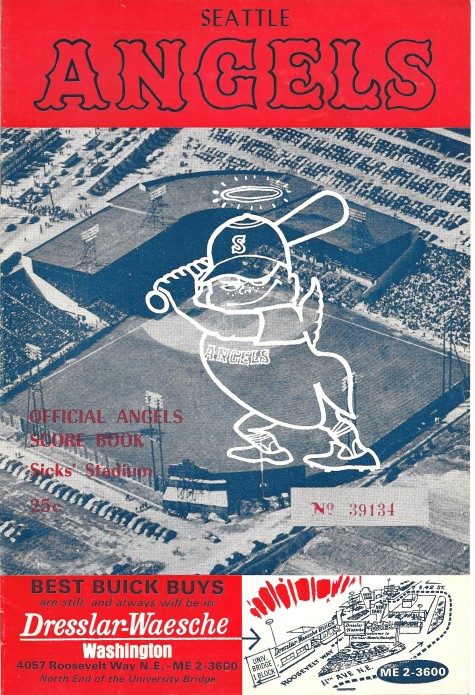

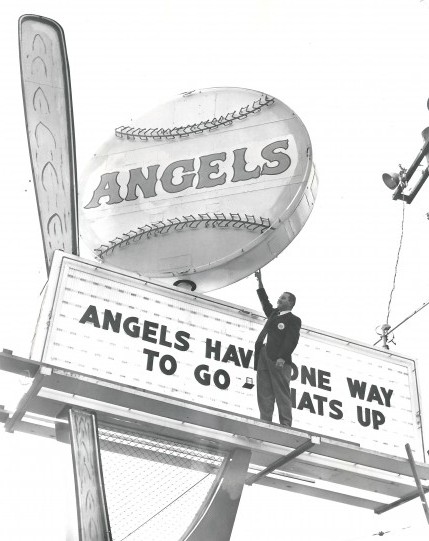

Upon completion of the purchase, the Angels shed the Rainiers nickname once and for all and rechristened the team the Seattle Angels. Haney placed Milkes in charge of supervising the operation.

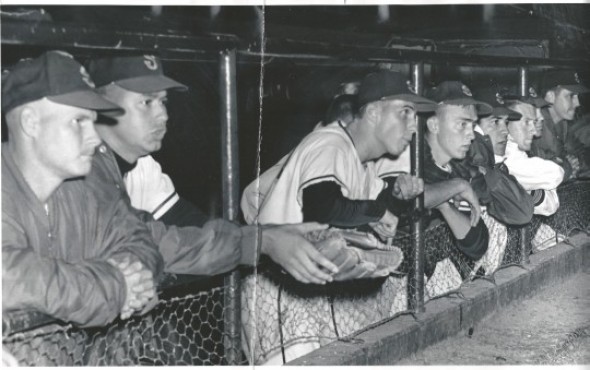

Unlike the historically popular Rainiers, the Seattle Angels didnt attract many fans. In those days, Seattle newspapers ran two or three stories a week speculating on Seattles chances of acquiring major league baseball and National Football League franchises, often suggesting Seattles move to the majors was imminent.

Perhaps Seattle sports fans felt they were above supporting minor league baseball anymore. Whatever the reason, the 1966 Angels, following a one-month spring training in Holtville, CA., played a majority of their 74 home games at Sicks with 1,000-2,000 fans on average rattling around the ballpark that after drawing just 3,111 for the home season opener on April 22 against Portland, and that despite the fact the Angels spent the season embroiled in a tight, entertaining race in the Pacific Coast Leagues Western Division.

(Despite the closeness of the race, neither the Seattle Times nor Post-Intelligencer saw fit to make much out of the Angels, consigning them nine days out of 10 to page 2 or 3 and routinely failing to update the PCL standings.)

At the end of April, the Angels stood 8-6 and in second place, a half game behind Hawaii. By the first of May, Seattle (22-19) had jumped into first, a half game ahead of Portland.

On June 1, the Angels were back in second, a half game behind the Beavers.

At the beginning of July, they were 41-32 and had a three-game lead over Spokane. The Angels increased their lead to five games over Vancouver by Aug. 1 (61-48).

When the regular season ended on Sept. 5, Seattle had won the Western Division with an 83-65 record and a six-game bulge over the Mounties. The division triumph set up a best-of-seven for the PCL championship against the Eastern Division champion Tulsa Oilers, who had briefly featured a 21-year-old left hander named Steve Carlton.

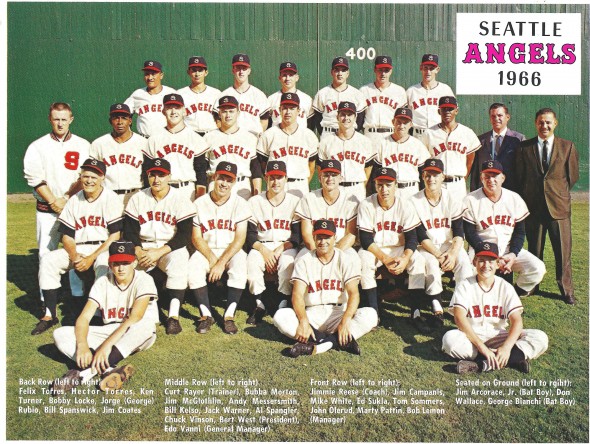

The Angels had an odd statistical look. None of the 20 pitchers on what swelled, through call ups, send downs, trades and injuries, into a 62-man roster by the end of the year came close to winning 20 games, or even 15. In fact, the staff leader won only 11. But 18 of the 20 won at least once and 15 won three or more.

Those 20 pitchers also collaborated to offset a general lack of pop from the offense by leading the PCL in ERA (3.34) and allowing the fewest average runs per game (3.66).

Only 10 of the 42 position players had as many as 300 at-bats and, of the 10, just two hit .300 or higher. Only five players hit more than 10 home runs and only one, Felix Torres, reached 20.

The team hit only 88 home runs in a 148-game schedule (seventh in the 12-team PCL) and batted .258 (sixth), despite several games like the one on July 30 against Portland, in which the Angels won 15-1 with 20 base hits.

Of the 62 players/pitchers, only nine were 30 or older. About half had some major league experience, and a few had spent quite a number of years in the show. Many of the 62 who started the season in Seattle departed by the time the PCL playoffs commenced, and many of the key contributors in the playoffs were in other organizations or the low minors when the season began.

It would have been impossible to gain any perspective on Seattle’s roster flux at the time, but it’s safe to say that if Marvin Milkes could look back on his “pet project” he would be more amazed than anyone at the cast he assembled, and how his handiwork ultimately played out.

One starting pitcher, 28-year-old Chuck Estrada, traded by Seattle to Tacoma two months into the season, was already an American League All-Star (1960).

Four others, Jim McGlothlin, (1967), Marty Pattin (1971), Andy Messersmith (1971, 74-76) and Tom Burgmeier (1980) would become major league All-Stars after departing Seattle.

The youngest Angel, 18-year-old shortstop Aurelio Rodriguez, would turn into an AL Gold Glove winner (1976). Messersmith would win two (1974-75) in the NL.

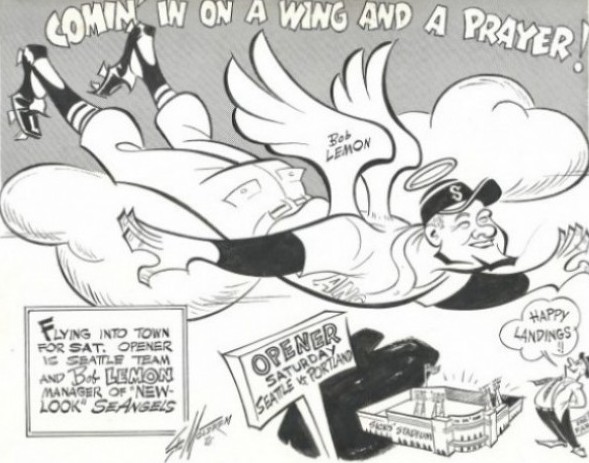

The skipper, Bob Lemon, who won a World Series ring as a player (Cleveland, 1948), would win another as a manager (1978, Yankees), and enter the Baseball Hall of Fame (1976).

Seattles pitching staff included (briefly) the 1962-63 National League leader in losses (Roger Craig, 24, 22), the Opening Day starter for the 1963 Pittsburgh Pirates (Earl Francis), a future key operative for the 1970 Big Red Machine (Jim McGlothlin), the 1967 AL saves leader (Minnie Rojas), a right-hander (Estrada) who had led the NL in both wins (18, 1960) and losses (17, 1962), the 1980 AL ERA champion (Rudy May, 2.47), and a future Seattle Pilot (Pattin).

The positional roster featured the starting shortstop for the 1962 St. Louis Cardinals (Julio Gotay), the starting left fielder for the 1962 Houston Colt 45s (Al Spangler), the future third baseman of the Detroit Tigers (Rodriguez), a future Seattle Pilot (Merritt Ranew), the son (Mike White) of a Seattle Rainiers star player and manager (Jo-Jo), the father (John Olerud Sr.) of a future Mariner (John Jr.), and the offspring (Jim Campanis) of a father (Al), who would one day shock baseball by trading his son.

The field roster further sported the first individual to play for both Canadian franchises, the Expos and Blue Jays (Hector Torres), a former roommate of Babe Ruths (Jimmie Reese), a former roommate of Roberto Clementes (Gotay), and a former roommate of Hank Aaron’s (Bubba Morton).

It had an active NBA player (Cotton Nash), one of baseballs most storied flakes (Jay Johnstone), the second man from the Bahamas to play in the majors (Tony Curry), and a player (Messersmith) whose name would, a decade later, become attached to one of the landmark legal rulings in baseball history.

The 1966 Angels included the only native of Slab Fork, W.VA. (Earl Francis) ever to pitch in the majors, pitcher Jack Warner and outfielder Jackie Warner, an off-season hairstylist (Bobby Locke), a future champion cutting horse breeder and trainer (Ranew), and a player who nearly got killed during a game (Ranew again).

The Angels also had one of only three men named Auerilio (Rodriguez) to ever play in the majors, a coach using an assumed name (Reese), and a part-time voodoo practitioner (Gotay).

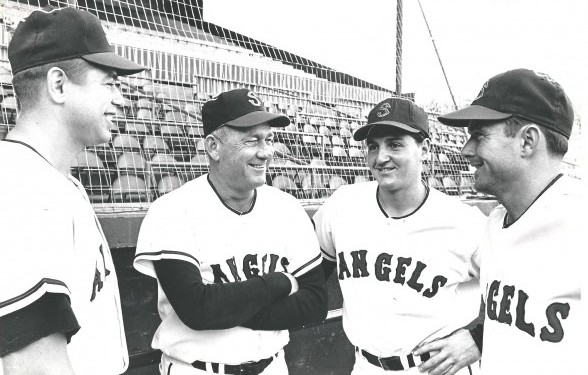

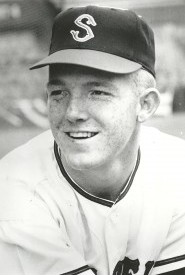

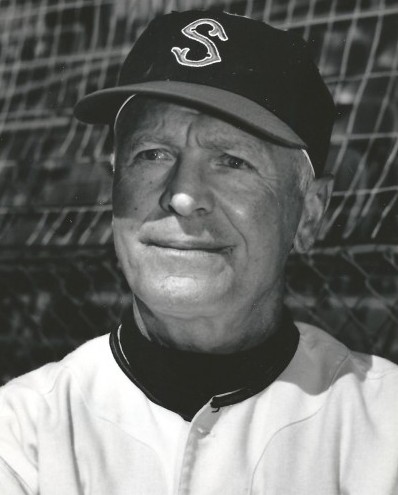

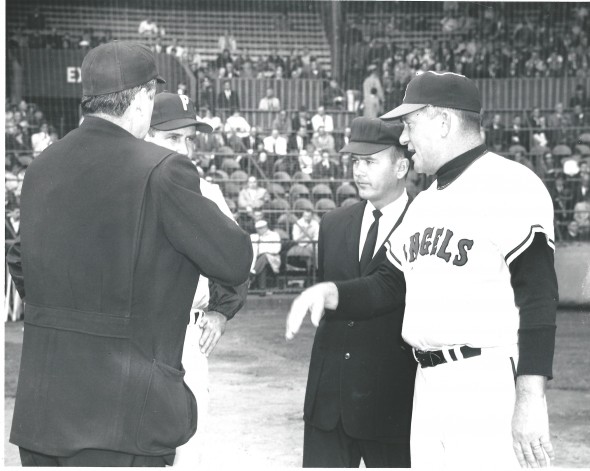

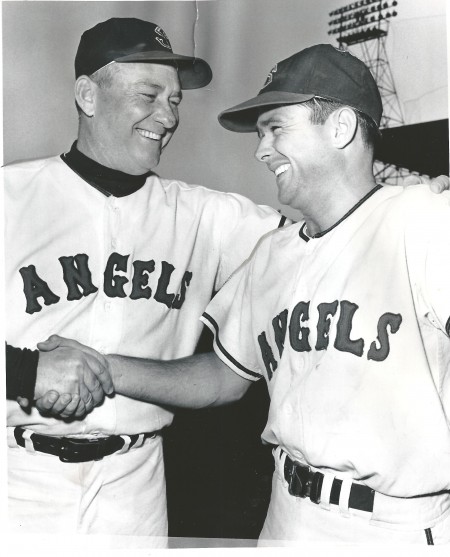

Lemon largely inherited this eclectic collection when, at the invitation of Milkes, he came to the Angels as their manager in 1965 after spending 1964 guiding the PCLs Hawaii Islanders.

The 46-year-old brought vast expertise, having played 18 seasons from 1938-58, including 15 in the majors (1941-42; 1946-58) and six in the minors (1938-42; 1958), losing three years to the military.

A sinker-ball specialist, Lemon had won 20 or more games seven times, made the AL All-Star team seven times in a nine-year span, and been a part of one of the most potent pitching staffs in history, alongside Bob Feller, Mike Garcia and Early Wynn.

Lemon had thrown a no-hitter against the Tigers, won a World Series ring (1948), and led the AL in victories three times, in complete games five times and in innings pitched four times.

With Edo Vanni, Seattle’s 1964 manager, having moved up to the general manager’s chair in the first year of Angels’ ownership, Lemons initial Seattle team went 79-69 and finished fourth in the Western Division. After managing the Angels for a second season, Lemon skippered Kansas City (1970-72), the Chicago White Sox (1977-78) and New York Yankees (1978-79, 1981-82), the latter club at a time when George Steinbrenner practically changed managers monthly.

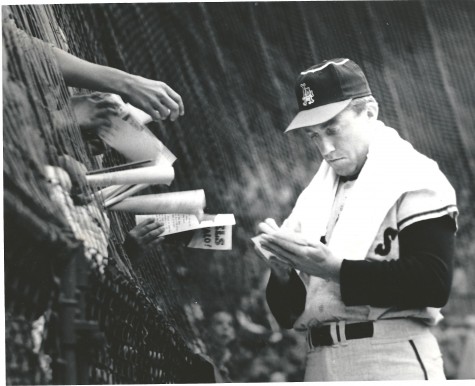

Jimmie Reese became one of Lemons first hires after Lemon accepted Milkes offer to manage the Angels. But Jimmie Reese wasnt his real name. He had been born Hyam Solomon, and his birth name had been variously given as Hymie Soloman, Herman Soloman, James Herman Soloman and James Hymie Solomon.

Whatever his true name, he changed it to Jimmie Reese and used it throughout his career in order to avoid the extreme prejudice against Jewish ballplayers of his era.

A second baseman, Reese played three years with the Yankees (1930-31) and Cardinals (1932). He roomed with Ruth in New York, although he liked to quip that he really roomed with Babe Ruths suitcase, Ruth being famous for his all-night soirees.

Although good enough to hit .278 in 232 major league games, Reese spent the majority of his career in the PCL, first as a batboy with the Los Angeles Angels in 1919.

Reese had a 15-year minor league career with the Angels, Oakland, San Diego and Spokane. Following World War II, he scouted for the Boston Braves, and coached and managed in San Diego (1948-61). A life-long bachelor, he lived only for baseball.

His managerial stint lasted only a year and a half, Reese resigning because, Im just not cut out to give a guy hell.

By the time Reese arrived in Seattle he had already become a legend for his wizardry with his self-made fungo bat. Reese had an uncanny ability to hit fungos anywhere he wanted. He sometimes even pitched batting practice with his fungo bat: hed stand at the pitchers rubber and consistently smack line drives over the middle of the plate.

Nolan Ryan (1972-79), whose own tenure with the Angels coincided with Reeses, often called Reese the nicest man in baseball. He must have been: Ryan named one of his sons “Reese,” in Jimmies honor.

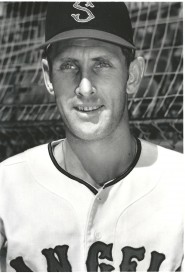

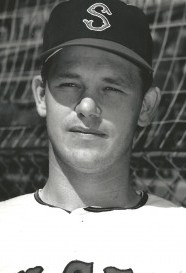

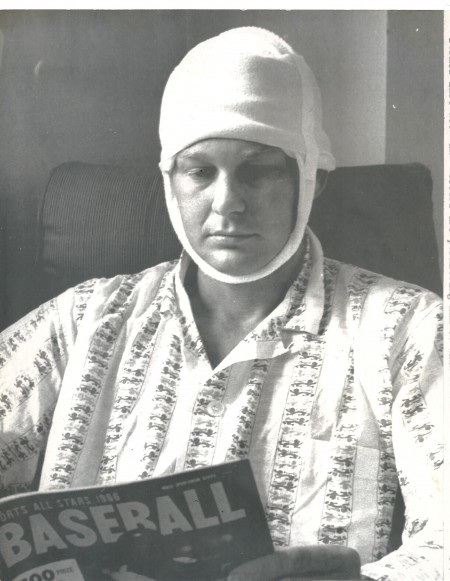

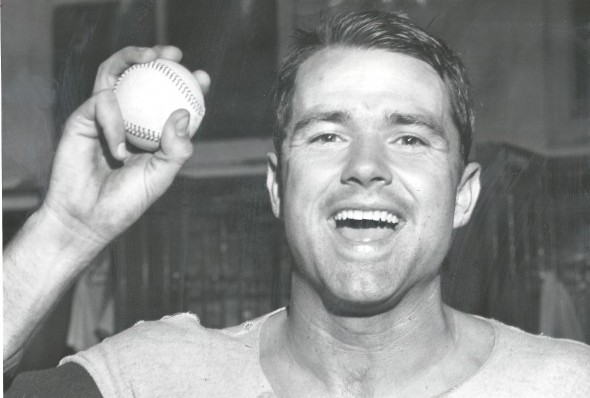

No one, as far as is known, is named after Jim Coates, aka The Mummy, for the funereal visage he presented. But he became Lemons most reliable starter.

While he won only 11 times in 21 outings, all his wins were complete games and he produced a 2.48 ERA. Coates’ victory total, ERA and strikeouts (138) led the staff (in a game in late May, Coates whiffed 16 batters and lost 1-0).

At age 33, Coates had almost exhausted his time in the majors — but not quite. On the basis of his 11 wins a 2.48 ERA, Coates drew a call-up to the big club on Aug. 14. He pitched for the MLB Angels for the balance of the year as a starter and reliever, making him unavailable to the PCL Angels for the playoffs.

Coates, who produced his best season in 1960 with the Yankees when he went 13-3 in 18 starts and made the AL All-Star team, remained in the Angels organization through 1970 (the Angels moved their PCL operation to Hawaii in 1969 after the Pilots arrived in Seattle). In his last year in Seattle (1968), Coates won 17 games.

Jim Bouton didn’t think much of the guy, tying a demeaning bow around Coates career in Ball Four by observing that Coates, after deliberately throwing at batters, would not get into the fights that followed.

Coates’ teammates witnessed just such an incident May 11 during a game against the Vancouver Mounties in Capilano Stadium (later Nat Bailey Stadium) when Coates threw a pitch high and tight to Ricardo Joseph of the Mounties, plunking him on the shoulder.

Joseph charged the mound, but before he could get to Coates, catcher Merritt Ranew, who had reached the majors with the Houston Colt 45s in 1962, raced after him and tackled him from behind, bloodying his chin, apparently with his mask.

Ranews tackle prompted both benches to empty, and fists flew for 10 minutes. Coates somehow avoided getting punched and stayed in the game. The first batter he faced after the melee was Tommie Reynolds, who bunted up the first base line, forcing Coates to field the ball. Reynolds took dead aim on Coates, determined to run him down.

Seeing this, Ranew again raced to Coates aid. Seeing that, Vancouvers Santiago Rosario dashed from the on-deck circle and clubbed Ranew over the head with his bat so hard the bat shattered.

Ranew did not move for some time, was carted off on a stretcher and taken to a Vancouver hospital where doctors determined he had internal bleeding in his brain and paralysis on the left side of his face.

The morning after the brawl, Coates stood in the lobby of Vancouvers Ramada Inn reading a newspaper when Joseph, who had failed to finish his charge on Coates because of Ranews intervention, appeared out of nowhere and whacked Coates hard in the face, then fled the lobby. A bloodied Coates notified Lemon, who called in Vancouver city detectives.

Coates told the detectives that Joseph was wearing a brown topcoat and a patch on his face, which witnesses verified. Coates pressed charges, and detectives rounded up Joseph.

In an interview with Reynolds, who had tried to run down Coates on the first base line, Reynolds said, A Seattle player told me before the game to stay loose because Coates would be throwing at us. Joseph told me the same thing. Coates throws at anyone who is colored.

The attack nearly killed Ranew, who suffered a blood clot in his brain and remained in the hospital for three weeks. Ranew sued the Mounties and Rosario and won his case in court before 1967 spring training.

Ranew returned to the PCL Angels in 1967, spent the following two years in the International League (Syracuse) and PCL (Vancouver), and then came back to Seattle as a member of the 1969 Pilots, for whom he hit .247 in 54 games.

A Georgia native, Ranew returned to his roots after retiring from baseball (1971) and launched a 35-year career training and showing cutting horses. He died on Oct. 18, 2011.

Although Coates led Seattle in wins with 11, Marty Pattin produced a better winning percentage (.818), going 9-2 with a 3.69 ERA after joining the Angels from Quad Cities, Californias Class A affiliate in the Midwest League. Pattin, like Ranew, played for the Pilots (1969), became an All-Star in 1971 with Milwaukee (the relocated Pilots) and won 114 MLB games in a career that ended in 1980.

Lemons Angels might have pulled away from Vancouver and Spokane far earlier than they did had outfielder Jay Johnstone remained with the club. But after the 20-year-old delivered a .340 batting average in the first half of the season, the MLB Angels summoned him. Johnstone split the next two years between the MLB Angels and PCL Angels before sticking in the majors for good. He ultimately had a 20-year major league career with eight teams.

With California, Johnstone preserved Clyde Wrights no-hitter against the Athletics on July 3, 1970, by making a spectacular, seventh-inning catch of a Reggie Jackson fly ball. With the 1976 Phillies, Johnstone went 7-for-9 in that years NLCS against the Cincinnati Reds. With the Dodgers, Johnstone whacked a two-run pinch homer in Game Four of the 1981 World Series against the Yankees.

A career .267 hitter, nothing Johnstone did in baseball branded him more than his pranks. He placed a soggy brownie inside Steve Garvey’s first base mitt, set teammates’ cleats on fire (known as “hot-footing”), cut out the crotch area of Rick Sutcliffe’s underwear, locked Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda in his office, dressed up as a groundskeeper and swept the Dodger Stadium infield between innings, nailed a teammate’s cleats to the floor, and replaced the celebrity photos in Lasorda’s office with pictures of himself, Jerry Reuss and Don Stanhouse.

Once, during pre-game warm ups, Johnstone climbed atop the Dodger dugout and, in full game uniform, walked through the field boxes at Dodger Stadium to the concession stand and purchased a hot dog. Johnstone also once dressed up in Lasorda’s uniform (with padding underneath) and ran out to the mound to talk to a pitcher while carrying Lasorda’s autobiography and a can of Slim Fast.

Second baseman Gotay might have been Lemons second-best hitter, at least in terms of average. But after batting .302 in 88 games, the MLB Angels swapped him to the Houston Astros for a minor leaguer on June 27, making Gotay a third missing piece from the PCL Angels title run.

Prior to his time (1965-66) in Seattle, Gotay spent 10 years in the majors with the Cardinals, Pirates and Angels. He had been St. Louiss regular shortstop in 1962, a reserve most of his career, and was known for his quirks.

Gotay once played a game with a sandwich stuffed into his back pocket. When he attempted to break up a double play, Gotay slid and the sandwich fell out of his pants, causing the opposing shortstop to slip and fall on the play.

For some reason, Gotay harbored a deep fear of crucifixes. He also practiced voodoo, which drove his roommate in Pittsburgh, Clemente, so crazy that Clemente begged the Pirates to either trade Gotay or assign him a new roommate. Eventually, the Pirates traded Gotay to St. Louis.

Gotays most notable major league accomplishment: From June 18-20, 1967, a year after leaving Seattle, he collected hits in eight consecutive at-bats while subbing for Joe Morgan, out on a military assignment.

After Gotay died of respiratory failure on July 4, 2008, in Nuevo Municipal de Florencio, in Fajardo, P.R, one obituary said, Its a good thing Julio Gotay came along when he did. Otherwise, (ESPNs) Chris Berman would have tortured us with Julio Gotay It On The Mountain.

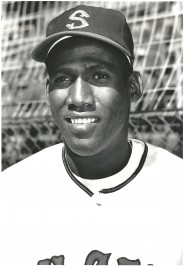

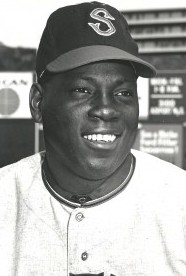

Unlike Coates, Johnstone and Gotay, outfielders Bubba Morton and Al Spangler spent the entire 1966 season with the PCL Angels, appearing in 141 and 127 games, respectively.

On the backside of his career when he arrived in Seattle at age 34, Morton hit .286 with 10 home runs and 60 RBIs after having to be talked into playing. When Morton received word that the MLB Angels were assigning him to the PCL, Morton nearly retired. But Lemon and Vanni convinced him the Seattle situation would be a good one.

Morton wound up playing four seasons with the Angels, split between MLB and the PCL. He spent his final season in Japan (1970) with the Toei Flyers.

An outfielder who grew up in a row house in Washington, D.C., Morton had a seven-year, 451-game run in the majors, finishing with a career .267 average with 14 homers and 128 RBIs. An excellent pinch hitter, he had his best season in 1967, hitting .313 in 80 games for the big-league Angels.

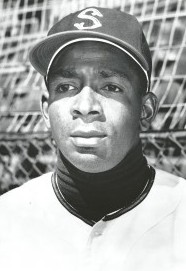

Three factoids about Morton: He held the distinction of being the first African American signed by the Detroit Tigers (1955), was the first black to play for the Durham Bulls (1957) and, during a stint with the Milwaukee Braves, roomed with Hank Aaron (1963). Back then, civil rights was an idea whose time had not yet come.

“Black players always had to stay in private homes on the road,” Morton told a reporter in 1997. “But I’ll tell you what kind of teammates I had in Durham they wouldn’t go and eat in a restaurant without me. Somebody would always go in and get sandwiches for everybody, then they’d bring them to the bus and we’d go on our way.”

Morton relocated to Seattle after his career ended and went to work as director of boys sports at the Bush School. In 1972, University of Washington athletic director Joe Kearney, who hired both Don James (football) and Marv Harshman (basketball), employed Morton to head up the schools baseball program, making him the first African American head coach in any sport at the UW.

“I got to be very close friends with him,” said former first baseman Don Mincher, one of Mortons teammates with the Angels. “He was a great player, and a great person. We talked about a lot of different aspects of life. He was so intelligent I would classify him as a perfect teammate.”

After his retirement from the UW in 1976, Morton went to work for Boeing. He died on Jan. 14, 2006, after a long illness. A Coast Guard reservist, Morton was buried at sea.

Mortons outfield mate, Spangler, is now 78. He hit .292 with seven home runs for the 1966 Angels after a five-year run in the majors, during which he played for the Braves and Colt 45s. Nicknamed Spanky, he drove in the first run in Colt 45s (Astros) history.

Spangler spent only one season with the PCL Angels, played two years in Tacoma, and got in 264 more major league games, all with the Cubs, before his career ended in 1971. Following his retirement as a player, Spangler served as a coach and minor league manager in the Cubs organization.

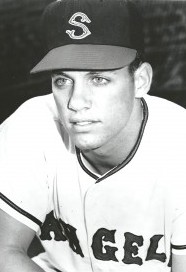

Andy Messersmith helped bury baseball owners a decade after playing for the 1966 Angels. Then a 20-year-old professional rookie, Messersmith appeared in 18 games, starting 12, and produced a 4-6 record with a 3.36 ERA. Messersmith reached the majors with the MLB Angels in 1968 and spent 12 years in the bigs, winning 130 games.

Messersmith had four (1971, 74-76) All-Star seasons and won two Gold Gloves (1974-75) with the Dodgers. His other notable achievement: Messersmith’s earned run average of 2.861 (over 12 MLB seasons) is the fourth lowest among starting pitchers whose careers began after the advent of the Live Ball Era in 1920, trailing only Whitey Ford (2.75), Sandy Koufax (2.75) and Jim Palmer (2.856), and barely ahead of Tom Seaver (2.862).

But nothing Messersmith did on the field had more lasting impact than the lending of his name to a grievance against baseball.

In 1975, along with Dave McNally, Messersmith challenged baseballs revered (by the owners) reserve clause, which bound a player to a team practically in perpetuity. On Dec. 23 that year, arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled on behalf of Messersmith and McNally, killing the reserve clause and opening up baseball to the free agency era.

When Messersmith won his first Gold Glove in 1974, he snapped Bob Gibsons Gold Glove-winning steak at nine (1965-73). When Aurelio Rodriguez won his first, in 1976 while playing for Detroit, he became the first American League third baseman since 1959 to beat out Brooks Robinson.

Rodriguez played in just 18 games for the 1966 Angels, batting .254. But a year later, he had become a semi-regular with the MLB Angels, and by 1970, when he went to Detroit in a 10-player swap that included former 31-game winner Denny McLain, he had become one of the American Leagues premier third basemen.

“Man, what an arm,” George Brett said of Rodriguez. “He’d field a grounder, pound his glove a few times, and still beat you by 10 feet.”

In addition to his Gold Glove, Rodriguez led AL third basemen in fielding percentage in 1976 and 1978. Playing for the Yankees in the 1981 World Series, he hit .417. Rodriguezs big-league career with seven teams ended in 1983, after which he played in the Mexican League until 1987, coached in the minor leagues for the Indians, and then returned to the Mexican League as a manager.

On Sept. 23, 2000, Rodriguez traveled back to Detroit. While walking with a woman on Detroits southwest side, a car jumped the curb and ran over him. The driver, who had a suspended license, was charged with manslaughter. Rodriguez was 52 at the time of his death.

Oddly, there have been only three players in major league history named Aurelio, two of whom played for Detroit, and all three were killed in automobile accidents.

A Cuban, Minervino Minnie Rojas became a one-year major league wonder after leaving the 1966 PCL Angels, for whom he went 5-3 with a 3.06 ERA. The following season, at age 33, Rojas became the MLB Angels closer and led the AL with 27 saves, a mark that stood as the franchise record until Donnie Moore broke it in 1985.

A year later, Rojas had just six saves. A year after that, he was back in the minors with Hawaii of the PCL and Jalisco of the Mexican League. His career came to an end when he was struck by a car and paralyzed.

On Opening Night, 1966, Rojas and catcher Jim Campanis (for part of the game) formed the Seattle battery in a 2-0 loss to Portland. Over the course of 107 games, 90 of them at catcher, Campanis hit .284 with 52 RBIs. After his one season with the PCL Angels, Campanis had a six-year major league career, never batting above the Mendoza Line in any of his stops.

One of those layovers came in Los Angeles, where Campanis was part of the Dodgers organization from the latter part of 1966 through mid-1968. Jims father, Al, the Dodgers general manager, made headlines on Dec. 16, 1968, when he traded his own flesh-and-blood to Kansas City for two minor leaguers and cash. Obviously, nepotism could only take Jim Campanis so far.

Neither John Olerud Sr., father of future Mainer John Jr., nor Mike White, son of Rainiers great Jo-Jo, contributed much to the 1966 Angels. Olerud Sr. hit just .163 for the Angels in a year split between Seattle and San Jose (California League). White hit only .222 in 77 games and finished his career with the Tacoma Cubs in 1969.

Cotton Nash also didnt play much for the 1966 Angels (nine games), but when he did he was arguably the best athlete on the field. A former University of Kentucky All-America basketball player, Nash had already logged time with the Los Angeles Lakers and San Francisco Warriors (1964-65) when he arrived in Seattle in a trade with San Diego.

Traded in 1967 by the MLB Angels to the White Sox for former Yankee first baseman Bill Skowron, Nash was on first base in the ninth inning on Sept. 10, 1967, when Joe Horlen threw a no-hitter. Nash made all three last-inning putouts.

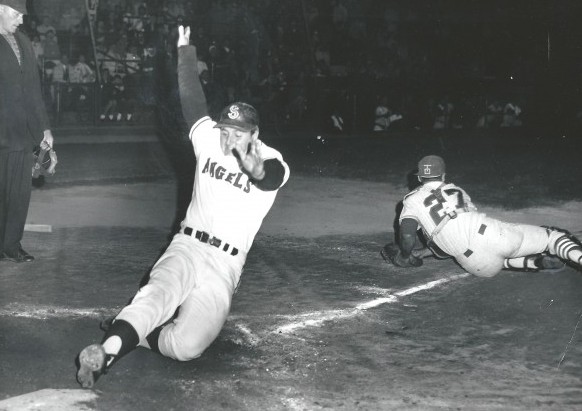

Tony Curry played for three teams — Portland, Oklahoma City and Seattle — in 1966, but found himself in an ideal situation when the regular season came to a close, in the PCL playoffs with the Angels. In Game 1 of the best-of-seven series on Sept. 7 in Tulsa, his two-run homer in the fifth became the decisive blow in Seattle’s 3-1 victory. The Angels also received a superb start from George Rubio (just 7-9 in the regular season), who finished with 12 strikeouts.

After the Angels lost Games 2 and 3 to fall behind 1-2, the series shifted to Sicks’ Stadium on Sept. 10, where a “surprisingly large crowd of 3,715,” according to the Post-Intelligencer, watched off-season hairstylist Bobby Locke, making his first start since Aug. 8, pitch eight innings of one-hit ball and finish with nine strikeouts and a walk as the Angels evened the series 2-2 with a 3-0 victory.

Due to heavy rain, Game 5 attracted just 1,606 to Sicks’. Rubio allowed seven hits and fanned seven in his second win of the series. Two unlikely hitters made a big impact for the Angels. Charlie Vinson, a .238 hitter in 148 regular-season games, and Tommy Summers, a .194 batter in 48 contests, both homered in Seattle’s 5-2 win.

Tulsa forced Game 7 by winning Game 6 2-1 in front of 5,521. Tulsa’s Tracy Stallard, a member of the Rainiers in 1962 when they were affiliated with the Red Sox (and the man who surrendered Roger Maris’ 61st home run in 1961), beat Howie Reed, who gave up two home runs for the second time in the series (also Game 2).

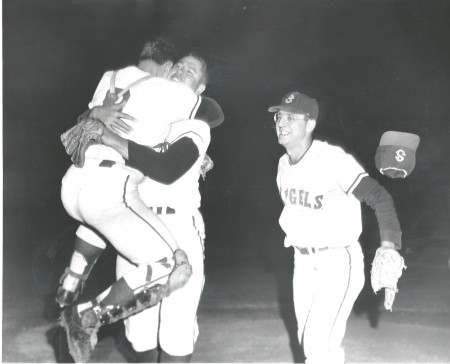

Game 7 drew a season-high 5,679. For all the past and future All-Stars and award winners that had constituted Seattle’s 62-player/pitcher roster, the man who ultimately made the biggest contribution to Seattle’s first PCL title since 1955 was a 5-8 shortstop the newspapers delighted in calling “Donnie The Midget,” “The Mighty Molecule,” and “that lulu of a leadoff man.”

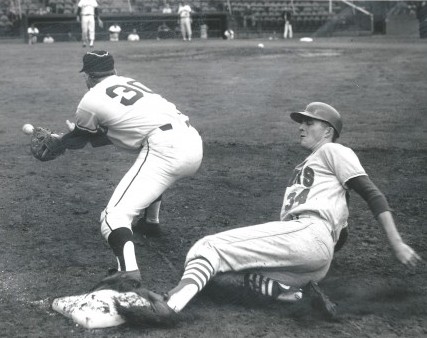

A native of Sapulpa, OK., Don Wallace began the 1966 season as a backup infielder (second, short). When Hector Torres went on the disabled list, Wallace took over at short, where he was stationed on the evening of Sept. 13.

McGlothlin fanned six over six innings and yielded to Bill Kelso, who tossed three innings of perfect relief. Spangler had two hits and two RBIs, but Wallace collected three hits and got on base four times. He also caught a ball initiating the game-ending double play, and was named MVP of the series.

“This Seattle team, as I’ve said, was my pet project,” said Milkes, who had flown up from Los Angeles to watch the PCL title series. “This has made me happier than anything I’ve done in baseball.”

Certainly the Pilots, three years later, disappointed Milkes by moving to Milwaukee, where owner Bud Selig reluctantly agreed him keep him employed only because the franchise had relocated so late in spring training. After one year under Selig, Milkes resigned, never to return to baseball.

In February of 1972, Milkes became the first GM of the New York Raiders, a franchise in the World Hockey Association. Milkes didn’t like it, resigning eight months into the job. A decade later, in 1981, he became GM of the Los Angeles Aztecs of the North American Soccer League, but that job lasted only a matter of months and, again, Milkes resigned.

A few months later, on Jan. 31, 1982, Milkes keeled over from a heart attack in a Los Angeles health club. The architect of the 1966 Angels, Seattle’s last pro baseball champions, was 58.

————————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

Mariners Can Spoil It For The Athletics — Why not. They’ve spoiled it for pretty much all of us again.