By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

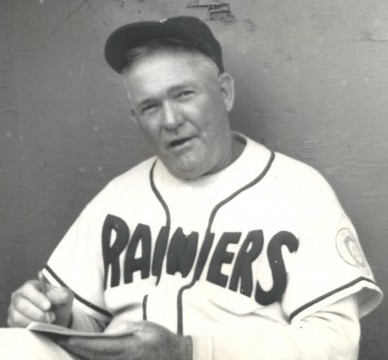

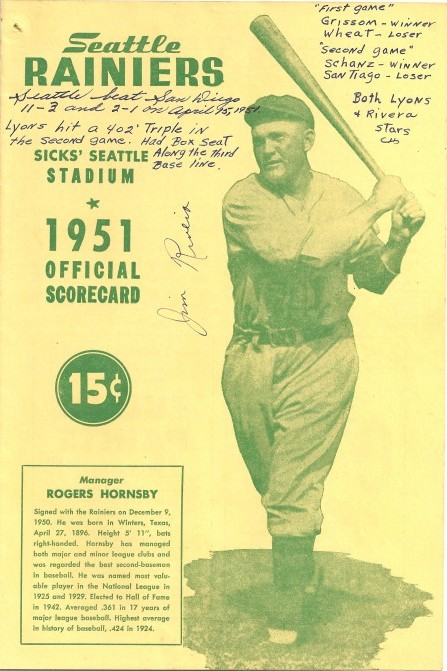

Had Rogers Hornsby, the incoming manager of the Seattle Rainiers, opted to stay away from Puerto Rico in the winter of 1950, and he very nearly did, a significant chapter in Pacific Coast League history never would have unfolded, and a local championship, the last under the Rainiers banner, probably would not have occurred.

“Looking back on it now,” Hornsby told Lenny Anderson of the Seattle Times in the summer of 1951, ”it was probably a whim that I went to Puerto Rico at all.”

A career .358 hitter over 23 major league seasons and the winner of seven batting titles and two Triple Crowns, the famous “Rajah” had been a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame for nearly a decade when the Rainiers made him their manager Nov. 11, 1950, as a replacement for Paul Richards, lured away by the Chicago White Sox.

The Rainiers, in turn, lured Hornsby out of the Yankees farm system, signing him, in the words of Anderson, “sight unseen and by telephone and cablegram.” Club owner Emil Sick (see Wayback Machine: Seattle First Citizen Emil Sick) had given Hornsby, who managed Beaumont to the Texas League pennant, a one-year contract worth a reported $30,000.

At the time, Hornsby ran his own baseball school in Chicago, where he wintered, and had not given the Puerto Rican Winter League much thought until the Rainiers offered him a chance to replace Richards. But after speaking with his predecessor, Hornsby determined that the Rainiers, with 104 losses in 1950, required an extreme makeover.

(Ultimately, Hornsby discarded a number of the Rainiers’ biggest names from the 1950 squad, including pitchers Vern Kindsfather, a 12-game winner, and Guy Fletcher, and most especially, Bill Schuster, a hyperactive shortstop with a comedic routine that Hornsby, an all-business type of guy, couldn’t tolerate.)

Seattle had not had an affiliation with a major league team since its agreement with the Detroit Tigers lapsed in 1948. So Hornsby couldn’t count on a big league team supplying the Rainiers with talent. On the spur of the moment, he decided to manage the Ponce club in Puerto Rico and use the opportunity to also scout for talent for the Rainiers.

A couple of weeks into the Puerto Rican winter league season, after he eyeballed the available talent, Hornsby flew to St. Petersburg, FL., to meet his new Seattle bosses face-to-face: Sick, club VP Torchy Torrance and GM Earl Sheely. They, along with representatives of 23 other clubs, would attend the minor league winter meetings at the Vinoy Park Hotel and participate in a draft of players from the low minors — players in whom major league teams had little immediate interest.

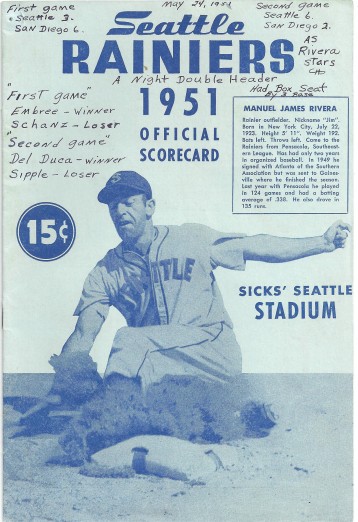

First order of business: Hornsby signed the contract Torrance mailed him and handed it over to Sick. Second order: Hornsby hired Bennie Huffman, a long-time associate, as his lead coach. Then, at Hornsby’s recommendation, the Rainiers used their available draft choices on 28-year-old pitcher Mike Clark, who won 10 games the previous summer for Houston of the Texas League; catcher Joe Montalvo, who played for Shreveport (AA); Wes Hammer, an infielder from AA San Antonio, and a 28-year-old longshot outfielder named Jim Rivera, who never played above the Class B level.

Rivera, with the Caguas team in the Pureto Rican Winter League, not only caught Hornsby’s attention, but New York Giants manager Leo Durocher’s as well. Durocher, on a visit to Puerto Rico, said, ”Now that’s my kind of ballplayer.” To which Hornsby replied, ”That’s any manager’s kind of ballplayer.”

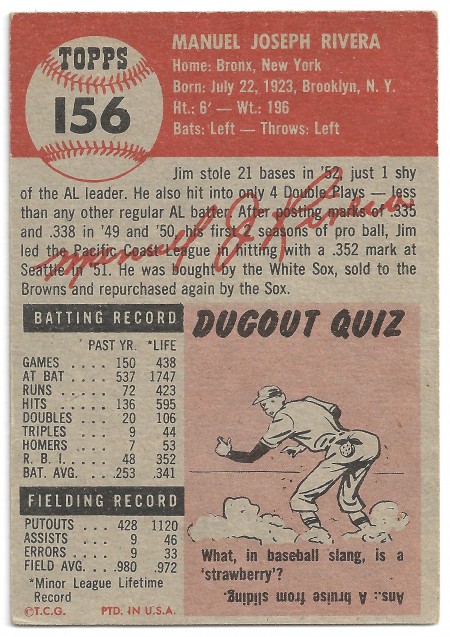

A 6-foot-1, 196-pound left-handed hitter, Rivera played pro ball for two years, for Class D Gainesville (go G-Men!) of the Florida League in 1949 and Class B Pensacola (Southeastern League) in 1950. While Rivera had feasted on low-minors pitching, there was nothing to suggest he could succeed at the AAA level — except Hornsby’s gut instinct.

Only one problem: Hornsby couldn’t be sure the Rainiers would be able employ such an individual. As it turned out, there was good reason why Rivera played two years of professional baseball by age 28.

Born in Brooklyn July 22, 1922, to Puerto Rican immigrants, Manuel Joseph Rivera came from a family of six brothers and five sisters, growing up on the streets of Spanish Harlem. Rivera’s mother passed away when he was six, his father couldn’t care for him, and had no choice but to send him to Saint Dominic’s Orphanage in Blauelt, NY., on the upper Hudson River. Rivera lived there for nearly 10 years, his principal education coming in boxing and baseball.

Rivera left the orphanage at 16 and took odd jobs, mainly in construction, to help support his father and 10 siblings. At 17, he began to box as an amateur in various tournaments around New York. Rivera continued to fight after he joined the Army Air Corps in 1942 — he won the light-heavyweight title of the Third Air Force at Camp Barkley, TX. – and also played on the camp’s baseball team. When Rivera wasn’t boxing or playing baseball, he taught judo. In 1944, Rivera’s life fell into turmoil.

The Army charged Rivera with raping the daughter of an officer. Following a medical examination of the woman, which showed she was still a virgin, the Army reduced the charge to attempted rape. It found Rivera guilty, dishonorably discharged him, and sentenced him to life imprisonment.

Rivera served nearly five years in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, receiving a parole in 1949, in part because of his skills as a baseball player.

The Atlanta pen had a prison team, on which Rivera played, and it engaged in a number of outside games against local competition. Rivera caught the eye of Earl Mann, who owned the city’s professional club, the Crackers. Mann coveted Rivera and worked to help secure his early release. When the parole came through, Rivera had a contract offer awaiting him.

(Sidebar: the aforementioned Paul Richards managed the Crackers from 1938-42, and Joe Schultz, who managed the Seattle Pilots in 1969, skippered the Crackers in 1962.)

The Crackers farmed out Rivera to their Class D affiliate in Gainesville, for which he hit .335 with 142 runs scored and 55 stolen bases. That earned Rivera a promotion in 1950 to Class B Pensacola. The rise in class failed to deter Rivera’s progress: he hit .338, crossed the plate 139 times and knocked in 135 runs as Pensacola won the Southeastern League pennant.

In the 1950 offseason, at the urging of an acquaintance, Rivera joined Puerto Rican team Caguas. He added to his repertoire a head-first belly slide into bases, a tactic that would become a trademark of his game (he made that sliding style fashionable 20 years before Pete Rose).

Hornsby, managing Ponce, developed an immediate infatuation for Rivera and would later say in interviews that Rivera was the only player he would pay to see play. The one-time orphan would be quoted frequently to the effect that Hornsby had adopted him, and was like a step-father.

As VP Torrance explained in his 1988 memoirs, Seattle’s concern over Rivera had to do with his prison background.

“Hornsby and I talked with Mann (Crackers owner) about Jim at a major league meeting we attended in New York,” Torrance wrote. Mann thought Rivera would make a good ball player for somebody, but because of the circumstances (Rivera’s time in prison), there was no way they could use him in Atlanta. We decided to take a chance on him.” Purchase price: $2,500.

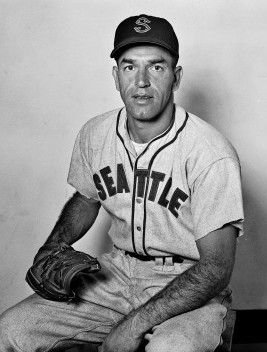

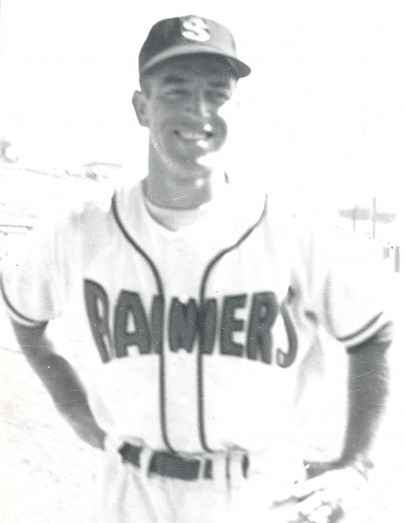

The Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer delivered their first reports on Rivera March 3, 1951, the P-I reporting, “Manuel Jim Rivera, the outfielder from Pensacola, looked like money in the bank today. He whacked the ball as if he had a personal grudge against it. He is extremely fast and has a good arm.”

When Hornsby advised on behalf of drafting Rivera at the winter meetings in St. Petersburg, Anderson wrote in The Times shortly after the start of the 1951 season, “the jump to AAA seemed too great. The concern vanished the moment Rivera picked up a bat in spring training. He could make a bat whistle when he swung it, and he was in shape because of winter ball. He could throw far and hard and run all day. But of course, that was early in the going, and nobody could really believe that an unheralded rookie could come out of B-ball, as Rivera had done, and make the jump to AAA.”

But then the season began with Rivera in center field, and almost immediately he was leading the league in virtually everything but the standing broad jump.

Seattle scribes became enamored with Rivera, even if he did foul the air with his Cuban cigars and chased skirts to all hours. The writers usually found him good for a quote, and he had an engaging personality and immense talent.

“He covers a lot of ground in the outfield and runs the bases in a daring fashion reminiscent of the last (Rainiers) man to wear the big No. 7 — Jo-Jo White (see Wayback Machine: The Rainiers & Pitchers Of Beer). His rousing, headlong sliding is already a thing Seattle fans go to the park to see,” Anderson wrote.

“Most rookies come to camp with traces of trepidation. Not Rivera. That was demonstrated the first week. Jim asked the ball club photographer to give him a print of a certain picture he wanted to mail back home to his dad.”

”Get it quick as you can, will you? Rivera asked the photog. “I might not be here long. I might go to the Yankees.”

Wrote another reporter: ”He runs in the outfield like a deer, on the bases like an express train, and he throws like a rifle.”

Whether at the Rainiers’ request, or simply out of lack of interest in a less intrusive journalistic age, Seattles sporting media — print and broadcast — never probed into Rivera’s penitentiary stint (fat chance of that happening today) during a 1951 season that got off to a slow start for the club, but not for Rivera. Even after reporters became aware of Rivera’s past late in the season, they refused to acknowledge it.

After the first week of the campaign, Rivera sported a batting average of .452. By April 8, he had fashioned a 12-game hitting streak (snapped in a 5-0 loss to the San Francisco Seals).

On April 24, 1951, with the Rainiers still a second-division club, they edged the Hollywood Stars 4-3 in front of 4,838 at Sicks Stadium. Seattle won when Rivera beat out a bunt, took second on an overthrow to first, advanced to third on an infield out and then pulled off a pure steal of home, crossing the plate with a head-first slide.

The next night, also against the Stars, Rivera scored from second on a short fly ball to center by teammate George Vico.

By mid-May, when the Rainiers began gaining ground on Portland and Sacramento, Rivera sat at or near the top of virtually every PCL offensive category, leading Hornsby to tell reporters, “I’d rather watch him play than anybody else. He does everything to beat you. He’ll beat you with his bat. He’ll bunt, drag, or knock the ball out of the park. He’ll beat you with his fielding and throwing, and he’ll steal any base most any time.”

“I want to lead the league in everything I can,” said Rivera.

”Rivera likes to play ball and someday will go to the big leagues,” Hornsby added. “When he learns to hit the change and slow-breaking stuff, he will be ready.”

Also in mid-May, major league scouts, having picked up rumbles about Rivera’s surprisingly outstanding season, began to descend on Seattle, arriving in such droves that general manager Earl Sheely had to cordon off a couple of box-seat sections in order to accommodate them.

For the Rainiers, Rivera represented a major financial opportunity, much like the one that presented itself in 1938 when they traded popular local hero Fred Hutchinson (see Wayback Machine: Hutch — A Man And An Award) to the Detroit Tigers for $50,000 and a nucleus of players who formed the core of three PCL pennant winners from 1939-41.

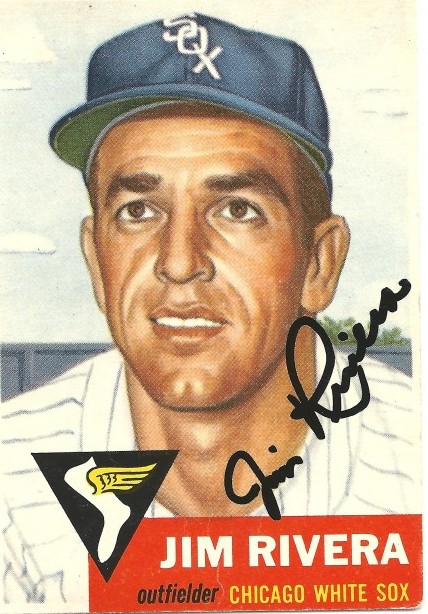

On July 23, the Rainiers received the windfall they sought when the Chicago White Sox purchased Rivera’s contract for $65,000, $62,500 more than the Rainiers spent to acquire him. Under terms of the sale, Rivera would play out the remainder of the PCL season in Seattle, then report to Chicago. Torrance negotiated the deal.

“I had a lot of trouble with Jim, though,” Torrence wrote. ”When other inmates got out of prison and knew that he was making a success of himself in baseball, they began calling on him for money and other favors.

”He actually needed a caretaker when he wasn’t on the field, so I arranged to have Orville Mills, a law partner of Stephen F. Chadwick, the club’s attorney, look after him. Orville stood about 6-foot-5 and weighed 250 pounds, so he was a good choice to protect Jim.

“Things were going pretty well for about a year when I got a call from the Grosvenor House (6th & Wall) saying that Jim was having some kind of trouble in his apartment. Orville and I went right over and found a guy accusing Rivera of taking advantage of a girl who supposedly was the fellow’s wife.

“He was demanding a $500 payoff to let Jim go. It didn’t take us long to find out it was a frame-up, so we got the guy out of town on the afternoon train. When I sold Jim to the White Sox, I told him he should get a bodyguard or somebody to keep him out of trouble. I don’t know if he did it or not. But he was memorable.”

Rivera didn’t slide after his sale to the White Sox. In a three-game series with Hollywood in late August, by which time the Rainiers had moved into first place, he went 9-for-21.

In early September, the Rainiers clinched the regular-season championship by 6 1/2 games over Hollywood, then defeated Los Angeles two out of three and the Stars in five games for the Governor’s Cup, the franchise’s fifth.

Numerous Rainiers put up big years to make the championship happen. Veteran Marv Grissom won 21 games and Hal Brown 16. Wally Judnich hit .329 with a club-leading 21 homers and 102 RBIs. Al Lyons added 20 homers and 94 RBIs. But Rivera dominated the marquee.

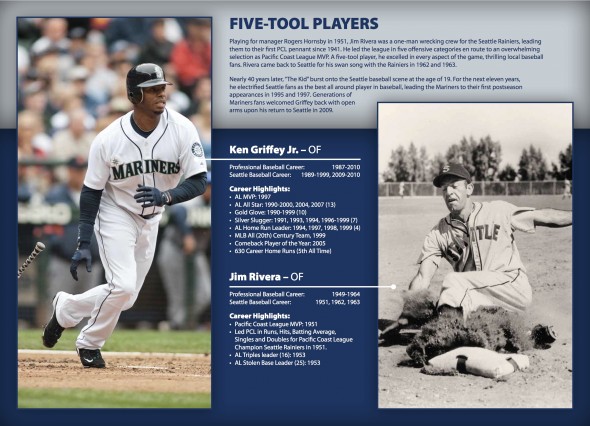

He received 14 of 23 votes from PCL managers and writers, easily winning the league’s Most Valuable Player award, after finishing a season that included a .352 batting average, 231 hits, 40 doubles, 20 home runs, 120 RBIs, 33 stolen bases, a .420 OBP and a .972 OPS. His batting average led the PCL, as did his hits, doubles and stolen base totals.

Sick was so elated with Seattle’s first championship since 1941 that he offered Hornsby a three-year contract, with a raise. Hornsby told Sick he wanted to think about it — he hoped to parlay his success with the Rainiers into a major league job — and motored home to Chicago.

As the days passed, several Seattle sports writers who never warmed to Hornsby started to pressure Sick to go in another direction for a manager.

Those writers didn’t like Hornsby’s overbearing ego or his style, thought him a tyrant — “He smothered everyone with his brutish style,” author Dan Raley wrote in an extensive condemnation of Hornsby in his excellent book “Pitchers Of Beer” — and a few enjoyed jibing him in print.

One even went so far to point out that Hornsby, who played the bulk of his career in St. Louis, had never gone to a movie in his life until The Pride of St. Louis was released.

“The only reason he went, the reporter wrote, “was because someone told Hornsby the movie was about him (actually about Charles Lindbergh).”

Anderson didn’t fall into the anti-Hornsby camp, writing, “He’s brusque and demanding of himself, and of those around him. But this has worked for Seattle baseball.”

When the debate over whether to bring back Hornsby escalated in the newspapers, Sick, according to Torrance, called Hornsby and demanded an immediate answer whether Hornsby would return.

“Okay, if you’ve got to know right now,” Hornsby said, ”I’m not coming.”

Weeks later, Hornsby became the manager of the St. Louis Browns. One of his first acts was to encourage owner Bill Veeck to make a play for Rivera.

“They tried to brush him back in the Coast League and the more they threw at him, the tougher he got,” Hornsby argued. ”He can take care of himself, too. Dont forget, he’s 192 pounds and was a professional prize fighter.

“An infielder named Pavolic got rough with Rivera in Seattle and only two punches were landed. He knocked Pavolic half way to third base and won that argument.”

The deal came down when Veeck sent catcher Sherman Lollar to Chicago in a three-team, eight-player exchange that brought Rivera to the Browns.

Unlike in Seattle, where Rivera’s prison stint went unreported, his arrival in St. Louis prompted a huge stir. Civic and religious groups launched campaigns to have Rivera tossed off the Browns roster and banned from baseball.

The matter finally reached the commissioner’s office, Ford Frick stating, “If the purpose is punishment, then he has already been punished. If the purpose is cure or improvement, then this man has a greater chance to make good being allowed to live as others live.

“Since Rivera came into baseball, his conduct has been beyond question. If he shows that he has not profited by his experience, this office will take action.”

Frick concluded by saying, ”To the best of my knowledge, after making a check of the records, this is the first time a commissioner ever had to make a decision on a morals charge.”

Rivera’s major league debut, for St. Louis, occurred April 15, 1952, and he collected one hit in three at-bats. But Rivera lapsed into a slump and the Browns began a dive in the standings.

When the teams record reached 22-29, the Browns fired Hornsby. Rivera followed him at the end of July when the Browns traded him back to the White Sox.

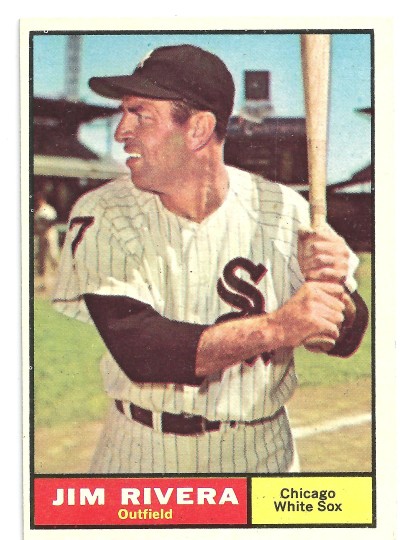

Thus began a 10-year run with the White Sox (1952-61) and Kansas City Athletics (1961), during which Rivera hit .256 with 83 home runs. He led the American League in triples (15) in 1953 and in stolen bases (25) in 1955 (finished second in stolen bases six times).

Toward the end of Rivera’s career, White Sox GM Ed Short said, ”He may not have the fattest batting average, but he gives fans a show with his daredevil running and sliding, his terrific fielding and his clutch hitting.”

On the last day of his first season with the White Sox, Sept. 29, 1952, law enforcement officials entered the team’s clubhouse and arrested Rivera on charges that he had raped Janet Gater, the 22-year-old wife of an Army statistician stationed at the Fifth Army headquarters in Chicago.

Mrs. Gater alleged that Rivers had raped her in her apartment the evening before, adding that Rivera had approached her after she dropped some books while walking her dog.

Rivera admitted having sex with the woman, but argued that his relationship with her had been consensual, and that she had invited him to her apartment. Authorities released Rivera on $3,000 bail, but booked him into felony court the following day.

Rivera insisted on taking a lie detector test, passed it and was released again on a $5,000 bond. He later escaped indictment by a Chicago grand jury.

But Frick placed Rivera on indefinite probation, and told the White Sox they could not trade or sell Rivera for at least a year.

Rivera responded to all this embarrassment by stringing together his best years. His 10 homers, 24 doubles and 16 triples helped the White Sox to 89 wins in 1953, their highest total in more than 30 years. The White Sox did even better in 1954, winning 94 games, as Rivera batted a career-high .286.

It was during the 1954 season that Rivera started to wildly flap his arms as a way of waving other Chicago outfielders off fly balls.

Rivera’s antics inspired John Hoffman of the Chicago Sun-Times to begin calling Rivera “Jungle Jim.” The nickname stuck.

Chicago writers enjoyed Rivera as much as the Seattle writers. For reasons such as this: Once, after hitting a home run to beat the Kansas City Athletics, he strode up to former First Lady Bess Truman, in attendance that day, and said: “I’m sure sorry my homer beat your team, but it was a helluva wallop, eh, Bess?”

On Opening Day 1961 at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C., Rivera strolled up to President Kennedy following the Presidential first pitch and asked for an autograph. Kennedy obliged. But when Rivera saw the President’s signature, he said, ”What’s this? This is just a scribble! I can hardly make it out! You’ll have to do better than this, John.”

Rivera retained enough of his skills that he was able to make a contribution as a 37-year-old pinch-hitter, pinch runner and platoon starter to the 1959 Go Go White Sox that won the American League pennant.

Rivera’s final big baseball moment occurred in that year’s World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers. He started games one, three and four (went 0-for-11), but made his biggest impact in Game Five at the L.A. Coliseum.

After two Dodgers reached base in the seventh inning of a scoreless game, Chicago manager Al Lopez inserted Rivera into right field as a defensive replacement. Charlie Neal of the Dodgers promptly smacked a drive to right-center that looked good for extra bases. But Rivera made an over-the-shoulder catch to preserve a 1-0 lead and the game.

Rivera appeared in only 49 games for the White Sox in 1960-61, and got in 64 more after signing with the Athletics as a free agent. When the Athletics cut him loose at the end of the season, his major league career reached its end.

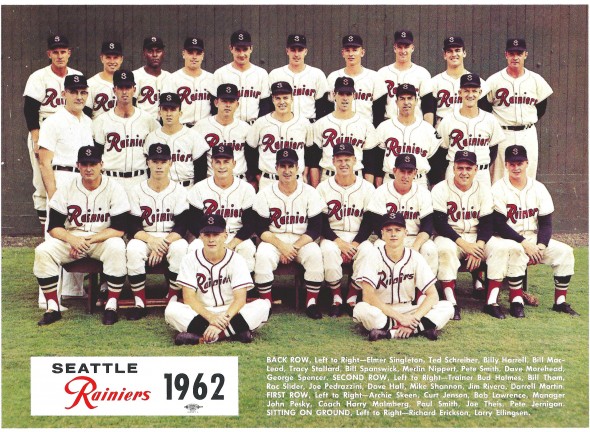

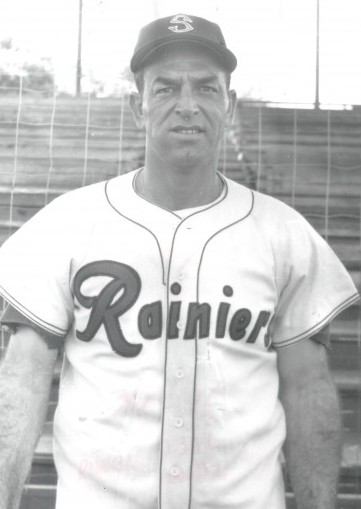

Rivera oddly ended up where his baseball career had really begun, in the Puerto Rican Winter League, but as a manager. A subsequent stint with the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association didn’t last, and by July, 1962, Rivera found himself back in Seattle. He eked out a year with the Rainiers before his unconditional release in June 1963.

Refusing to acknowledge the end, Rivera ventured south and played in the Mexican League in 1963 and 1964. He eventually settled in Port Charlotte, FL., where he operated a restaurant, The Captain’s Cabin, for more than 20 years.

He’s 90 years old now, and is still there.

—————————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

4 Comments

excellent article. what a great read, and what an interesting guy Rivera was.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, thanks for visiting!

excellent article. what a great read, and what an interesting guy Rivera was.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, thanks for visiting!