By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Imagine the clout that a sports executive would wield today if he not only owned his own ball club, but personally acquired its players, made every trade, negotiated business contracts, hired and fired front-office personnel, set ticket prices, collected gate receipts, controlled the flow of information about the team, and occasionally filled out the lineup card.

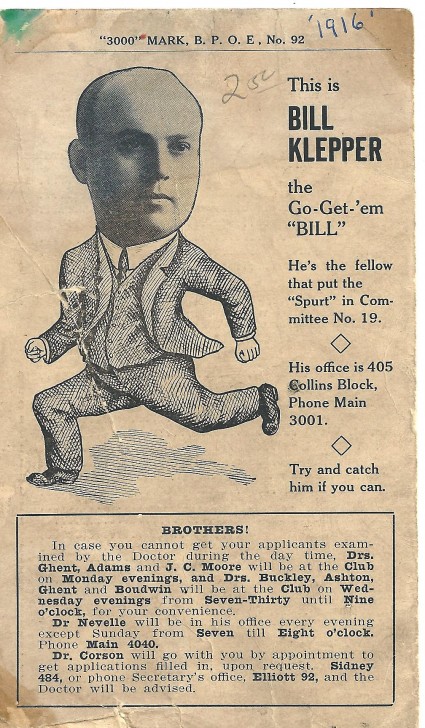

A phalanx of suits would collaborate on those responsibilities now, but in William Haskel Klepper’s time – the Roaring Twenties through the Great Depression — he was a one-man orchestra. The Oregonian described him as “the Bill Veeck of the Pacific Coast League before there was a Bill Veeck,” and he lived a large irony: Klepper rarely had two nickels to rub together.

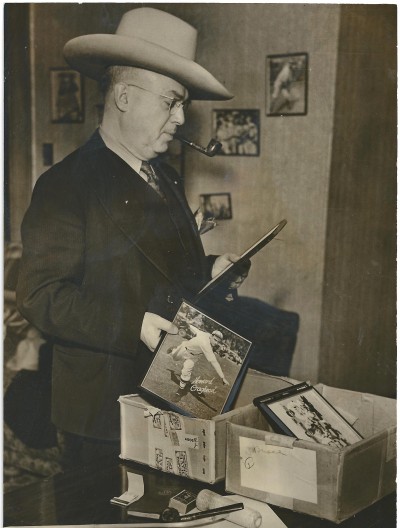

Klepper never made much money as a public relations flak, his first gig, or later as a clothes salesman specializing in men’s suits and hats, or even as a part-time real estate broker, specializing in single-family bungalows.

But Klepper used other people’s money, a lot of showmanship, keen baseball knowledge and a bent for penny pinching to parlay his particular brand of gab into two tenures as owner and chief operator of the Seattle Rainiers/Indians and Portland Beavers.

Klepper’s name hasn’t appeared in public prints with any regularity in more than a half a century, but he was correct in 1946 when he said that in his heyday, few people came under as much public scrutiny as as he did.

“Perhaps a lot of them were knocks,” Klepper told The Oregonian late in his baseball career, “but no man other than the President of the United States has had as many words written about him in Pacific Coast newspapers as I have. I certainly furnished a lot of copy, though a lot of it wouldn’t make good reading for my grandson, Jackie.”

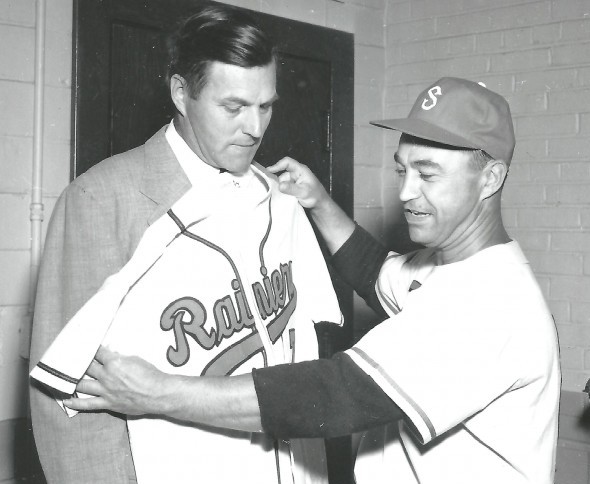

Klepper was largely forgotten when he died in 1959, and the ensuing years have done little to revive his memory. On the occasions his name has surfaced, it has usually been in connection with his passing off the ownership of the Seattle Indians in late 1937 to Emil Sick, who renamed the club the Rainiers and turned them into the kind of winners Klepper only dreamed about.

In almost all accounts of his sale of the team to Sick, Klepper is portrayed as the steward of a ragtag franchise always on the verge of bankruptcy, and as a notorious tightwad and tax dodger who ran the Indians into financial ruin.

The truth is not quite as simple as that. If Klepper hadn’t operated the Indians during the Great Depression, or if he’d come to baseball with the financial wherewithal that Sick possessed, Klepper might not have absorbed such a public relations hit. Even with the disadvantages he faced, Klepper was not only one of the Northwest’s most significant baseball figures between Dan Dugdale and Sick, he kept baseball going in Seattle and Portland when a lesser man might have quit.

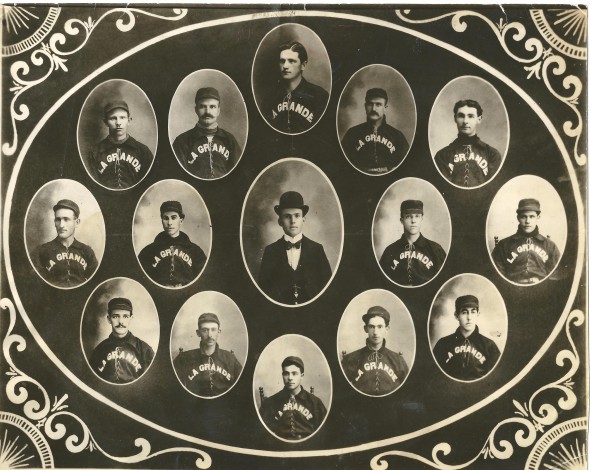

Klepper was born in Washington Territory in 1878 and sold suits and hats as a young man. His public profile began to emerge in 1915 when The Seattle Times referenced his activities as a “prominent member” of the Seattle Elks Club (Lodge 92) and as “Sports Director” of the Seattle Parks Department.

In 1918, Klepper gained additional exposure when he worked as campaign manager for A.E. McNeen, Seattle’s chief deputy treasurer, in his race to become the King County treasurer. By 1919, Klepper had become secretary-treasurer of the Seattle Baseball Club, the first incarnation of the Rainiers.

When, at the end of 1919, James Brewster, majority owner and president of the Rainiers (Brewster had purchased majority interest from Dugdale for $60,000) announced he would not be able to continue his presidency for the 1920 season due to the press of private business – Brewster was building what would become a string of highly successful Seattle cigar stores — Klepper was appointed to take his place.

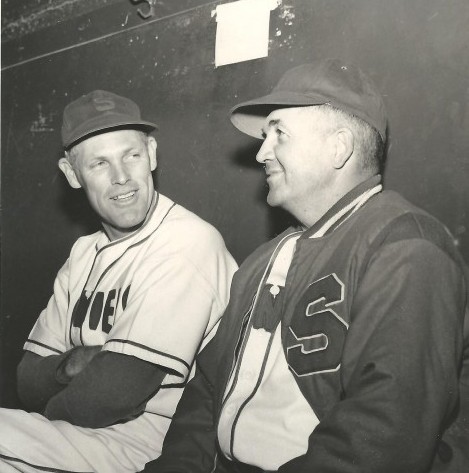

“He’s small, portly, pudgy, dapper, and slightly bald, and is referred to by his friends as “Bald Bill,” The Seattle Times wrote after Klepper assumed Brewster’s duties.

A year later, using borrowed money, Klepper acquired his own stake in the franchise, which Dugdale had forsaken after concluding that professional baseball had no viable future in Seattle (see Wayback Machine: Seattle Struck Gold In Dugdale).

Klepper never had much operating money, reducing him to frequently low-balling players and managers at contract time. In 1920, for example, Klepper and his new manager, Buzzy Wares, became embroiled in a money squabble and Wares held out, insisting he preferred to remain in Hanford, CA., and run his billiards parlor rather than manage the club at Klepper’s price.

Klepper won that battle and Wares returned to Seattle to manage the club, only to have Klepper replace him a year and a half later with a cheaper skipper, Bill Kenworthy, the team’s second baseman.

After the Rainiers went 102-91 in 1920 (second place) and 102-83 (fourth) in 1921, James R. Boldt, a Seattle restaurant owner and concessionaire, purchased the majority of the team’s stock from Brewster and George Hardenbaugh, effectively forcing Klepper to sell his shares (Boldt retained control until 1923, when, after losing $25,000, he sold the team to Los Angeles Angels manager Red Killefer and Angels business manager Charles Lockard).

Klepper used his proceeds to purchase, for $150,000, a controlling interest in the Portland franchise from the McCredies, Judge W.W. and his nephew, Walter H. Klepper quickly cast aside Walter, long-time Beavers manager, in favor of Tom Turner, a 34-year-old protégé of Connie Mack.

Klepper’s motive: He considered Turner’s connection to Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics the key to turning around the Portland franchise, which had been a disaster in the final days of the McCredie ownership.

After the transaction, on Oct. 21, 1921, The Oregonian, profiling the team’s new owner, wrote, “Mr. Klepper has had perhaps the most remarkable career of any club executive in the history of minor league baseball. In two years in Seattle, he made his fame as a trader in baseball players known from one end of the continent to the other.

“It has often been said of Klepper that even if no turnstile clicked off a quarter at the entrance to the grandstand he could still return dividends on the sale of players to the major leagues. In respect to his dealings with the major league clubs, he has turned deals beyond the power of conception of even the most experienced of club presidents.

“William Wrigley, the chewing gum king who owns both the Chicago National League and Los Angeles Coast League clubs, offered Klepper the presidency of the Los Angeles club if he would change his residence, but the Seattle man turned down the offer.

“The Seattle baseball club is one of the best-known in the United States. In 1920, its attendance record exceeded that of any other club in the country with the exception of that of Baltimore, which has double the population of Seattle.

“The Seattle club in the last two years has sent such ballplayers as Sammy Bohne, Bill Cunningham, Lyle Bigbee, Bob Geary, Herb Brenton, Ray Francis and Carter Elliott to the majors, all for handsome profits.”

(Bohne played seven years in the majors, mostly with Cincinnati; Francis played three seasons and got into a much-publicized brawl with Ty Cobb.)

When Klepper arrived in the Rose City, he brought with him the aforementioned Kenworthy, a move that soon erupted in controversy. Kenworthy had not only played second base in Seattle but managed the Rainiers in 1921, and Klepper wanted him to fill both roles in Portland.

Simultaneously, Boldt wanted Walter McCredie to become field manager in Seattle. What Boldt didn’t know was that Klepper and Kenworthy had an agreement they felt would make Kenworthy a free agent and thus eligible to join Klepper in Portland: Kenworthy would refuse all contract offers from Seattle, thereby making him a free agent on the basis that “he and Seattle could not come to terms.”

As soon as Boldt hired McCredie, Kenworthy asked the National Board of Arbitration to declare him a free agent. The National Board of Arbitration denied Kenworthy.

But Boldt did not want an unhappy Kenworthy, Seattle’s best player in 1921, sitting in the Rainiers dugout. So he proposed to Klepper that Seattle trade Kenworthy to Portland for Marty Krug. The deal was made and everyone was happy – except Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who suspended Kenworthy pending a review of the matter.

Landis, who had just tossed out eight men out for their roles in the Black Sox scandal, deemed Klepper guilty of tampering and barred him from any involvement with the Beavers for three years and gave Portland’s vice-president, Seattle cigar store magnate James Brewster, a two-year suspension.

According to The Portland Beavers, a book by Kip Carlson and Paul Andresen, “The feisty Klepper went to court and had the decision overturned, supposedly the only time that Landis ever had a baseball ruling reversed.”

While Klepper fought his banishment through legal channels, he received one concession from Landis: He could perform administrative duties on behalf of the franchise but had to recuse himself from baseball matters. According to Seattle Times baseball writer Alex Schults, Klepper continued to run all aspects of the franchise “from the background.”

Certainly Portland’s signing of Jim Thorpe in 1922 qualified as a baseball matter, and Klepper, who also helped Tacoma acquire a franchise in the Western International League in 1922, was heavily involved in Thorpe’s signing, a move Klepper made to boost the Beavers’ poor attendance.

Klepper also negotiated the famous Carlisle Indian’s contract, which paid the Olympic legend $1,000 per month, a princely sum on those days. Nearing the end of his career, Thorpe saw action in 35 games for the Beavers, batting .308.

The Kenworthy episode nearly cost Klepper his stake in the Portland franchise. In a vote of PCL directors to determine whether Klepper should stay or go, eight owners deadlocked 4-4, narrowly allowing Klepper to remain.

Klepper’s stayed in Portland until 1925, when he received an offer too good to pass up. A year earlier, Klepper signed a promising young catcher named Mickey Cochrane away from Class D Dover in the Eastern Shore League. When the Philadelphia Athletics decided they had to have Cochrane, Klepper told owner Thomas Shibe and manager Mack that if they really coveted Cochrane, they had to buy the whole franchise. They did, and the sale was recorded Nov. 1, 1924.

A year later, with Klepper temporarily out of baseball, Cochrane began a 13-year, major league career that culminated in his Hall of Fame induction in 1947.

Three years after selling the Beavers to Mack’s Athletics, Klepper, along with Dr. Earl V. Morrow of Portland (“a thirty-second degree Mason, a Shriner, a past exalted ruler of the Elks and one of the first appointees of the Oregon Boxing Commission”) and John Savage, owner of Seattle’s Butler Hotel, re-acquired the Indians and Dugdale Park from Killefer and Lockard by purchasing their stock (see Wayback Machine: Red Killefer’s 1924 Indians).

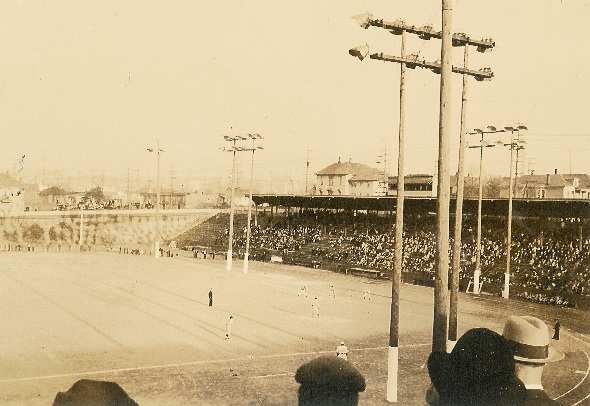

Klepper announced he would build a new facility to replace Dugdale Park, which Dugdale had constructed in 1913 as the new home for his 1912 Northwest League champion Seattle Giants (see Wayback Machine: ‘Seattle’ Bill James And The 1912 Giants).

According to a Times interview with Klepper, the new park would seat 25,000, feature a stucco exterior with wooden grandstands and bleachers reinforced with concrete and steel, and would be just outside the downtown business district (no specific address given).

Klepper also informed the Times that he had already purchased the property and obtained construction financing, but not a shovel’s worth of dirt was turned to build the park, an apparent victim of the Great Depression.

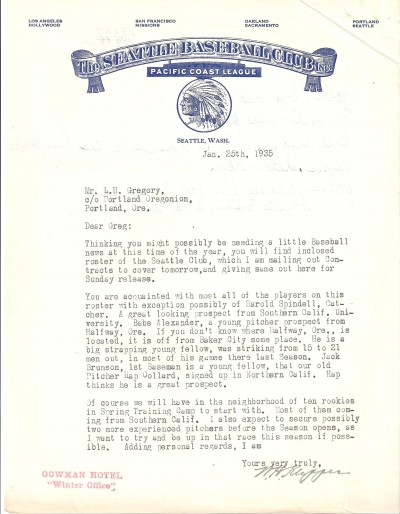

Klepper, who ran the Indians from an office in the Gowman Hotel (Second and Stewart) ultimately got a new park, but not the one he envisioned.

Shortly after midnight on July 4, 1932, Dugdale Field burned to the ground. Investigators originally couldn’t determine if the cause was arson or accident, but eventually Robert Driscoll confessed he had torched the place, along with 115 other establishments around the city, including Seattle’s largest macaroni factory (see Wayback Machine: A Fire That Changed Our Sports).

With Dugdale Park gone, the homeless Indians were forced to move across town to Civic Stadium, an unappealing dirt football field on lower Queen Anne built in 1928 that was in no way suitable for baseball (several visiting players refused to play in the facility).

Klepper found that making money at Civic Stadium was next-to-impossible, especially with a second-division team and an odious lease agreement in the throes of the Depression. When when the Indians moved into the facility, Klepper discovered the City of Seattle had a deal in place with Boldt giving him all concessions rights, and Boldt refused to share his profits with the baseball club. Things got so bad for Klepper that, at one point, he ran out of money to pay his players.

“We had gone about a month and a half without a payday and we had a big day on a Sunday with a big crowd,” said pitcher Paul Gregory. “We went out and took infield practice, then we all went back into the clubhouse and put on our ‘sit clothes’ and went up and sat in the stands.

“Klepper came rumbling down wondering what was the matter. We explained to him that we hadn’t been paid and weren’t going to play unless we were. So he sent us back to the clubhouse and brought two or three sacks of money down and paid us off. I often said that was the first and the shortest strike in baseball.”

Klepper used his wits to keep the Indians both alive and competitive, and had, if nothing else, a profound ability to identify and acquire talent, as The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported:

“In the late 20s and early 30s,” the newspaper explained, “Klepper made several trades with his old club, Portland, and always got the better of them. He made them with Tom Turner, president of the Beavers (whom Klepper hired after he bought the Beavers).

“First, Klepper sent pitcher Jack Knight to Portland for Bert Cole and talked Turner into tossing in Dave Barbee. Neither Cole nor Barbee did the Indians a lot of good, but either was worth more than Knight.

“Next, Klepper sent Gomer Wilson, a worthless southpaw, to Portland for Fritz Knothe, a good infielder. When Turner wasn’t satisfied, Klepper swapped him Billy Olney, a rookie first baseman, for Wilson. Olney didn’t last the season. Then Klepper cooked up a three-cornered deal whereby Andy House went to Portland, Joe Cascarella to Baltimore and Stuffy Stewart came to Seattle. House was released outright by Portland.”

Klepper’s eye for talent is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that six of the 10 members of the Rainiers Roll of Honor (Kewpie Dick Barrett, Bill Lawrence, Dick Gyselman, Mike Hunt, Hal Turpin and Alan Strange), determined by a 1954 fan vote, were signed to Seattle contracts by Klepper. In that respect, Emil Sick purchased a windfall in 1938 when he took over the club.

But Klepper couldn’t assemble enough good players at any one time to make a difference, nor could he overcome Civic Stadium’s problems and his unfavorable lease. During the 10 seasons between 1928 and 1937, the Indians had only one winning year (93-82 in 1936), lost more than 100 games six times, never finished higher than fourth, and four times finished eighth. Klepper ran through six managers during the span.

Symptomatic of the ills that plagued the franchise was a head-slapping 1934 incident. With Dutch Ruether managing the Indians, Sacramento came to town for a seven-game series. Klepper was out of town on business and, during his absence, Ruether and Sacramento owner Lew Moreing decided to combine a couple of single night games into an afternoon doubleheader, which might have been a good idea except they forgot to tell anyone about the switch and the papers came out without a word about it.

When the doubleheader started far earlier in the day than the public figured it would, just one person had paid for a grandstand seat while three others had paid for bleacher seats. By the end of the first game, Ruether and Moreing could count three grandstand patrons and four bleacher patrons for a total of seven. In other words, a game with virtually no revenue.

Between 1934-37, Klepper’s main job involved keeping the Indians out of bankruptcy court. The underfunded club stumbled to such an extent that, late in 1937, both Seattle newspapers, The Times and Post-Intelligencer, began to lobby for new ownership. The Times offered up its candidate to lead the franchise, boxing promoter Nate Druxman (see Wayback Machine: Nate Druxman, Mr. Boxing).

“Put him at the lead of the organization, if he’ll accept the responsibility,” opined The Times. “Or try to find someone else as capable. Druxman is baseball-minded from his old semipro days, so probably would love the trust. Druxman has made a brilliant success of boxing, has given several Northwest youngsters chances at world championships and brought Seattle favorable publicity because of his ‘fistic gigantics.’

“Seattle wants better baseball than it’s getting. It wants a modern baseball plant, where the Indians could be presented. The Klepper regime cannot be ousted by conversation, but a new baseball ship could be launched by a real organization backed by real money.”

Klepper never had “real money,” and, in fact, didn’t even have enough to pay local tax collectors. In the most infamous day in franchise history — Sept. 20, 1937 – a half dozen local and federal agents, on a mission to collect thousands of dollars in unpaid admissions taxes, stormed Civic Stadium and demanded the day’s gate receipts while threatening to break down the box-office door.

On the same day, Klepper fired manager Johnny Bassler for insubordination for allowing Dick Barrett to hurl both games of a doubleheader. Barrett won both and earned a $500 bonus, $250 of that for reaching 20 wins.

Klepper had told Bassler to pitch rookie Marion Oppelt in the second game to save a potential $250 bonus to Barrett, but Bassler refused and, during an clubhouse argument, shoved the owner. Royal Brougham reported in the next day’s Post-Intelligencer that Klepper ended an ignominious day with a “discolored eye, the result of an altercation with one of the Seattle players.”

Brougham also quoted Barrett to the effect that he would retire from baseball if the Klepper ownership continued in Seattle. Obviously, it couldn’t, and Klepper sold to Sick Dec. 15, 1937, after which Klepper returned to Portland to take over the Oregon distribution of Sick’s beer (see Wayback Machine: Seattle First Citizen Emil Sick).

“After fat years and lean, medium seasons and leaner ones, the Coast League presented Bald Bill with a $250 gold watch, suitably inscribed,” The Times wrote. “Needless to say, the reign of Klepper was a hectic one.”

Over the next several years, Klepper participated in Elks Club activities, joined the Shriners and served his Presbyterian Church. He also spent a lot of time watching the Beavers play, often sitting alone in their Vaughn Street ballpark.

In 1942, Klepper again purchased the Portland club, this time from E.J. Shefter. With more money at his disposal in a war-time economy, he put together teams that made three consecutive PCL playoffs (1943-45) and won the 1945 pennant. Klepper then sold his stake in the franchise to George W. Norgan of Vancouver, B.C., retired again (former Rainiers business manager Bill Mulligan took over his executive duties) and became a full-time real estate broker.

Klepper never entirely got sports out of his system. In 1950, he became general manager of the Oregon Jockey Club, a position he held for five years.

Klepper died shortly before midnight June 25, 1959 at Portland’s Emanual Hospital, seven months shy of his 81st birthday and three weeks after suffering a heart attack. He spent part of his final day listening to a radio broadcast of Portland’s 1-0 victory over Salt Lake City.

After Klepper’s death, Schults wrote in The Times, “Klepper’s career was one of the most spectacular in organized baseball.”

It might be more memorable today if Klepper hadn’t been so constrained financially, especially during the Depression years in Seattle. Given the economic gloom of that time, Seattle fans were fortunate that Klepper kept the franchise alive.

————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

1 Comment

David, I know this might be more suitable for a book than a column, but how about Royal Brougham? Or just Alice? Seems like every story you’ve done about early-day Seattle baseball has had at least one pic including Alice Brougham–well, at least the ones which include 1930s or 40s; I don’t recall seeing her pic from earlier days; not sure when she was born, but likely too young before the early 30s.

Royal himself would be a good book subject, I think. My mom knew him some during his last years at the P-I (she worked there too) and told me a few ‘Royal’ stories.