By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Had it not been for the extreme cold that gripped Seattle, the charity football game at Memorial Stadium Dec. 6, 1953 likely would have attracted a far larger crowd than it did. But with temps in the mid-20s and icy rain in the forecast, its remarkable that 5,200 braved the elements. That they did spoke mainly to the drawing power of Don Heinrich.

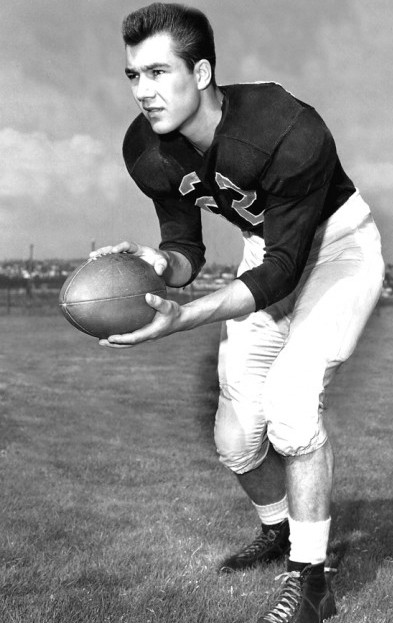

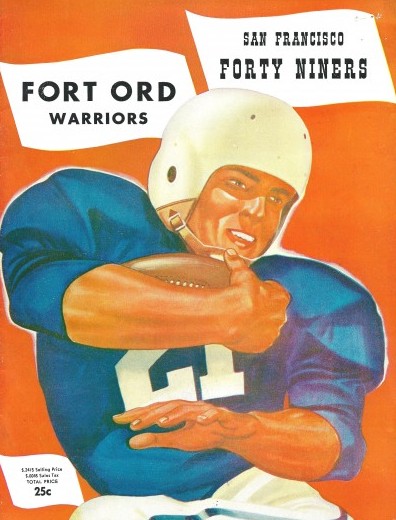

A year removed from the University of Washington, where he had been a two-time All-America, Heinrich quarterbacked the Fort Ord (CA.) Warriors, the nations top-ranked service team that came to town to play the semipro Seattle Ramblers in a benefit for the blind sponsored by the Queen Anne-Magnolia Lions Club.

Billed as The Queen City Bowl, and written about in the newspapers for days, the game had been held annually for four years and become one of Seattle’s newer sports traditions. It attracted some of the best players in the country to the city.

Fort Ord featured a dozen players who had spent time in the National Football League as well as several college All-America picks, including Heinrich, who were waiting to sign with NFL clubs once their military commitments were fulfilled.

Among Fort Ords pros, running back Ollie Matson stood above the rest. He had been a 1952 All-Pro as a rookie with the Chicago Cardinals and a member of the 1952 U.S. track and field team at the Helsinki Olympic Games.

Fort Ord brought a 9-2 record into the game, having defeated its opponents 335 points to 37 with Matson scoring 15 touchdowns. Fort Ords only losses had come to the Los Angeles Rams and San Francisco 49ers in exhibition contests.

The Seattle Ramblers, coached by Don Sprinkle, included several former University of Washington players, notably Bob Levenhagen, Jim Warsinske and Tom Sprague, all of whom had been teammates of Heinrich before his induction into the Army in 1952. But the Ramblers were no match for Heinrich’s Fort Ord club, losing 28-0.

Like an Army division rotating its regiments in battle, Fort Ord shuffled three complete teams on and off the field in an outstanding display of football mastery, wrote The Seattle Times.

Matson lived up to all expectations, netting 122 yards on nine carries for a 13.6-yard average and two touchdowns. Dave Mann (ex-Oregon State) averaged 52.5 yards on six kickoffs, scored a touchdown on the most spectacular play of the game, and kicked all four extra points.

Heinrich didnt have to do much more than hand the ball off, but worked in a 43-yard touchdown pass to Pete OGara, a former UCLA end, to climax an 82-yard Fort Ord drive.

Heinrich played the entire game in large part because a majority of fans had come to see the former Husky All-America, whose presence helped generate $54,000 in proceeds for the Queen Anne-Magnolia Lions.

Heinrichs Dec. 6, 1953 appearance at Memorial Stadium turned out to be his last in the facility. His first occurred Thanksgiving Day, 1947, when, in the stadiums dedication game, he directed Bremerton High to a 19-14 victory over the Ballard Beavers in the Seattle vs. The State game to climax an undefeated season

The son of Navy foundryman Conrad Heinrich, Don Heinrich, born in Chicago Sept. 19, 1930, announced himself an emerging Northwest football legend in that contest, completing eight of 11 passes, two for touchdowns. In addition, Heinrich stopped a Ballard scoring threat when Ernie Humphries, the Beavers quarterback, took a second-quarter kickoff and raced 72 yards before Heinrich caught him from behind.

Also an All-Stater in basketball, Heinrich became the subject of much public fawning following that game. Every school on the West Coast, and even one in the South, sought him, promising him free Rose Bowl tickets and $250 per-month jobs if he would commit, big lures in those days.

Heinrich did not commit until the summer after his senior year, and when he did he selected the University of Oregon. At that time, Washington seemed too downtrodden to have a chance at a player of Heinrichs skill.

But big things were afoot at UW. In February, 1946, Washington regents appointed Harvey Cassill athletic director. A former business executive, Cassill came to campus with a grandiose vision for Husky athletics: He wanted to make Washington a national athletic power, the West Coast equivalent Notre Dame.

Cassill did a lot in a short amount of time. He signed the first home-and-away football games with Notre Dame; secured the rights to both the 1949 and 1952 Final Fours and 1951 NCAA Outdoor Track & Field Championships.

I hope to develop policies that will enable us to produce teams that rank with the best in the country, Cassill said when he was hired.

But, I am completely opposed to any wholesale importation of talent or buying of teams. We might do so and get away with it, but it just isnt worth it.

This university is going to go first class in intercollegiate athletics, or not at all. But we want students from our state on our teams, seconded UW president Dr. Raymond Allen.

By the time Cassill came aboard, the UWs alumni association had gone dormant, and many of the states best high school players were opting for Washington State or going out of state.

An enthusiastic UW grad (1924), Cassill got together with alumni director Curly Harris and mapped out a strategy to organize alumni clubs around the state, then instructed Chuck Bechtol, an All-Coast quarterback in 1938-39 who had become one of Cassills assistants, to implement it.

Bechtol, who would later become an executive with PACCAR Inc., ultimately organized 22 clubs, one in Bremerton, home of Oregon-bound Don Heinrich. Bechtol, in fact, organized the Bremerton club specifically with Heinrich in mind.

Cassill, meanwhile, had a chance to hire both Bernie Bierman and Clark Shaughnessy, two well-established head coaches with national reputations, as a replacement for Ralph Pest Welch, but elected instead to hire the less-experienced but much younger Howie Odell, figuring a younger coach would better relate to players.

Odell, who had come from Yale, and a group of Bremerton-based Husky alums met with Heinrich and, over the course of a week, talked him out of enrolling at Oregon, one of the greatest recruiting coups in Husky history.

After playing for the UW freshmen in 1948, Heinrich joined the varsity in 1949 and threw for 899 yards in 10 games, including seven starts. His total broke Anse McCulloughs school record of 618, set in 1948.

The first home game of 1950 became a highlight event in UW history as Heinrich and Hugh McElhenny saw their first varsity action in a Husky Stadium that featured a new, south-side upper deck. After the Huskies introduced their 50th anniversary all-time team to mark the occasion, Heinrich and McElhenny took their first steps toward becoming Husky legends (see Wayback Machines McElhenny’s 100-Yard Punt Return and Hugh McElhenny & The Kings).

McElhenny darted 91 yards for a TD, the longest scrimmage run in school history (old record 85 yards by Ervin Dailey against Whitman in 1919), and then Heinrich threw the longest touchdown pass in school history, 65 yards to Roland Kirkby, breaking the previous mark of 63 by Freddy Provo to Dev Gossett against Stanford in 1946.

Washington rolled over Kansas State 33-7 as Heinrich threw two more TDs to Kirkby and another to Fritz Apking, his quartet of scoring passes breaking his own school record of three set the previous year against UCLA.

Washington had two other memorable games in 1950, the first Nov. 4 against California, which featured one of the most groan-inducing plays in Husky history, a fumble that cost UW a chance to play in the Rose Bowl. UW had the ball on the Cal two-yard line trailing 14-7.

In the huddle, Heinrich called for a play that was a wide pitchout to McElhenny, said former Heinrich teammate Jim Wiley. The team ran out of the huddle and Heinrich saw that Les Richter knew right where the ball was going. So Don called for the automatic pass.

“All the end was supposed to do was step into the end zone and take a jump pass for a touchdown. Heinrich made his jump, but while he was in the air he saw the end jammed up. Don still had the ball when he came down and was hit immediately. The ball went flying, and there went the Rose Bowl.

Later, when Washington met Washington State, Heinrich got a better result. With the Huskies leading 45-14, Heinrich went to the bench, believing he had established a national single-season pass completions record of 133. But with time running out, UW discovered Heinrich only tied the record. One of the Washington players suggested to Odell that he allow Washington State to score so that Washington could get the ball back and give Heinrich a chance to break the record.

Which is exactly what happened. The Huskies gave the Cougars an uncontested touchdown, Heinrich re-entered the game and completed a short pass to set the record. Moments later, McElhenny busted loose for an 84-yard touchdown, giving him 296 yards and a UW a 55-21 victory.

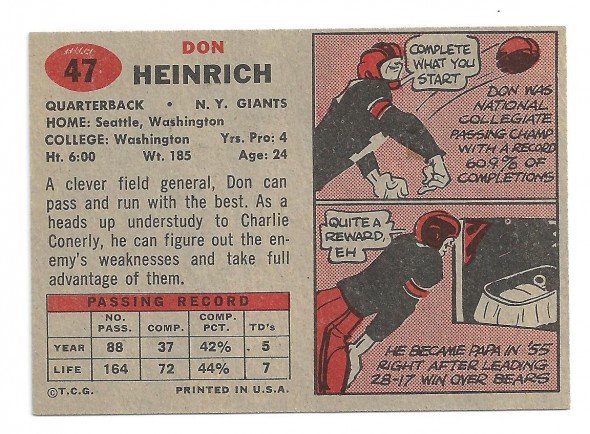

Heinrich was named Washingtons 11th All American Dec. 5, 1950 after every school on the Huskies schedule voted him to its all-opponent team. Heinrich had completed 60.9 percent of his passes, a figure exceeded only once in the Pac-8/10 during the next 26 years.

As Seattle sports writers began writing about the 1951 season, they introduced numerous nicknames for Heinrich, most famously The Arm, Deadeye Don and The Bremerton Bazooka.

But a separated shoulder, suffered in practice a week before the opener against Montana, shelved Heinrich for the entire season, depriving UW fans of watching Heinrich and McElhenny in what would have been their final season together.

With McElhenny having gone to the 49ers in the 1951 draft, Odell emphasized a passing attack in 1952 and Heinrich responded with 137 completions to better the national record of 134 he set in 1959. Among Pacific Coast Conference passers, Heinrichs 137 completions were 77 more than the 60 by Bob Garrett of Stanford and 82 more than the 55 by Oregons George Shaw.

Heinrich, who joined TCUs Davey OBrien as the only players to lead the nation in passing two years in a row, again made first-team All-America, become the first two-timer in school history.

Although he also coached McElhenny, who would make the College Football Hall of Fame and Pro Football Hall of Fame, Odell always thought Heinrich was the greatest player he coached, and said so in an article he wrote for the Oct. 7, 1952 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Don was something special in the huddle, said Wiley. He had the knack of making everybody feel he was important. After a half-dozen or so plays in a game, he would start asking offensive linemen questions: OK, what have you got to tell me? Who have you found thats soft? His big asset is that kind of secret sense of looking at a defense and knowing what to run against it.

The Army inducted Heinrich Nov. 25, 1952 and he actually needed a pass to play against the Cougars four days later (Nov. 29). That game ended Heinrichs UW career he set all the schools passing records and would hold most until Sonny Sixkiller came along two decades later — and marked the last any Husky fan saw of him until he arrived at Memorial Stadium with the Fort Ord Warriors more than a year later to face the overmatched Ramblers.

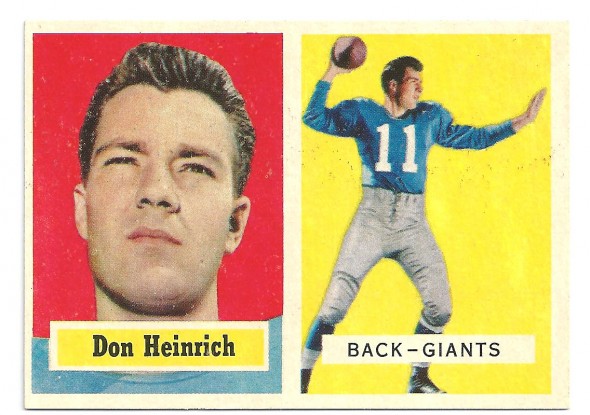

Following Fort Ords easy win, Heinrich and Matson led the Warriors to a 44-19 victory over the Quantico Marines (featuring future Iowa coach Hayden Fry) in the Poinsetta Bowl for the national service championship, and a 67-12 win over the Great Lakes Navy in the Salad Bowl in Phoenix. Heinrich then joined the New York Giants, who made him their No. 3 pick in the 1953 draft.

Heinrich worked as the Giants starting quarterback in 1955-56 and split time at the position with Charley Conerly from 1957-59. His 56-game NFL career included a cameo in the 1958 NFL Championship, The Greatest Game Ever Played.

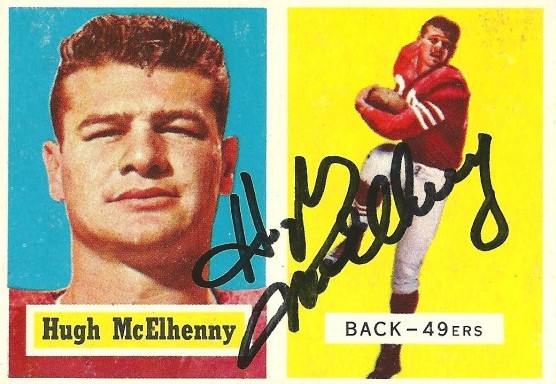

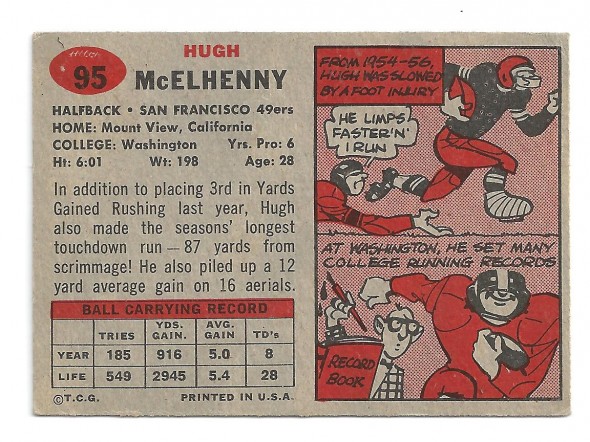

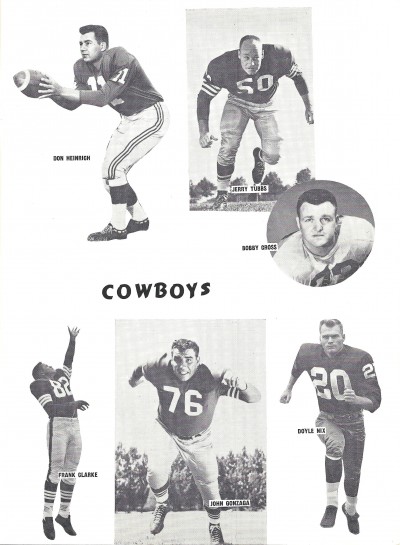

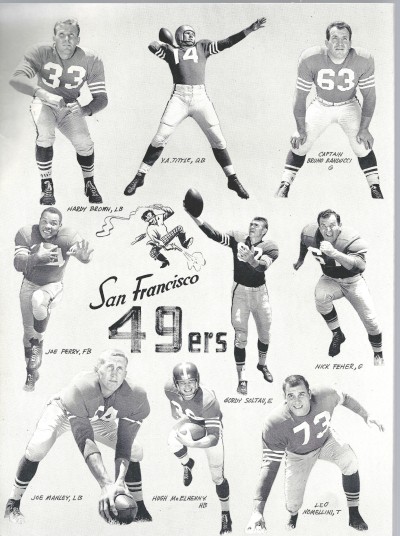

It also included one other distinction: When the expansion Dallas Cowboys made their world premiere Aug. 6, 1960, in a preseason game against Hugh McElhenny’s 49ers at Husky Stadium, Heinrich became the first quarterback in franchise history.

Heinrich, who moved from New York to Dallas in an expansion draft to stock the NFL’s 13th franchise, played the first half while former teammate McElhenny played in the first quarter, gaining nine yards.

The game, played in front of 22,000 at Husky Stadium, was the sixth NFL contest sponsored by Greater Seattle Inc., organizer of Seafair, and was part of Seattle’s effort to land an NFL franchise. After Seattle finally received an NFL franchise in 1974, the Seahawks made Jack Patera their first head coach. Patera played for the Cowboys in the Aug. 6 preseason game at Husky Stadium.

After finishing his career with Oakland in 1962, Heinrich held coaching positions with the Cowboys, Giants, Saints, Rams, Steelers and 49ers. While with the 49ers in 1974, he became acquainted with Kent State head coach Don James during San Franciscos preparations for the NFLs Hall of Fame game in Canton, OH. Heinrich immediately became enamored with James.

Later that winter, after Jim Owens resigned as UW coach, Heinrich telephoned UW athletic director Joe Kearney and recommended James as Owens replacement.

His (James) was the first name to pop into my mind, said Heinrich. I mentioned this to a number of people. I told Kearney he should look at James very carefully.

Kearney did and hired James, making Heinrichs phone call his greatest gift to the UW.

Two years into the James era (1976), Heinrich joined KIROs Pete Gross on Seahawks radio broadcasts, a position he held through 1981. After a broadcasting stint with the 49ers, Heinrich returned to the Northwest to team with Barry Tompkins on Huskies radio broadcasts.

Personable and knowledgeable, Heinrich became such an accomplished broadcaster that HBO and Prime Ticket hired him to do non-football events, including two world boxing title fights.

Heinrich was selected the quarterback on Washingtons all-time team in 1990, chosen over the likes of Bob Schloredt, Sixkiller and Warren Moon, and entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1987.

In June, 1991, Heinrich learned he had pancreatic cancer and had roughly four to six months to live.

Its devastating, Heinrich said when he heard the verdict. But I refuse to let it beat me down.

But it did, taking the Husky great Feb. 29, 1992, at his home in Saratoga, CA. Following memorial services in Saratoga and Seattle, McElhenny and Frank Gifford, a Giants teammate, spent two hours on KIRO-AM recalling their experiences with Heinrich.

One of my all-time best friends, Gifford said. Just a great guy.

We became very, very good friends, said McElhenny, and over 40-some years weve gone through some trials and tribulations. But no matter what, both of us were there for each other.

——————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

5 Comments

I was an entreing freshman at the UW in 1951 and had great hopes for the Henrich-McElhenny Huskies. However, Heinrich’s pre-season injury—tackled by an overzealous frosh—ended the team’s Rose Bowl hopes. McElhenny did, of course, make a memorable 100-yard punt return against USC that Frank Gifford, who played for USC that day, later said was the greatest single feat he had witnessed in a long college/pro career. It was a rainy day at Husky Stadium and just about every USC player had a shot at McElhenny, and missed, during the course of his run.

There was another post-season game involving McElhenny and the Seattle Ramblers.

After his final college game, McElhenny accepted an invitation to play for the Ramblers in a charity game against a pickup Bellingham semi-pro team on a damp and windy day at Battersby Field in Bellingham. A capacity crowd showed up. The Bellingham team upset the Ramblers but McElhenny excelled as usual. He was pulled from the lineup in the final minutes and ran a lap around the field, holding his helmet aloft, while the crowd cheered.

Today, of course, no agent would allow his NFL first-round client to play in a meaningless charity game and risk injury.

At the end of the 1950s I was living in NY when Heinrich was starting QB for the NFL

Giants. Typically, Heinrich would start the game, feel out the defense, and make way for Conerly from the second quarter onward. Heinrich was a smart QB and a good

short-route passer but lacked the cannon arm we see in some many QBs today.

Thanks, David and Steve, for these continuing pieces about former local sports heroes.

They were important in their time and are unfamiliar to many of today’s fans.

I was an entreing freshman at the UW in 1951 and had great hopes for the Henrich-McElhenny Huskies. However, Heinrich’s pre-season injury—tackled by an overzealous frosh—ended the team’s Rose Bowl hopes. McElhenny did, of course, make a memorable 100-yard punt return against USC that Frank Gifford, who played for USC that day, later said was the greatest single feat he had witnessed in a long college/pro career. It was a rainy day at Husky Stadium and just about every USC player had a shot at McElhenny, and missed, during the course of his run.

There was another post-season game involving McElhenny and the Seattle Ramblers.

After his final college game, McElhenny accepted an invitation to play for the Ramblers in a charity game against a pickup Bellingham semi-pro team on a damp and windy day at Battersby Field in Bellingham. A capacity crowd showed up. The Bellingham team upset the Ramblers but McElhenny excelled as usual. He was pulled from the lineup in the final minutes and ran a lap around the field, holding his helmet aloft, while the crowd cheered.

Today, of course, no agent would allow his NFL first-round client to play in a meaningless charity game and risk injury.

At the end of the 1950s I was living in NY when Heinrich was starting QB for the NFL

Giants. Typically, Heinrich would start the game, feel out the defense, and make way for Conerly from the second quarter onward. Heinrich was a smart QB and a good

short-route passer but lacked the cannon arm we see in some many QBs today.

Thanks, David and Steve, for these continuing pieces about former local sports heroes.

They were important in their time and are unfamiliar to many of today’s fans.

Thanks very much Ted. Your recollections are always personal and interesting, and terrific additions to our posts.

Thanks very much Ted. Your recollections are always personal and interesting, and terrific additions to our posts.