By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

A few days before Christmas, 1963, Fred Hutchinson, at his home on Anna Marie Island (a spit of sand off Bradenton, FL. in the Gulf of Mexico), noticed small lumps and soreness on his neck and chest. Not overly concerned, Hutchinson waited a week before flying to Seattle to consult with his brother, Bill Hutchinson, a prominent physician and cancer researcher, who performed a biopsy on New Years Eve.

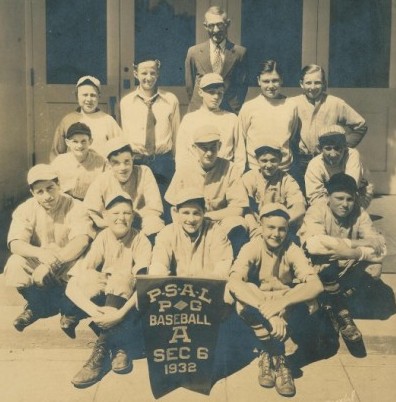

Ten years older than Fred and once captain of the University of Washington baseball team (1931) under Tubby Graves, Dr. Hutchinson delivered an unequivocal diagnosis: The 44-year-old Cincinnati Reds manager, who had smoked three packs of cigarettes a day since his four-year Navy hitch ended two decades earlier, had inoperable lung cancer. Dr. Hutchinson informed his brother that he had no more than a year to live.

Fred Hutchinson immediately sought out childhood friend and former Franklin High teammate Dewey Soriano and asked Soriano to set up a press conference. Soriano arranged it for Jan. 3 — eight days prior to the first Surgeon Generals Report on Smoking and Cancer — at his office.

When a half a dozen Seattle sports writers arrived to hear what Hutchinson had to say, Hutchinson not only shocked them with the disclosure of his cancer diagnosis (the news made headlines across the country), but with the clinical, almost unemotional manner in which he discussed the horrendous news he had received.

This is a hell of a Christmas present, Hutchinson said. Its a very active cancer of the right lung.

“Brother Bill told me the biopsy showed malignant tissue in the right lung, apparently in the early stages, but very active.

But they (his doctors) think they caught it early. After about two months of treatment, through late February, I will be able to go to spring training as far as I know.

Asked by one sports writer how he felt, Hutchinson replied, Its like having the rug jerked out from under you. Ive been feeling fine. My weight is up about 220.

“But I have no knowledge of what to expect. Theres nothing I can do. Its either one way or the other. Naturally, with a thing like this, youre bound to be concerned. But you know youre not alone in it. Lots of others have gone through it. I think I can, too.

Hutchinson began radiation treatments at the Tumor Institute at Swedish Hospital, where he came to a decision that would define him forever: He would not let on to anyone outside his family, especially his ballclub, just how serious his cancer was. In fact, he would tell the Reds and Cincinnati media that as a result of treatments, he had been issued a clean bill of health.

From the late winter of 1964 until early summer, Hutchinson maintained an upbeat façade, never letting on anything was wrong.

But as the Reds moved into pennant contention in mid-summer, the effects of Hutchinsons cancer weight loss, emaciation — became obvious for all to see.

After watching Hutchinson silently battle his disease, Bill Gleason of the Chicago American wrote, I have a hunch that God sends cancer only to those who can handle it, those like Hutch, who, in their handling of it, ennoble us all.”

By late July, Hutchinsons condition had deteriorated so much that he could no longer travel with the Reds. On Aug. 12, Hutchinsons 45th birthday, the Reds, sensing the inevitable, saluted Hutchinson in a ceremony at Crosley Field.

When Hutchinson addressed the 18,000 fans in attendance, he said, echoing Lou Gehrig, What a lucky man I am.

The following day, Hutchinson officially took a leave of absence and returned to Anna Marie Island. It was a leave from which Hutchinson would never return.

The same month Hutchinson bid adieu to baseball, he granted an as told to interview, highly popular in the day, to Al Hirschberg, which True magazine (also highly popular in the day) published under the headline: “How I Live with Cancer.” In the nearly 6,000-word article, which had Hutchinson’s byline, Hutchinson described how he coped with a death sentence.

If I was going to die, worrying wouldn’t save me, Hutchinson told Hirschberg. And if I was going to live, worrying was a waste of time. One thing was sure. I wasn’t going to worry myself to death.”

Hutchinson received $1,000 from True for consenting to the as told to interview, which he donated to a cancer research fund.

Over the course of his time in the majors as a player and manager (1939-64), Hutchinson made dozens of friends, none closer than Bob Prince, Jim Enright and Ritter Collett, who were so moved by Hutchinsons plight, and especially his character and grace, that they decided to take action.

A broadcaster, Prince called Pittsburgh Pirates games on the radio for 28 years. Long after his association with Hutchinson, Enright, a Chicago sports writer and basketball referee, wrote the official history of Illinois high school basketball in which he introduced March Madness into popular vocabulary (Enrights 1977 book title: March Madness: The Story of High School Basketball in Illinois.)

Collett, sports editor of the Dayton Journal Herald, wound up covering every World Series for his newspaper from 1946-90. He won the 1991 J.G. Taylor Spink Award.

Prince took the lead, convincing Pittsburgh-based corporations U.S. Steel, Alcoa and PPG to provide raw materials used in the construction of an award that would bear Hutchinsons name, honor his memory, and be presented annually to a major league player who best exemplified the honor, courage and dedication exhibited by Hutchinson.

During spring training 1966, in a ceremony in Florida, Prince and Baseball Commissioner William Eckert presented the first Hutch Award to Mickey Mantle, citing the “tenacious manner” in which the Yankees center fielder had battled injuries for much of his career. Tenacity not only applied to Mantle, but to Hutchinson, probably his principal asset, in sports and in life.

Born Aug. 12, 1919, in Seattle, the third son of Dr. Joseph Hutchinson and Nona Burke Hutchinson, Hutchinson first made a name for himself at Emerson and Brighton elementary schools.

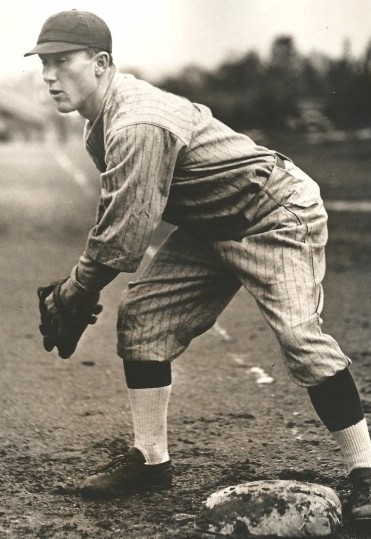

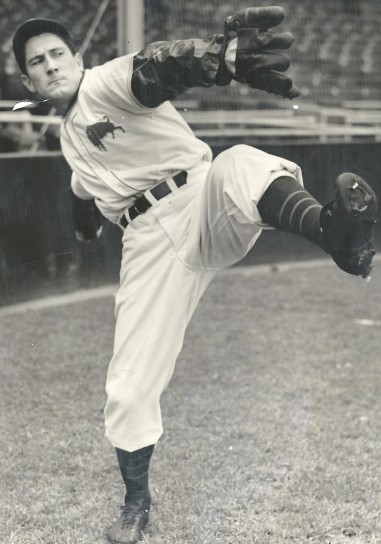

Later, at Franklin High, he became a star pitcher, catcher, outfielder and first baseman. As a pitcher, he posted a 60-2 record and helped Franklin win city championships from 1934-37.

Blessed with big hands, Hutchinson also pitched for American Legion teams Gibson’s Carpet Cleaners and Palace Fish (for Gibsons Carpet Clearners, he once tossed a no-hitter that included 22 strikeouts and a 4-for-5 day at the plate).

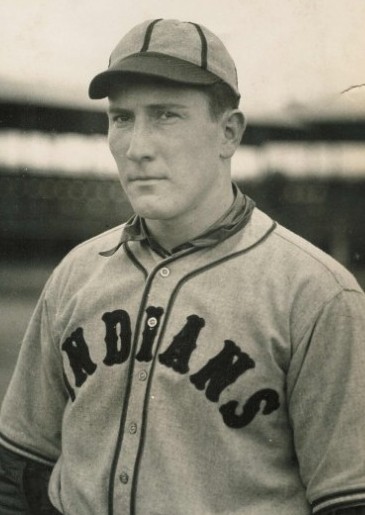

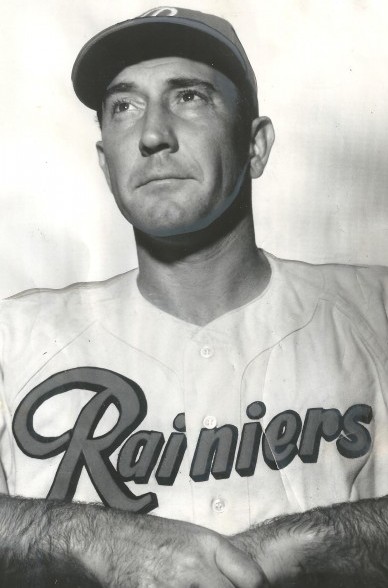

A natural to sign with the AA Seattle Indians (soon to become the Rainiers), Hutchinson did so for $2,500 and 20 percent of any sale to a major league team.

In 1938, Hutchinson became the biggest draw at Emil Sicks new namesake stadium in the Rainier Valley, putting up a season hashed and rehashed (see Wayback Machine: The Rainiers and Pitchers of Beer) for many years.

His storybook stats: 25-7 record, 29 complete games, 2.48 ERA, and his 19th win on his 19th birthday (Aug. 12, 1938), one of the most famous events in Seattle sports history.

Toward the end of 1938, Sick offered Hutchinson to the Yankees, asking for $250,000 and 10 players in compensation. New York owner Col. Jacob Ruppert balked, and Sick ultimately sold his star attraction to the Detroit Tigers for $50,000 and four players, including Jo Jo White, who would help lead the Rainiers to three consecutive (1939-41) PCL pennants.

In the March 11, 1939, issue of Liberty magazine, Seattle Post-Intelligencer columnist Royal Brougham, never one to shy away from hyperbole, wrote that Hutchinson possessed the pitching magic of a Christy Mathewson, and christened him a second Ruth come to judgment.

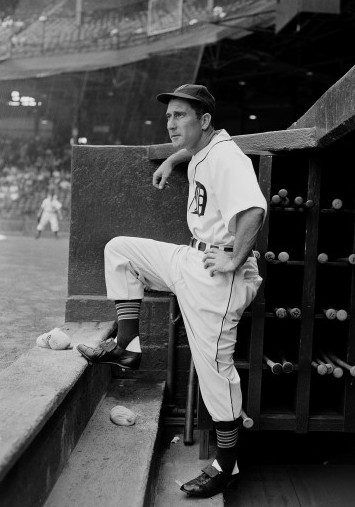

Good as Hutchinson was, he wasnt quite that good. Hutchinson made his major league debut on May 2, 1939, against the Yankees, on the same day Lou Gehrig benched himself, ending his record streak of 2,130 consecutive games played. But Hutchinson didn’t stay long with Detroit, which farmed him to Toledo of the American Association.

Hutchinson didnt show enough at Detroits spring camp in 1940, either, and went to Buffalo of the International League.

A year later, Hutchinson went 26-7 for the Bisons, winning the International League MVP award and proving himself major league ready. But World War II beckoned and Hutchinson spent the next four years (1942-46) in military service.

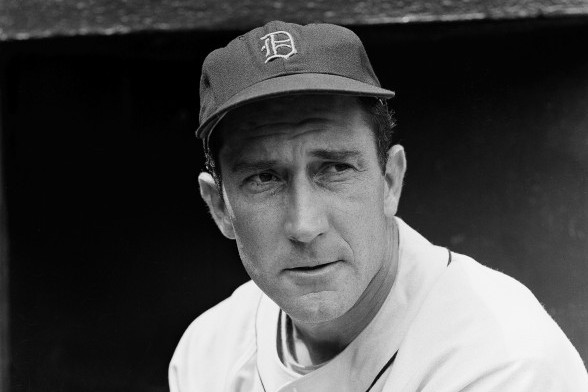

Hutchinson ultimately enjoyed a fine major league career. Joining a Detroit rotation that included Dizzy Trout, Hal Newhouser and Virgil Trucks, Hutchinson won 18 games in 1947 (career high) and 17 in 1950, finishing 95-71 with a 3.73 ERA, 81 complete games, 13 shutouts and one All-Star appearance (1951).

Hutchinson was also one of the best-hitting pitchers of his time. A left-handed batter, he frequently pinch-hit and batted above .300 four times.

While Hutchinson did not put up stunning stats, his career had never been about numbers, as SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) explained:

His most memorable feats were those of character, of an athlete driven to win, of a tempestuous gentleman who embodied every element of that dichotomy.

“And, in the end, of a mortal who lived the final year of his life with the countenance of an everyday hero.

Hutchinson had a legendary determination to win, and his outbursts of temper were both remarkable and frequent media fodder.

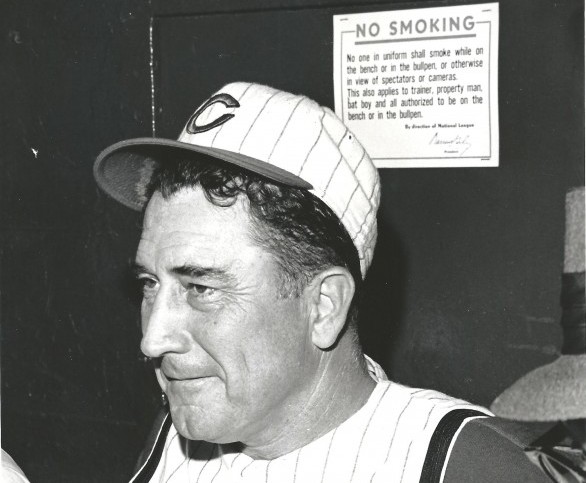

Hutchinsons life-long friend (and former Franklin High teammate) Emmett Watson, one of the great newspaper columnists in Northwest history, described Hutchinson as usually featuring a scowl, his fearsome calling card . . . his face might have been hacked out by an angry sculptor with a dull chisel.

After a bad outing, Watson wrote in a 1957 magazine story, the dozen light bulbs lining the narrow tunnel to the Briggs Stadium (Detroit) clubhouse fell victim to his fists. He unleashed similar fury at other ballparks.

In most men, wrote Georg N. Meyers of the Seattle Times, smashing furniture in monumental fury is a repulsive indignity. The towering rages of Fred Hutchinson are legendary and his intimates accepted them for what they were: A personal and profound protest against defeat in any form.

When, following the 1954 season, the Tigers refused to reward Hutchinson, Detroits manager since 1952, a two-year contract extension, old friend Soriano hired Hutchinson to manage the 1955 Rainiers. Aware of Hutchinsons temper, Soriano installed a heavy punching bag at Sicks Stadium, which featured the cartoon face of an umpire.

Even with that punching bag, he still occasionally made a shambles of the Rainiers quarters, wrote Meyers in the Times. He pitched and managed with a stone face and a soft heart.”

Recalled Yankees catcher Yogi Berra: I always know how Hutch did when we follow Detroit into a town. If we got stools in the dressing room, I know he won. If we got kindling, he lost.”

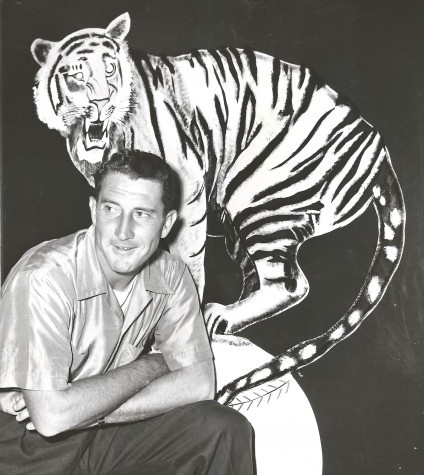

Hutchinson had a couple of nicknames. One was Iceman, the other The Bear. The latter stemmed from a spring training incident in Lakeland, FL., and is best recalled by Virgil Trucks, who pitched for Detroit when Hutchinson did.

“They had a little sideshow circus at the ballpark, and they had a bear there,” Trucks said.

“This bear was staked out by the trainer, but the bear broke the stake and got loose and was coming toward Fred — and Fred just grabbed him by the throat and the neck, and had an arm around his neck.

“He (the bear) probably didn’t weigh any more than Hutch did, but you know bears, they got claws and everything else they can retaliate with. But that didn’t bother Fred.

“The trainer came over and said, ‘Hey, man, you let go of my bear. You gonna kill him.’ He probably would have, but Fred said, ‘You get him away from me. He might kill me, too.’ But he held on to him. That bear couldn’t do nothin’. Oh, he was really strong.”

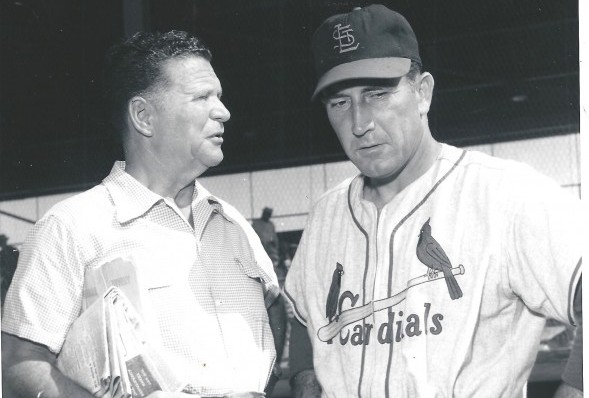

But, as Meyers noted, Hutchinson had a soft heart. Jim Brosnan, who pitched for Hutchinson in both St. Louis and Cincinnati when Hutchinson managed those clubs (Cardinals, 1956-58; Reds, 1960-64) wrote this about Hutchinson in 1959: “Most ballplayers respect Hutch. In fact, many of them admire him, which is even better than liking him.

“He seems to have a tremendous inner power that a player can sense. When Hutch gets a grip on things it doesn’t seem probable that he’s going to lose it. He seldom blows his top at a player, seldom panics in a game, usually lets the players work out of their own troubles if possible.”

Thirty-five years after Hutchinson’s death (3:58 a.m. on Nov. 12, 1964, at Manatee Memorial Hospital in Bradenton, FL.), the Seattle Post-Intelligencer named Hutchinson the city’s Athlete of the 20th Century, an amazing pick considering that that he played and managed in Seattle for slightly more than two years.

“No local athlete has been more revered than Hutch,” wrote Dan Raley. “Hutchinson was a leader, and there was never a question.

“He led people to championships. He led us to tears, sharing his own struggle with cancer in a very public and heroic manner.”

Had Hutchinson not faced the final months of his life with such strength and stoicism, Prince, Enright and Collett might not have been inspired to create the award that bears Hutchinsons name.

In its 47 years, the Hutch Award has been presented to 12 League MVP award winners; 10 Hall of Fame inductees and nine World Series MVPs.

The best thing about the Hutch Award is not that it recognizes athletes who have overcome career-threatening injuries 1976 Hutch winner Tommy John, he of the now-famous namesake surgery, is a prime example — but that it focuses national attention on the great public works of so many athletes who wouldnt receive much without the power and prestige of the Hutch Award.

The 2011 winner, Kansas Citys Billy Butler, who will be presented his award in Seattle this week, is being saluted for his Hit-It-A-Ton campaign, which he launched in 2008 to help feed disadvantaged families in the Kansas City area. Since the campaigns launch, it has generated $200,000 in contributions and provided more than 960 tons of food.

2010 winner Tim Hudson of Atlanta founded the The Hudson Family Foundation in 2009 to help kids and their families ease the financial burdens of critical illnesses.

2007 winner Mike Sweeney had been active in Kansas City’s “Reviving Baseball in the Inner Cities (RBI)” program, which is run through the Boys & Girls Clubs to benefit underprivileged youth.

“If I can bring a glimpse of hope or an ounce of strength to a child fighting adversity, to me that’s more enjoyable than hitting home runs,” Sweeney said after accepting his Hutch Award.

One Mariner received the Hutch Award, Jamie Moyer in 2003, after the Jamie Moyer Foundation, founded in 2000, raised more than $3 million for the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research, LifeCenter Northwest Donor Network, Northwest Harvest, the Susan G. Komen Foundation, Hospice of Snohomish County, and numerous other charities around the country.

“Jamie is amazing,” said Tori Griffith, former director of guilds and special events at Fred Hutchinson. “Not only is he an exceptional pitcher with talent that continues to unfold year after year, he is a also an incredibly kindhearted individual whose compassion touches the lives of many.

“Fred Hutchinson was known for his character, courage, and determination. I cannot think of a more worthy Hutch Award recipient than Jamie Moyer.”

The Hutch Award is still presented to athletes who have overcome major medical issues.

In August, 2006, Jon Lester, a Bellarmine Prep graduate, was diagnosed with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, after leaving the Red Sox while they were in Seattle because he came down with mysterious back pain.

He was referred to the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, the treatment arm of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. There he underwent six rounds of chemotherapy before recuperating at his parents’ home in Puyallup, WA.

Doctors determined that Lester was free of cancer in December 2006. He rejoined the Red Sox for spring training and pitched again in a major league game on July 23, 2007.

Lester went 16-6 with a 3.21 ERA in 2008 while helping lead Boston to the postseason. He threw the 18th no-hitter in Red Sox history on May 19 against the Kansas City Royals. He received that years Hutch Award.

Stories such as Lesters and the kind of generosity exhibited the likes of Butler, Hudson, Sweeney and Moyer would never have gained national attention without the Hutch Award, one of the most notable winners of which was Craig Biggio in 2005.

Biggio played his entire major league career (1988-07) with the Houston Astros, probably sacrificing millions of dollars he might have made in free agency, primarily so that he could remain close to Houston-based Sunshine Kids, a support organization he founded for children with cancer and their families.

A day after Hutchinson’s burial at Renton’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, Meyers wrote in the Times, The measure of the mark Fred made in the special world he inhabited for 45 years is the respect he commanded far from the community which claimed him with pride and adulation.

“It was won without effort, intent or pretense. Baseballs record books will never capture the image of Fred Hutchinson as a pitcher: It was not how well he threw a ball that characterized him, but how fiercely.

“He represented strength in physique and principle; justice, abhorring indolence, rewarding dilligence; above all courage.

The Baseball Writers Association of America voted Hutchinson its “Most Courageous Athlete” award in 1964, and Sport Magazine named him that year’s Man of the Year.

A few weeks after Hutchinsons death, former Pacific Coast League umpire Dick Phillips wrote a letter to a Seattle newspaper in which he said, Hutch was the only manager I ever knew who instilled in a player and an umpire, through his own great image, the desire to put out just a little more because Hutch was watching. He will live in baseball memories.

And in memories beyond baseball. Bob Prince, Jim Enright and Ritter Collett, by creating the Hutch Award, and Dr. Bill Hutchinson, by opening what became the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center a few months after his younger brother’s death, made certain of that.

List of Hutch Award Winners (1965-11)

——————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

5 Comments

Excellent piece on a truly inspirational man. Thanks.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, thank you, Paul for reading and responding to our latest Wayback Machine!

Excellent piece on a truly inspirational man. Thanks.

Good stuff.Great talking to you today Dave,keep in touch

Sean Walsh

Original Stadium Seats

http://www.originalstadiumseats.com

Good stuff.Great talking to you today Dave,keep in touch

Sean Walsh

Original Stadium Seats

http://www.originalstadiumseats.com