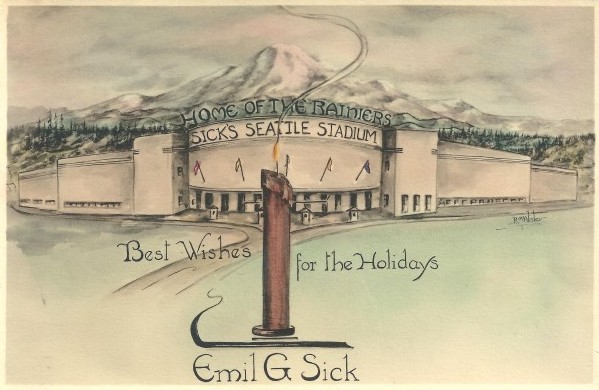

Note: The Seattle Pilots’ one and only MLB season opener in Seattle’s Sicks’ Stadium was April 11, 1969. In the presumably temporary absence of baseball this spring, Sportspress Northwest is re-publishing this March 6, 2012 feature on beer baron Emil Sick, who bought the minor-league Seattle Rainiers in 1937 and privately funded for the team his namesake stadium in 1938, which housed the Pilots and survived until 1979. Let us divert . . .

By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

If all the flattering words used to describe Emil Sick in the aftermath of his Nov. 10, 1964, death could be bumped together in a single volume, the work probably would be fatter than a James Michener novel.

“If you couldn’t work for Emil, you couldn’t work for anybody,” Edo Vanni said after Sick’s graveside service. ”I would have worked for him for nothing.”

“One of the grandest men I have ever known,” added Roscoe C. (Torchy) Torrance, a one-time University of Washington baseball player and life-long civic booster who probably knew as many men as any Seattle man ever has.

“He was almost Prussian in demeanor,” wrote columnist Emmett Watson, who briefly worked for Sick. ”Yet he was unfailingly courteous, genteel, well-spoken, and sensitive to others. We called him Mr. Sick. Everybody called him Mr. Sick.”

In reporting the 70-year-old Sicks death, which resulted from a stroke at Swedish Hospital while convalescing from an operation, The Seattle Times used an interesting word to describe him.

The newspaper oddly, but accurately, selected philanthropist, even though it had its choice of many descriptions more commonly associated with him, and many of which the newspaper itself had used in hundreds of stories about him.

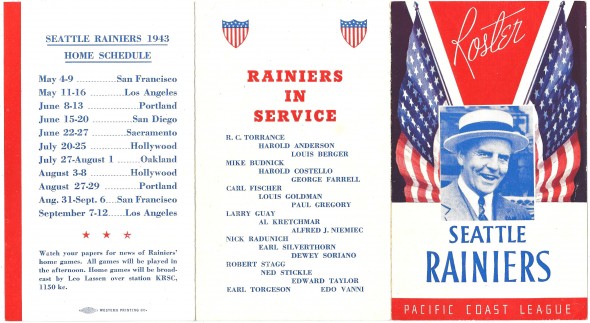

In the thousands of articles published in The Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer between 1933 and 1964 that mentioned Sick, nearly all referenced his role as owner of the Seattle Rainiers Pacific Coast League baseball team (1937-60), and most cited his ownership of Rainier Brewery on Airport Way South.

But only a few focused on Sick’s philanthropy and public good works, which were legion and have tangible legacies today.

”Mr. Sick took special interest in encouraging the careers of young men in his various business enterprises and in other spheres having no connection with his own activities,” The Times editorialized. In many ways, he was a first citizen of this community throughout his working life.

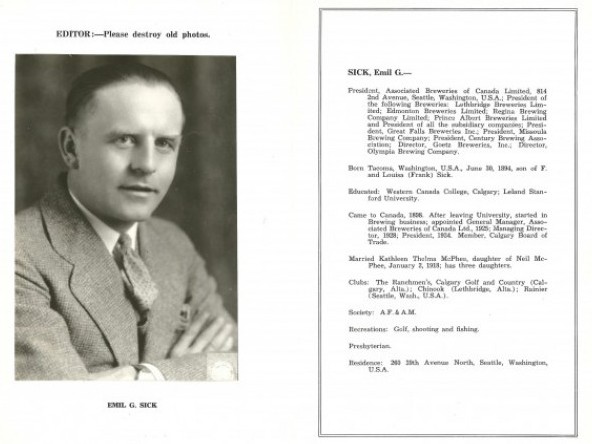

Born June 3, 1894 in Tacoma, son of Canadian brewer Fritz Sick (1859-1945), the creator of Old Style Pilsner, Emil Sick attended Western Canada College in Calgary, and took courses at Stanford University.

After college, Sick worked first as a shipping clerk at his father’s brewery in Lethbridge, Alberta, and later in various roles at his father’s operations in Spokane, Salem, Missoula, Vancouver, B.C., and Prince Albert and Regina, Saskatchewan.

Sick received his first important promotion in 1925 when he became general manager of the Associated Breweries of Canada, LTD. He served as managing director of the company in 1928 and president in 1934, one year after he and his father entered the U.S. market following the repeal of Prohibition.

The Sicks began by acquiring control of breweries in Great Falls and Missoula. Then they established the Goetz Brewery in Spokane. Moving on to Seattle, Fritz and Emil made a deal to lease the old Bay View Brewery at the base of Beacon Hill (Ninth Avenue and Hanford), which was shuttered in 1919 and turned into a feed mill.

On June 7, 1933, the Sicks incorporated the Century Brewing Association and re-named the Bay View plant Century Brewery, modernizing it with a $75,000 investment. A year after leasing the property, the Sicks purchased it.

A year after that, the Sicks made their most important transaction, one that would not only create family wealth and transform Emil Sick into one of Seattle’s most significant citizens, but reshape baseball in the state for decades: They acquired exclusive rights to sell the Rainier brand in Washington and Alaska from the Rainier Brewing Co. of San Francisco.

Eventually, the Sicks produced a variety of beers, including Sicks Select, an alternative to their flagship brand, Rainier. This allowed them the opportunity to offer a premium Seattle beer in lucrative markets beyond Washington and Alaska, principally in San Francisco and Portland.

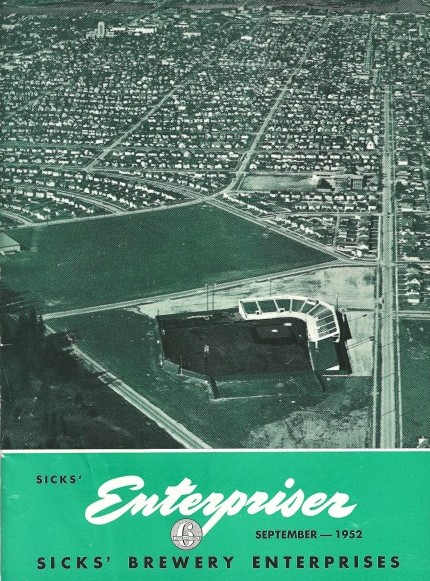

But Rainier beer was the franchise. The immediate popularity of the brand made it possible for the Sicks to move their principal base of operations into a larger plant at 3100 Airport Way S., on the top of which the Sicks installed a huge, red, rotating ”R” neon sign that quickly became a Seattle landmark.

Emil Sick was always lucky, Watson wrote following Sicks death. But he was also good.

Sick and his father had been smart enough to cast their financial fate to one of the few business enterprises not in the tank during the Great Depression: the production and sale of (relatively) cheap beer.

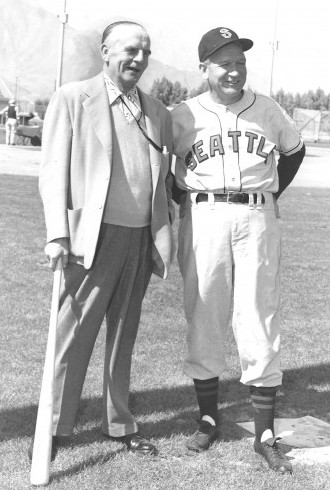

Two years after founding Century Brewing, which evolved into Rainier Brewing Co., Emil Sick had become one of Seattle’s wealthiest citizens, which conveniently for Torchy Torrance, coincided with Torchy’s determination to scratch his own persistent itch: Landing a job in professional baseball.

Torchy figured the way to do that was to find a new owner for the PCL’s Seattle Indians and convince the new bankroller that Torchy was just the man to run the franchise. So when Torchy began trolling for a man with money, he didn’t have to look very hard to locate Sick, a man he knew to be imbued with a profound civic conscience.

Under the ownership of William Klepper and John Savage, the Indians teetered on bankruptcy for several years. Unable to operate the club at a profit at Civic Stadium, designed as a football facility but pretty much a wreck of a ballpark for baseball, the Indians faced eviction from the facility near the end of the 1937 season because they couldn’t come up with the rent and were deeply in debt.

Torrance first approached Pacific Car and Foundry owners Paul and Bill Piggot about purchasing the Indians and installing Torrance in a management position, but they weren’t interested. Torrance then pursued Teamsters Union founder Dave Beck, who had the financial wherewithal, but neither the time nor the interest.

In his 1988 autobiography, Torchy, Torrance described what happened next: Emil Sick went to a brewers meeting in New York, where Jake Ruppert, one of the East Coast’s leading brewers who also owned the Yankees, suggested that it would be a good asset for Sicks beer business to buy the ball team in Seattle. Dave Beck also told him it would be a good idea.

What Torchy didn’t mention was that before Sicks meeting with Ruppert, an old friend, he pulled Ruppert aside and whispered in his ear, planting the suggestion that Sick would make a great baseball owner in the West.

“When he (Emil) returned home, he called a meeting and I was one of those he invited,” Torchy wrote in his memoirs. “He said he was ready to buy the Indians if he could get the club at a reasonable price. I was made executive vice president and we worked out an arrangement to buy the franchise for $75,000, plus an additional $25,000 to be split between Klepper and Savage.”

Sick deemed the price acceptable, but snafus developed, owing largely to the fact that Klepper hadn’t been entirely forthcoming about the grim state of the team’s finances.

After agreeing to buy the team, Sick (and Torrance) discovered the Indians owed money to a variety of vendors all over the country. The PCL would not permit Sick’s purchase to close until the debt had been cleared. By the time Sick made good on it, he had paid $131,000 for a pathetic franchise (only two winning seasons in the previous decade).

The Seattle Indians officially became Sick’s Dec. 17, 1937. If they hadn’t, the Indians, according to Torrance, would have folded or sold to an out-of-state buyer.

What Sick, Torrance and their underlings did with the investment is such an integral part of Northwest sporting lore that it has inspired more than one documentary, many magazine articles and one notable book, published last year (see Wayback Machine: Rainiers & Pitchers Of Beer).

The story of the franchise under Sicks ownership has been told and re-told, but few recapped it better than Watson, a one-time Franklin High catcher who became Seattle’s pre-eminent newspaper columnist after his own playing days ended.

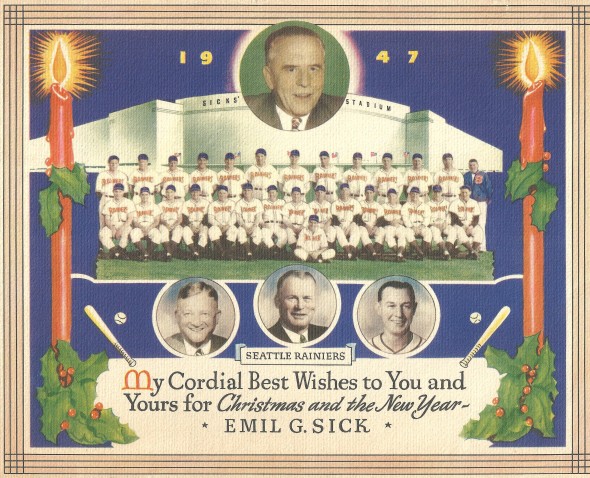

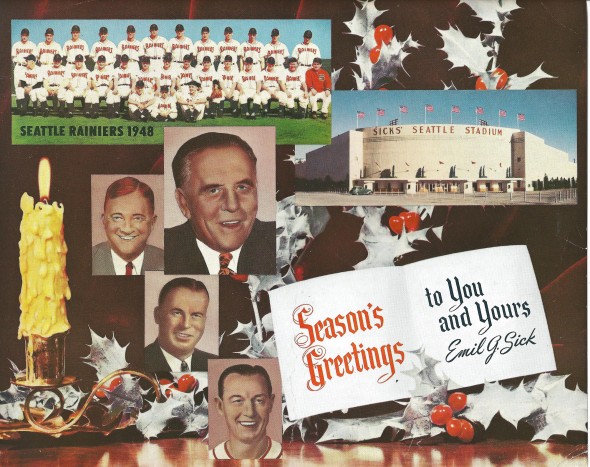

“Emil Sick, who owned Rainier Brewery on Airport Way South, bought the Seattle team when it finished a money-losing last in the Pacific Coast League,” wrote Watson. ”With his own cash he built Sicks’ Stadium, at Rainier Avenue and McClellan Street. He did not ask the taxpayers for a penny.

“He hired good men (Torchy Torrance and Bill Mulligan) and he stood aside, being heard only if they made a rash promise or a drastic mistake.

”Mr. Sick attended most games with his wife, Kit, a gracious woman who was a favorite among all of us. They were always thoughtful and kind to any of us who worked there. They made you feel you were really part of something good.

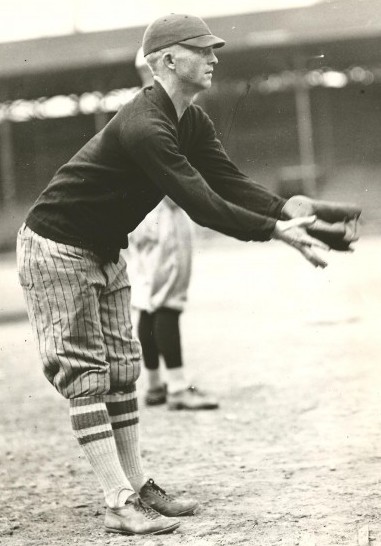

“He had good luck and he deserved it. He signed (with Torrance) Fred Hutchinson out of Franklin High School for a $5,000 bonus and a percentage of his major-league sale price. (see Wayback Machine: Hutch — A Man And An Award.)

“Hutch didn’t win just a few games; he won 25 (1938). Think of that! Eighteen and 19 years old, he won 25 games — and got Mr. Sick the nucleus of players that won three straight championships (1939-41).

“Out of Queen Anne High School he signed Edo Vanni. He gave Edo a $1,500 bonus and 4,000 shares of Rainier Brewery stock at 35 cents a share.

“The stock, which inevitably went up, helped Edo pay off his parents’ mortgage and build his own apartment house.

“Edo got the first hit, stole the first base and scored the first run in the brand new Sicks’ Stadium of 1938.

“In three successive years he hit .308, .321 and .330; the Rainiers won and the fans came in droves. Again, Mr. Sick was lucky.

“In 1939, he signed Dewey Soriano out of Franklin High. Dewey later became Mr. Sick’s general manager and put together the team that won the Rainiers’ last big pennant in 1955. Dewey was there among the old-timers.

“Unlike the buccaneer owners of today, Mr. Sick did deserve good luck, because he was kind, generous, straightforward and altogether a gentleman. In fact, Sick gave Seattle its brightest years of baseball.”

Watson’s statement about Sick giving Seattle its brightest years of baseball is still true, three and a half decades after Seattle became a major league city.

Sick believed it imperative to provide Seattle a first-class ballpark. He built Sicks’ Stadium at a cost of $350,000 in order to recoup his investment in the Indians. He changed their name to Rainiers solely to promote the Rainier brand of beer.

He was an unabashed capitalist, and the arrangement worked beautifully for all concerned: Seattle baseball fans enjoyed five PCL pennants during Sicks ownership, and fell in love with dozens of baseball heroes; Sick sold oceans of suds.

Ironically, before Sick purchased the Indians, he had never been much of a sports fan, and he never really got the hang of baseball in all his years as the team’s owner.

On rare occasions, he came into the clubhouse, Dick Gyselman, who played for the Indians and Rainiers from 1935-44, said after Sick’s funeral. He had a limited knowledge of the game and admitted it. But his enthusiasm overcame a lot.

“Emil never did understand baseball,” said Torrance, “and he’d take advice from the last place he got a haircut. As far as the Rainiers were concerned, Emil was not supposed to commit himself to anything until we had a chance to talk it over. But it didn’t always work out that way.”

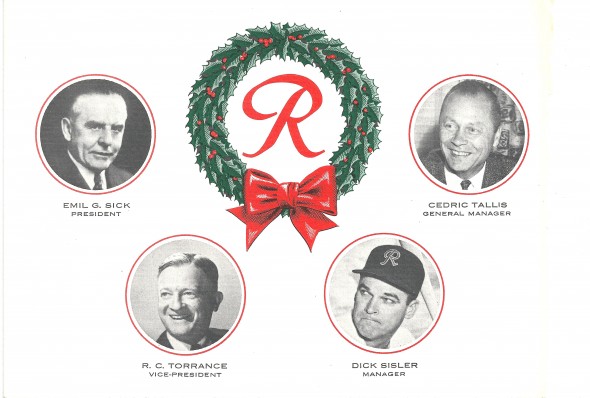

To illustrate his point, Torrance recalled in his memoirs an incident in late 1952, following the death of Earl Sheely, the Rainiers general manager. Torrance received a telephone call from Kit Sick, who advised Torrance that he should get hold of Sick right away. Emil, she said, was about to do something Torrance wouldn’t like very much.

”He (Sick) was in Los Angeles and I tried to reach him by telephone with no luck,” said Torrance. ”In the meantime, he had hired Leo Miller to be the Rainiers’ new general manager. Leo was a nice fellow and a close friend of Clarence (Pants) Rowland, the league president.

“But aside from that, he had no judgment as far as ball players were concerned and I knew he wouldn’t do a lick of work. Sure enough, he just sat around all year, drew his pay check and had a good time.”

Precisely because Sick became so successful, on his own merits as a brewmaster/businessman, and perhaps in spite of himself as a baseball owner, he placed himself in a much higher position than brewery operator and ball club owner. Sick had become a man who could get things done, meaning that he had no lack of people knocking on his door.

Since, according to Torrance, Sick had trouble saying no to anyone, he evolved into one of Seattle’s greatest civic treasures in areas far flung from beer and baseball (which was why, for example, Sick in 1949 became the first Washingtonian to win the Disabled Veteran’s Award for outstanding civic leadership).

In 1945, four years after the Rainiers had won the last of three consecutive PCL pennants (1939-41), Sick led a founders member committee that raised money to build the first King County Blood Bank, at the corner of Terry and Madison.

Sick’s efforts resulted in contributions of $100,000 for the construction of the building, plus an additional $145,000 to be used as a sustaining fund. Sick formed the founders committee and spent three years raising the cash.

Today, there are 20 blood banks in Western Washington and the former King County Blood Bank, subsequently re-christened the Puget Sound Blood Center, is famous for having pioneered breakthroughs in blood transfusion and transplantation medicine (check out the Lives Saved pages on the blood banks’ site).

That became the first Sick legacy that outlasted both his brewery business and baseball team. A year after the King County Blood Bank had been established, Sick was asked to serve as chairman of the Green Cross for Safety Campaign. The mission of this effort was to work for the prevention of all types of accidents, especially those on streets and highways, but also in homes.

In addition to pulling a stint as president of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, Sick became a trustee of the Seattle Foundation, an organization that encouraged (and still encourages) personal philanthropy to improve the quality of life in King County, and chairman of the Washington State March of Dimes.

Sick led annual fund-raising drives that netted the March of Dimes hundreds of thousands of dollars. In his capacity as chairman, Sick also raised funds on behalf of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis.

During Sick’s first decade as owner of the Rainiers, one of the prominent local news stories involved St. Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral, the magnificent “Holy Box” on 10th Avenue East on Capitol Hill.

A St. Louis bank financed construction of the cathedral beginning in 1928, but a combination of the 1929 stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression severely compromised the parish’s ability to make its mortgage payments.

By 1941, the Parish couldn’t make any, the bank foreclosed, padlocked the door and placed a “For Sale” sign on the front lawn that made national news.

St. Mark’s remained dark until 1943, when it was leased to the U.S. Army, which used it as an anti-aircraft training center during World War II.

Near the end of the war, Sick spearheaded a non-denominational effort aimed at getting St. Mark’s out of hock.

A committee formed by Sick, which included Teamsters boss Dave Beck, who had been an instrumental voice in Sick purchasing the Indians/Rainiers, first raised $100,000, allowing the Holy Box to re-open for worship in 1944. By 1947, the committee had raised an additional $250,000 to pay off all but $5,000 of the mortgage (the bank forgave the final $5,000), which was burned at the St. Mark’s altar on Palm Sunday, 1947.

The Museum of History & Industry (MOHAI) opened its doors Feb. 15, 1952. At a special ceremony held to mark the occasion, Sick served as one of the principal speakers, along with Gov. Arthur Langlie, Mayor William Devin and Mrs. Theodore Plestcheeff, president of the Seattle Historical Society.

Together, Sick, Langlie, Devin and Plestcheeff, made the formal presentation of the new MOHAI building to the city.

Sick had been asked to speak because led a $100,000 fundraising drive that made MOHAI possible. A year later, Sick was elected president of the Seattle Historical Society (Sick’s children later endowed a fund in the names of Emil and Kit Sick to promote publication of historical research by the University of Washington).

By 1957, the year that he began suffering from emphysema, Sick controlled the largest number of breweries under single management in the world, and had more titles than any man in town: Chairman of the Board of Sicks Rainier Brewing Co., president of Sicks Brewery Enterprises, Inc. (both of Seattle), director of Molson’s Brewery, Ltd., and Sick’s Breweries, Ltd. (both of Canada), and director of the Peoples National Bank of Washington. He would later add another title when he became one of the directors of the Seattle World’s Fair (1962).

Sick’s well-ordered, financially flush world began to change in 1958 when the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants relocated to Los Angeles and San Francisco, respectively. Until then, the Pacific Coast League had always enjoyed quasi-big league status, mostly because up until that time the westernmost outpost of the real major leagues was St. Louis.

The arrival of the Dodgers and Giants forced the PCL to relocate teams out of Los Angeles and San Francisco. Simultaneously, the PCL’s open classification collapsed and the league reverted back to AAA status. Almost overnight, the PCL’s dominance in the West evaporated, forcing many of the clubs to form working relationships with major league teams.

Numerous other factors contributed to the decline of the Rainiers, most notably the fact that Seattle had begun to view itself as a major league-ready city and not a minor league town anymore. Ill and exasperated and with no way to make the Rainiers profitable any more, Sick sold them in 1960 to the Boston Red Sox, who eventually sold them to the California Angels.

As journalist Dan Raley pointed out in “Pitchers of Beer,” Sick didn’t so much sell the Rainiers as he gave them to the Red Sox for $1, the price to make the transaction legal.

Sick, we imagine, would not have enjoyed the late 1970s much had he lived to see them. Over time, Rainier Brewery had launched a number of successful beer brands including Old Stock Ale, Club Extra Pale, Special Export Pale, Rheinlander and Sick’s Select.

As the 1970s progressed, each of these brands, as well as Northwest rival brands Lucky Lager and Olympia, began losing market share to major national brands and specialty microbreweries.

Rainier launched a memorable counter-attack in the late 1970s with a series of highly entertaining TV commercials — one featured a Lawrence Welk double (played by actor Pat Harrington Jr.) leading his band in “The Wunnerful Rainier Waltz,” complete with bubble machine and soloists blowing on beer bottles — but the tide against the brewery had become too large to stem.

In 1977, the brewery that Fritz and Emil Sick founded was sold to G. Heileman Brewing Co. It then passed through several more ownerships, including Pabst, which closed it in 1999.

Two years after Rainier left local hands (February 1979), Sick’s namesake ballpark (see Wayback Machine: The Fire That Changed Our Sports), over the objections of many, including Sick’s heirs, met the wrecking ball.

The stadium’s manual scoreboard, and some seats, went to Nat Bailey Stadium (built in 1951, using Sicks Stadium blueprints) in Vancouver, B.C., and its light standards to Washington State University. Several dozen box seats from Sicks Stadium were installed at Fairbanks Growden Memorial Park.

The iconic Rainier sign — the giant “R” that rotated atop the brewery for so many years — also found a home: in the collection of the Museum of History and Industry, which Emil Sick had helped make possible.

———————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports historian David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

19 Comments

My grandfather worked with the Rainiers for over two decades, and the word Grandma used to describe Mr. Sick was “grand.” He wasn’t someone who got close to his employees, but he took care of them and made sure things were done right and with style. I have Grandpa’s 1955 PCL pennant ring, and there’s nothing cheap about it.

A great piece about a “grand” man, an important figure in local sports history and arguably the best owner of a Seattle team in all sports over the years.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, than you for sharing your story.

My grandfather worked with the Rainiers for over two decades, and the word Grandma used to describe Mr. Sick was “grand.” He wasn’t someone who got close to his employees, but he took care of them and made sure things were done right and with style. I have Grandpa’s 1955 PCL pennant ring, and there’s nothing cheap about it.

A great piece about a “grand” man, an important figure in local sports history and arguably the best owner of a Seattle team in all sports over the years.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, than you for sharing your story.

Wonderful article. Emil Sick is an inspiration. Thanks for this.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, it was our pleasure. David sure has great images, doesn’t he?

Wonderful article. Emil Sick is an inspiration. Thanks for this.

On behalf of David Eskenazi, it was our pleasure. David sure has great images, doesn’t he?

Great read! Fondly recall visits to Sicks’ Stadium as a Little Leaguer in the late1950s and for Pilots games in ’69. Found no reference to Sicks’ involvement with the Pilots, but he must’ve had something to do with Seattle’s first major league team.

Sorry, Keith, but Mr. Sick had no involvement with the Pilots beyond bankrolling the ballpark they eventually played in. He passed away in November 1964, just two days before Fred Hutchinson died of cancer.

You are astute to note the fact that Sick died five years before the Pilots played in Seattle, and nine years after Sick sold the Rainiers to the Red Sox.

Hey Oly! Nice to hear from you!

Great read! Fondly recall visits to Sicks’ Stadium as a Little Leaguer in the late1950s and for Pilots games in ’69. Found no reference to Sicks’ involvement with the Pilots, but he must’ve had something to do with Seattle’s first major league team.

Sorry, Keith, but Mr. Sick had no involvement with the Pilots beyond bankrolling the ballpark they eventually played in. He passed away in November 1964, just two days before Fred Hutchinson died of cancer.

You are astute to note the fact that Sick died five years before the Pilots played in Seattle, and nine years after Sick sold the Rainiers to the Red Sox.

Hey Oly! Nice to hear from you!

Nice article about one of Seattle’s most interesting businessmen. Beer & baseball, is there any better combo!!

Nice article about one of Seattle’s most interesting businessmen. Beer & baseball, is there any better combo!!

My Dad and Uncle always spoke fondly of Mr. Sick as a great owner. They regularly received a station wagon load beer allocation from the brewery as a perk for playing in the organization! Great article, thanks for posting.