By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

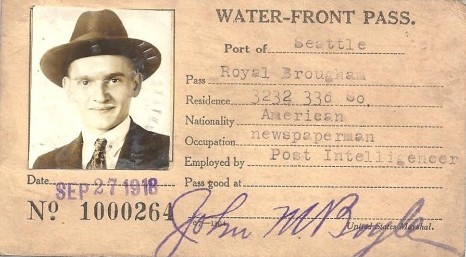

A Seattle institution now in its 78th year, the Star of the Year sports award program started with a simple question posed by Royal Brougham in his popular Seattle Post-Intelligencer column, The Morning After, published Feb. 23, 1936.

Who, Brougham queried his readers, was the Man of the Year in local athletics in the past 12-month period?

Employed at the newspaper since 1916, and a hunt-and-peck typist who used a Remington older than he was, Brougham listed a dozen sports personalities from 1935 that, in his view, merited consideration, and asked readers to provide feedback. A week after his initial column, Brougham began running a coupon in the newspaper labeled Morning After Man of the Year Contest to further encourage voting. As an inducement, Brougham offered $10 for the best essay of 75 words or less nominating the winning candidate.

Over the next month, Brougham issued frequent updates on the status of the voting. For the first few days, according to Brougham, University of Washington basketball coach Hec Edmundson (see Wayback Machine: Ace Coach Hec Edmundson) topped the balloting. Then Frank Foyston, head coach of the Seattle Sea Hawks hockey team, surged into the lead (see Wayback Machine: Frank Foyston & The Metropolitans).

Three weeks into Brougham’s contest, swimming coach Ray Daughters, famous for having coached Seattle’s Helene Madison to three Olympic gold medals at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics (see Wayback Machine: Queen Helene Madison) Games, became the voting leader.

Finally, on March 10, 1936, Brougham assembled a dozen of his cronies and sat them down for lunch at two tables opposite each other at the Washington Athletic Club. The group’s mission: to sort through the list of 12 nominees — none of them in attendance — vet their candidacies, and declare a winner. In the next day’s Post-Intelligencer (March 11), a large, bold headline stated:

Bobby Morris Voted Man of the Year

That Morris won surprised Brougham, Brougham’s readers and even the winner, Bobby Morris. An incredulous Morris told a reporter, ”There is probably some mistake here. I voted for Hec Edmundson and he should have won the honor.”

“Let’s you and I be frank about it — the dictum of the voters was surprising,” opined Brougham in his “Morning After” column. “And, yet, why not Bobby Morris? You ask, what has he accomplished?”

Before Royal weighs in, it would not be hyperbole to suggest that Brougham would be amazed at how his “Morning After” contest has evolved since its one-sentence start. The format has been revamped, the name has changed, the program has been held in a variety of venues (this year’s event is again at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25) and women, once verboten, were added to the show years ago.

Today, Broughams little clambake, as he quaintly liked to call it, is not so much a popularity contest as a red-carpet gala, replete with a VIP list that, over the decades, has featured Jesse Owens, Jack Dempsey (both pals of Brougham’s), Red Grange, Bob Feller, Otto Graham, Tom Harmon, Babe Zaharias, Johnny Unitas, Mel Allen, Stan Musial, Pancho Gonzalez, Crazy Legs Hirsch, and many others of similar profile.

The Sports Star of the Year has outlasted Brougham, who keeled over for good in the Kingdome press box in 1978, by more than three decades, and Brougham’s old newspaper, the Post-Intelligencer, by nearly three years (2009).

When Brougham launched what has become a civic institution, Seattle had no major professional sports or hydroplane races. Longacres (see Wayback Machine: Joe Gottsteins Racing Revival) was barely three years old.

UW football and basketball dominated the athletic agenda, followed by boxing and the Seattle Indians, a financially strapped member of the Pacific Coast League.

For those reasons, the early Man of the Year winners included, shall we say, some “unique” individuals.

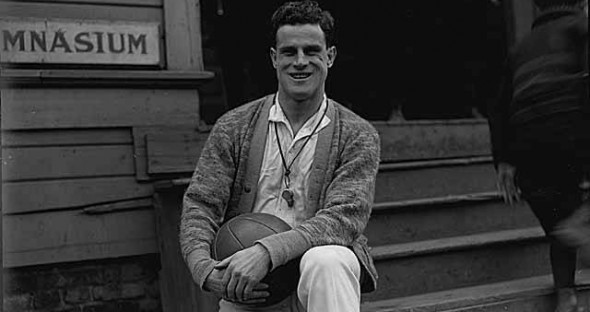

1935 / BOBBY MORRIS, Sports Referee

Many Post-Intelligencer readers wondered how a man, neither coach nor player, could prevail over a field that included Edmundson, Foyston, Daughters and an array of outstanding athletes.

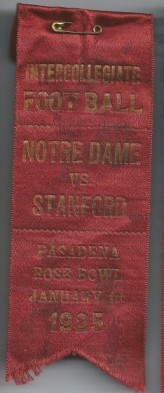

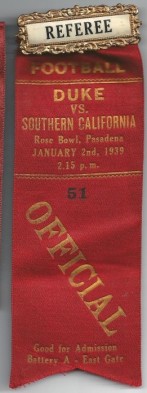

A few reasons: Morris was not only the most respected football and basketball referee on the West Coast (he officiated several Rose Bowls, including the 1935 match between Alabama and Stanford), and was well known to fans.

In the 1930s, and unlike today when such information is practically classified data, the Pacific Coast Conference regularly issued press releases listing game assignments for its football and basketball referees.

The newspaper guys turned the releases into four-to-five paragraph stories that usually made the front page of the sports section. Morris almost always drew the plum games, and readers knew it. As a partial consequence of that celebrity, Morris spoke at schools, clinics and sports-related gatherings. But Morris was more than a man in stripes.

“Listen!” Brougham wrote the day after Morris’ selection. “In one year the square-chinned little fellow licked the entire state of California. Because he was a product of the sand lots and never went to college, Morris was bitterly assailed by the football populace from Berkeley to the flower-bedecked stadium at Pasadena.

“By sheer courage and ability, he merited his selection as chief official of the titular Big Game at Palo Alto (Cal vs. Stanford) and later as referee-in-chief at the greatest gridiron spectacle in America — the Rose Bowl Classic.

“But officiating at football, basketball and baseball games is only one reason for Morris’ amazing popularity. Thousands of Seattle youngsters have been coached, advised and befriended by the stocky young man with curly hair.

“He fathered the American Legion baseball teams last summer; he gave freely of his services in coaching Seattle’s Japanese teams; he gave valuable aid to younger and less experienced referees.

“His services were in constant demand at high schools and luncheon clubs. While no softie in any sense of the word, he is a man of fine character, excellent habits, and the kind of leader you’d like your son to associate with.”

Morris attended Broadway High School, where he was a star athlete, after which he went to work for a Spalding sporting goods outlet and then the Seattle Parks Department.

Simultaneously, Morris officiated football and basketball games throughout the Pacific Coast Conference until 1940, when a leg injury and a new job — he became King County auditor — began to occupy his time. Morris remained at the county until 1969.

Near the end of his first term as auditor in 1946 (his primary task was ensuring the integrity of county elections), 11 years after his Man of the Year award, the West Seattle Herald wrote: “Bobby Morris, who at one time was one of the country’s outstanding basketball and football officials, was known for his integrity, courage and absolute fairness.

“He has carried those attributes into the office of county auditor and is recognized as one of our most respected and best-liked county officials. Bobby Morris should be re-elected to office.”

Had Brougham and his cronies opted to select a coach as the first Man of the Year, any of the three early voting leaders, Edmundson, Foyston and Daughters, would have made excellent winners.

Morris’s choice, Edmundson, had coached the Huskies to an 18-6 record in 1935 and a second-place finish in the PCC’s Northern Division. Foyston’s Sea Hawks won the North West Hockey Leagues regular-season title with a 20-9-3 record (lost in the playoffs to Vancouver), and Daughters had tutored swimming sensation Jack Medica, who would become the first in a litany of great athletes never named Man of the Year or Star of the Year.

In 1935, Medica, the UWs one-man swimming team, entered the National Collegiate Championships and swept three individual titles at 220, 440 and 1,500 yards, repeating his 1934 sweep. He would become a Man of the Year finalist again in 1936 after winning the 220, 440 and 1,500 at nationals for a third consecutive year, and then claim a gold and two silver medals at the Berlin Olympic Games.

Post-Intelligencer voters not only passed on Medica twice, they dismissed boxing star Freddie Steele three times (1935, 1936 and 1937), despite his unblemished 13-0 record in 1935, and even after The Tacoma Assassin became middleweight champion of the world in 1937 (see Wayback Machine: Al Hostak vs. Freddie Steele.)

In selecting Morris, voters also dismissed Kewpie Dick Barrett, the rubber-armed pitcher who had won 22 games for Dutch Ruether’s 1935 Seattle Indians. But Barrett had better Man of the Year luck than Medica and Steele. A finalist again in 1936 and 1937, he would finally win in 1940.

Morris played a significant role in Seattle sports beyond his officiating. He became chief judge at Longacres race track and served a term as president of the Seattle chapter of the National Football Foundation.

In addition, and together with UW football coach Jimmy Phelan, Morris helped convince Edo Vanni to forego a football scholarship at Washington, then negotiated Vanni’s first contract with Emil Sick’s Seattle Rainiers (1938).

One year after Morris’ death — April 18, 1970 — the City of Seattle renamed the Broadway Playfield the Bobby Morris Playfield (1635 11th Ave.).

1936 / AL ULBRICKSON, UW Rowing Coach

Ulbrickson could have won Brougham’s Man of the Year award several times during a career that spanned 1927-58. His crews won six Intercollegiate Rowing Association regattas (1936-37-40-41-48-50), defeated arch-rival California 20 times and famously beat the Russian national team in a 1958 challenge race that marked the first U.S. sports event broadcast (radio) from the Soviet Union.

But nothing Ulbrickson did eclipsed the feat of his 1936 varsity eight, the reason he became an easy choice for Brougham’s second Man of the Year award.

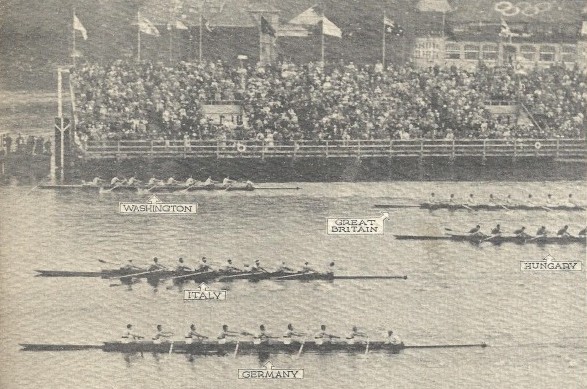

Competing in the Husky Clipper, a shell designed by George Pocock, Washington established a world record for 2,000 meters in the preliminaries, clocking 6:00.8. Then, in the medal race, the UW got off to a last-place start and trailed Germany and Italy by a substantial margin. But the Husky crew closed to within a length with 600 meters remaining and then picked up the pace.

The Huskies quickly passed Britain, Switzerland, Hungary and Germany. With about five strokes left, the Huskies whizzed past the Italians and Germans for the gold (margin of victory was a length and a quarter in a time of 6:24.4), infuriating race observer Adolph Hitler (see Wayback Machine: UW Bonanza at the 1936 Olympics).

The gold-medal crew consisted of Roger Morris (bow), Charles Day (2), Gordon B. Adam (3), John G. White (4), James B. McMillen (5), George E. Hunt (6), Joseph Rantz (7), Don B. Hume (8) and Robert G. Moch (cox).

Hume, in the No. 8 seat, and Moch, Washington’s cox, were among the 1936 Man of the Year nominees, as were 1935 finalists Daughters, Foyston, Edmundson, Medica, Steele and Barrett.

Ralph Bishop, the UW center who won a gold medal in Berlin as part of the USA Basketball team, received Man of the Year consideration, as did UW football Jimmy Phelan and his star back, Jimmy Cain, for their efforts in leading Washington to its first Rose Bowl since 1926.

But Ulbrickson’s triumph in Berlin, the first gold medal won in an Olympic Games by a Washington team, trumped everything.

Ulbrickson, whose 1948 4-oared crew won an Olympic gold on the Thames in London, died Nov. 7, 1980, at the age of 77.

1937 / JOHN CHERBERG, High School Football Coach

The first two Man of the Year contests featured male-only nominees. That changed for the 1937 program when the first woman, Mrs. Del Barkoff, a badminton player, appeared on the ballot with Edmundson, Phelan, Steele, Barrett and several new candidates, including boxer Al Hostak, Indians slugger Mike Hunt and UW football tackle Vic Markov (see Wayback Machine: Mike Hunt, ‘Old Baggy Pants’).

Phelan’s football Huskies (7-2-2) thumped Hawaii in the Pineapple Bowl (53-13), Steele had captured the National Boxing Association world middleweight title (Jan. 1 over Gorilla Jones) and successfully defended it three times. Barrett won 20 more games for the Indians (20-18), while teammate Hunt slugged 39 home runs.

Markov emerged as a big star for Phelan, named to five All-America teams (four first-team selections), but Man of the Year voters opted for Cowboy Johnny Cherberg, once a star back at Queen Anne High, who coached Cleveland High School to the Seattle City football championship (in a major upset, Cherberg’s Eagles knocked off heavily favored Garfield 2-0 in the title game on Thanksgiving Day).

Cherberg won the award at the right time in his athletic career. After moving to the University of Washington, first as a freshman coach under Pest Welch (see Wayback Machine: Pest Welch’s Crazy War Years), he could produce only a 10-18-2 record as head coach between 1953-56.

Cherberg’s undoing came in 1955, when four close losses and a tie in advance of a victory over Washington State, triggered a player revolt. Many UW players considered Cherberg borderline irrational. He wouldn’t allow his players to cross their legs while seated on the bench. He wouldn’t even permit them to whistle, or eat more than one dessert at training table.

“It was terrible,” halfback Dean Derby told a reporter years later. “Everything (with Cherberg) was about luck, a ritual.”

The player revolt brought down Cherberg, who retaliated, becoming one of the sources for a Sports Illustrated story that reported that Washington players had been paid money in excess of prescribed scholarship amounts, the money coming from a UW booster club slush fund. The revelation held up the Huskies as national cheaters.

As a result of the scandal, some UW players were suspended and some transferred. The UW athletic program was smacked with a two-year probation and a $52,000 fine, the stiffest in Pacific Coast Conference history, and affected every varsity sport.

In addition, the scandal cost athletic director Harvey Cassill his job and sparked investigations into the football programs at USC, UCLA and California, which led to the dissolution of the Pacific Coast Conference (see Wayback Machine: The Harvey Cassill Era).

The probation also laid the grounds for a delightfully epic outcome in UW sports history. With none of Washingtons programs eligible for national or postseason collegiate competition, Al Ulbrickson accepted an invitation to participate in the Henley Royal Regatta on the Thames, followed by a match race against the Soviet national champion Trud Club.

Washington’s stunning victory in Moscow remains one of the school’s greatest athletic achievements.

Cherberg didn’t say unemployed long. He immediately got himself elected the state’s lieutenant governor, a position he held for 32 years.

Cherberg resigned due to ill health in 1988 and died April 8, 1992, following a long illness. Flags in Olympia were lowered to half-staff.

1938 / FRED HUTCHINSON, Rainiers pitcher

Al Hostak didn’t win the 1938 Man of the Year award despite capturing the world middleweight title in a much-ballyhooed fight with Freddie Steele that attracted a Seattle-record throng of 35,000 to Civic Stadium.

Neither did Emil Sick, who had built a namesake ballpark for Seattle and introduced the Rainiers, the hottest ticket in town in 1938 (see Wayback Machine: The Rainiers & Pitchers of Beer), or three of his employees, manager Jack Lelivelt, outfielder Jo Jo White and infielder Alan Strange (see Wayback Machine: Jack Lelivelt’s Seattle Rainiers).

In fact, none of the nine other Man of the Year candidates stood much of a chance against 20-year-old Fred Hutchinson, who had, at 19, owned the summer of 1938 by compiling a 25-7 record with a 2.48 ERA and 145 strikeouts.

Hutchinson so impressed The Sporting News that it named him its Minor League Pitcher of the Year. But the numbers — and the award — were almost the least of his feats.

In just one year, the Franklin High grad had become a Seattle sensation, with fans anxiously staring and pointing at him wherever he wandered away from the ballpark. His scheduled outings, at home and on the road, became must-see events, circled on the calendar by big league scouts and curious fans.

Among the 25 victories he posted, two are still talked about fondly by Hutchinson aficionados and those who recall the glory of the Rainiers years.

On Aug. 12, Hutchinson’s 19th birthday, 16,354 fans crowded into Sicks’ Stadium and sat enthralled as Hutchinson won his 19th game.

Five days later, Hutchinson scored his 20th victory, 9-0 over the Sacramento Solons, allowing just three hits while striking out 12.

Hutchinson also had a perfect day at the plate, drawing a walk, hitting two singles and a home run, driving in four runs and scoring three times himself.

Lelivelt, his manager, described Hutchinson’s Aug. 17 performance as ”the greatest one-man exhibition Ive seen in all my years in baseball.”

Lelivelt, who had been involved in professional baseball since 1906, recognized that he would not be able to keep Hutchinson out of the major leagues for long, but hoped to have the popular teenager back in 1939. In fact, Lelivelt was asked frequently during the 1938 season where Hutchinson would pitch in 1939. Lelivelt always said, “My guess is Seattle.”

Didn’t happen. When, in the winter of 1938, the Rainiers received the opportunity to trade Hutchinson to the Detroit Tigers for three players and $50,000, they couldn’t say no.

Hutchinson subsequently won 95 major league games for the Tigers. He also managed the St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds, including the Reds’ 1961 World Series team. Hutchinson returned to Seattle in 1955, and guided the Rainiers to that years PCL title.

An Seattle icon then and now, Hutchinson died Nov. 12, 1964, at the age of 45 (see Wayback Machine: Hutch — A Man And An Award).

1939 / DEAN MCADAMS, UW football quarterback/punter

Lelivelt could have won the 1939 Man of the Year award for rebuilding the Rainiers into a team that won that year’s PCL pennant, and would win two more in succession.

Outfielder Jo Jo White, who played for the Detroit Tigers from 1932-38 before coming to Seattle in the Hutchinson trade, also had a big year as he led the Rainiers and PCL with 47 stolen bases. And many thought Henry Prusoff a viable candidate, especially for having recovered from a 1935 near-fatal back injury to reach the top 10 in singles in the U.S. tennis rankings.

None of them factored in the Man of the Year vote, but middleweight champion Al Hostak, a finalist for the third time (also 1937-38), did. After the first ballot, Hostak found himself tied with University of Washington football player Dean McAdams, who won the award when voters spoke a second time.

McAdams prevailed over a field that also included George Archie (Rainiers) not so much because he had been the best offensive player on a 4-5 Husky team, but because of his splendid play in a four-game stretch that featured victories over Stanford, Montana, California and Oregon, and Washington’s near upset (9-7) of No. 1-ranked Southern California in Los Angeles, and his efforts in that game.

Also a swimming and track letterman, McAdams kept the unranked Huskies in the game with a 47.5-yard punting average, which included a 57-yard punt that rolled dead on the USC three-yard line.

McAdams would have been an even more deserving Man of the Year winner in 1940 for quarterbacking Washington to a 7-2 record, a No. 10 national ranking, and helping get Washington to within one win of the Rose Bowl (a 20-10 loss to Stanford nixed a trip to Pasadena).

A year later (1941), McAdams became the second Husky selected in the first round of the NFL draft, going eighth overall to the Brooklyn Dodgers, four picks behind teammate Rudy Mucha, the fourth overall choice by the Cleveland Rams, who also appeared on the 1939 Man of the Year ballot.

McAdams mustered 22-games in the NFL from 1941-46, his career interrupted by World War II and a one-year hitch with the Seattle Bombers of the American Pro Football League (see Wayback Machine: The Seattle Bombers). But McAdams played six games for the Bears in 1946, when they won the NFL Championship.

A native of Caldwell, ID., McAdams spent most of his post-athletic life in Salem, OR., where ran a distributing business and a small farm. He returned to Seattle in 1994 and died from cancer Jan. 12, 1996, at age 78, in Seattle’s Meadowbrook Convalescent Center.

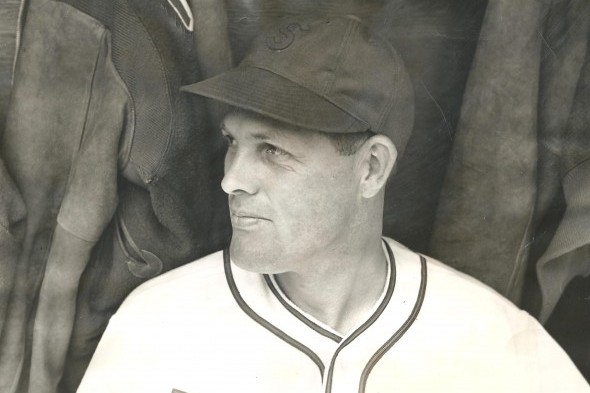

1940 / “KEWPIE” DICK BARRETT, Rainiers Pitching Ace

A Man of the Year nominee for the fourth time, 33-year-old “Kewpie” Dick Barrett faced a tough field for the 1940 award and might not have won — again — if the Rainiers hadn’t claimed the PCL title.

UW football guard Ray Frankowski, on the ballot for the first time and also a champion wrestler and fencer, was the first UW offensive lineman to twice be named first-team All-America. Golfer Jack Westland, another first timer, won the 1940 Pacific Northwest Amateur, his third consecutive year of doing so. And Ted Garhart, yet a third first-timer, led the UW to an undefeated season, which included a victory at the IRA Regatta in Poughkeepsie, NY.

Westland constructed one of the greatest careers by an athlete who went unrecognized by Man of the Year voters. In fact, he was never a finalist again after 1940, even though he won two Washington State Amateurs (1947-48), another Pacific Northwest Amateur (1951) and his capper, the 1952 U.S. Amateur.

MOY voters simply found it too hard to deny Barrett a fourth time, especially after he posted the statistically greatest season of his career. Barrett won 24 games, lost five and pitched 286 innings — a performance that earned him Minor League Pitcher of the Year accolades from The Sporting News.

The 24 victories marked the second in a string of four consecutive 20-win seasons for Barrett, who pitched for the Rainiers through 1942, then again (following a year in Portland) from 1946 through early 1949, when the Rainiers accommodated his request for a trade.

After winning the 1940 Man of the Year vote, what nobody could have imagined was that his signature moment with the Rainiers wouldn’t occur until eight years later, when he threw a perfect game May 16, 1948 at age 41 (see Wayback Machine: Kewpie Dick & The Rainiers).

Barrett didn’t look like much. He generally packed anywhere from 190 to 200 pounds on a 5-foot-9 chassis that made him look like a dimpled, roly-poly frump and one of the most unlikely perfect-game candidates anyone had seen. But he lasted 24 pro seasons — not without knowing how to pitch. Emmett Watson, the long-time Seattle columnist, caught Barrett in the bullpen late in Watson’s own baseball career.

He had a curveball that bowed like a waiter, Watson wrote after Barrett died, in near poverty, Oct. 30, 1966.

1941 / EARL CLICK CLARK, University of Washington trainer

Odd as it is now to reflect on the fact that a football/basketball referee once won the Man of the Year (1935), it’s equally quirky to see that an athletic trainer once won it as well. University of Washington trainer Earl “Click” Clark’s election in 1941 only served to buttress the widely held suspicion that, while Seattleites voted for the award, it was actually Brougham who made the final choice.

Clark doubtless merited recognition. An end on Gil Dobies 1912 football team (see Wayback Machine: Tweeting, 1911 Style), Clark transferred to Montana after one year, then returned to Washington in 1927, joining Enoch Bagshaw’s staff as an assistant (see Wayback Machine: Bagshaw’s Roaring Twenties).

A year later, Clark became head trainer, spending the next 28 years tending to the sprains and sore muscles rampant on the school’s athletic teams.

After Man of the Year voters tabbed Clark, Brougham wrote that Clark received it for his long-term service to the school.

The upshot of his victory: Clark essentially brought to an end the Man of the Year candidacy of Ray Frankowski, a nominee for the second and last time. Clark also prevailed over a future winner, a man Al Ulbrickson called the “greatest rower Ive ever seen.”

1942 / TED GARHART, University of Washington rower

Garhart first appeared on the ballot in 1940, losing to Barrett. Nominated again in 1941, he lost to Clark. In his third and final appearance on the ballot, Garhart contested six others for the award, including skier Matt Broze, UW football players Bob Erickson and Walt Harrison, Rainiers pitcher Hal Turpin and outfielder Bill Lawrence, and tennis player Bob Odman (see Wayback Machine: Farmer Hal Turpin).

Harrison twice was an All-Coast center for the Huskies, Turpin a 23-game winner for the 96-82 Rainiers, while Lawrence batted .310. But Garhart stroked the UW crew through three consecutive undefeated seasons, a feat unequaled by any other Husky rower, then or now.

The Garfield High alum also stroked the Huskies to IRA championships in 1940 and 1941, and might have added a third in 1942 had World War II not scotched a trip to the nationals, as well as any Olympic ambitions Garhart harbored.

When Garhart won the Man of the Year award, he was in the Marines, in officer’s training school in Quantico, VA. Due to military commitments, he would not attend the Man of the Year banquet until three years elapsed. When he did, Garhart said, ”Winning kind of surprised me. Seattle is basically a football town.”

Typical of success-oriented rowers, Garhart became an international investment banker, and in 1972 entered the Rowing Hall of Fame, the first UW individual athlete so honored. Garhart died of cancer in 2000 at age 80 in Green Valley, AZ.

1943 / HEC EDMUNDSON, UW Basketball/Track Coach

Bobby Morris’s pick to win the inaugural Man of the Year award, Hec Edmundson, finally won it nine years later, after his Huskies went 24-7 and participated in the NCAA Tournament.

Due to the depletion of star athletes caused by World War II, Edmundson didn’t have much competition for the award, facing off, among others, an archer and a bowler. Besides, it was about time for Edmundson, highly successful at coaching two sports, to win anyway.

Edmundson had been at UW since 1919, first as the school’s track coach, then as its basketball coach. By the time of his retirement, he had an amazing legacy.

His track teams won eight Northern Division titles, his basketball teams 12. Of the 13 track athletes in the Husky Hall of Fame, Edmundson worked with eight, including the school’s first three Summer Olympic medalists, discus thrower Gus Pope (1920, bronze), hurdler Steve Anderson (1928 silver) and shot putter Herman Brix (1928, silver).

Of the 18 All-America basketball players in UW history, Edmundson coached seven, starting with guard Alfie James in 1928 and ending with another guard, Battleship Bill Morris, in 1943. And of the 21 basketball players enshrined in the Husky Hall of Fame, Edmundson tutored 11.

The University of Washington’s original basketball pavilion, erected in 1929, was named after Hec Edmundson in 1948, a year after his forced retirement as basketball coach.

1944 / JIM MCCURDY, UW Football Player

The 1944 Man of the Year, Jim McCurdy, an All-Coast guard for a Washington team that made the 1944 Rose Bowl (lost to Southern California), came from one of Seattle’s most prominent families.

His father, Horace Winslow McCurdy, served as president and general manager of Puget Sound Bridge and Dredging, which built Husky Stadium (1920) and the first Lake Washington Floating Bridge (1940), among an array of other mass-scale construction projects. H.W. McCurdy was also a prime mover behind the establishment of the Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI).

Jim McCurdy, a member of broadcaster Bill Stern’s 1944 All-America team, an All-Coast selection that year and Washington’s Flaherty Award (most inspirational) winner, succeeded his father as president of Puget Sound Bridge and Dredging after the company was sold to Lockheed Aircraft Corp. (the Hood Canal Bridge was built during Jim’s presidency).

In addition to its extensive involvement in maritime research, the McCurdy family became a major contributor to the UW rowing program.

After Jim’s older brother, Tom, passed away, the McCurdy family established the Thomas W. McCurdy Memorial Scholarship Fund at the UW. The school’s athletic department took control of the endowment in 1977 for a specific purpose: There is a requirement that there will, at all times, be a modern shell in the boat house named for Tomas W. McCurdy, a one-time UW oarsman who died of a disease he contracted during the Korean War.”

The most recent shell bearing Tom McCurdy’s name ”the Tom McCurdy 52″, a state-of-the-art eight, was christened in 2010. By that time, younger brother Jim had attended more than 60 consecutive Man of the Year/Star of the Year sports banquets.

1945 / HARRY GIVAN, Golf

Givan not only created the Seattle Open in 1945 and served as the tournament’s director, he finished second to Byron Nelson at Broadmoor Golf Club (Nelson shot 62-68-63-66 259 for four rounds, a PGA record that would stand for 10 years).

In Man of the Year voting, Givan finished ahead of a field that included UW football players Gordie Hungar and Bill McGovern, Husky basketball star Sammy White and, for the first time, a pair of conservationists, George Gunn and Steve Morrissey.

Givan had a long and impressive sports resume at the time he won the Man of the Year. He graduated from Lincoln High, where he was all-city in baseball three times and in basketball twice. He also played for the school’s golf team after purchasing clubs that he bought with money he had made boxing under an assumed name.

Givan had, according to two published reports, 19 scholarship offers coming out of Lincoln, and was also offered a pro baseball contract. But Givan opted to attend the University of Washington, where he captained the golf team.

Givan won the Pacific Northwest Golf Association Amateur five times and the Seattle Amateur four times. A two-time Walker Cup member and the winner of the 1936 Washington State Open, Givan also won the Northwest Open in 1942 and prevailed in exhibition matches against Sam Snead, Bobby Jones and Byron Nelson.

Golf wasn’t all Givan did. An insurance executive, he joined a group of businessmen a decade after his Man of the Year selection, and helped them secure funding and land for Northwest Hospital in North Seattle. Givan died Dec. 16, 1999, at the age of 88.

1946 / STEVE MORRISSEY, Conservation

Swimming coach Ray Daughters had not appeared on the Man of the Year ballot since 1936, the event’s second year. But he was back on it in 1946, along with shell designer George Pocock, who hadn’t been on the ballot since 1937, and Jo Jo White, missing since 1941.

All were trumped by Steve Morrissey, a 45-year-old, Seattle-based conservationist and outdoor enthusiast, who presided over a highly active hunting and fishing organization, the state Sportsman’s Council, as well as the King County Sports Council.

More specifically, Morrissey had led a successful fight against a referendum (No. 26) that would have inflicted severe damage on sport fishing by allowing commercial development in environmentally sensitive areas. Seventy-five members of a Brougham-assembled tribunal made Morrissey its choice.

Morrissey defeated shell builder George Pocock and Rainiers’ outfielder Jo Jo White in a “photo finish,” recognizing Morrissey as “the coach of the biggest team in the state — 350,000 hunters and fishermen — and his untiring efforts towards the betterment of the Evergreen State as a sportsman’s paradise.”

“It was a just reward for unselfish leadership, especially in the sportsmen’s vigorous campaign against Referendum 26, which was snowed under by the biggest majority in the state’s political history,” Harold Torbergson wrote in the Post-Inteligencer.

Morrissey died in 1988 in Okanogan at 87.

1947 / LEON BRIGHAM, High Schools, Administrator

Brigham won the Man of the Year award while in his fourth year as athletic director at Seattle Schools. He defeated a list of nominees that included pairs skaters Peter and Karol Kennedy, shell designer George Pocock (third time on the ballot), and Husky booster and Rainiers executive Torchy Torrance.

Brigham coached Garfield High School to 18 city championships in football, track and basketball in a 23-year span, and had a flair for innovation (his eight football titles came between 1928-38). While Clark Shaughnessy of Stanford is generally credited with popularizing the T-formation in the early 1940s, Brigham was using it as early as 1921, when Garfield hired him.

As the athletic director for Seattle Schools, Brigham oversaw construction of Memorial and Sealth stadiums, athletic fields at eight high schools and new gyms at 10 high schools.

In all his years of involvement in Seattle athletics, Brigham had only one major setback. After the UW fired football coach Jimmy Phelan was fired in 1941, Brigham lobbied athletic director Harvey Cassill hard for the job. But Brigham lost out to Ralph Pest Welch.

After the completion of Memorial Stadium at the Seattle Center, the scoreboard was named in his honor. Brigham retired in 1961 and died July 11, 1987.

1948 / GEORGE POCOCK, Rowing

George Pocock finally won the Man of the Year award the fourth time he was nominated. Given the national and international popularity of his racing shells, Pocock could have been Man of the Year in any year since 1935, and no one would have been disappointed.

Pocock set up his boat-building business near the UW campus at the urging of Hiram Conibear. While Conibear re-invented the mechanics of the stroke, revolutionizing rowing, Pocock (and his brother) changed the art of boat building through various innovations, including sliding seats, lightweight oars, special oarlocks, and a unique steering mechanism, replacing the tiller.

Using shells designed by Pocock, Washington rose to rowing prominence, winning the first of many national championships in 1923 at the IRA Regatta in Poughkeepsie, NY.

By the early 1920s, Pocock began receiving orders for his unique shells from all over the world. Pocock ultimately supplied nearly every college and university in the country with his craftsmanship, many of which were used by gold-medal crews in the Olympics. Pocock remained at the UW for many years, frequently acting as an unofficial assistant and advisor to the UW coaching staff.

Pocock died March 9, 1976 at age 81 (see Wayback Machine: 10 Intriguing Olympians).

1949 / GORDON GLISSON, Horse Racing

Dozens have been nominated over the years, including Gary Stevens (1984), Gary Baze (1985), Vicky Aragon (1986) and Gary Boulanger (1989), but only one thoroughbred jockey ever strutted off with the Man/Star of the Year award, Gordon Glisson in 1949.

Glisson came out ahead over an impressive cast that included UW football players Roland Kirkby, one of only three Huskies to have their jersey numbers retired, and Arnie Weinmeister, one of the greatest players in school history.

Born in Winnsboro, SC., Glisson moved to Seattle with his mother at age 15 and began working at Longacres.

Within a few years, he received his apprenticeship and elected to spend the winter of 1948-49 competing against the likes of Eddie Arcaro at Santa Anita. Glisson’s 57 wins topped all North American riders in 1949, and marked the second-highest apprentice total at that time.

In 1950, a year after winning the Man of the Year balloting, Glisson became the first recipient of the newly created George Woolf Memorial Jockey Award, given to a successful jockey who demonstrates high standards of personal and professional conduct.

Among Glisson’s major career victories: 1949 Kentucky Oaks, 1949 Santa Anita Derby, 1952 San Luis Rey Handicap and 1955 Hollywood Gold Cup.

Glisson was living in Ojai, CA., when he died in 1997 at the Sherman Oaks Burn Center following an accident at his home.

—————————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

Man of the Year Winners (1935-76)

Star of the Year Winners (1977-11)

————————————————

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets are $100 for VIP Reception and Premium Award Show Seating; $80 for VIP Reception and Award Show Seating; and $35 for Show Only Seating. The VIP Reception offers complimentary drinks and appetizers. Tickets can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets are $100 for VIP Reception and Premium Award Show Seating; $80 for VIP Reception and Award Show Seating; and $35 for Show Only Seating. The VIP Reception offers complimentary drinks and appetizers. Tickets can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.