For six hours, from mid-morning to mid-afternoon Oct. 3, 1972, pedestrians passing the corner of Fifth and Pine in downtown Seattle witnessed a thickset, bushy-haired man wearing a ball cap and a large sandwich board attempt to engage everyone who passed near him. Printed on the board: ”Stop King Station Site. Petitions Here.”

Sign my petition! Sign my petition, the man pleaded. “Stop the lies!

Near the end of the one-man signature drive, a Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter approached the man in the ball cap and sandwich board and asked him what he was doing, and why.

“I am trying to get fans to say no to a domed stadium,” he replied.

Asked how he had fared collecting signatures, he said, “Been here six hours. I need 12,500 valid signatures. I already got 137.”

Asked by the reporter if he didn’t feel just a little bit embarrassed standing on a street corner wearing a sandwich board begging for signatures, the sandwich board man said, ”My wife asked me that and the answer is, heck no. I’m enough of a ham to enjoy it.”

Finally, one passerby yelled, “Jeff Heath! Jeff Heath, of all people! Jeff Heath biting the hand that fed you. After all that baseball did for you!”

Heath told the P-I reporter that he wanted a new ballpark as much as the next guy. But he did not believe that a domed stadium near the King Street Station could be built for $40 million, the price tag King County politicians were dangling in front of voters who had been asked to fund the facility.

“Philadelphia just got a new stadium (Veterans) for $42.7 million,” Heath explained. Cincinnati’s got a new one (Riverfront) for just under $50 million, and Pittsburgh’s new one (Three Rivers) cost just over $40 million. All three of those are open stadiums, and a dome, especially where they want to build it here, would cost a lot more.

”If they’d (King County politicians) just level with us and say, ’Okay, were going to need another $30 million to do the job right,’ I could buy that. But if they persist in trying to do it for $40 million, it’s going to be a shoddy job. Theyll have to leave out something. Besides, our weather isn’t bad enough to require a dome. We aren’t a bunch of sissies.”

Had Heath been in charge of ballpark planning, he said he would have reconfigured Husky Stadium instead of pursing what he deemed the folly of a domed stadium.

“I’ve always felt a permanent big-league stadium, for baseball and football, should be at the University of Washington, Heath said. “I looked the stadium over carefully. By cutting a pie-shaped piece out of the student section, 21 rows back of the moat, you could accommodate baseball.

“Add some double decking on the north side (ultimately done) and you’d have a great ball park. Double deck the whole thing and you’d have 100,000 seats. And youve already got the parking.”

Jeff Heath ultimately failed in his attempt to squash construction of what became the Kingdome, but lived long enough to see his cost projections validated. The Kingdome’s final price tag came in at $67 million, $27 million more than what King County officials said it would (imploded in 2000, 25 years after Heath’s death, the Kingdome’s debt won’t be retired until 2015).

One thing about Heath, in or out of a sandwich board: He never shied away from speaking his mind. Or controversy. Or using his fists. Sports writers of Heath’s day frequently used the word ”madcap” to describe him. They also used “funny,” “crass,” “moody” and “complicated.” One Cleveland columnist called Heath “the most misunderstood man in baseball.”

Baseball scribes who chronicled Heath’s career, particularly those in Cleveland, where Heath made his debut as a major leaguer, insisted he could have become stupendous (the numbers bear this out), perhaps one as great as Snohomish Hall of Famer Earl Averill (see Wayback Machine: The Earl & Pearl Of Snohomish), but that he merely became a very good one because he lacked the discipline to achieve greatness.

Born April 1, 1915, in Fort William, Ontario, Heath moved with his family to Victoria, B.C., when he was a year old. Seven months later, Jeff’s father relocated the family to Seattle, where he ran a hardware store.

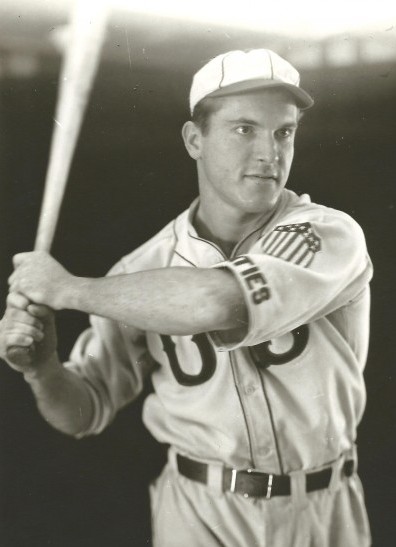

Heath attended Garfield High and made the varsity baseball team as a 14-year-old freshman. He had a natural aptitude for the sport, but could also have been an outstanding football player. All-City in 1933-34 as a fullback, Heath received dozens of scholarship offers from schools such as Washington, Oregon, California, Alabama and even Fordham.

Heath ultimately chose baseball after suffering several injuries to his ankles and knees playing football for Garfield, from which he graduated in 1934.

A year later, Heath signed with the Yakima Indians of the semipro Northwest League, and immediately showed he made the correct choice of sports. After batting .390 in 75 games, Heath received an invitation to join a U.S. amateur All-Star squad that was scheduled to tour Japan.

After Heath batted .483 on the trip, William Kamm, a scout for the Cleveland Indians, signed him to a contract for a reported $5,000. Cleveland assigned Heath to one of its affiliates, the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association.

From there, Heath moved to the Zanesville, OH., Greys of the Class C Mid-Atlantic League and put up such ridiculous numbers in 124 games — .383 batting average, 208 hits, 47 doubles, 14 triples, 28 home runs – that he earned a late-season promotion to the parent Cleveland Indians.

If not for Walter Alston’s 35 home runs for the Huntington Red Birds (Alston would manage the Dodgers for 23 years, from 1954-76), Heath would have won the Mid-Atlantic League’s Triple Crown. As it was, Heath made a nearly unprecedented leap from Class C ball to the major leagues.

The Indians first started Heath in left field Sept. 13, 1936, only two years after hed graduated from Garfield, against the Philadelphia Athletics. Next door in center stood Snohomish native Averill, en route to a 232-hit, .378 BA season. Heath’s opposite in left, Bob Johnson of Connie Mack’s Athletics, hailed from Tacoma.

Heath went 1-for-3 with a walk to Averill’s 1-for-2 (two-run double), and over the next 12 games hit .341 in 41 at bats, half of his 14 hits for extra bases.

Despite that showing, the Indians determined Heath would be better served spending more time in the minors, and assigned him to the franchise’s top farm club, the Milwaukee Brewers, for the 1937 season. The demotion lasted 100 games, during which Heath hit .367, 57 of his 164 hits for extra bases.

Cleveland deemed the 23-year-old Heath major league ready in 1938, and why he did not make the American League All-Star team that year can only be attributed to the glut of great AL outfielders, including Averill and Joe DiMaggio.

Heath delivered 172 hits in 126 games (that’s Ichiro in his prime) and batted .343 with a league-leading 18 triples, 21 home runs and 112 RBIs. His .343 average trailed batting champ Jimmie Foxx by just six points, and his .602 slugging percentage ranked third to furture Hall of Famers Foxx (.704) and Hank Greenberg (.683).

Heath out-performed Foxx, Greenberg and every other American Leaguer in August that year, producing 58 hits, a staggering monthly total no major league player would approach until Ichiro had a career-high 56 in August of 2004.

On two occasions in 1938, Heath and Averill made significant contributions to Cleveland victories. On Aug. 12, both had four hits in a 12-9 win over the Chicago White Sox. Two weeks later, Aug. 27, Heath, batting cleanup, went 3-for-6 with three RBIs and Averill, hitting behind him, 4-for-4 with two RBIs.

By the end of 1938, Cleveland sports writers began referring to Heath as ”The Natural,” and gushed rosy predictions about his future, at least two suggesting a Hall of Fame career might be in the works. But Heath mysteriously struggled at the plate over the next two seasons, even hitting as low as .219 in 100 games in 1940. Cleveland’s scribes stopped calling him ”The Natural” and started to write that Heath was a troublemaker.

But Heath roared back with a 1941 campaign much like the one he’d had in 1938. He topped the AL with 20 triples, batted .340 (fourth in the league), and finished third in slugging behind Ted Williams and DiMaggio. Heath also finished second in total bases and RBIs (behind DiMaggio) as well as second in hits (199), made his first All-Star team, and finished eighth in Most Valuable Player voting.

But the very next year (1942), Heath’s batting average plunged to .278 and he knocked in only 76 runs. Heath hit .274 with 18 home runs in 1943 and made the AL All-Star team, but performed nothing like the player he had been in 1938 and 1941. In fact, he never came close to 1938 or 1941 again.

Several aspects of Heath’s 14-year career pop out. On July, 25, 1939, pinch-hitting for future Rainiers manager Luke Sewell (1956), Heath tied a major-league record with two pinch hits in one inning, a double and a triple. When Bob Feller threw his Opening Day no-hitter in 1940, Heath scored the game’s only run.

In 1941, Heath became the first player in AL history to hit 20 or more doubles (32), triples (20) and home runs (24) in one season. Thirty-eight years would elapse before George Brett, in 1979, duplicated the feat in the AL, and another 28 before anyone else (Curtis Granderson, 2007) did it again.

From 1945 to 1955, Heath held the major league record for career home runs by a player born outside the United States.

In 14 seasons, Heath batted .300 five times, producing 18 four-hit games and 96 three-hit games. He had seven RBIs in an 11-4 win over the Athletics Aug. 27, 1941, five RBIs six other times, and scored five times Aug. 20, 1938.

On Sept. 4, 1947, playing for a St. Louis Browns team that included three future Seattle Rainiers, Wally Judnich (1950-53), Al Zarilla (1954) and Vern Stephens (1955-56), Heath hit a game-winning, two-run homer off Franklin High alum Fred Hutchinson of the Detroit Tigers.

While Heath accomplished much, finishing with a lifetime average of .293, it’s clear he could have done much more (Heath even admitted it). But Heath sabotaged himself through a combination of immaturity, hot-headedness and, if his critics can be believed, dwelling on the negative. For much of his career, Heath was an unhappy ballplayer.

That stemmed first from Heath’s conviction that the Indians never paid him what he felt he was worth ($40,000 as a top salary). He became a contract holdout after his first full season and held out many times after that, a stance that annoyed many of his teammates and specifically irked his manager, Oscar Vitt, who ran the Indians from 1938-40.

Heath also had trouble controlling what evolved into a legendary temper. On Aug. 27, 1939, after whiffing against Denny Galenhouse of the Red Sox (Heath and Galenhouse became teammates on the 1950 Seattle Rainiers), Heath threw his bat in frustration. It landed in one of the box seats, glancing off Cleveland Press editor Lou Seltzer. Bill McGowan, the home plate umpire, tossed Heath.

When Heath returned to the dugout, steaming, he got into a fist fight with teammate Johnny Broaca. The next day, Aug. 28, after Heath fouled out on a 3-0 pitch he should have taken, a fan yelled, Why don’t you throw your bat in the stands again?” Heath charged the man and punched him in the chest.

Heath feuded with Cleveland sports writer Ed McAuley, threatening to punch him out after McAuley wrote that Heath was not a good team man and did not always give 100 percent. Another time, Heath, according to Feller, his roommate, took out a cameraman who offended him with one punch.

Heath spent most of one season, 1940, leading a player revolt against Vitt. When the Cleveland press identified Heath as the ringleader, his batting average plummeted. The press labeled the team the Cleveland Cry Babies, but the Indians got rid of Witt.

After Heath’s numbers sagged again after his great 1941, Heath blamed Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium for his slide, insisting he would hit more home runs if the stadium wasn’t 470 feet to dead center and 435 in the power alleys.

Lou Boudreau, who replaced Roger Peckinpaugh as Cleveland’s manager in 1942, blamed Heath for Heath’s erratic performances, telling Baseball Digest in 1943 that Heath did not always deliver maximum effort, or work hard enough, and that when he got frustrated he gave up (in one game, according to Boudreau, Heath let a ball drop in front of him without making any effort to catch it).

Feller blamed Heath’s failure to make the most of himself on Feller’s belief that Heath didn’t take baseball – or life – seriously enough. Indians pitcher Harry Eisenstat told The Cleveland Plain Dealer, ”If he’d go 0-for-4, hed complain that the pitcher wasn’t very good. He’d keep talking about it. He dwelled on the negative.”

By 1945, the Indians had grown weary of Heath and traded him to the Washington Senators for outfielder George Case. Heath didn’t like cavernous Griffith Stadium, either, so the Senators sent him to the St. Louis Browns at the mid-point of the 1946 season.

The reason, according to SABR (Society of American Baseball Research): “Sherry Robertson’s relationship to Senator owner Clark Griffith caused Heath to ride Robertson on the bench during games unmercifully about being a lousy player but the ‘owner’s pet.’ Heath wanted a fight. This led to the mid-season trade to the Browns.”

Heath wore out his welcome in St. Louis inside of two years, the final straw coming in the final game of the 1947 season.

The Browns and White Sox found themselves tied 5-5 heading into the bottom of the ninth. The Browns loaded the bases with one out when Heath’s turn to hit arrived. But Heath had gone MIA. When a batboy located him, he was taking a shower. Although he had just hit a career-high 27 home runs was only 31 years old, the Browns sold him to the Boston Braves for $20,000.

Heath provided another glimpse of what could have been after he joined the Braves in 1948. Hitting .319 with 20 home runs in 115 games, he became one of the primary reasons Boston won the pennant. Heath couldn’t wait for the World Series, his first, especially since the Braves would play his first club, the Indians. But Heath never got there.

On Sept. 29, Heath fractured his lower left tibia and severely dislocated his left ankle sliding into home plate in the sixth inning against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field. Heath had hit a long double and was trying to score on a single to right by Bill Salkeld (father of future Mariner No. 1 draft pick Roger Salkeld). Gene Hermanskey’s peg to the plate was true and in time and Heath, seeing the ball skip into Roy Campanella’s mitt, flung himself to the left in a hook slide. His spikes caught in the hard-baked ground and he wound up on his back with his legs crossed.

Although Heath returned to Boston in 1949 for 49 games, the play at the plate the previous September effectively ended his major league career. His final hurrah in the majors occurred in mid-August, when he bombed eight home runs in 18 games, including a pair off future Rainier Ewell Blackwell (played on Seattle’s 1955 PCL champions) Aug. 27, the last one a 10th-inning walk-off.

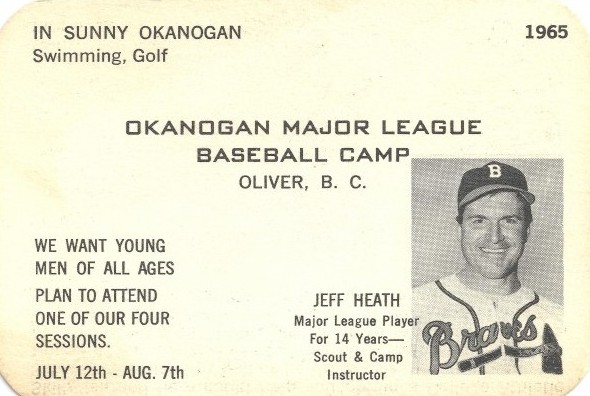

Although the Braves released Heath after the 1949 season, they had difficulty believing he’d been a problem for other clubs. As SABR noted, ”He certainly ended his career on a high note with the Braves. Some late-arriving maturity undoubtedly helped. He had even signed his Braves contracts promptly and without quarrel.

“(Manager) Billy Southworth said, ‘They told me when I got him from the American League that Heath was a troublemaker. If he was, Id like to have eight other troublemakers like him.'”

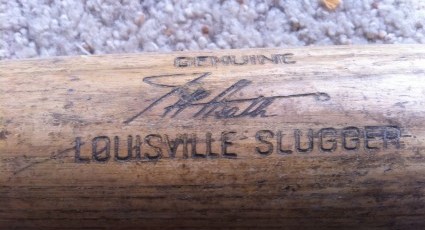

The following spring, Heath, back in Seattle, asked Rainiers GM Earl Sheely for a tryout. Heath launched several home runs at Sicks’ Stadium, after which a Seattle reporter disclosed that Heath had paid the batting-practice pitcher $100 to groove the pitches. Both Heath and Sheely denied the story, and Heath signed with the club.

With his mobility gone, Heath managed to get in only 57 games (hit .245) before receiving his release, by mutual consent with Rainiers management, July 2, 1950.

“The goods are damaged,” Heath told Lenny Anderson of The Times. ”I don’t care what you’re getting or who you are. You hate smelling out the joint. But after 15 or 16 years of baseball, its sort of hard to quit.”

”John Geoffrey Heath looked indestructible,” columnist Georg N. Myers wrote in The Times. “He was an oak of a bloke, thickset, with massive shoulders and a neck of outsized circumference. But spirit sustains flesh only so long.”

For the first time since his graduation from Garfield, Heath separated himself from baseball. He moved to Bow, WA., in rural Skagit County, and tried his hand at dairy farming. That didn’t suit him. For a while, he sold real estate in Kitsap County. Heath didn’t take to that, either, and returned to Seattle, still looking for a gig that fit.

A couple of years after Heath’s career ended, Franklin Lewis of the Cleveland Press asked Heath what he would do differently if he had his career to do over. Heath said, “I wouldn’t gag around as much. I shouldn’t have popped off. It’s all right for little guys to talk loud, but not a big ox like me.”

At about the same time, Baseball Digest published an article, under Heath’s byline with the following headline: “I Did It The Wrong Way!” In the piece, Heath admitted to youthful impulsiveness and being headstrong.

But, as Myers wrote in The Times, ”Heath was likeable and could enliven any crowd.”

Myers told this story:

“There was a night (winter, 1957), when Dewey Soriano, then general manager of the Seattle Rainiers, was introducing Lefty O’Doul, his next field manager, at a Hot Stove League gathering.

”Dewey at his most eloquent outlined Lefty’s well-known baseball background, propounded his virtues, and dwelled on his gift of leadership. Suddenly, from the back row, came the loud question, asked amid a chortle.

”Hey Dewey, isn’t that what you said about Luke Sewell (who had flopped as the Rainiers’ manager in 1956) last year?”

Even Dewey Soriano laughed.

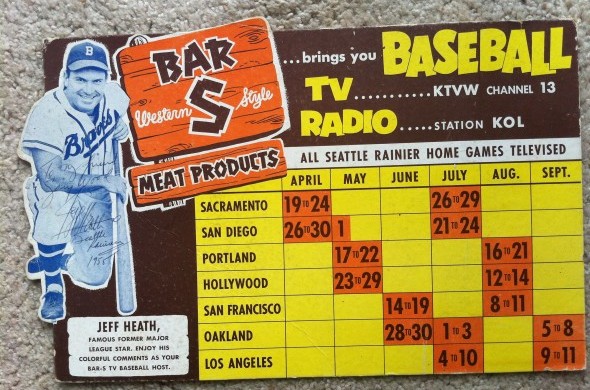

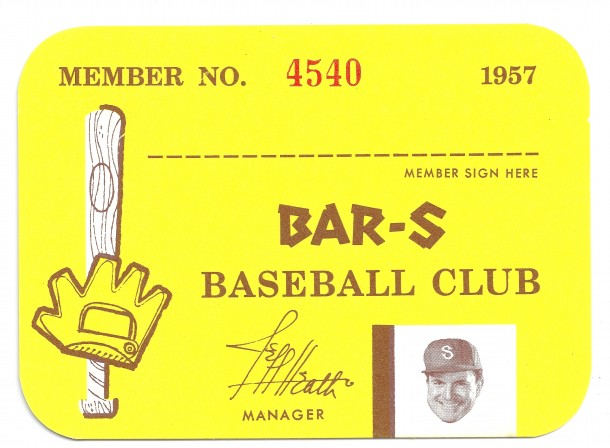

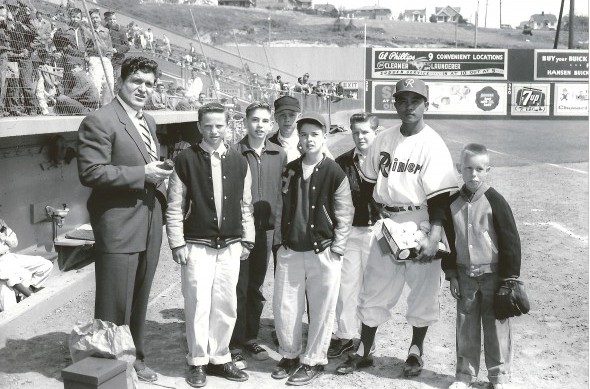

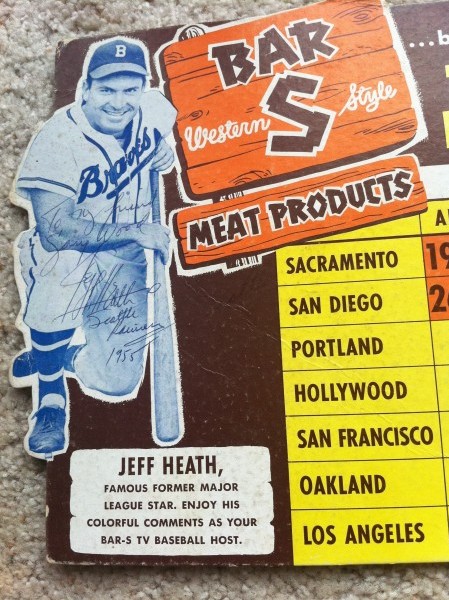

Because of Heath’s gregariousness, if not his well-fed look, hot dog manufacturer Bar-S Meats selected him to do the color on Rainiers telecasts on KTVW-TV (Channel 13) after KTVW out-bid KING-TV for the rights. This is how author Dan Raley described Heath in his book, Pitchers of Beer:

“A man with rugged looks and a thick build, Heath also had a little Dizzy Dean in him, offering various homespun observations to the listeners. Endearing himself to everyone, he usually took batting practice with the Rainiers players before each game. Standing around home plate, Heath was crass and entertaining, often doing a dead-on Babe Ruth impersonation. He would feign staggering up to the plate as if hung over, mention something about his lack of sexual prowess the night before, and tap the plate.

“He had his pants pulled up, shirt out indicating a bulging waistline, all classic Ruth characteristics. Bar-S Meats, the TV broadcast sponsor, couldn’t have been more thrilled to have this guy in the booth because he had a Bambino-like appetite. In his typically unpolished manner, Heath would wolf down free Bar-S hotdogs and then, between belches, tell the audience how great this particular ballpark concession offering was.”

“He was a remarkable person in many respects and a pathetic person in many respects,” Bill Sears, a long-time Seattle publicity man (see Wayback Machine: Bill Sears And A Life Well Lived), told Raley. “Heath was really crude on TV but that was part of the appeal. He’d butcher words and you never knew what he was going to say next.”

To Bar-S’s delight, Heath earned the sobriquet ”Mr. Seattle Hot Dog” from The Times’ Anderson, who had previously dubbed Heath “Mr. Butterfat” during his stint as a dairy farmer.

To Bar-S’s chagrin, Heath occasionally made inappropriate remarks into the microphone, forcing him to apologize, and he took an intense dislike to the TV show’s producer, Bill Veneman. One night, Heath chased Veneman around the studio, threatening to throw him out the window. Veneman threatened to fire Heath, but couldn’t because Bar-S wouldnt hear of it. Heath had become too popular.

Bar-S exploited that popularity in another way. Many newspaper advertisements touting its various products included a short column by Heath titled ”Hot From HEATH.” In it, Heath commented for two or three amusing paragraphs on the latest Rainiers doings, and he always ended his lively spiel with a postscript.

The one that ran March 26, 1956, in Seattle newspapers, nominally about Rainiers pitching prospects, ended with, ”P.S.: Ordered bacon and eggs for breakfast this morning. The eggs were okay, but the bacon was so shriveled it looked like it was trying to hide. Sure look forward to a man-sized serving of Bar-S thick-sliced bacon.”

Bar-S ran another ad June 13, 1956 tempting readers with its “Boneless Cooked Holiday Hams.” The copy read: “Fully cooked, delicious Bar-S Boneless hams – the ones Jeff Heath talks about on baseball! Average 6 to 10 lbs, and you have a choice of whole or full half!” Bar-S labeled many of its products, especially bacon and wieners, “Jeff Heath Specials.”

Heath became an in-demand public speaker. In March, 1956, for example, he orated in front of the Roosevelt Lions Club, Knights of Columbus and Seattle chapter of the Theta Chi Alumni Association. He also made guest appearances at local Tradewell stores and interviewed guests on John Jarstad’s Hot Stove League program on Channel 13. In 1957, Seafair name Heath its “Prince of Mirth” and placed him in charge of Seafair clowns.

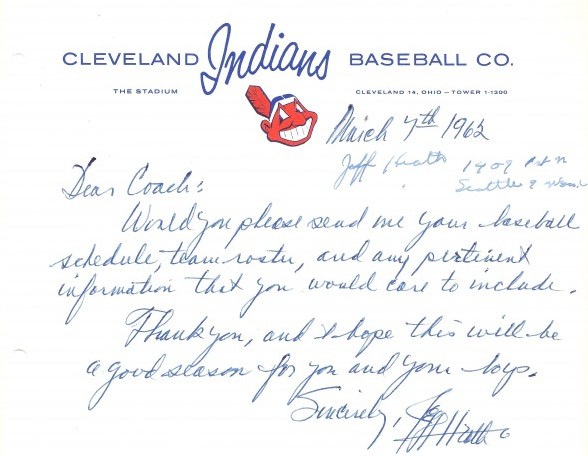

Three years later, in 1960, Heath suffered a heart attack at the age of 43. But he recovered and continued to broadcast baseball and revel in his local celebrity. In 1968, Heath joined the Seattle Pilots as a scout and member of their speakers bureau. After their single season in Seattle (1969), Heath, with no other baseball-related job available, became involved in real estate development.

On Dec. 9, 1975, three years after he’d donned a sandwich board and lobbied against the construction of the Kingdome, many of Heath’s friends, former teammates and associates were attending a memorial service for longtime Indians/Rainiers broadcast legend Leo Lassen when they learned that Heath had died at his Queen Anne home of a heart attack.

In an obituary by Howard Preston in the Cleveland News, Preston wrote, “He was a mixture of gentleness and brute strength, angel and devil, but withal an exciting fellow for what he might have been as well as for what he was.

What he was, according to Myers of The Times, was this: A complete stranger to inhibition.

———————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Another great story…Earl Averill looks as crabby in 1969 as he was in 1974 when I met him at an old-timers day before a Seattle Rainiers game at Sicks.

Jeff Heath has for some time impressed as a guy who had a lot of talent on the field (that he occasionally used) but wasn’t always the easiest person to get along with…not what I’d consider an ideal teammate. This piece pretty much underlines that, although it sounds like he was starting to “get” it long after he retired.

Another great story…Earl Averill looks as crabby in 1969 as he was in 1974 when I met him at an old-timers day before a Seattle Rainiers game at Sicks.

Jeff Heath has for some time impressed as a guy who had a lot of talent on the field (that he occasionally used) but wasn’t always the easiest person to get along with…not what I’d consider an ideal teammate. This piece pretty much underlines that, although it sounds like he was starting to “get” it long after he retired.