By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

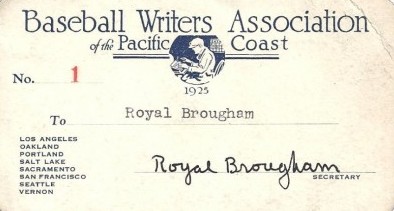

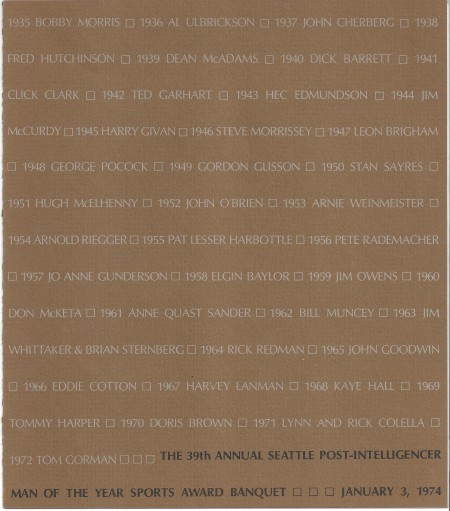

In the decades before Seattle became a major league sports city, Royal Brougham’ s Man of the Year sports awards program (78th edition is Jan. 25 at Benaroyal Hall) mostly featured amateurs, the nominees including badminton (1937, 1939) players, conservationists (1944, 1945), playfield operators (1947, 1948), an archer (1943), a squash athlete (1948), even a Labrador retriever (1952).

The first winner, Bobby Morris in 1935, was a football/basketball referee (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year 1930-39). Through the years, lots of University of Washington athletes and coaches won, as did several golfers and two high school administrators. One year (1954), a trapshooter (Arnold Riegger) became Man of the Year (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year 1950-59)

In the 1970s, with Seattle having achieved big league status in football (NFL), basketball (NBA) and baseball (MLB), Brougham’s awards program began to reflect that change.

Between 1973 and 1980, a SuperSonics player or coach claimed Man of the Year accolades four times. In the 1980s, the Seahawks produced five winners in a six-year span. Then, starting with Ken Griffey Jr. in 1989, a Mariner won eight times in 15 years.

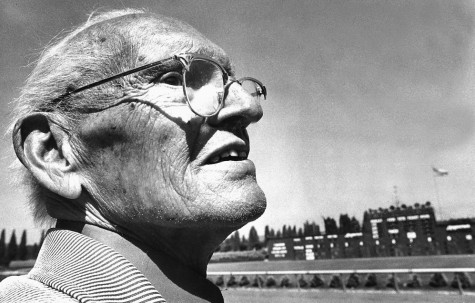

Brougham didnt live to see professionals come to dominate what he quaintly liked to call his ”little clambake.” On Oct. 30, 1978, two months away from presenting the 44th Man of the Year award, Brougham collapsed in the Kingdome press box while watching a Seahawks-Denver Broncos football game. Medics rushed Brougham to Swedish Hospital, where he died later that night of a ruptured aorta.

In his day, Brougham hadn’t missed much. A 68-year veteran of the Post-Intelligencer, Brougham’s first big assignment for the newspaper occurred in 1917, when he covered the Seattle Metropolitans Stanley Cup victory over the Montreal Canadiens (see Wayback Machine: Frank Foyston & The Metropolitans) at the Seattle Ice Arena.

In his last, Brougham sat in the Rose Bowl press box in January of 1978 and watched Washington’s Warren Moon engineer a 27-20 victory over Michigan. By that time, Brougham hobbled about with the aid of two canes, one fashioned from a tennis racquet, the other from a golf club.

In a story on Brougham in the Post-Intelligencer a quarter of a century after his death, Dan Raley wrote, “Most local sports fans under 40 couldn’t tell you who Brougham was or what he did. Yet from the outbreak of World War I through the aftermath of the Vietnam War, Brougham was a slight man who became a larger-than-life character, persistently sticking his nose into everything involving the local sporting landscape.

“When he wasn’t extolling the virtues of Seattle, Brougham was reaching out to some of the nation’s biggest athletic names — among them Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, Jessie Owens and Babe Didrikson Zaharias — and coaxing them to travel to the Pacific Northwest as his guest for some charitable cause.”

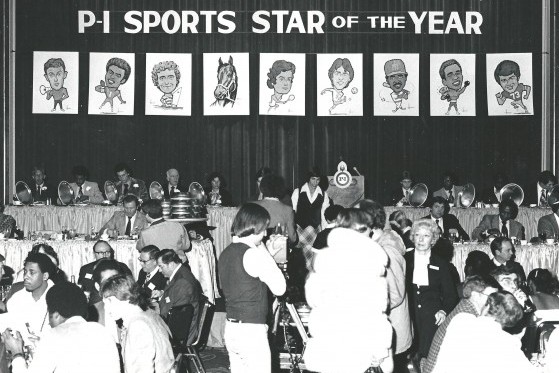

Brougham relied on the tennis racquet to get around the Olympic Hotel in what proved to be his last banquet, which honored Moon, not as Man of the Year, but as the first Sports Star of the Year.

The name change was made in order to more fully recognize the increasing number of women on the ballot, six of whom won before the name was changed, including two to start the 1970s.

1970 / DORIS BROWN HERITAGE, Track

Man of the Year voting abounds in curiosities. Al Hostak couldn’t win in a year (1938) in which he won the world middleweight title (see Wayback Machine: Freddie Steele vs. Al Hostak). The great UW basketball player Bob Houbregs failed to win in 1953, the year the NCAA named him its Player of the Year (see Wayback Machine: Bob Houbregs & The ’53 Final Four).

Washington’s Bob Schloredt (1960) failed to make the ballot after claiming his second Rose Bowl MVP, and Lenny Wilkens appeared on the Man of the Year ballot three times, but not in the year (1972) he won the NBA All-Star Games Most Valuable Player trophy.

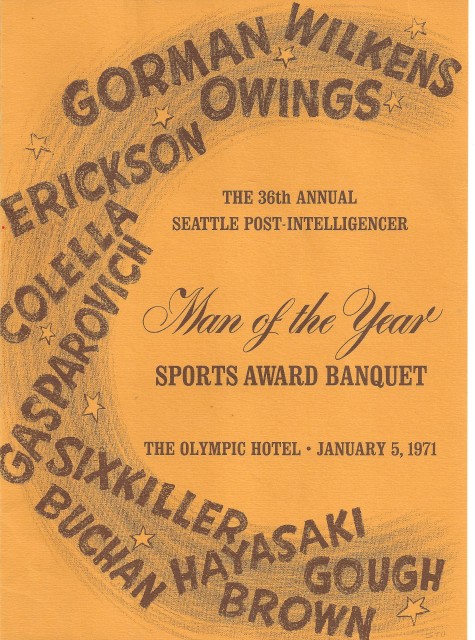

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the 1970 Man of the Year program was not that Doris Brown, the fabulous distance runner from Seattle Pacific, became the fifth woman judged the best on the ballot, but that Brown somehow managed to leave both Sonny Sixkiller (see Wayback Machine: Sixkiller Becomes An Icon) and Larry Owings in her wake.

Royal Brougham’s Supreme Court, the tribunal that selected candidates and determined MOY winners, assembled an impressive slate in addition to Sixkiller and Owings.

An All-Star again, Wilkens returned to the ballot for the second consecutive year, gymnast Yoshi Haywasaki (NCAA all-around champion) for the second time in his career, and emerging tennis star Tom Gorman for the first time.

But no Seattle-based athlete attracted more attention than Sixkiller, nor had any developed as many fans or achieved his level of celebrity. Sixkiller wasn’t so much a quarterback as he was a phenomenon.

Practically from the moment Sixkiller engineered a 42-16 victory over Michigan State in his first college game (Sept. 19, 1970), the UW sophomore was well on his way to achieving icon status.

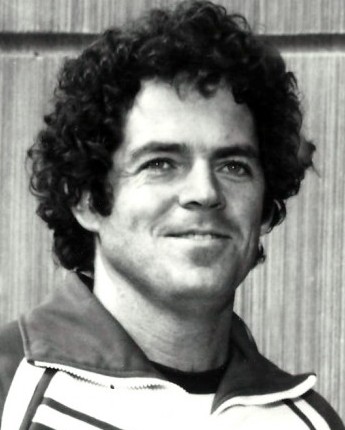

A UW wrestler, Owings labored far from the athletic spotlight that shone constantly on Sixkiller. But on March 28, 1970, Owings accomplished a feat that would resonate across the years, even across decades, and now has been witnessed by more than 200,000 on You Tube. The particulars:

Dan Gable had never lost a wrestling match in high school (64 consecutive victories), nor at Iowa State University. When he stepped onto the mat at McGaw Hall on the Northwestern campus, he was a three-time All-America, two-time NCAA champion and the winner of 181 consecutive matches, including his previous five by pins.

His seemingly in-over-his-head opponent in the 142-pound NCAA final: UW sophomore Owings, who trailed Gable 10-9 with 25 seconds left but had a near pin and a takedown to win the match, setting the wrestling world on its collective ear.

An eight-minute video of Owings’ triumph was subsequently placed on permanent display in the Wrestling Hall of Fame in Stillwater, OK.

Noted the Chicago Tribune: ”Owings gave us one of the most unforgettable moments in the history of wrestling and possibly all sport.”

Owings would go on to win two more Pac-8 titles (1971-72), would reach the NCAA finals as both a junior and a senior, and would place second at the 1972 Olympic Trials.

In all, Owings defeated four NCAA champions, 10 Olympic champions, two Olympic podium finishers and two world champions during his career.

But he couldn’t take down Doris Brown at the 1970 Man of the Year banquet.

Brown had been great internationally for nearly a decade. She would have made her first U.S. Olympic team in 1964 had it not been for a broken foot. In 1966, she was the first woman to run a sub-five-minute mile, clocking 4:52. She had participated in the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, and had been the AAU Female Athlete of the Year in 1969.

Most impressive, though, was that Brown had won an unprecedented four consecutive world cross country Championships (no other American woman had won even one) in locales as diverse as Barry, Wales (1967), Blackburn, England (1968), Clydebank, Scotland (1969) and Frederick, MD. (1970).

At the time Brown won the Man of the Year award, joining golfer Pat Lesser (1955), golfer JoAnne Gunderson Carner (1957) [see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year, 1950-59], golfer Anne Quast Decker (1961) and swimmer Kaye Hall (1968) [see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year, 1960-69] as the event’s only female winners, she stood only at mid-career.

Brown captured a fifth straight world cross country title in 1971 (San Sebastian, Spain), won a silver medal (800 meters) at the 1971 Pan American Games in Cali, Colombia, set world records at 3,000 meters and two miles in 1971, and represented the U.S. in the 1972 Olympics.

Brown entered the Track & Field Hall of Fame in 1990, the U.S. Track Coaches Hall of Fame in 1999, the National Distance Running Hall of Fame in 2002, and spent more than 30 years coaching at Seattle Pacific, 18 of her runners earning All-America recognition.

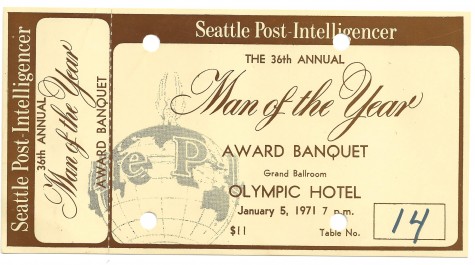

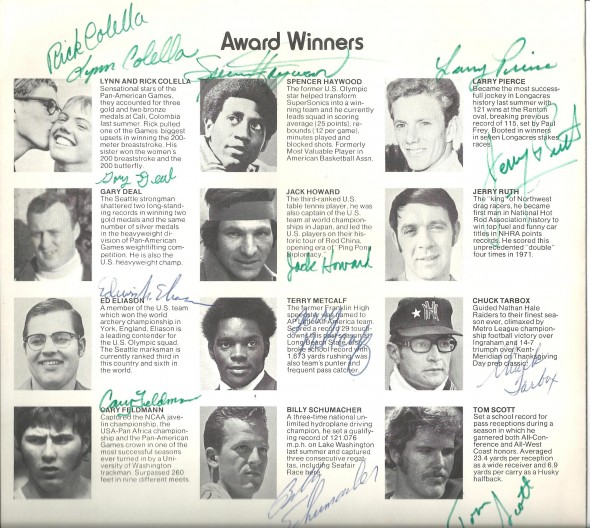

1971 / LYNN & RICK COLELLA, Swimming

Spencer Haywood loomed as the favorite to win the 1971 Man of the Year for two reasons: He was the leading scorer for the 1970-71 SuperSonics (20.2 PPG) and had the requisite high profile. And pre-banquet sentiment was that it was time that a representative of Seattle’s first major professional sports franchise (see Wayback Machine: Two Trojans Who Changed Seattle) topped the ballot, especially after MOY voters had rejected the candidacies of Bob Rule in 1968 and Lenny Wilkens in both 1969-70.

And if not Haywood, banquet goers had several intriguing choices, among them Cary Feldman, who had won the javelin (259 feet) at the NCAA Championships in Husky Stadium by upsetting American record holder Mark Murro of Arizona State.

Feldman had become UW’s first NCAA track champion since Brian Sternberg won the pole vault in 1963 (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of the Year (1960-69).

In addition, Billy The Kid Schumacher, the popular driver of the Pay N Pak, and Terry Metcalf of Franklin High, one of the greatest football talents to emerge from the local prep ranks in years, were viable candidates (Schumacher won the Seafair Trophy race).

Weighing its choices, the Man of Year voting tribunal decided upon the sister-brother swimming tandem of Lynn and Rick Colella, who joined pole valuter Sternberg and mountain climber Jim Whittaker (1963) as the second set of co-winners in Man of the Year history.

The Colellas forged national reputations by the time they collected their awards at the Olympic Hotel. Rick was a two-time All-America, a Pac-8 Conference event (breaststroke) titleholder, and was coming off his first international success, a gold medal in the 200 breaststroke at the 1971 Pan American Games in Cali, Colombia.

If anything, Lynn, a MOY finalist in 1970 after winning gold medals in the 100 and 200 butterfly at the U.S. Spring Championships, produced an even better year than her younger brother.

She earned two golds — 200 butterfly, 200 breaststroke — and a relay silver at the 1971 Pan Ams. In addition, Lynn had set an American record in the 200 breaststroke at the National AAU Indoor Championships, at which she also finished second in the 200 butterfly.

On top of that, Lynn won a 100-meter breaststroke gold at the 1971 U.S. Spring Championships.

Like many Man of the Year winners, the best athletic work done by the Colellas had yet to occur. Both became Olympians, Lynn in 1972 (silver medal in the 200 butterfly) and Rick in 1972 and 1976 (won a bronze in Montreal in the 200 breaststroke).

Lynn also won bronze medals (200 breaststroke, 200 butterfly) at the 1973 World Championships in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, while Rick captured gold and silver medals at the 1975 World Championships in Cali, Colombia.

The best team-sport athlete on the 1971 ballot, aside from Haywood, turned out to be Metcalf, who had a six-year NFL career (with the Cardinals and Redskins), during which he made three Pro Bowl appearances.

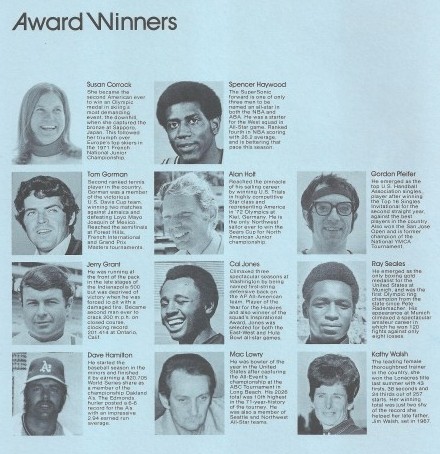

1972 / TOM GORMAN, Tennis

No one brought a larger profile to the 1972 Man of the Year banquet than Spencer Haywood, who sported a 6-foot-8 frame and a 26.6 points per game scoring average. Denied the award in 1971 when the Colellas scored an upset victory, Haywood figured to win over a field that included two Olympians, two women and a couple of fringe candidates, sailor Alan Holt and handball virtuoso Gordon Pfeiffer, a two-time (1971-72) U.S. singles champion.

Susan Corrock, one of the Olympians, earned a bronze medal at the 1972 Games in Sapporo, Japan. The other, Sugar Ray Seales, was the only American fighter to win a gold medal in the Munich Games.

The other woman, Kathy Walsh, won the first of what would become four training titles at Longacres, the local thoroughbred oval (see Wayback Machine: Joe Gottstein’s Racing Revival).

MOY voters also could have voted for Calvin Jones, the All-Coast defensive back from the University of Washington; Jerry Grant, the first USAC driver to exceed 200 mph, and Dave Hamilton, an Edmonds native who had just finished his rookie year with the Oakland Athletics.

But most everyone believed Haywood, a first-team, All-NBA selection and a man who had won a Supreme Court case against the NBA that had the net result of allowing college underclassmen into the league, stood above the MOY field.

He didn’t.

The accolade instead went to Tom Gorman, a three-time state champion tennis player at Seattle Prep, an All-American at Seattle University and still early in a professional career of residing among the top 10 singles players in the U.S.

Gorman, the first tennis player named Man of the Year, ultimately enjoyed a 12-year career (1969-80) on the professional tour, where he had notable success in singles and doubles, achieving his best rankings in 1971 (No. 8 in the world), No. 10 in 1974, and No. 2 in the U.S. in 1971.

The year before winning Man of the Year, Gorman scored the biggest victory of his career, a 9-7, 8-6, 6-3 victory over four-time champion and No. 1 seed Rod Laver in the Wimbledon quarterfinals.

Two months before winning, he reached the U.S. Open semifinals. And a month earlier, he had been a member of the victorious U.S. Davis Cup team.

One year after winning, Gorman reached the semifinal round of the French Open by defeating Laver, Jimmy Connors and Jan Kodes.

Gorman worked as U.S. Davis Cup Captain in 1990 and 1992 after having already served twice as head coach of the U.S. Olympic team (1988, Seoul; 1992 Barcelona).

Gorman’s final tennis act in Seattle: In 1977-79, he performed as player-coach of the Seattle Cascades, the city’s entry in short-lived World Team Tennis (see Wayback Machine: Tom Gorman And The Cascades).

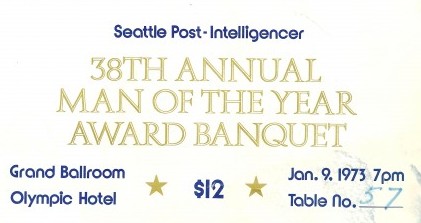

1973 / BILL FENTON, Softball

1973 / SPENCER HAYWOOD, Basketball

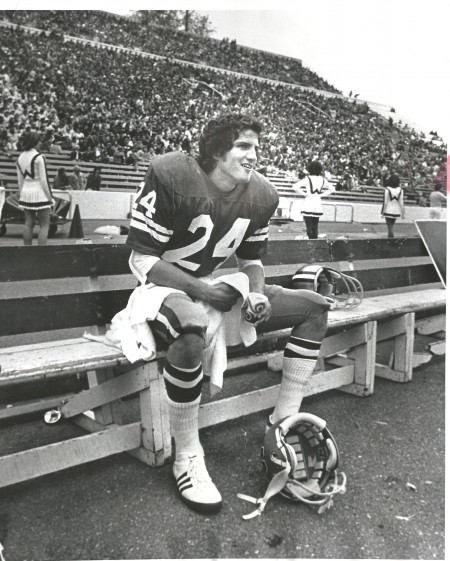

1973 / CALVIN JONES, Football

Willard (Bill) Fenton arrived at the 1973 Man of the Year banquet packing a portfolio of achievements. He was athletic director at Seattle University, an assistant manager at the Washington Athletic Club, and had received national attention for having managed a spate of regional championship fastpitch softball teams sponsored by Federal Old Line Insurance, Pay ‘N Pak and Mead-Samuels Realtors.

By 1970, Fenton’s various teams were well en route to 1,200 wins, under his direction, and Fenton had pretty much punched his ticket into the USA Softball Hall of Fame.

Felton’s place at the Man of the Year head table resulted from his Pay N Pak team finishing sixth in the 1973 national fastpitch tournament and, more important, the role had played in helping secure a future national fastpitch tournament for Seattle.

For all of that, nobody expected that Fenton would be named Man of the Year until banquet founder Royal Brougham announced, to the shock of the Olympic Hotel audience, that Fenton won.

Nobody could quite believe it, not with the likes of Spencer Haywood, popular heavyweight Boone Kirkman, former Garfield baseball star Bill North, and world record holder Jo Harshbarger of the Lake Washington Swim Club reposing at the head table.

As soon as Brougham disclosed Fenton as the winner, a Brougham aide pulled aside the 77-year-old P-I sports columnist, telling “Your Old Neighbor,” as Brougham liked to refer to himself, that he hadn’t quite gotten it right.

So Brougham went before the Olympic Hotel’s 700-person crowd again and announced that, lo and behold, there had actually been a tie vote, UW All-Coast defensive back Calvin Jones having deadlocked with Fenton.

A few minutes later, after Brougham had received another off-stage talking to, he addressed the audience a third time, blurting, according to witnesses, ”We’ve got a three-way tie!”

And suddenly, Fenton, Jones and Haywood were all Man of the Year winners, marking the first time in MOY history that the voting had ended in a three-way tie (the controversial, three-way tie became the impetus for a MOY format change: The job of picking the winner was taken away from Brougham’s hand-picked tribunal and turned over to those in the audience).

If the vote had ended in a four-way tie, or even a five-way tie, justice would have been served. While Haywood, a three-time MOY finalist, made another NBA All-Star team while averaging a career-high 29 point per game, and while Jones was a first-team Associated Press All-American, track and field star Patty Johnson, for example, sported a resume in her sport at least as impressive as Haywood and Jones had in theirs.

Johnson was the fastest runner at Bryn Mawr Elementary school as a kid. At 15, she joined Renton’s AAU Angels Track Club. At 18, after placing second in the U.S. Trials, she found herself running the 80-meter hurdles in the Mexico City Olympics (finished fourth in the final).

Johnson went on to win a gold medal in the 110 hurdles at the 1971 Pan American Games (Cali, Colombia) and made her second Olympic team in 1972. Only injuries prevented her from making a third Olympic team, in 1976.

Patty Johnson also holds the distinction of being the first woman awarded an athletic scholarship by USC. She won two national hurdles championships while competing for the Trojans (1977-78).

Haywood played for the Sonics through 1975, when they traded him to New York, where he didn’t enjoy nearly the success that hed had in Seattle. After leaving Washington, Cal Jones played four seasons with the Denver Broncos.

Of the three co-winners, Fenton actually had the most intriguing career.

At Seattle U., he worked his way up from graduate manager to freshman basketball coach. Then he became the school’s golf coordinator and athletic coach.

At the Washington Athletic Club, he held several positions, including director of athletics. And as a fastpitch manager, Fenton was accomplished enough that, three years after his Man of the Year award, he entered the National Softball Hall of Fame, the first manager selected from the Pacific Northwest.

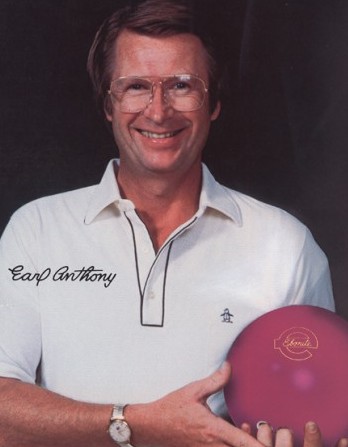

1974 / EARL ANTHONY, Bowling

Earl Anthony established a Professional Bowling Association record in 1974 by becoming the first tour player to win $100,000 in a season. Anthony also won seven PBA tournaments, but no bowler had ever won Man of the Year, not even the great Johnny Guenther, four times a finalist, never a winner.

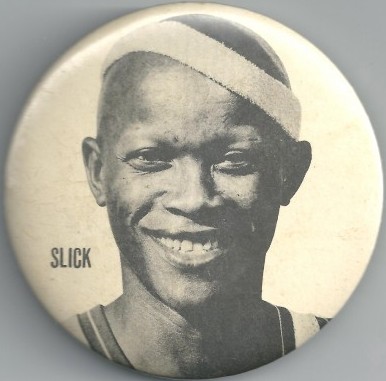

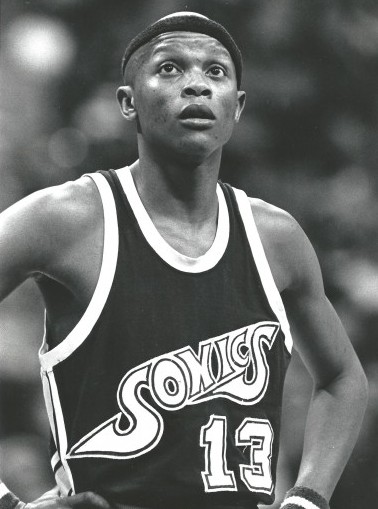

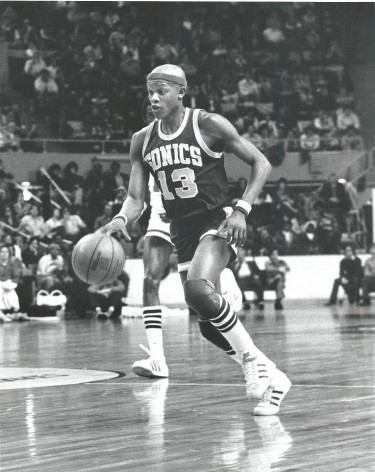

Anthony’s stiffest competition on the ballot came from UW quarterback Denny Fitzpatrick, football player Terry Metcalf, nominated for the first time since 1971, and Slick Watts of the Sonics, making his first ballot showing.

Fitzpatrick, who split time with Chris Rowland, had earned a spot at the head table largely on the basis of a 249-yard rushing performance against Washington State, the third-highest single-game total in UW history, and the best ever posted by a quarterback.

Metcalf, another superb athletic product from Franklin High and a member of the St. Louis Cardinals, made his second Pro Bowl after dazzling as a punt (340 yards) and kick (623 yards) returner. His 31.2-yard kickoff return average, bolstered by a 94-yard TD against Cleveland, led in the league.

Watts, the headband-bedecked SuperSonics guard, was the club’s most popular star, a result of his relentless hustle, not to mention the fact that he ranked among league leaders in assists (6.1) and steals (2.3).

But in 1974, ballot markers determined Earl Anthony was the man.

Anthony wanted to become a major league pitcher. In 1960, at 20, he accepted a $35,000 signing bonus from the Baltimore Orioles. But on the first day of spring training, Anthony tore the rotator cuff in his pitching arm and his baseball career ended.

A year later, Anthony accepted a job as a forklift operator for a Tacoma grocery store chain, and eventually joined the company’s bowling team. He turned professional in 1963, entered seven PBA tournaments and didn’t win a dime in any.

After a six-year hiatus, Anthony, eventually nicknamed ”Square Earl” and “The Machine,” rejoined the PBA in 1970, won his first tournament, and went on to become the greatest and richest bowler in the history of the PBA Tour, eclipsing the great Dick Weber.

Named the ”Greatest Bowler Ever” by the American Bowling Congress (received three times as many votes as Weber), Anthony died Aug. 14, 2001 of injuries he sustained after falling down a flight of stairs at a friend’s home in New Berlin, WI.

1975 / MARV HARSHMAN, Basketball

No individual on the 1975 Man of the Year ballot had compiled a more impressive list of athletic achievements than Earl Averill, by then a 73-year-old former six-time major league All-Star with the Cleveland Indians, who hit .318 over 13 seasons of distinction.

Averill (see Wayback Machine: The Earl And Pearl Of Snohomish) found his way onto the ballot owing to the fact he was the first native of the state of Washington selected for induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY.

Royal Brougham’s selection board also issued head-table invitations to boxer Davey Armstrong, a gold medalist at the Pan American Games; Sonics star Slick Watts, and golfer Don Bies, who had won the $40,000 Sammy Davis Jr. Greater Hartford Open

In addition, hydroplane driver Billy Schumacher, returned to the ballot for the third time, and Al Burleson, whose 93-yard, fourth-quarter interception return for a touchdown in the Apple Cup had provided impetus for Washington’s wild, 28-27 win over Washington State, made it for the first time.

The only coaches on the ballot: Seattle Pacific’s Cliff McCrath, whose Falcons finished runner-up in the NCAA Division II soccer tournament, and Marv Harshman, who produced a 16-10 record in his fourth year as head basketball coach at Washington. Ignoring Averill et al, voters opted for Harshman in a close vote.

Other than coaching his fourth consecutive winning season at UW, Harshman’s most notable 1975 achievement was leading the USA basketball team, featuring Robert Parrish, Otis Birdsong, Ernie Grunfeld and Leon Douglas, to a gold medal at the Pan American Games in Mexico City. Under Harshman’s guidance, the USA averaged 98.1 points per game in compiling a 9-0 record.

Had Harshman been eligible (the Post-Intelligencer abandoned the infrequent practice of returning former winners to the head table), he could have won again in any number of years.

Three of his future teams (1976, 1984, 1985) made the NCAA Tournament field. Two others (1980, 1982) played in the NIT. Four of his clubs won 20 or more games.

By the time Harshman retired (1985), he had coached in 1,090 games, the ninth-highest total in NCAA history, and won 642 games over 13 years at Pacific Lutheran (1945-58), 13 more at Washington State (1958-71) and 14 at Washington (1972-85), and helped more than 500 athletes enhance their skills.

After a career in which Harshman was Pac-8 Coach of the Year (1976) and Pac-10 Coach of the Year (1982, 1984), the Naismith Hall of Fame wasted no time inducting him, welcoming him aboard just months after he coached his final college game.

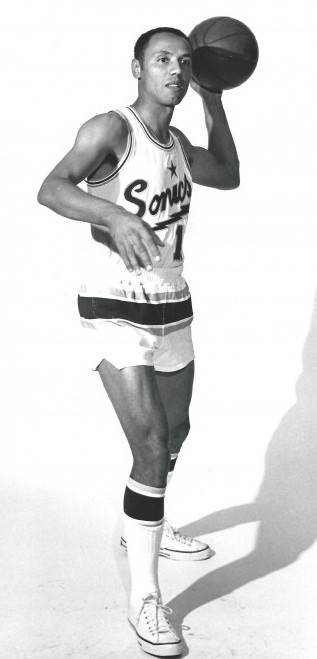

1976 / SLICK WATTS, Basketball

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer pulled a surprise in 1976, the last year Brougham’s “little clambake” operated under the name of Man of the Year. With reader input, it nominated an active, Washington State Cougar athlete for the award. Never had this happened, and it would happen only once more in the 1970s.

The tribunal had good reason to summon affable Jack Thompson to the head table. An Evergreen High grad, Thompson set Pac-8 records for passing yards (2,762) and touchdown passes (20), and was named first-team All-Coast and All-Pac-8. In his most recent game, he established an Apple Cup record with five TD passes against the Huskies.

He also carried one of the most catchy sports monikers in Pacific Northwest history: ”The Throwin Samoan.”

But in a field that included Sounders goalkeeper Tony Chursky, UW nose guard Charles Jackson, U.S. Men’s Amateur Champion golfer Bill Sander, and AIWA long jump winner Sherron Walker of Seattle Pacific, a Sonic, Slick Watts, walked off with the top prize, the first member of the franchise to win it solo (Haywood was been a co-winner in 1973).

And about time: So popular was Watts that he served as Grand Marshall of the annual Seafair Torchlight Parade twice.

What made Watts’ Man of the Year award memorable was the statistical support he gave it. During the 1975-76 season, Watts was the first player in NBA history to lead the league in assists (8.1) and steals (3.2) in the same year.

Watts could have averaged half those numbers and still won Man of the Year.

No Sonic endeared himself more to Seattles sporting citizenry than Watts, who came to the franchise as an undrafted free agent and managed, within five years, to parlay an effervescent personality, a bald head encircled with a distinctive headband, and remarkable hustle, into the height of popularity.

Watts ultimately left Seattle via trade when coach Lenny Wilkens determined that Watts didn’t fit into the system he developed.

Ironically, the Sonics enjoyed their greatest success immediately after swapping Watts to New Orleans — an NBA Finals appearance in 1978 and a title in 1979.

Weeks before the Sonics won the championship in a stirring Game 6 against the Washington Bullets in the nation’s capital, Watts played his final NBA game at age 27.

1977 / WARREN MOON, Football

Nominees for the 1977 Star of the Year award included a future member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the world middleweight boxing champion, a future Olympic gold medalist and the first animal to make the ballot since Ace the Wonder Dog, a black Labrador retriever, was included on the slate in 1952 (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year (1950-59).

This was no ordinary animal. Seattle Slew, owned by White Swan, WA.’s Karen and Mickey Taylor, who made a bargain for the athletic ages when they purchased the colt for $17,500, won thoroughbred racing’s Triple Crown.

Not only was Seattle Slew the 10th to accomplish this feat, and the first since Secretariat in 1973, he was the first to do so undefeated.

Given a vote for the first time in the event’s history, banquet attendees couldn’t see their way clear to go for a colt, even one as good as Slew, instead naming University of Washington quarterback Warren Moon the winner, hardly a surprise.

With only one exception, every time UW reached a Rose Bowl, a Husky representative claimed the ensuing Man/Star of the Year award (Jim McCurdy 1943 season, ‘44 Rose Bowl; Jim Owens, 1959 season, ’60 Rose Bowl); Don McKeta (1960 season, ‘61 Rose Bowl; Rick Redman, 1963 season, ’64 Rose Bowl).

The only time in banquet history that a UW representative did not win following a Husky Rose Bowl appearance: 1936. That year, the Huskies contested Pittsburgh in Pasadena, but Washington crew coach Al Ulbrickson won the Man of the Year award (see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year: 1935-49) after leading the Huskies to a huge upset in the Berlin Olympic Games.

In addition to beating a Triple Crown winner, Moon edged middleweight champion Sugar Ray Seales, on the ballot for the first time since 1972; sailor Carl Buchan, who would a win a Flying Dutchman gold at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics; and UW crew coach Dick Erickson, whose varsity eight had scored one of the biggest wins in school history by capturing the Grand Challenge at the Henley Royal Regatta on the Thames.

In the span of a year, Moon’s UW career took a delightful 180. Booed relentlessly in his early years by a bloc of fans who thought Chris Rowland should have been the quarterback, and by another bloc uncomfortable with coach Don James playing a black quarterback, Moon blossomed into an all-conference player, most notably starting with Washington’s game at Oregon Oct. 8, 1977.

Heading into that game, the Huskies had a 1-3 record and seemed an unlikely candidate for recovery. But Moon engineered a 54-0 victory – the pivotal win during James’ tenure at Washington — that sparked a turnaround for the Huskies, who romped through the rest of their Pac-8 schedule with only a single loss (to UCLA) until Nov. 12, when UW hosted USC.

Moon provided the biggest play of the day, turning a delayed draw into a 71-yard touchdown run that brought the Husky Stadium throng to its feet, cheering Moon for the first time in his career as a galloped through the Trojans.

Six weeks later, Moon earned Rose Bowl MVP honors in Washington’s 27-20 victory over Michigan, launching a career that would end with Moon’s induction in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2008.

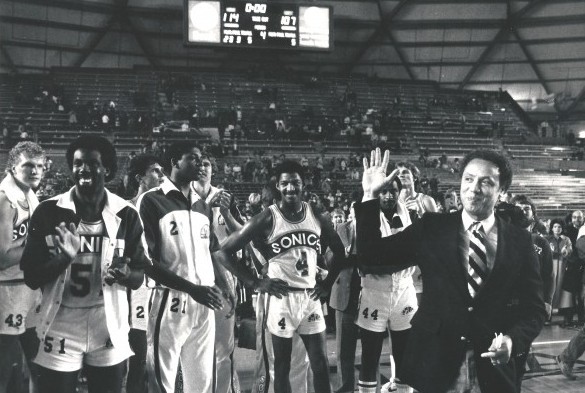

1978 / LENNY WILKENS, Basketball

Lenny Wilkens first appeared on a Man of the Year ballot in 1969, losing to Tommy Harper of the expansion Seattle Pilots. Wilkens made the finals again in 1970, when Doris Brown of Seattle Pacific became the fifth woman to win the award.

Traded by Seattle to Cleveland in an unpopular swap for Butch Beard Aug. 23, 1972, Wilkens was missing from Seattle since. After retiring in 1975, Wilkens went to Portland as the Trail Blazers head coach, spending three seasons there.

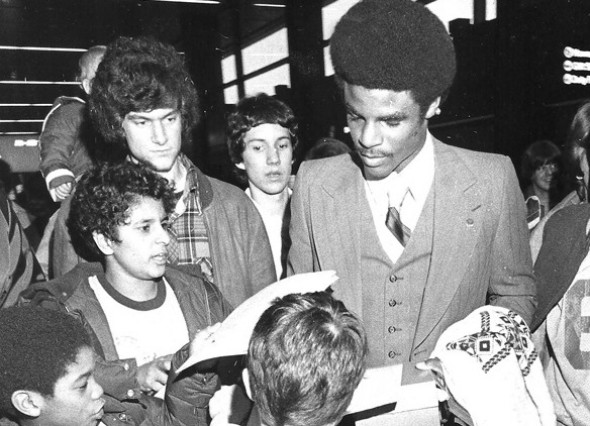

At the beginning of the 1977-78 season, Wilkens returned to the Sonics as director of player personnel. When, under the direction of head coach Bob Hopkins, the Sonics got off to a 5-17 start, owner Sam Schulman fired Hopkins and elevated Wilkens.

Six months later, Wilkens had the Sonics in the NBA championship series, their first, opposite Dick Motta’s Washington Bullets. Although Seattle lost in seven games, its run through the postseason so exhilarated the team’s fans that Wilkens easily prevailed in Star of the Year voting over a slate that included predictable Seahawks (Jim Zorn), Mariners (Leon Roberts) and UW football (Joe Steele) nominees, plus Washington State’s Jack Thompson for a second time, and two athletes, by the simple dint of what they did, who never received sufficient recognition.

Scott Nielson arrived at UW in 1976 from New Westminster, B.C., intent on pursuing a career in medicine.

As Nielson plowed through his studies, he joined Washington’s track team, specializing in the hammer and 35-pound weight throw.

Over the next four years, Nielson won four NCAA titles in the hammer and three NCAA Indoor crowns in the weight throw, his individual total tying the NCAA record first set by an Oregon legend, Steve Prefontaine.

Unfortunately for Nielson, he labored in too much obscurity to knock off Wilkens in a Star of the Year popularity contest.

Same with mountaineer Jim Wickwire, who was nominated after he and climbing partner Louis Reichardt became the first two Americans to successfully ascend the Himalayan peak K-2, the world’s second-tallest mountain (Americans had been attempting to reach the top of that mountain for more than 40 years). They reached the summit Sept. 6, 1978. During his career, Wickwire also pioneered several major northside routes on Mount Rainier, climbed McKinley in Alaska and major peaks in Europe and South America.

1979 / JOE STEELE, UW Football

Only eight individuals comprised the 1979 Star of the Year slate and, given the history of the program’s voting, only three had a realistic chance of winning, Dennis Johnson of the SuperSonics, Steve Largent of the Seahawks, and Joe Steele, Washington’s all-time leading rusher.

Most suspected Johnson would win. He made his first NBA All-Star team in 1979 and, more significantly, was voted MVP of the NBA Finals the previous June, when Seattle won the league championship.

In the title series, Johnson more than redeemed himself for an uncharacteristic 0-for-14 clank in Game 7 of the 1978 NBA Finals, when Seattle lost an opportunity to win the title on its home court.

Not yet the civic icon he would become, Largent set a franchise record with 71 receptions, produced the first of eight 1,000-yard receiving season (1,168) and earned the first of seven Pro Bowl invitations.

Impressive as the 24-year-old Largent was, Star of the Year voters couldn’t ignore the fact that Steele had conquered history. The previous fall, Steele had become the first back in UW football history to rush for 3,000 yards in a career, erasing a school record that Hugh McElhenny had claimed for 28 years (see Wayback Machines: Hugh McElhenny And The Kings and Hugh McElhennys 100-Yard Punt Return).

Largent entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1995, his first year of eligibility. Johnson, who won three NBA championship rings with the Boston Celtics after leaving Seattle, belatedly went into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2010.

Steele never played in a game after Oct. 27, 1979, the day he tore up a knee against UCLA. That may have factored into voters’ thinking: When they cast their ballots, Star of the Year goers pretty much knew they had seen the last of McElhenny’s statistical vanquisher.

ALSO SEE

Man of the Year Winners (1935-76)

Sports Star of the Year Winners (1977-2011)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year (1935-49)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year (1950-59)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of the Year (1960-69)

———————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

———————————————-

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. The top-priced ticket includes admission to the show and the reception where complimentary beverages, including beer and wine, and heavy appetizers will be provided. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. The top-priced ticket includes admission to the show and the reception where complimentary beverages, including beer and wine, and heavy appetizers will be provided. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.

3 Comments

David/Steve. Good stuff. Where’s that picture taken at the top of Wilkens waving? Looks like it could be the Tacoma Dome. In that case it’d be, what, ’82-’83 at the earliest? The Sonics must have played exhibition games there when it was relatively new…

David and Steve – It’s been a few months since I’ve said so, but thanks for the

Wayback Machine. Good writing and compelling content. I’m grateful for the read.