UW Rowing: Timeline / Numbers / Spreading Wealth / Windermere Cup

By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

On Saturday, May 7, the University of Washington will host the Windermere Cup for the 25th consecutive time. This year’s rowing festival on Lake Washington will include crews from Cambridge University, Oklahoma, Stanford and UW, and will help celebrate Seattle’s Opening Day of yachting season.

Although he died in 1950, William (Billy) Goodwin, an intriguing artifact from Washington’s athletic past, deserves some props here. More than 100 years ago (1889) Goodwin, then a newly graduated rower and track athlete at Yale, answered an ad in a New York newspaper offering “honest work to able-bodied young men willing to leave the East Coast, head west and help re-construct Seattle in the aftermath of a June 6 fire that reduced a huge chunk of the city to cinders.

Goodwin brought with him a rugby ball, rule book and the single scull he had rowed on behalf of Yale. Once encamped, Goodwin introduced University of Washington students to rugby (forerunner of American football) and rowing, and proposed that a team of Goodwin-assembled alumni from eastern colleges (Harvard, Yale and Brown) that had come to Seattle after answering the same newspaper advertisement he had, contest Washington students in rugby on Thanksgiving Day (1889).

The match came off as scheduled on Nov. 28, in a waterfront park located near the end of the Madison Street cable car line, marking the launch of what would become Husky football.

Less than a year later (1890), Goodwin organized the first international rowing race on the West Coast, featuring amateur clubs representing Seattle and Vancouver, and the first intercollegiate, four-oared boat race (unofficial) between the University of California and students from the University of Washington.

It took nearly a decade before UW adopted rowing as an “official” school sport (1901), at which point Goodwin’s involvement in athletics had largely ceased, while Hiram Conibear’s had started to ramp up.

Born Sept. 5, 1871, in Mineral, IL, Conibear attended the University of Illinois, spent two years as Director of Physical Culture at the University of Montana and two years in a similar capacity at his alma mater. Starting out as a cycling instructor, Conibear soon became a trainer for college athletes in a variety of sports, as well as a football and track & field coach.

In 1902, Conibear took a job as an assistant athletic director/trainer under Amos Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago. By 1906, Conibear held two positions. In addition to his work with Stagg, Conibear served as trainer for the Chicago White Sox, who defeated Frank Chance’s Chicago Cubs in that year’s World Series.

A one-time Yale divinity student, Stagg exerted a profound influence on Conibear, who shared Staggs relentless curiosity and out-of-the-box thinking. Primarily a football coach, Stagg invented (or would go on to invent) such staples as the man in motion, lateral pass, center snap, onside kick, Statue of Liberty play, unbalanced line, quick kick, quarterback keeper and linebacker position. Stagg became one of the first coaches to utilize the forward pass and develop concepts, still used today, for the passing game.

No college coach awarded varsity letters to athletes until Stagg did. Stagg introduced hip pads. For all of this, and more, Stagg eventually earned membership in the College Football Hall of Fame (1951). He made the Naismith Hall of Fame (1959) primarily for developing basketball as a five-player sport.

From Stagg, Conibear came to understand the importance of how things worked, how to break down the components of a situation, and how to reassemble them into a better whole.

While working under Stagg, Conibear encountered Bill Speidel, a second-year Chicago medical student (and father of Underground Tour founder Bill Speidel Jr.), who had captained and quarterbacked the 1903 University of Washington football team, coached by James Knight, also the director of Washington’s fledgling rowing program.

Speidel grew so impressed with Conibear that he contacted UW athletic manager Lorin Grinstead and jawed him into offering Conibear the job of athletic trainer, then talked Conibear into moving to Seattle.

The UW assigned Conibear to act as the schools general athletic trainer and coach of its track and field team. Soon thereafter, Grinstead asked Conibear to take over the rowing program from Knight, but Conibear told Grinstead that he “didn’t know one end of a boat from another.” Conibears inexperience didnt faze Grinstead, who placed Conibear in charge of UW rowing in the spring of 1907.

Conibear immersed himself in all aspects of the sport. He read books about the traditional Oxford style of rowing, becoming especially interested in how an oar strikes the water and the physiology of the actual stroke. He eventually came to believe that the Oxford style, in which oarsmen put their maximum power at the end of a long layback stroke, was not only unsound, but uncomfortable. To better understand the mechanics, Conibear plowed into physics and experimented endlessly.

He borrowed a skeleton from the UW biology department, carted it to his home at 4129 Brooklyn Avenue and set it on a rowing seat he had at his disposal. Conibear slid a broom handle into the skeleton’s hands to replicate an oar and moved the skeleton through stroke after stroke, noting what happened anatomically, and the position of the bones at each stage. Next, Conibear turned a bicycle upside down and turned the wheel with the palm of his hand, visualizing the wheel as water and his palm as the oar blade. Conibear began to understand that unless the oar blade struck the water at a speed equal to or greater than the water’s speed, there would be a moment of unwanted “drag.”

Conibears experiments led him to develop a stroke with a shorter layback, a snap to the oar blade the instant it hit the water. Conibears breakthrough style, based on leg drive, came to be known, variously, as the Conibear Stroke, American Stroke and Washington Stroke.

In his book, A Short History of American Rowing, Yale professor Tom Mendenhall wrote, “Perhaps the most permanent, extensive adaptation of the English tradition (of rowing) to American conditions came through Hiram Conibear at the University of Washington. . . . Conibear’s genius was to discover and absorb the central elements of English Orthodox and then adapt them to American conditions and physiques, to develop an unique American style.”

Almost from the moment he signed on, Conibear obsessed over making Washington “the Cornell of the Pacific” (Cornell had dominated the annual Intercollegiate Rowing Association Regatta in Poughkeepsie, NY, for a number of years). To achieve that end, Conibear needed more than a new stroke. He needed board members of the Associated Students of the University of Washington (ASUW) to elevate rowing to the same stature that football enjoyed. He required more racing shells and better athletes. He sought a permanent training facility, and he wanted to coach — and train — on a full-time basis. Conibear also wanted more than the $3,600 annual salary he received, and squabbled frequently with upper campus over that issue, and many others.

UW administrators, for example, frowned on Conibears attempts to expand the womens rowing program, which he had launched in 1908, and his practice of courting downtown Seattle businessmen to provide financial support for his various ambitions. Before long, the extroverted Conibear had developed a reputation as a campus politician famous for offending those deemed higher in the schools pecking order.

Conibear clashed with Victor Place, the UWs Director of Physical Culture, and its football coach. Place routinely tossed Conibear out of football practice, believing Conibear wanted to poach his players and convert them into rowers. Place’s successor, the dour Gil Dobie, also had a tug-of-war with Conibear over the same issue.

It’s difficult to imagine two greater coaching legends working simultaneously at the same university. Hired a year after Conibear (1908), Dobie had begun what would become a 58-0-3 record and NCAA immortality that still resonates. Conibear would change Americas rowing landscape for the next 40 to 50 years. Reporting done in their day suggests that Dobie didnt care for Conibear, and had qualms about Conibear’s never-ending trumpet blowing on behalf of rowing. For his part, Conibear resented the fact that upper campus looked more favorably on Dobie’s football team than on his rowing program.

Conibears politicking paid off in 1910. A year earlier, Seattle hosted the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exhibition (June 1-Oct. 16), a fair meant to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush. The Exhibition, Seattles first Worlds Fair, took place on a forested site northeast of downtown Seattle that ultimately became the framework for the University of Washington campus.

Most structures built for the fair were meant to be temporary, and Conibear managed to take possession of the Coast Guard Station and lighthouse, turning it into the home of his new Varsity Boat Club, which Conibear established as a social organization for upperclassmen. The building sat on Portage Bay near the west end of where the Montlake Cut is today (the Cut was not finished until 1916).

Conibear won six Pacific Coast Rowing Championships during his UW tenure, but nothing he did, not even his invention of his namesake stroke, had a bigger impact on his career, or on the development of the sport at Washington (and in the United States) than a 1912 meeting he had with two brothers eking out a living as boat builders in Coal Harbor, Vancouver, BC.

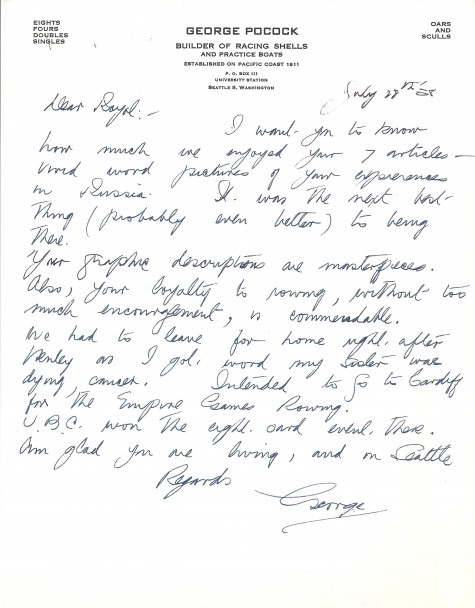

Accomplished rowers in their youth, George and Dick Pocock grew up in England, where they mastered the art of boat building from their father, who operated his own shop at Eton College. George began sculling at age 12, and won his first race at 15. In 1910, he captured the London Bridge-to-Chelsea race, a 4.5-mile event open only to professionals. Dick had won the race the year before.

Conibear awed the Pococks with his vision of transforming Washington into the “Cornell of the Pacific”, and ordered 12 new eight-oared racing shells. Although Conibear ultimately could only raise enough funds to pay for one shell, at a cost of $600, he convinced the Pococks to leave their boat-building business in Vancouver and set up shop on the Washington campus.

While Conibear re-invented the mechanics of the stroke, the Pococks changed the art of boat building through various innovations, including sliding seats, lightweight oars, special oarlocks, and a unique steering mechanism, replacing the tiller.

By 1913, Washington employed the worlds leading authority on how to most efficiently row a boat, and that man employed the designer of the worlds most technically advanced racing shells.

After a Conibear-Pocock eight-oared shell won the Pacific Coast Rowing Championship on April 19, 1913, on the Oakland Estuary, Conibear received an invitation to bring his rowing team to the IRA Regatta in Poughkeepsie to participate in a four-mile race against Pennsylvania, Columbia, Wisconsin and Cornell. Nobody expected much out of UW, especially since Stanford had been slaughtered at the IRA Regatta a year earlier, and West Coast rowing largely remained a secret.

Washington trailed early in the race, but recovered at the three-mile mark. UW shot past Pennsylvania, Columbia and Wisconsin in the final mile and threatened to win until Elmer Leader, one of two Leader brothers in the shell (also Ed) suffered an equipment problem. UW fell short by a length, trailing Syracuse and runner-up Cornell.

UWs third-place finish, especially among such elite company, rocked the American rowing establishment. East Coast schools, and their followers, suddenly recognized that Washington, and probably other West Coast programs (especially California), had become the real deal. Washington had not only been competitive, it had come within a length of winning. With this performance by UW, the complexion of American rowing had been irreversibly altered.

Conibear returned to Poughkeepsie in 1914, but UW didnt fare as well, finishing fifth. Conibear planned another trip east a year later, but by then, Henry Suzzallo ran the University of Washington (hired as school president on March 17, 1915). Suzzallo, a Stanford graduate and a Columbia educational sociology professor, had no room in his heart for intercollegiate athletics, or for the men who promoted them.

Suzzallo had dedicated his life to education, and believed that athletics had been wildly over-prioritized. He thought athletics should exist in a university environment strictly as an academic respite (letting off steam) and that the development of intercollegiate sports was anathema to the true purpose of a university. On a more basic level, Suzzallo resented the campus-wide popularity enjoyed by both Conibear and Dobie (Stan Pocock, George’s son and later a Washington rowing coach, confirmed as much in numerous interviews) and sought ways to dismiss both. But Suzzallo needed excuses that would wash.

Conibear provided him with ammunition by aggressively campaigning — Conibear had businessmen lined up to fund the trip — to take UW to Poughkeepsie for a third consecutive year, and by frequent public statements to the effect that the trip east had been assured. Behind the scenes, Suzzallo made sure it wasn’t, and likely fired Conibear. Later reporting revealed that Rusty Callow, ASUW President and an oarsman under Conibear in 1914-15, interceded, convincing Suzzallo to retain Conibear in exchange for Conibear taking a six-month leave (Stan Pocock also confirmed this) and henceforth staying out of campus politics.

In addition to Callows intervention, Conibear probably saved his job when he spoke to the ASUW board, saying, “I may be hard boiled. I may cuss. I may do considerable more talking on the campus than I should. But, I have put my heart and soul into this work, and, no matter what, I want to keep on. Don’t fire me. Let me keep on. We are on the road to something really worthwhile.”

If Suzzallo had little regard for Conibear, he had less for Dobie after Dobie publicly backed a player who had been accused of cheating on an exam. When the UW suspended the player, Bill Grimm, the remainder of the team went on strike, refusing to play a game against California. Suzzallo believed Dobie instigated the strike and fired him, saying, The chief function of a university is to train character, Mr. Dobie failed to perform his full share of this service. Therefore, we do not wish him to return. 58-0-3 and shown the door — without any evidence Dobie instigated anything.

After returning from a six month-sabbatical in the early spring of 1916, Conibear directed one of his greatest crews — it won the Pacific Coast Championship, beating Cal by 16 lengths on Lake Washington. The crew featured stroke Ward Kumm, Max Walske, who had been an All-American in 1913, and Paul McConihe, but it most notably included two future coaching legends: Ed Leader and Ky Ebright.

Leader, a member of Conibears 1913 eight-oared shell that finished third at Poughkeepsie, succeeded Conibear in 1919 (World War I derailed UW rowing in 1917-18), moved to Yale in 1922, becoming the first individual in an amazing Washington expansion that spread Conibear/Pocock conventions throughout the country. Leader stayed at Yale through 1942. His varsity Eli eight won the 1924 Olympic eight-oared gold medal in Paris.

Conibears coxswain, Ebright became an assistant rowing coach at UW and then head coach at California in 1924. He defined that schools program until 1959 (the Cal shellhouse is named after him). His eight-oared shells won Olympic gold medals in 1928 (Amsterdam), 1932 (Los Angeles) and 1948 (London), a year in which Ebrights Bears also denied Washington the right to represent the United States in the Olympics by beating the heavily favored Huskies (UW had two 1948 wins over Cal) at the Olympic Trials by two feet.

By the time of his retirement, Ebright had coached Cal crews to five of the schools 14 national titles, and defeated the Huskies eight times in UW-Cal dual meets, which dated to 1903, and won six IRA titles. Ebright went into the Rowing Hall of Fame in 1956.

Thus, Leader and Ebright, both Conibear disciples, won eight-oared gold medals in four of the five Olympiads between 1924 and 1948. The only year neither won was 1936, when Washington, under Al Ulbrickson, the varsity stroke under Callow, who had been coached by Conibear, won Olympic gold in London.

After Leader (UW, ’16) departed for Yale, Callow (UW, ’15), a graduate of Olympia High School, succeeded him. Callow returned the Huskies to Poughkeepsie in 1922, and they finished second. In 1923, Callow and UW won the IRA Regatta for the first time. Callow won again in 1924 and 1926 and had second-place showings in 1925 and 1927. Although UW had become a national power, it could no longer afford to retain him. Penn hired Callow in 1927 for $15,000 per year (he made $3,000 at UW) and he culminated a 37-year career at Navy, often labeled the Knute Rockne of rowing. Captain of Conibears 1915 crew, Callows Great Eight Navy team won the eight-oared race at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland.

Chuck Logg (UW, 22), who rowed under Ed Leader, became the rowing coach at Princeton, and made a national name for himself by snapping Yales five-year undefeated streak. He later coached at Rutgers.

Mike Murphy (UW, ’22), twice a captain and stroke under Leader, is generally credited with suggesting Huskies at the schools W Club meeting in 1922, as the school nickname (adopted). After graduating from Washington, he directed Wisconsins rowing program from 1928 through 1932.

Al Ulbrickson, who stroked Callows winning IRA crews in 1924 and 1926, became Washington’s head coach after Callow left for Penn. Ulbrickson coached UW through 1958.

Rollin Harrison “Stork” Sanford (UW, ’26), also coached by Callow, spent 34 years at Cornell, winning four consecutive national championships in the 1950s, six IRA titles and four Eastern Sprints.

Norm Sonju (UW, ’27), who rowed under Ulbrickson, spent 10 years as an assistant at Sanford and Cornell before becoming Wisconsin’s head coach, a position he held for 22 years. Tom Bolles (UW, ’26) started his coaching career as a Husky assistant and later directed Harvard’s fortunes from 1937 through 1951. He wound up in the Rowing Hall of Fame. Walter “Bud” Raney (UW, ’35), coached at Columbia, Delos Schoch (UW, ’37) at Princeton and Gus Eriksen (UW, ’38) at Syracuse.

Fil Leanderson, another disciple of Ulbrickson, succeeded his mentor in 1959, coached the Huskies through 1968 and led Western Washingtons program from 1977 to 1993.

MIT hired three different Huskies to head its crew program: Bob Moch (UW, ’36) from 1939-44, Jim McMillen (UW, ’37) and Bruce Beall (UW, ’73), who also coached at California. John Bisset (UW, ’58) and Jerry Johnsen (UW, ’64) both headed the UCLA program, Lou Gellermann (UW, ’58) served as head coach at Navy, and Kjell Oswald (UW, ’96) went to Oregon State.

By 1937, every elite rowing program in the country, save Columbia, Navy, and Syracuse, employed a head coach who had been taught by Conibear, Callow or Ulbrickson. Every college program used the Conibear Stroke, and virtually every school relied on Pocock-designed shells. Rowing had become Washingtons greatest athletic export.

Due in part due to his length of service (1927-58), Ulbrickson collected more hardware than any other UW head coach. His crews won six IRA titles, finished second five times and third eight times. His eight-oared shell won the 1936 Olympic gold medal, a 1948 four-oared boat also won gold, and his 1952 four-oared crew took a bronze.

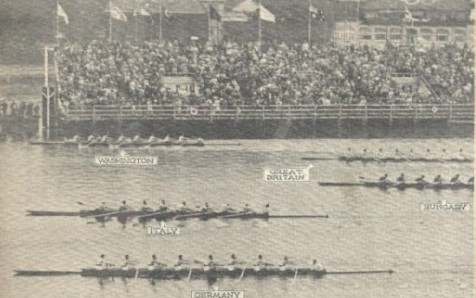

Given Conibears obsession with turning Washington into the Cornell of the Pacific, he would have appreciated (and found it ironic) the developments of June 22, 1946. The largest crowd ever to witness a sports event in the Pacific Northwest — 150,000 blanked out the Madrona Park shoreline, or watched from course-side yachts, cruisers, outboards, canoes and rowboats, as five premier crews from the east and Midwest — Cornell, Harvard, MIT, Rutgers and Wisconsin — came to Seattle to face off against Washington and California in the Lake Washington International Regatta.

It marked the first time eastern-based (or Midwest) crews had raced in the west. Five of the crews — Cornell (Stork Sanders), Harvard (Tom Bolle), MIT (Jim McMillin), Rutgers (Chuck Logg) and California (Ky Ebright) — had Washington alumni at the helm. All used the Conibear stroke, and all raced Pocock shells (Cornell won followed by MIT and Washington).

Ulbricksons ultimate triumph occurred in 1958 when his eight defeated Trud Club of Leningrad in Moscow, one of the greatest upsets in rowing history. Two individuals in that shell, Dick Erickson and Lou Gellermann, became head coaches, Erickson at Washington from 1968-77, Gellerman at Navy from 1964-68 (after leaving Navy, Gellerman returned to Washington and became freshman rowing coach under Erickson).

In 20 seasons at UW, Erickson led the Huskies to 15 Pacific Coast Rowing Championships, the 1970 IRA Championship and a national championship in 1984 at Cincinnati. Ericksons most significant win: in 1977 he became the first UW coach to win the Grand Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta.

Bob Ernst, hired by Erickson, became the first to coach mens and womens NCAA champions and also win an Olympic gold medal (1984 Los Angeles).

Conibear had been correct when, in 1916, he told the ASUW board threatening to oust him that we are on the road to something great here.

Since his time, more than 14,000 men and women have struck an oar in the water on behalf of Washington. UW men and women have combined to win 21 national championships and 172 conference titles (all categories of races). Eighty UW rowers have participated in 13 Olympic Games, and three Washington shells (1936, 1948 and 1952), all built by Pocock, have won Olympic medals.

Husky men and women have won races and regattas on such far-flung waters as the Thames in London, the Nile in Egypt, on reservoirs in Russia and Germany, and in gulfs off Finland. The National Rowing Hall of Fame includes 27 individuals who coached or rowed for Washington, and a dozen others who became Hall of Famers as the result of their work at other colleges after leaving Washington.

So the May 7 Windemere Cup is not so much a crew race as it is an extension of a fascinating history and tradition that now counts 110 years, another mark on a timeline that began when the UW was housed in three small buildings, when the Montlake Cut remained an idea, when William Goodwins rugby matches still served as local athletic entertainment.

Conibear did not live to see any of his dynamic legacy, or Pococks, play out. On the morning (6:45 a.m.) of Sept. 9, 1917, one year after Conibear begged to keep his job, a child named Marie Cornwall, who lived in the rear of the Conibear residence at 4129 Brooklyn Avenue, saw the coach scale a plum tree and shimmy out on a limb to pluck fruit. According to Cornwall, the only witness, Conibear stepped near the end of a branch, and it snapped. Conibear plunged headfirst to the ground. Mrs. Grace Conibear, who had been preparing breakfast in the kitchen, rushed outside and, assessing the situation, summoned Dr. Charles Davis, who lived a half a block away. The famous crew coach died shortly after the doctor arrived on the scene.

Cause: broken neck. Conibear was 46 years old.

————————————

DavidsWayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at the following e-mail address: seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

(Wayback Machine is published every Tuesday as part of Sportspress Northwests package of home-page features collectively titled, The Rotation.)

Note To Readers: If you have an historical topic you would like explored in the Wayback Machine, please leave your idea in the Comments section that accompanies this article.

16 Comments

Keep it up. The Wayback Machine is great! Loved the Conibear piece, and have really enjoyed others, like the Helene Madison one.

You write a good stick, sir.

I knew nothing of rowing, especially UW rowing but Dave made it interesting, thanks for another informative article.

All hail Steve Rudman, Nelson. His exhaustive research and engaging writing produced this terrific Conibear/Crew “Wayback”. Glad you liked it!

Dear David – Beautifully presented, fascinating story and so well written! I thoroughly enjoyed this history that every true-purple Husky can be proud of.

I’ve been working on an angle as to just why Gilmour Dobie has never received his proper due by the university. I would like to send you some hard facts to back up my position as to illustrate why the school and its fans never benefited from the great traditions built out of Dobie’s incomparable record of 1908-16. UW never took advantage of their Gil Dobie asset such as Stanford did with Glenn “Pop” Warner or Notre Dame did with Knute Rockne – and we all know there are many other legendary coaches who were lionized by their schools. The goodwill that derives from Washington’s rich traditions has been lost, but I don’t think this is forever. It can be regained and I think there is documented evidence that we can present to make the case.

Lynn Borland

Was Lou Gellerman, mentioned in this article, also the longtime Husky Stadium game announcer?

Quite fascinating. Thanks for the research and the reporting.

Millwood must really want out of Seattle because he’s making himself some attractive trade bait. I’m sure Jack Z. has some prospects in mind for him.

Definitely helping his trade value. Too bad same can’t be said of Chone Figgins.

I guess I can’t see sending Wells down but keeping Figgins around. If Figgy’s not going to be used, it’s past time to take a deep breath, cut him loose if we can’t trade him and eat his salary. Touting your commitment to youth while simultaneously jacking around one of your young players to accomodate a thirtysomething underachiever doesn’t engender credibility for your organization.

The club needs to start working on Figgins accepting his new role. Maybe have him speak with Mark McLemore on adjusting to an everyday bench role instead of starting. If they never use Figgins it doesn’t make sense to send Wells down though I do get why they did. But from a what’s good for the team standpoint sending Wells down is just wrong.

Pete O’Brien……

You are right about Pete O’Brien, who hated to hit in clutch situations. We confined this piece to the period 2000-present. Thanks for reading!

anyone remember Jeff Burroughs? but yeah, for more recent free agent screwups, it’s a tough call between Figgins and Silva, but I took Silva, because he was overweight (my brother called him Saliva), and because of the one-half of a good year he posted with the Cubs, which was annoying, and also because, it’s more fun to blame Bavasi than Zduriencik. ps what a great photo of Figgins . . .

God, I do remember Jeff Burroughs, although I don’t want to. Bavasi has to be the worst front-office hire in Mariner history. And thanks for your imput.