By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Any catalog of baseballs professional eccentrics inevitably starts with outfielder Jackie Brandt, owing to the fact that Brandt was the first player to whom the word flake was applied. It came courtesy of Brandts St. Louis Cardinals teammate, Wally Moon, during Brandts rookie year (1956), Moon observing, Brandt is so wild his brains sometimes fall out of his head, flaking off his body. Brandt lugged around the nickname Flaky for the remainder of his career (1956-67).

The Dickson Baseball Dictionary defines a flake as an odd or eccentric player; a kidder or comic; a kook.” As for flaky, the dictionary defines it as strange, eccentric, a bit off; a player who behaves oddly. Flakes mainly flourished before baseball went corporate after the arrival of free agency (1972), the mass extinction event for all but a few stragglers of Brandt’s flaky ilk.

Brandt played 27 holes of golf in 101-degree temperatures on the morning of a scheduled day-night doubleheader. With snow globe-brained clarity, he told reporters during spring training one year that he intended to play with harder nonchalance. Although Brandt had enough quirks to fill a psychiatric tome, he may not have been the reigning flake of the World War II era, despite the historical branding by Wally Moon.

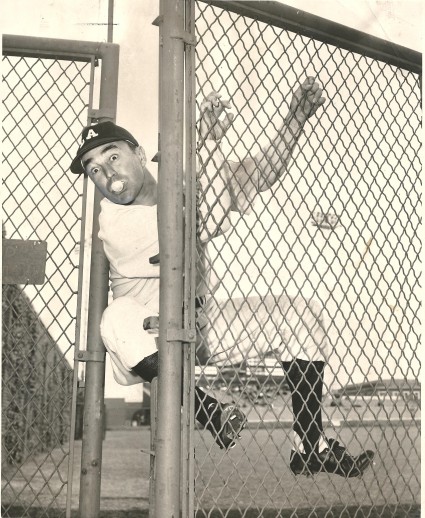

Jackie Price (1935-46), who spent part of his career in the Pacific Coast League, occasionally shot umpires with water pistols. He also gave pre-game demonstrations in which he took batting practice while suspended upside down from the hitting cage. Price reportedly could throw three baseballs with one hand and have each land in a different catchers mitt in the strike zone.

Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck hired Price in 1946 to serve as a pre-game entertainer and, as part of his act, Price wrapped boa constrictors around himself while playing catch or batting. Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau got rid of Price early in the 1947 season after Price let loose two of the snakes on a train to observe the reaction of a team of lady bowlers en route to a tournament.

Dick Tidrow (1972-84), John Lowenstein (1970-85), Jay Johnstone (1966-85) and Tug McGraw (1965-85) commonly top most lists of modern-era flakes. Tidrow specialized in sophisticated water pranks, and frequently used the bullpen phone to order Chinese takeout. McGraw grew prize-winning tomatoes in the Shea Stadium bullpen, and once took himself to jail and demanded to be locked up after blowing both ends of a doubleheader.

Mark The Bird Fidrych, named after the Sesame Street character, became a national sporting celebrity in 1976, not as much for winning 19 games as a rookie with the Detroit Tigers, but for his daffy routine of talking to the baseball, chattering to himself, kissing and cleaning the pitching rubber, aiming the ball like a dart, strutting around the mound after every out, and discarding baseballs that had hits in them.

No one who observed Fidrychs antics had seen anything like it unless they were old enough to have witnessed Chesty Chet Johnson pitch in the old Pacific Coast League in the late 1950s. Johnson was Fidrych and a lot more long before Fidrych emerged.

In fact, if Johnson had spent any significant time in the major leagues, he might be universally recognized today as one of the greatest flakes in the Dickson Baseball Dictionary sense — of all time instead of a largely forgotten curiosity. But Johnson spent only five games of his 625-game professional career (1939-56) in the majors after graduating from Ballard High School, just ahead of his brother, Earl.

Baseball has featured numerous brother acts the Alomars, Alous, DiMaggios, Boyers, Perrys, etc. — but none quite as intriguing as Chet and Earl Johnson, the second set of sibs from the state of Washington to reach the majors, following Chehalis natives Vean (1911-25) and Dave Gregg (1913).

While Chet became an eccentric fabulous enough that the Marx Brothers mainly Groucho, Harpo and Chico rarely missed his act, Earl became a World War II hero, decorated on a par with major leaguers Bob Feller (five campaign ribbons, eight battle stars), Warren Spahn (Purple Heart, Bronze Star) and Ted Williams (Air Medal with 2 Gold Stars, World War II Victory Medal).

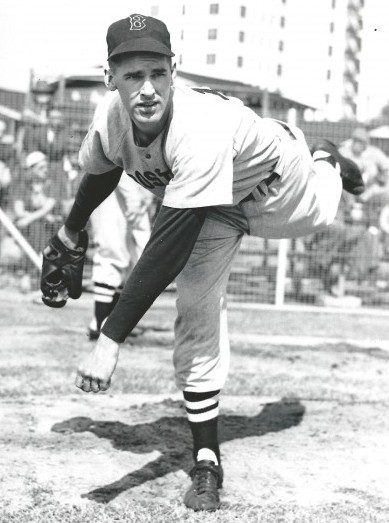

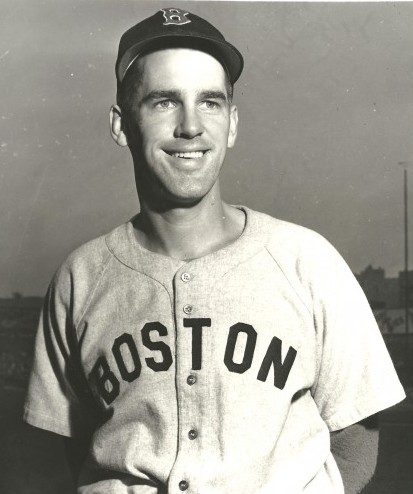

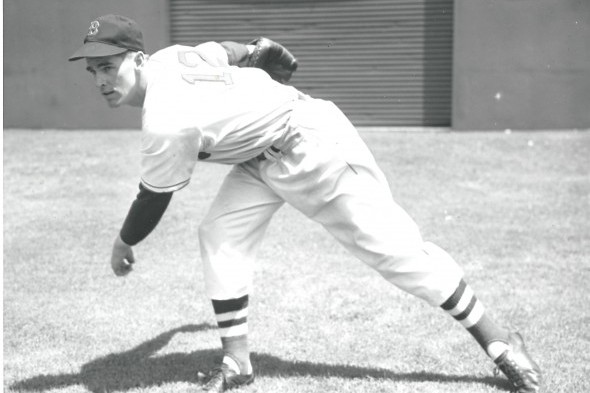

After graduating from Ballard High, Earl accepted a scholarship to play baseball at St. Marys College (Moraga, CA.). He reached the major leagues at age 21 with the Boston Red Sox, making his debut on July 20, 1940, in relief of future Hall of Famer Lefty Grove. Over the next two seasons (1940-41), Earl made 22 starts, going 10-7, and seemed to be developing into a fixture in the Boston rotation. But Uncle Sam inducted Earl into the Army less than a month after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (Dec. 7, 1941).

Assigned to the 120th Infantry (30th Division), Johnson spent his first year of service stateside (Camp Roberts, CA.) before the Army deployed him to Europe 21 days after D-Day (June 6, 1944).

We were a replacement unit, Johnson told the Providence Journals Bill Parrillo in an interview after the war. We had to go through Omaha Beach to get there. The wreckage was still there, the burned-out tanks and half-sunken ships and assault boats that were just so much twisted steel.”

Johnson told Parrillo that he served as a rifle platoon sergeant, involved in liberating towns in France and Belgium, and that on several occasions he came across scores of dead bodies, from both the Allied and Axis sides. He also witnessed the immediate aftermath of the Malmedy Massacre in Belgium (Dec. 17, 1944), in which Nazis murdered up to 150 American prisoners of war.

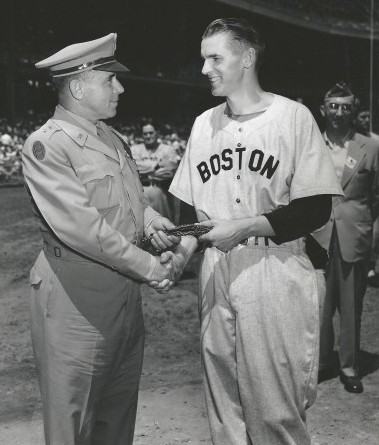

Johnson participated in five major conflicts, including the Battle of the Bulge. For his heroism, he received the Bronze Star, a Bronze Star with clusters, and the Silver Star.

Johnson earned the Bronze Star for his actions on Sept. 30, 1944, when he and his unit braved enemy fire and rescued a truck, thereby keeping it out of German clutches, that contained vital radio equipment.

He received the Bronze Star with clusters after he urged a tank crew to drive through a minefield en route to wiping out a German unit that pinned down his men.

He collected the Silver Star after he and another U.S. soldier encountered a German tank with its hatch open. Johnson lobbed a pair of grenades at the tank, but missed twice. The other soldier threw one grenade and scored a direct hit, killing five enemy soldiers.

During his Providence Journal interview, Johnson added, Im proud that I served my country, but prouder still to have made it home alive. What General Patton said is true: war isnt about dying for your country; its about making the other poor, dumb bastard die for his country. I was one of the lucky dumb bastards who made it home safely.

Earls fastball didnt return with him, forcing him to cultivate new pitches in order to remain in the majors. Relegated to the Boston bullpen in 1946, he appeared in just 29 games, but won Game 1 of the World Series against St. Louis by tossing two innings of scoreless relief (among his outs: fanned Marty Marion, got Stan Musial on a groundout and Enos Slaughter on a fly ball). After adding a slow curve, a changeup and a slider to his repertoire, Earl enjoyed his best major league season in 1947, when he won 12 games and posted a 2.97 ERA in 17 starts.

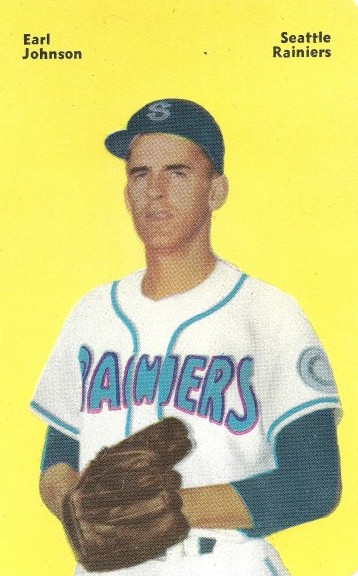

Johnson, a teammate of Red Sox legends Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr and Johnny Pesky, had one more decent year, going 10-4 in 1948, but had a hard time recording outs in 1949 (7.48 ERA) and 1950 (7.24). He finished his MLB career with the Detroit Tigers in 1951 (0-0, 6.35), and signed with the Seattle Rainiers on June 17, 1951 (he received the first ejection of his pro career in his first game with the Rainiers on June 26, 1951, for arguing balls and strikes with home plate umpire Lou Barbour) and went 8-5 through 1952, when he retired.

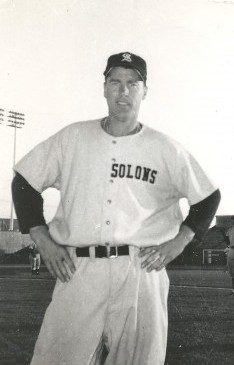

Chet, meanwhile, had just embarked upon a five-year run with the Sacramento Solons, and was in full flower as a flake.

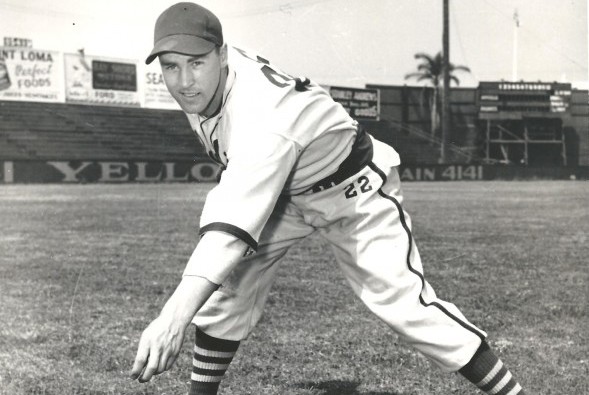

Chet never had Earls talent. He attended the University of Washington from 1937-39, but lettered in baseball just once (1939). Signed by scout Red Killefer, who managed the Seattle Indians from 1923-27, Chet bounced from one minor league club to the other over the next seven years, making stops at El Paso (D League), Hollywood (AA), Tacoma (B), San Diego (AA), San Francisco (AA), and Seattle (AAA) before he reached the majors at age 29 in 1946. On Sept. 12 that year, Chet became the fourth Husky to hit the show, following Royal “Hunky” Shaw (1908, Pirates), Tracy Baker (1911, Red Sox), and Dode Brinker (1912, Phillies).

Chets 1945 season with the Rainiers became the catalyst for his major league cup of coffee. He intended to retire and join the war effort, so he took a job at a Seattle-area defense plant. Figuring they could use another arm, the Rainiers worked out a deal with the PCLs San Diego Padres (Chets 1944 club) that allowed Chet to pitch for Seattle by scheduling his starts around his defense-plant shifts.

Chet made 27 appearances (25 starts) and went 14-12 with a 3.44 ERA. He threw 14 complete games, including five shutouts, by far his best year as a professional.

Always desperate for pitching, the woebegone St. Louis Browns purchased Johnsons contract from the Rainiers, but his minor league success failed to translate at the major league level. Johnson lasted just 18.0 innings spread over five games with a 5.00 ERA. (Later, when Johnson was asked if hed ever played major league baseball, he quipped, No. But I did pitch for the St. Louis Browns.)

According to an interview provided to SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) by Earl Johnson, Chets experience with the Browns changed his thinking about the direction of his career. When it became clear to him that he just didnt have the stuff to really succeed as a major league ballplayer, he began working up some routines designed to make people laugh and extend his baseball career.

“No doubt, that’s when Chet decided once and for all that his best shot at sticking around was to make a name for himself,” Earl told SABR. “The PCL was a good place for him. Not only was it home, but it was a more relaxed atmosphere. Most of the players had already had a shot at the majors and were on the downside of their careers.

“The truth was, a lot of the players would just as soon play out here on the Coast than with a fringe major league team like, for example, the Browns. The word we use now days is laid-back. That’s a good way to describe the old Coast League. Other guys might be better, but Chet was going to be different.

It did seem like Chet’s baseball career was always being overshadowed by other guys. In high school, it was (Fred) Hutchinson and then myself, Earl added.

Later on in Chet’s pro career, he was never what you’d call a star. And it seemed like folks always identified him as my brother. I think it bothered him after a point, and probably contributed to the way he eventually played the game.

Long before Moon designated Brandt baseballs first flake, Rube Waddell (1897-10) chased fire engines and wrestled alligators (most baseball researchers believe Waddell was retarded). Rabbit Maranville (1912-35) once faked the murder of an umpire during a game, replete with a gunshot.

Flakes come in a variety of guises, including the mentally unhinged (Waddell), pranksters (Sparky Lyle liked to plant his naked bottom on buffet spreads and birthday cakes), oddballs (Joe Charboneau opened a bank account wearing only his underwear), goofballs (Steve McCatty became a master of hotfoots), the superstitious (Ross Grimsley refused to shower during winning streaks and wore turquoise contact lenses) and ordinary head cases (Doug Rader ordered breakfast in hotel coffee shops with shaving cream on his face), and the delightfully zany, notably Tug McGraw.

McGraw, who once pitched an inning of spring training on St. Patricks Day wearing only bright, green long johns, had this reply when asked what he intended to do with a pay raise:

“Ninety percent I’ll spend on good times, women and Irish whiskey, McGraw replied. The other 10 percent I’ll probably waste.

Asked what losing meant to him, McGraw said, Ten million years from now, when then sun burns out and the Earth is just a frozen iceball hurtling through space, nobody’s going to care whether or not I got this guy out.”

The PCL featured a number of flakes before and during Chet Johnsons time, including the aforementioned Jackie Price. Also, Seattle-born (1890) Carl Sawyer, who played for the Los Angeles Angels (1913-14) and Vernon (CA.) Tigers (1921-23), liked to dance with a dummy during the seventh-inning stretch.

Broadway Bill Schuster, who had two stints with the Rainiers (1940-41, 1949-50), once belted a home run in Los Angeles. After crossing the plate, he planted a kiss on a blonde woman sitting in the stands. Another time, after making an easy-out grounder to the first baseman, Schuster veered off course, ran to the pitchers mound and slid in.

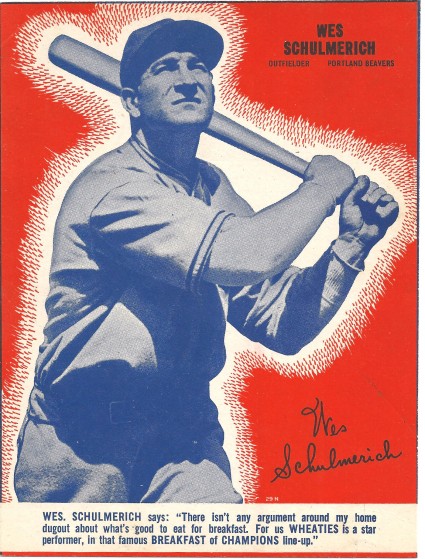

Wes Schulmerich, the first Oregon State player to reach the majors (1931 Boston Braves), played the outfield in the PCL and Western International League from 1927-39. He started off as a serious ballplayer, but eventually evolved into a baseball clown. I made a damn fool of myself, thats about what it amounted to, Schulmerich said. Playing for Portland (PCL) in 1937, Schulmerich had a ball bounce off his glove, costing Portland a game. When the crowd hooted him, Schulmerich laughed back at the fans. The Beavers released him immediately.

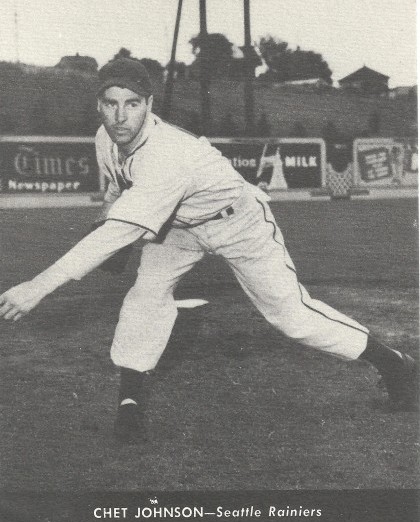

Chet Johnson pioneered dozens of routines, gimmicks and shticks, all well thought out and thoroughly practiced.

I loved to see the fans have a good time, Johnson said in an interview with SABR. My purpose was to make the hitters laugh with me or get so mad that theyd lose their concentration and swing at anything I threw.

Predating Fidrych by more than two decades, Johnson developed a one-way conversation with the baseball, jabbered to himself and bowed to the pitching rubber. He made a big show out of his warm-up tosses. As he dispatched them to the plate, each one slower than the preceding one, his catcher would fire them back, harder and harder.

The end of the routine came after Johnson had tossed his slowest pitch and received his hardest return throw. When the ball smacked Chets glove, Johnson would yelp in pain and remove the glove to reveal an oversized fake thumb, wrapped in a bloody bandage.

Johnson developed double and triple windups that drove hitters, opposing managers and umpires daft. He threw hesitation and blooper pitches, and sometimes fired the ball to the plate underhanded, like a softball pitcher.

Bob Hunter of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner wrote a column for the newspaper during Chets heyday: “For one thing, Johnson’s uniform never fit,” Hunter recalled. “It just hung on him.

“So that was funny. Then he would wear these ridiculous outfits. One time it was a coonskin cap, this at a time when the TV show Davy Crockett was popular. Another time it was a thick set of eyeglasses, which he wound up offering to the umpire.

“One time in Hollywood, he took the mound wearing a fake mustache like Groucho Marx used to wear. He might bring a umbrella up to home plate instead of a bat on a rainy day, or on a foggy day go up there wearing one of those miner’s helmets with the light on top.

“Oh my God, he would go through the strangest stuff out there on the mound,” veteran PCL pitcher Bud Watkins told minorleaguebaseball.com. “He might pretend to not be able to see the catcher’s sign. So he would creep in closer and closer and squint and shake his head until he finally was right in front of home plate, which is pretty funny in and of itself.

“Then he would get down on all fours and stare at the catcher’s crotch for a couple seconds, then stand up and shout ‘Eureka! I got it!’ and run back to the mound. OK, very funny, right? But Chet’s topper was the classic. He would then take his position on the rubber and, very seriously and deliberately, shake off the sign. If you weren’t laughing by then, you weren’t human.”

Bob Stevens of the San Francisco Chronicle watched Chet many times while he pitched for the Sacramento Solons. Stevens, who called Johnson a finished product of somebodys school of histrionics,wrote: He goes through routines that would put shame to Babe Ruth on the hangoverest day he ever had.

Stevens described Johnsons pre at-bat routine: Chet smoothes the spike-disturbed loam around home plate. With hands clutching the bat at opposite ends, he dramatically raises it above his head and flexes his muscles, all the while leering menacingly out to the pitcher, who must combat this ferocious-looking individual. Johnson swings the bat furiously back and forth over the plate, hunchbacked, ready, vigilant, defiant. Ordinarily, hes out of there after a maximum of three pitches, all of which he swings at mightily with great crashes of air but no sound of lumber against baseball.

Some of Chets stunts came right out of the Max Patkin school of jesting. Patkin, a rail-thin, rubbery-faced clown, spent 51 years knocking around minor league parks spoofing players, managers and umpires.

Chet carried a red handkerchief, about the size of a dishrag, in his back pocket. Striking a bullfighters pose from the rubber, Chet waved it as the batter stepped to the plate. If a batter hit a home run, Chet followed him around the bases, fanning him with the rag.

Chet also kept a small black notebook, which supposedly contained detailed information about the hitters he would face. As a hitter stepped to the plate, Chet would open the notebook and study it. If the batter got a hit, Chet would make a show of crossing out the “erroneous” information. If the batter homered, Chet would dramatically tear out the page, rip it up and toss the shreds to the wind.

“He used to buy those things by the box,” Earl Johnson said. “He would go through them pretty quick, but he never really had anything written down in ’em. It was just another thing to do to keep the hitters thinking.”

“It wasn’t easy working one of Chet’s games,” Cece Carlucci, a PCL umpire of that era, told SABR. “You had to watch the guy like a hawk because you never knew what the hell he was going to try to pull. But, God yes, he could be funny. The first time I saw that sore thumb bit, I just couldn’t stop laughing. I went out and told him. ‘Chet, don’t ever do that to me again. I gotta work here and you’re making it impossible.’ He was a good guy but just a little screwy, you know?”

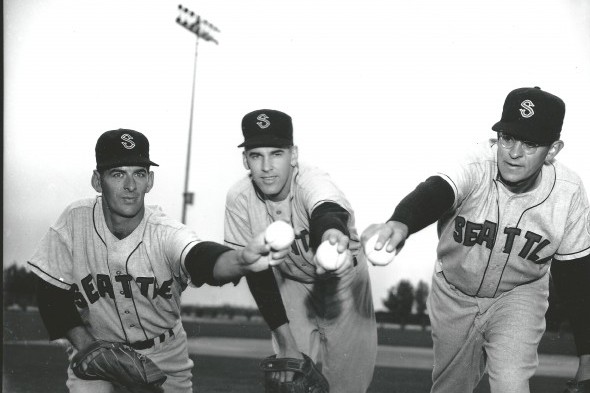

Brother Earl described for SABR an incident that occurred in 1951, when he played for the Rainiers, brother Chet for San Francisco, and Rogers Hornsby managed the Seattle club. Earl hated Hornsby, a sentiment shared by many players who labored under the famous Hall of Famer and notorious dugout tyrant.

Chet came into town with San Francisco and pitched against us, said Earl. Because he knew what I thought of Hornsby, he really put on a show. He did all the off-beat stuff, like double- and triple-pumping his arms on the windup, talking to the baseball, bowing to the umpire after a close call went his way, running off the mound after a strikeout, getting down on his hands and knees to dust off the pitching rubber, just Chet being Chet.

“Well, as this was going on Hornsby is getting hotter and hotter. He was muttering about what a disgrace to baseball Chet was and all that, and finally Chet struck out one of our guys and kind of did a mincing walk back to his dugout.

Johnsons antics became so polished that when he pitched at Gillmore Field in Hollywood, the Marx Brothers usually came out to see his work, and brought along friends, including Jack Benny, George Burns and Bing Crosby.

About the only thing he kept up on a wall of his home was a fan letter from Groucho Marx, in which Groucho complimented Chet on his routines, said Earl. That’s like Babe Ruth complimenting you on your hitting, don’t you think?”

Despite his focus on showmanship, Chet produced a couple of decent seasons after his cup of coffee with the St. Louis Browns. Pitching for Toledo and Indianapolis of the American Association in 1948, he went 16-12. In 1950, throwing for San Francisco of the PCL, he went 22-13 with a 3.51 ERA. He also won 12 games for Sacramento in 1953 and 10 for the Solons in 1955. He retired following the 1956 season after appearing in just 12 games. Overall, Chet had an 18-year professional career, compiled a record of 204-215, and was released seven times.

After his baseball career, Chet worked for Seattle Fuel, and then became a salesman for Cudahy Bar-S Meats until his retirement. He also refereed college basketball and football games, and worked with Earl as a pitching instructor at a summer baseball camp in Oliver, B.C. Chet died of cancer on April 10, 1983, two days after Bill Kennedy, a relief ace for the Rainiers from 1955-60, also died of cancer in Seattle.

War hero Earl Johnson ran a laundromat in Ballard for the many years. He suffered a stroke in 1990 and died in Seattle on Dec. 3, 1994.

David Eskenazis Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

———————————————–

Wayback Machine is published every Tuesday

————————————————

Note To Readers: If you have an historical topic you would like explored in the Wayback Machine, please leave your idea in the Comments section.

1 Comment

There’s a big place in my heart for baseball flakes! They give the game color, sometimes excitement. I spent an afternoon with Jimmy Piersall and saw odd behavior practiced with zest!!