By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Joe Mooney, the late Seattle Post-Intelligencer sports scribe who had a wonderful knack for banging words together, once wrote, “The Washington State Cougars go to the Rose Bowl like clockwork on the 16th and 30th years of every century.” Referencing their 1916 and 1930 appearances, Mooney penned that in the early 1980s, long before the Cougars won trips to the 1998 and 2003 Rose Bowls, but his point is still valid: Washington State and Pasadena go together, as Mooney also wrote, “like ketchup and waffles.”

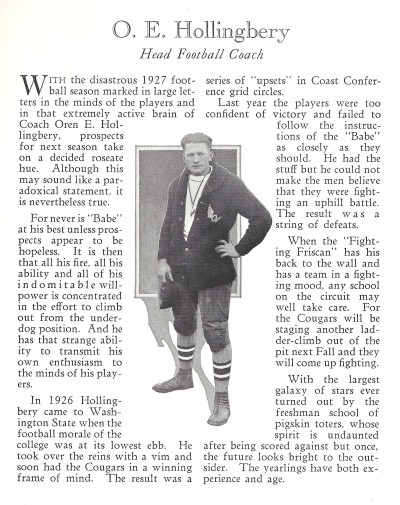

But back in Babe Hollingbery’s day (1926-42) that wasn’t necessarily the case. Although Hollingbery took the Cougars to Pasadena just once (1930), he had them sniffing roses five other times – 1932, 1934, 1936, 1941 and 1942 — with second-place Pacific Coast Conference finishes.

Washington State won 93, lost 53 and tied 14 during the Hollingbery era, the longest run of sustained success in WSU football history, during which the Cougars had just two losing seasons.

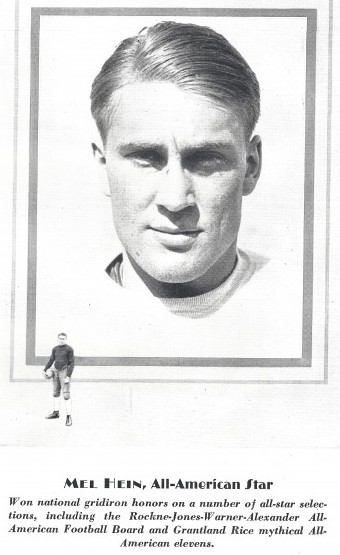

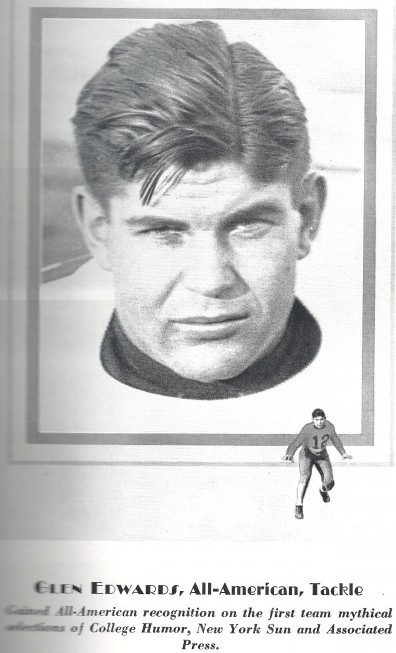

Hollingbery’s 1930 team, which went 9-0, shutting out five opponents, before losing to Alabama in the 1931 Rose Bowl, remains one of the best in school history and above all others in this regard: It is the only edition of the Cougars to feature two consensus All-America selections who later became members of the College Football Foundation Hall of Fame and Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Hollingbery recruited Mel Hein and Glen “Turk” Edwards, getting Hein out of Burlington-Edison High School in Burlington, WA., and Edwards out of Clarkston (WA.) High School. Hein arrived on the Pullman campus in 1927, Edwards in 1928. It’s hard to imagine two more decorated teammates, and that would include Hugh McElhenny and Don Heinrich (1949-51) of the Washington Huskies (see Wayback Machines: McElhenny’s 100-Yard Punt Return and ‘Deadeye’ Don Heinrich).

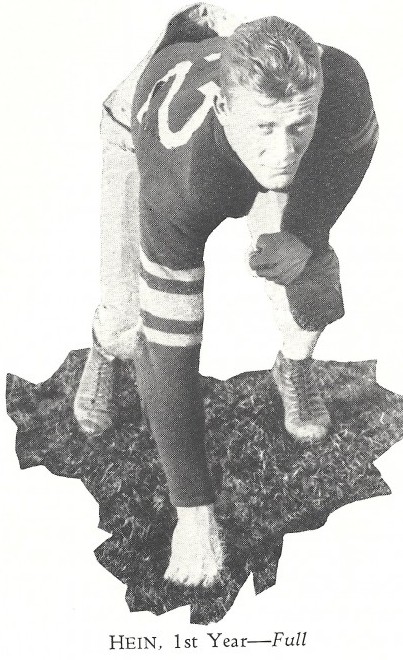

Born Aug. 22, 1909 in Redding, CA., 6-foot-2, 225-pound Melvin Jack Hein initially expressed interest in becoming a rower, but gravitated to football and basketball when he discovered how good he was at those sports.

Hein caught Hollingbery’s attention when he played center and defensive lineman for the Burlington Tigers. As a senior, Hein earned the Skagit County Football MVP award, the highest accolade for a prep player in the Skagit Valley in those days. He was also named first-team All-State as a senior.

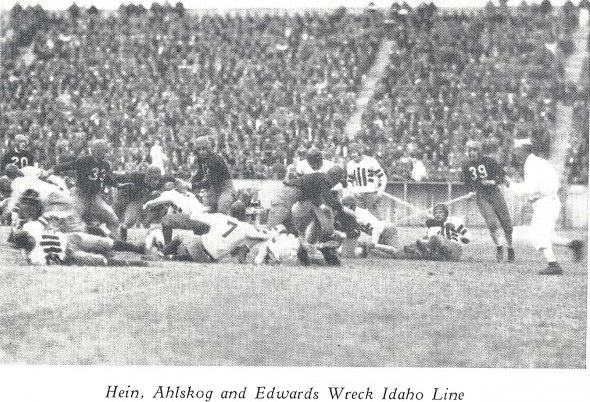

Hein played all three interior line positions at Washington State from 1928 through 1930 and captained the 1931 Rose Bowl team. During Hein’s tenure, WSU went 26-6, winning 15 of the 26 by shutout. Also a center on Jack Friel’s basketball team and winner of the javelin at the 1931 Drake Relays (199-9), Hein made Grantland Rice’s All-America team and first-team All-Coast after playing virtually every minute of every game.

Since the National Football League did not have a draft in those days, Hein took it upon himself to make his own way in the pros, writing letters to three teams, offering his services. He did not hear back from the Portsmouth Spartans (forerunner of the Detroit Lions, who employed former WSU teammate Elmer Schwartz) but did hear from the Providence Steamrollers, who sent him a contract offering $125 per game.

Hein signed the contract and mailed it back. The next evening, he ran into Ray Flaherty, a New York Giants receiver (1923-25), who had played football at Washington State and Gonzaga, at a Cougars basketball game in Pullman. Flaherty told Hein that the Giants had just mailed him a contract offering $150 per game.

Hein hastily wired the Providence, RI., postmaster, described his letter to the Steamrollers, and asked that the postmaster return it. For whatever reason, the postmaster violated regulations and sent the contract to Hein, who destroyed it. With that, the Giants got one of the greatest players in NFL history.

Hein married his college sweetheart, Florence, shortly after he sent his contract to the Giants. The pair packed their belongings into a broken-down car and drove from Pullman to New York.

Listed third on the depth chart when he reported, Hein got his chance to play when both of New York’s veteran centers were injured, reducing the pair to a Wally Pipp fate. Hein made second-team All-Pro his first two seasons and was widely considered the best player in the league every year after that.

He made first-team All-Pro for the first time in 1933, played in the famous “Sneakers Game” in 1934 (Flaherty suggested the Giants wear sneakers for better traction on the frozen Polo Grounds surface), and became renowned for his durability, acquiring the nickname “Old Indestructible,” in 1935, his first year as Giants captain.

“Hein was one of the most durable players in NFL history,” The Pro Football Hall of Fame wrote in Hein’s official biography. “In the early days, there was no platoon football and players went 60 minutes every game. Yet Hein called for a timeout just once in his career — for hasty repairs to a broken nose in 1941. It marked the only time Hein was removed from a game because of injury in 15 seasons of professional football.”

To illustrate Hein’s importance to the Giants, coach Steve Owen created what was, effectively, a two-platoon system in 1937 so that separate teams played offense and defense. Each unit had 10 men plus Hein, the only man to go both ways. As Owen explained, “Hein was too good to take out.”

“Even in his final campaign at 36, Mel was still playing every game from the first kickoff to the final gun,” added the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “Mel combined great stamina, a cool head, mental alertness and simply superior ability to become an exceptional star.

“He was named first-team All-NFL center eight straight years from 1933 through 1940. He also earned second-team All-NFL recognition five other times. In 1938, he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player, a rare honor for a center (no interior lineman has won it since). He was the team captain for 10 seasons.”

Hein helped the Giants win the league title in his MVP season for the second time (also 1934). Hein also led the Giants to five other championship-game appearances, in 1933, 1935, 1939, 1941 and 1944.

“Hein could do everything expected of a center and a linebacker and quite a bit more,” The Pro Football Hall of Fame continued. “Mel was one of the few NFL stars who had the speed (he once returned an interception 50 yards for a touchdown against Green Bay) and agility to contain Green Bay’s premier receiver, Don Hutson, by bottling him up on the sidelines so he could not maneuver into the open. Although Mel was thoroughly aggressive and coldly ferocious when it came to blocking and tackling, he was a gentleman player. He rarely lost his temper.”

“He was the surest, cleanest and most effective tackler I ever encountered,” fellow Hall of Famer Bronko Nagurski told The New York Times.

Virtually impossible to get past on offense and all but unblockable on defense, Hein has been widely described as the greatest center to play the game. The Giants owner, Wellington Mara, who grew up awed by the great 1930s teams of his youth, once called Hein the No. 1 player of the team’s first 50 years.

“From the time the big All-American from Washington State stepped onto the field in a Giants uniform for the first time in 1931 until he retired at the end of the 1945 season, he was a legend to Giants players, coaches, fans and opponents,” wrote The New York Times in 1992. “If there has been an equal since, it is Lawrence Taylor.”

Even Taylor didn’t do this: Hein announced his retirement after the 1941 season in order to coach at Union College in Schenectady, NY., but the Giants persuaded him to keep playing because of a World War II manpower shortage. For the last four years of his career, Hein coached in Schenectady during the week, then played for the Giants on Sunday without practicing.

Hein entered the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954 and became a charter member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963. In 1969, Hein was named the center on the NFL’s 50th Anniversary Team, and that same year was voted one of the 11 all-time best professional and collegiate football players in a vote conducted in conjunction with professional football’s Centennial. In 1994, Hein made the NFL’s 75th Anniversary Team. Hein is also the center on the All-Decade Team of the 1930s.

In 1999, despite 55 years having passed since his final game, The Sporting News ranked Hein No. 74 on its list of the “100 Greatest Football Players of All-Time.”

Every Hall of Fame for which Hein is eligible has inducted him. He made the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 1961, the Inland Empire (Spokane) Sports Hall of Fame in 1963, and the WSU Athletic Hall of Fame in 1978. Hein is also a member of the Washington Interscholastic Athletic Association (WIAA) Hall of Fame (2004) and Burlington-Edison Hall of Fame (2006).

After retiring from pro football in 1945, Hein became a full-time line coach. He worked for several pro teams, including the New York Yankees, Los Angeles Dons and Los Angeles Rams, and spent 15 years as an assistant at USC, where for many years he worked alongside Al Davis, future owner of the Raiders.

“He was truly a football legend and a giant among men,” said Davis. “Mel was one of the greatest football players who ever lived.”

Davis hired Hein in 1965 to supervise American Football League officials. After the merger of the AFL into the NFL in 1970, Hein served as supervisor of officials for the American Football Conference until his retirement in 1974.

The Washington State Board of Regents honored Hein May 14, 1983, with its Distinguished Alumnus Award, the highest accolade that can be bestowed a WSU alum.

By the time WSU feted Hein, he had retired to San Clemente, CA. He died there Jan. 31, 1992 of stomach cancer at age 82.

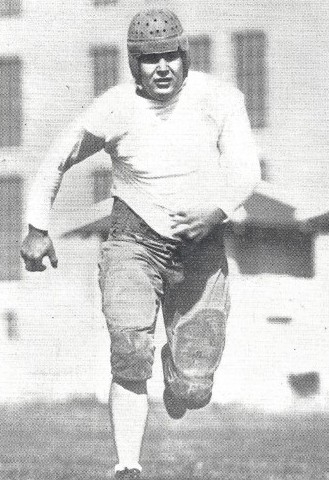

After Albert Glen Edwards, born Sept. 28, 1907, in Mold, WA., left WSU in 1931, five years before the first NFL draft, he received offers from three franchises, the Boston Braves, New York Giants, and Portsmouth Spartans. Edwards could have joined Hein, but chose the highest bid –- $1,500 for 10 games from the Braves, a team that would later become the Boston Redskins and then move to Washington D.C. in 1937.

Edwards, who earned All-NFL honors every year of his career (first-team All-NFL in 1932, 1933, 1936, 1937) except the last one, didn’t spent nearly as much time with the Braves/Redskins (nine seasons) as Hein did with the Giants, but, like Hein, played every minute of every game.

For most of his tenure with the Redskins, Edwards played for Spokane native Ray Flaherty, who became Boston’s coach in 1936. Edwards also served as an assistant under Flaherty (1941-42).

A 6-foot-2, 255-pound tackle would go unnoticed in today’s football landscape, but in Edwards’ time a player of that size stood out like Haystack Rock. Oddly, Edwards’ career came to an end due to an injury that did not even occur during a game.

Prior to a meeting with the Giants in 1940, Edwards, the Redskins’ captain, went to the center of the field for the coin-toss ceremony. Representing New York: Edwards’ former Washington State teammate Hein.

After shaking hands with Hein, Edwards attempted to pivot around to head back to his sideline. However, his cleats caught in the grass and his knee gave way, ending his season and ultimately his career.

Edwards continued with the Redskins as an assistant coach from 1941 to 1945 and as head coach from 1946 to 1948, leading a team quarterbacked by Sammy Baugh (16-18-1). Then, after 17 seasons in the club’s employ, Edwards retired and returned to the Pacific Northwest.

For a number of years, Edwards sold sporting goods out of a store in Seattle’s University District. In 1961, he relocated to Kelso, where he spent 12 years working in the Cowlitz County assessor’s office.

Edwards entered nearly as many halls of fame as Hein, including the Inland Empire (1966), State of Washington (1968), Pro Football (1969) and College Football (1975).

Edwards died in Kirkland Jan. 12, 1973 after a long illness. He was 65.

Born July 15, 1893 in Hollister, CA., Orin E. “Babe” Hollingbery coached WSU for more than a decade after Hein and Edwards left school. While his 1930 team ranked as his best, Hollingbery won a lot of games without the future Hall of Famers.

Hollingbery was a fascinating guy. He never attended college and spoke with a stammer, but almost always wore a tie, even at practice. He also had a photographic memory that allowed him to almost instantly recognize how a play went right or wrong.

Hollingsbery grew up in San Francisco, lettered in five sports at Lick High School, and developed into an outstanding bowler, golfer and trapshooter. After high school, Hollingbery coached high school football in the San Francisco area and played and coached at San Francisco’s Olympic Club.

Hollingbery had legendary energy. One fall, during his prep coaching days, he directed three football teams, riding his motorbike from practice to practice. His success with the Olympic Club caught the eye of Washington State administrators.

A year before he arrived in Pullman, and while still the Olympic coach, Hollingbery helped organize the first East-West Shrine All-Star game, played Dec. 26, 1925. Hollingbery remained associated with the charity contest throughout his coaching life, serving on the West staff, as head coach or assistant, for the first 18 Shrine games, lasting through Jan. 1, 1943.

The man who directed Cougars football from the mid-1920s through the Great Depression and into World War II had a formula he never changed: follow the rules, run the single-wing and win. The rules included no drinking, no smoking, no cussing. If a Cougar player broke a rule, and Hollingbery found out about it, Hollingbery threw him off the team.

When, according to The Seattle Times, WSU end Nick Susoeff puffed on a cigarette on the steps of the campus post office in 1942 and saw the Washington State football coach driving toward him, he acted fast. Susoeff turned, chewed up the smoke and swallowed it.

When Washington State took a two-year football hiatus for World War II (1943-44), Hollingbery moved to Yakima and started a hops brokerage, Hollingbery & Son, which worked directly with growers and dealers to provide hops of the highest quality for customers.

Following the war, Hollingbery and WSU administrators could not come to terms over a salary and so the greatest coach in Cougar football history returned to Yakima and built what became a very successful hops business.

Hollingbery suffered a stroke Dec. 23, 1973 that left him in a coma until Jan. 12, 1974, when he died at Yakima’s St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Hollingbery was 80.

Hollingbery coached longer (17 seasons) and had a better winning percentage (.637) than any football coach in WSU history. He did not lose a home game until nearly midway through his 10th season, remarkable considering that Hollingbery didn’t inherit a strong program. When he took over in 1926, the Cougars had won only six games in the three previous years.

Hollingbery entered the Helms Foundation Hall of Fame in 1961, the State of Washington hall in 1962, and the WSU hall in 1978, a year before his induction into the College Football Hall of Fame. He is buried at Terrace Heights Memorial Park in Yakima.

———————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com