Few eras of University of Washington football remain as murky, or are harder to untangle, as the period from 1942 through 1947. Those years correspond to the head coaching tenure of a low-profile Texan named Ralph Pest Welch, who has never really intrigued UW football historians, and are problematic owing to the manner in which World War II disrupted all aspects of American life.

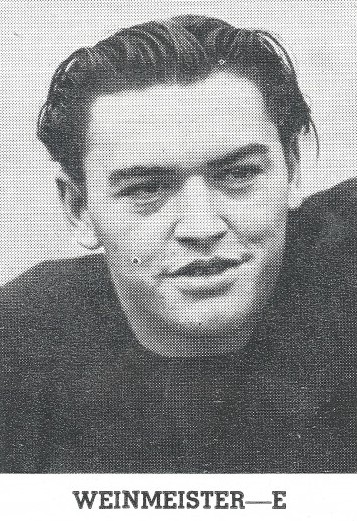

Welchs lack of historical magnetism might be traced to the fact that he followed colorful Jimmy Phelan (1930-41) into the job and never escaped the Irishmans considerable shadow. It also might be due to the fact that Welch never produced a dominant team, coached few memorable wins, and didn’t have any notable players aside from lineman Arnie Weinmeister (1942, 1946-47), who was not deemed good enough at UW to make the College Football Hall of Fame (South Bend, IN.) but found his way into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, OH., after making All-Pro five times in seven years with the New York Giants.

Welchs reign, however, was not without its merits. He produced five winning teams in six years and took the Huskies to the 1944 Rose Bowl. In fact, as we shall explain later, Welch took two different Husky teams to the 1944 Rose Bowl, the only one played between two members of the same conference (UW, USC).

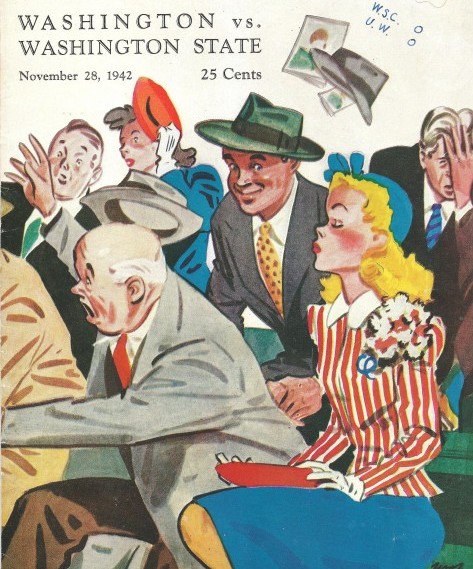

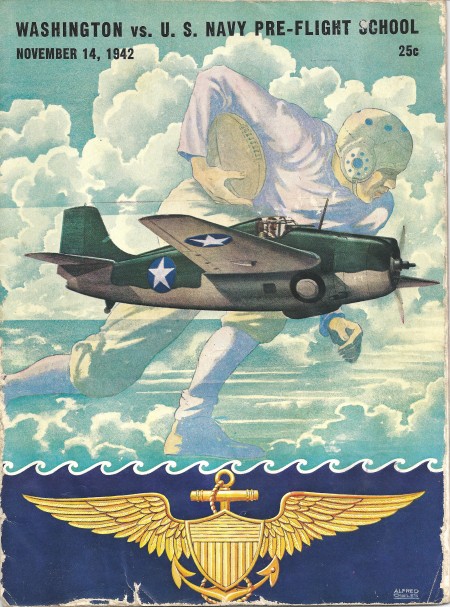

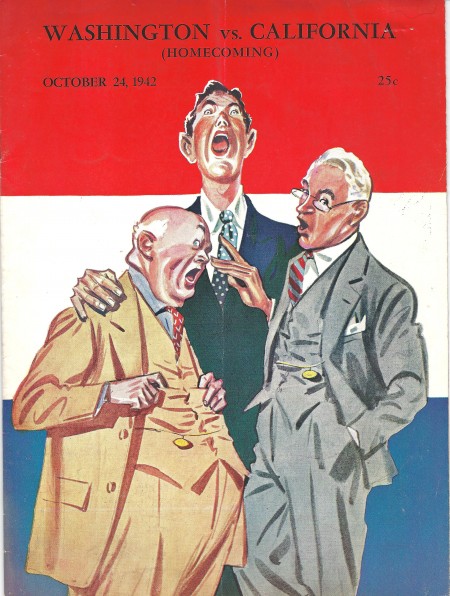

In 1942, Welchs Huskies were involved in a school-record six shutouts, including three 0-0 ties vs. Southern California, Navy Pre-Flight and Washington State. Only 10 0-0 ties have occurred in UW history and in only one other season 1932 did the Huskies play as many as two 0-0 ties.

Welch is the only head coach in UW history to defeat two opponents (Willamette and Whitman) by identical scores 71-0, no less (1944).

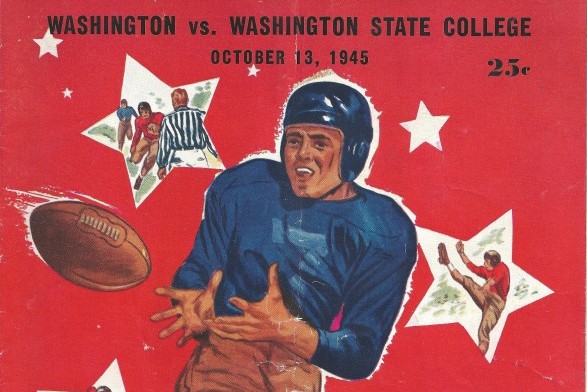

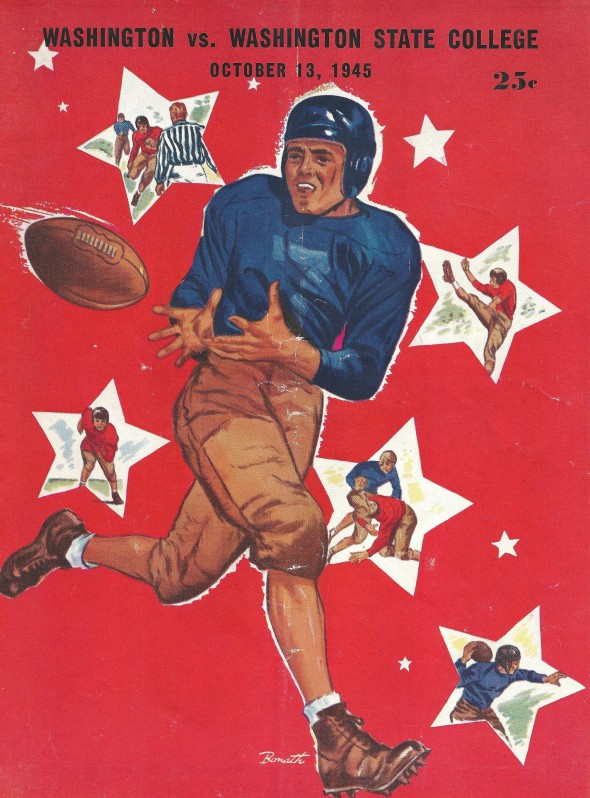

Hes the only UW head coach to twice face Washington State in one season (1945: the Huskies and Cougars split the contests, Washington winning 6-0 and losing 7-0).

Welch is also the only head man in school history to coach against his predecessor (Phelan, 1946, St. Mary’s), to coach against former UW players (1942), and to coach players who logged time at both Washington and Washington State.

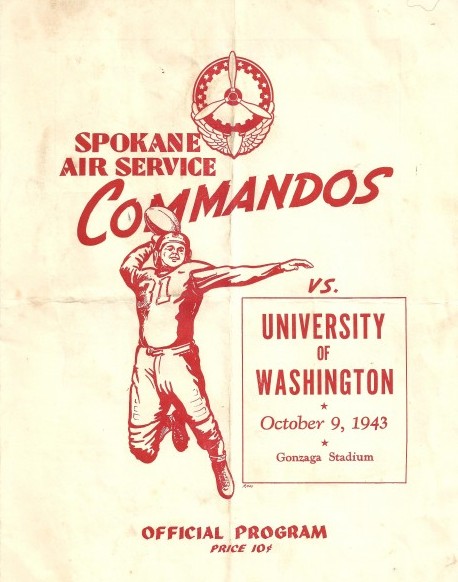

Finally, Welch is the only UW head coach whose schedules were weighted heavily with military teams, including Navy Pre-Flight (1942) , Spokane Air Command (1943, twice) and the March Field Flyers (1943), among others.

In some respects, its remarkable that Welch managed to produce a career record of 27-20-3 amid the confusion he faced.

Born Jan. 13, 1907, in Sherman, TX., Welch played college football at Purdue University under Phelan, earning All-America honors as a halfback in 1929 when he starred on the last undefeated, untied team (8-0-0) in Boilermakers history.

When Phelan departed Purdue to become head coach at Washington in 1930, the just-graduated Welch tagged along and served as his assistant in all but one of the 12 seasons (1930-41) that Phelan headed up the Huskies.

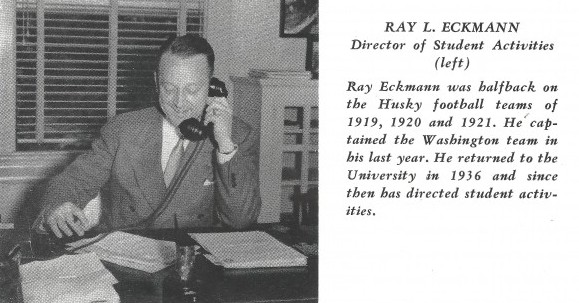

When Phelan wore out his welcome in 1941, at least in the considered opinion of athletic director Ray Eckmann, Welch and backfield coach Chester (Cotton) Wilcox, who had also played halfback (and served as captain) at Purdue, were ousted along with him.

Eckmann fancied Leon Brigham as Phelan’s replacement. Brigham had coached Garfield High School to 18 city championships in football, basketball and track in 23 years, his eight football titles coming between 1928-38, and had a flair for innovation. While Clark Shaughnessy of Stanford had generally been given credit for popularizing the T-formation in the early 1940s, Brigham had been using it as early as 1921, when Garfield hired him.

At the time, Brigham had been the Seattle Schools Athletic Director for four years (he would go on to oversee the construction of Memorial and Sealth stadiums, athletic fields at eight high schools and new gymnasiums at 10 high schools), and lobbied hard to become head coach of the Huskies.

But a number of UW players, headed by Walt Harrison, lobbied equally hard on Welchs behalf. Welch had become extremely popular with Husky players, and had a reputation as a great talent scout. So Eckmann re-hired Welch on a year-to-year basis (no contract), starting at $9,000 per season, which had been Phelans final salary.

He was one of the best, said Jimmy Cain, who played halfback under Welch (1934-36). He was a smart coach, a good assistant, and a great ballplayer in his day.

Unfortunately for Welch, he found himself hamstrung almost from the day he succeeded Phelan. Players came and went at such a dizzying rate that Welch could never count on fielding the same team two weeks in a row.

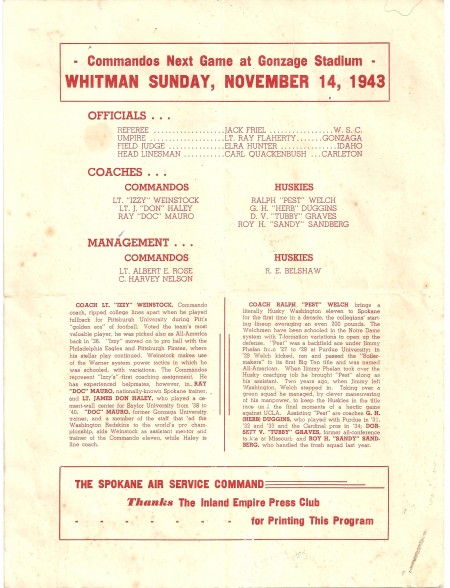

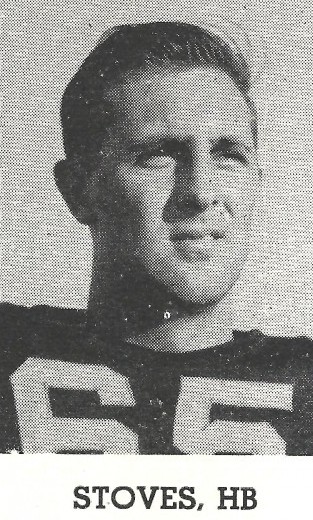

Washingtons last game of the 1943 regular season, for example, occurred on Oct. 30 against the Spokane Air Command, one of five service clubs Washington played between 1942-44. The Huskies had already defeated the Spokane Air Command earlier (Oct. 9) 47-12 UW back Jay Stoves ran for three TDs and threw for another and had no trouble handling the Commandos in the rematch, winning 41-7.

(Spokane Air Command included 33 players from 21 states and consisted mainly of ex-truck drivers, stock clerks and mechanics, a radio operator, a filing clerk and a welder.)

The second victory over the Commandos improved UWs record to 4-0 (because of the war, Washington played only four regular-season games in 1943), and earned Welch and the Huskies an invitation to participate in the Rose Bowl opposite USC, the Pacific Coast Conference Southern Division champion (war-time travel restrictions made it impossible for East, Midwest or Southern teams to play in Pasadena).

But by the time the Huskies arrived in Pasadena to face the Trojans, they had lost a dozen players to active military duty, including Stoves and Pete Susick, their two best backs.

Welch hastily filled a few of UWs roster holes with Navy V-12 trainees and 4-F draft rejects who had just arrived on the UW campus, but had only 28 players available for the Rose Bowl.

Welch even found a roster spot for a walk-on, Bill McGovern, who had played in Tacomas Stadium-Lincoln Thanksgiving Day game just a few weeks before the Rose Bowl (McGovern had an outstanding career as the UW center and was drafted the the Los Angeles Rams in 1947).

Largely on the basis of UWs 4-0 regular-season record, oddsmakers installed the Huskies as two-touchdown favorites to beat USC in the first Rose Bowl broadcast on the radio abroad to American servicemen (in western Europe, General Dwight D. Eisenhower allowed all troops not serving on the front lines to tune in and listen).

But the UW team that faced the Trojans bore little resemblance, in skill and speed, to the one that had gone undefeated. USC romped all over Welchs second edition of the 1943 Huskies, 29-0 (Washington was in USC territory only four times).

(The USC quarterback, Jim Hardy, threw three touchdown passes and later became both infamous and famous for the following: Quarterbacking the Chicago Cardinals, Hardy opened the 1950 season by setting an NFL record with eight interceptions in a loss to the Eagles. In Week 2, Hardy set an NFL record by throwing six touchdown passes against the Colts.)

A year later (1944), Washington embarked on a two-week trip to California for matches against USC and California. The Trojans routed Washington 38-7 in the first game, but the next week the Huskies, a 25-point underdog, produced one of the most inspired afternoons in UW history and stomped the Bears 33-7.

Right after the Cal game, eight Huskies, including five starters, were shipped to Navy and Marine training centers around the country. Among Welchs losses: Gordy Berlin, Washingtons best defensive player, who went to Parris Island, a Marine Corps training center in South Carolina.

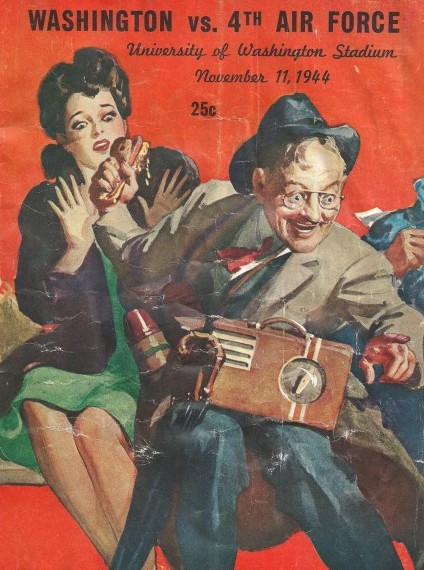

Welchs Huskies had no chance in their final two contests, losing by a combined 75-7 to two of the better service teams in the country, the Fourth Air Force Flyers of March Field (28-0) and the Second Air Force Superbombers (47-0), based out of Colorado Springs, CO.

The Flyers (based in Riverside, CA.) were representative of the service teams of the era. They featured two former All-America players, Jimmy Nelson of Alabama and Joe Williams of Ohio State, and six former All-Pacific Coast Conference standouts, including former Stanford end Hank Norberg and ex-UCLA receiver Woody Strode.

The Flyers arrived in Seattle they headquartered at Paine Field in Everett ranked 10th in the nation by the Associated Press. Ranked ahead of them: six college teams, topped by No. 1 Army, and three other service clubs, No. 3 Randolph Field (San Antonio, TX.) No. 5 Bainbridge (WA.) Navy Training School and No. 6 Iowa Pre-Flight (Des Moines, IA.), which had adopted the nickname Seahawks.

Two years earlier, in 1942, Washington played its first contest against a service team, Navy Pre-Flight, in a game held to benefit the armed forces (Army, Navy, Marines) based in Alaska. The Air Devils featured 38 former college standouts 11 of them All-Americans and were led by former Stanford quarterback Frankie Albert, who already had been drafted by the San Francisco 49ers.

The Air Devils roster also included Earl Younglove, a UW letterman from 1939-41 (named All-America in 1941), and ex-Husky Ed Keblusek. Younglove wore No. 35 and started at left end. Keblusek wore No. 43 and started at left guard. Their appearances marked the first and last time that ex-Huskies played against the Huskies in a regulation college game.

Welch also holds the distinction of having coached the eight, modern-era players who represented both Washington and Washington State in the Apple Cup, the so-called Couskies.

All switched schools during the war years when the Navy and Marines transferred students from school to school so they could take the courses required for officer candidate training.

The eight, all of whom launched their collegiate careers as Cougars: Al Akins (WSU 1942, 46-47; UW 1943); Hal Anderson (WSU 1942; UW 1946-47); Tag Christensen (WSU 1942, 47; UW 1943); Wally Kramer (WSU 1942-46; UW 1943); Vern Oliver (WSU 1942; UW 1943); Jay Stoves (WSU 1940-42; UW 1943); Jim Thompson (WSU 1942; UW 1946); Bill Ward (WSU 1941-42; UW 1943).

No individual symbolizes the war years better than Keith DeCourcy, an Oregon native who played college football for Dartmouth, Washington and Oregon in a career punctuated by a three-year hitch in the military.

After graduating from The Dalles (OR.) High School, the Navy sent DeCourcy, a teenage trainee, to Dartmouth. While there, DeCourcy played varsity football as a freshman after special wartime rules made it permissible for first-year collegians to participate in varsity athletics.

In those days, we all knew we would have to go into the service soon, so I returned to the Northwest and enrolled at Oregon State, DeCourcy told former Seattle Post-Intelligencer sports writer Don Fair.

While I was there, I passed the Navy V-12 test (a program designed to grant bachelor’s degrees to future Navy and Marine Corps officers) and was then sent to the University of Washington, which had that program.

In the late fall of 1943, after the Rose Bowl-bound Huskies lost a dozen players to active military duty, DeCourcy arrived on the UW campus. He turned out for football and played one quarter at fullback and linebacker for the Huskies on Jan. 1, 1944, in UWs 29-0 loss to USC.

Funny thing, DeCourcy told Fair, is that an Oregon State fraternity brother, Ted Ossowski, went into the same V-12 program, only he was sent to USC where he became a starting tackle and we played against each other in that 44 Rose Bowl.

The Washington team which went to the Rose Bowl didnt resemble the one which was undefeated, DeCourcy continued. Many of the top players were shipped out that November to either battlefield assignments, or for additional training at Marine Corps or Navy bases. Thats how I wound up the second-string fullback in that Rose Bowl.

DeCourcy competed for the UW track team in the spring of 1944, throwing the shot and javelin. The following fall, as Washingtons starting fullback, he racked up an astonishing 12 touchdowns in six games before the Navy beckoned him to active duty, forcing him to miss the seasons final two games.

Record keeping being haphazard in the war years (and even in the pre-war years), DeCourcys 72-point, 1944 season slipped through the cracks and never entered the UW record books, although, at the time, it ranked as one of the greatest individual seasons in school history.

DeCourcy scored four touchdowns (one on an interception) in a 40-6 victory over Willamette, four more in a 71-0 rout of Whitman and two in a 33-7 upset of California en route to his 72 points. For that, DeCourcy didnt even earn a letter. And then the Navy dispatched DeCourcy to Okinawa, where he served until World War II ended.

I never did play again for Washington, said DeCourcy, who went on to become a successful high school coach in Oregon.

When the war ended, I asked Coach Welch about returning to Washington, but he only offered me a grant-in-aid of $65 a month. That wasnt even a full ride.

So I went to Oregon, and Jim Aiken, who had just taken over as coach, offered me the full $75 ride with no questions asked. So thats where I finished out playing in 1948.

“And when I was all through five years of college football at Dartmouth, Washington and Oregon I still had another year of eligibility remaining as those wartime seasons didnt count against me.

The final game of DeCourcys college career occurred Jan. 1, 1948, when he played for Oregon against Southern Methodist in the Cotton Bowl. Thus, he played in two major New Years Day games representing two schools.

Welch did not suffer a losing season until 1947, when the Huskies went 3-6-0 and failed to score more than a touchdown in six of their nine games.

Shortly after UW wrapped up the campaign, the worst since 1929, with a 20-0 win over Washington State, Welch, at the urging of athletic director Harvey Cassill, submitted his letter of resignation — or so the official explanation had it.

What actually happened: Welch went to Los Angeles to watch Notre Dame practice for a Dec. 6 game at USC. Cassill added Notre Dame to Washington’s 1948 schedule (first time the Huskies met the Irish), and Welch wanted to compile an early scouting report.

While in Los Angeles, Welch received a message from Cassill “thanking him” for submitting a “well-worded” letter of resignation. Cassill had written Welch’s resignation letter.

Welch didn’t put up a protest, refused to say anything bad about Cassill, and quietly left campus and put some distance between himself and Washington athletics.

The following March, Welch announced that he would enter the insurance business in a partnership with Ed Nowogrowski, who had played fullback under Phelan from 1934-36.

Welch and Nowogrowski bought the agency of P.L. Bingay, renaming it Nowogroski-Welch Insurance Agency, and opened offices in the Carter Rice Building at 2929 Third Avenue.

Welch remained in Seattle for a decade and became a prominent amateur golfer. Then he returned to his native Texas, where he died on April 1, 1983, at the age of 76.

This is the full program cover for the 1945 Washington-Washington State game. The Huskies finished 6-3-0 under coach Ralph "Pest" Welch" after beating the Cougars 6-0. The Huskies played Washington State again later in the season and lost 7-0. 1945 is the only year when UW and WSU played twice in one season. / David Eskenazi Collection ——————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com