By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

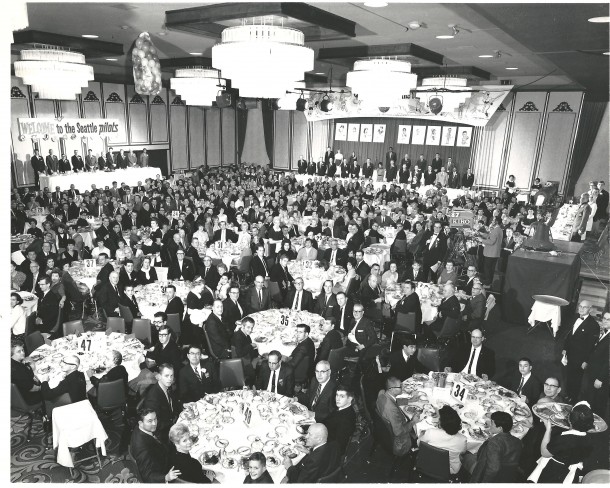

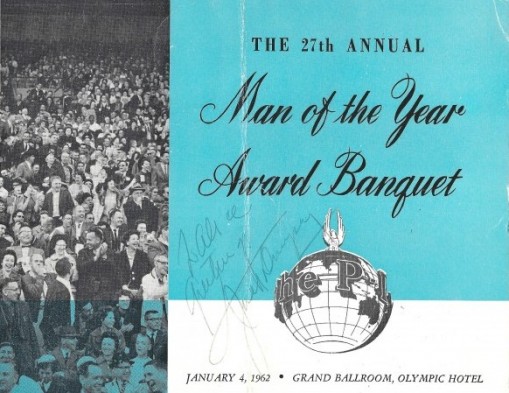

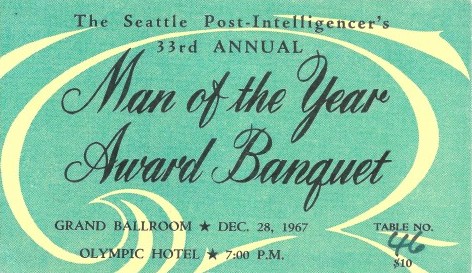

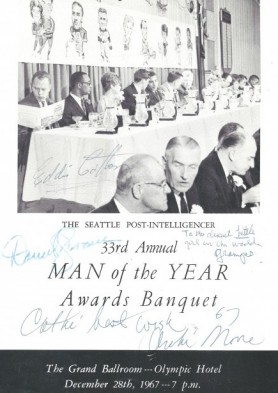

For the amusement of his audiences, Man of the Year sports awards program (78th edition of which is Jan. 25 at Benaroya Hall), founder Royal Brougham, lead sports columnist at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, enjoyed spicing his annual Olympic Hotel “clambake” with skits and vaudeville acts.

One year, Brougham attached a pair of dummy ducks to a wire that had been rigged across the ceiling of the Olympics Grand Ballroom. The plan called for Joshua Green, then an antique Puget Sound shipping icon, to raise a shotgun and wait until the ducks had been “released,” at which point Green would fire two blanks at them. But when Green raised the shotgun, the ducks somehow got jammed on the ceiling wire.

Green waited patiently for a few minutes, but then his arms grew heavy, and he slowly dropped the gun barrel to the point where it was aimed directly at guests, like a hand grenade with its pin pulled. Needing no instructions from master of ceremonies Jack Gordon, banquet goers dove en masse for cover.

It scared the holy hell out of half the people in the room, Gordon told the Post-Intelligencer. They (the audience) didn’t know if the gun was loaded or had blanks or what, and he (Green) looked like he had no control at all.

When the ducks finally were released, Green got off two shots without incident, still startling the crowd.

Another year, Brougham arranged to have an eight-foot replica of a Boeing jet fly across the room. But it turned out to be heavier than Brougham expected, and performed a series of swoops and touchdowns on tabletops, sending banquet attendees scurrying for shelter under dining tables.

Brougham’s banquet stunts always enlivened the Man of the Year awards, which, by the 1960s had become one of the most anticipated events on the Seattle sports calendar (KING TV broke into programming to televise the announcement of the winner).

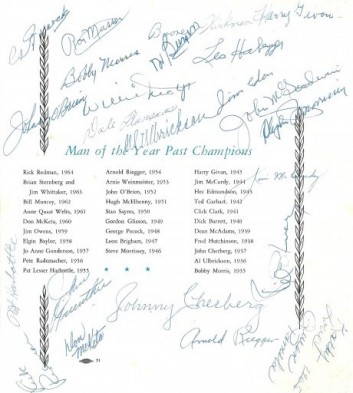

As it had in the previous three decades, football produced the most Man of the Year winners in the 1960s — three. Two more women — golfer Anne Quast Decker in 1961 and Olympic swimmer Kaye Hall in 1968 — also joined the ranks of female Man of the Year winners, matching the total from the 1950s. And, late in the decade, major professional sports began an inexorable takeover of the MOY program.

Had the decade’s first winner had his dream fulfilled, he never would have attended the University of Washington, never would have become the heart and soul of the Purple Gang, and never would have had a chance to become Man of the Year.

The 1960 winner grew up in a small coal-mining town in rural Pennsylvania, forced to quit high school because his family needed money.

So he went to work for a construction company at the age of 15. A year and a half later, he got a job climbing telephone polls on behalf of the Philadelphia Electric Co. Then he joined the military.

When he got out, he was 23 and, more than anything, wanted to play football for Len Casanova at Oregon. So he packed everything he owned into a Ford convertible and headed from Pennsylvania to Eugene.

When he arrived, he drove around for a while, thinking about how much he wanted to play for the Ducks. But when he discovered that Oregon had no interest in him, he drove on to Seattle, where his life would change.

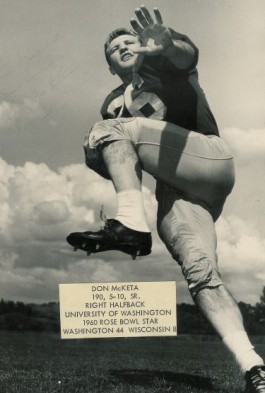

1960 / DON MCKETA, UW Football

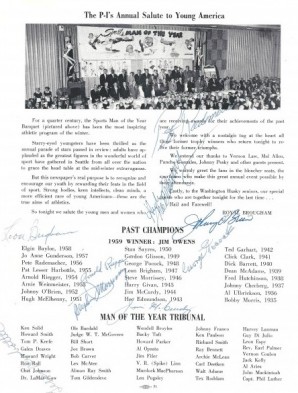

Not since 1937, when rowing coach Al Ulbrickson (see Wayback Machine: UW Bonanza At The 1936 Olympics) appeared on the ballot one year after claiming the Man of the Year award (1936), had a prior winner returned to the head table. But JoAnne Gunderson Carner, the 1957 winner, was back, along with tennis player Janet Hopps, also a 1955 finalist, who had reached the semifinals at Wimbledon in both doubles and mixed doubles.

But not even Carner, who in 1960 had won the second of what would become five U.S. Women’s Amateur titles, nor former Franklin High football-basketball-baseball star Ron Santo (see Wayback Machine: Ron Santo), a first-time nominee who just entered the major leagues with the Chicago Cubs, could derail the candidacy of University of Washington football star Don McKeta, who emerged as the toughest, most resilient and, by far, the most inspirational player on two of the greatest football teams in UW football history.

Still giddy over Washington’s unprecedented back-to-back Rose Bowl wins, which had not only elevated the schools national profile but that of West Coast football as a whole, Man of the Year voters at the Olympic Hotel went for McKeta in a big way, leaving Olympic boxing bronze medalist Quincy Daniels and Joe Budnick, who managed the Cheney Studs to a national semipro baseball championship, among others, wanting.

McKeta served as game captain for both the Huskies’ 44-8 romp over Wisconsin (1960) and their 17-7 win over Minnesota (1961). He had twice earned the Guy Flaherty medal, given annually to Washington’s most inspirational player.

In the 52-year history of that award, only Tom Wand in 1911-12 won it twice. In addition, McKeta was a first-team All-West Coast selection.

This is what made McKeta most inspirational: He helped Washington clinch its second Rose Bowl berth (1961) by catching a two-point conversion, despite a leg wound that required eight stitches to close, that gave UW an 8-7 victory over Washington State in the 1960 Apple Cup.

He probably was not the most gifted athlete, but ‘had a huge heart and was willing to sacrifice personal glory and recognition and made the team’s success his No. 1 priority,” Hugh McElhenny said of him (see Wayback Machines: Hugh McElhenny And The Kings and McElhenny’s 100-Yard Punt Return).

A 1963 MOY finalist and the 1964 winner, Rick Redman, best explained why McKeta was an easy choice as the 1960 winner.

“Don was the unsung hero and team leader who, more than any other player, set the example of total commitment and performance beyond talent that became the cornerstone of the Husky tradition.”

McKeta was nominated, with UW imput, over Bob Schloredt. It said more about McKeta than it did about Schloredt that Schloredt, a two-time Rose Bowl MVP, couldn’t even make the MOY ballot.

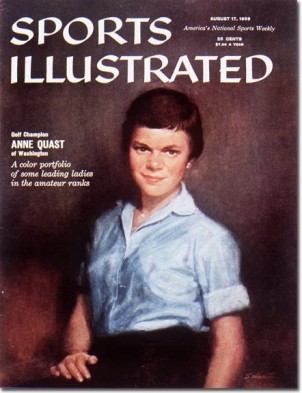

1961 / ANNE QUAST DECKER, Golf

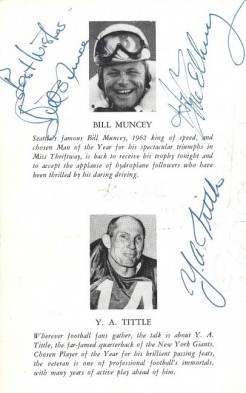

A Man of the Year finalist in 1958 playing under the name Anne Quast, Anne Quast Decker won the award in 1961, defeating a field that included a future inductee into the College Football Hall of Fame (UW’s Chuck Allen), a future member of the Motorsports Hall of Fame (hydroplaner Bill Muncey), and a future member of the Baseball Hall of Fame (Franklin High’s Ron Santo of the Chicago Cubs, back on the ballot for the second year in a row).

In all fairness to Allen, Muncey (on the ballot for the second time) and Santo, as well as future (1984) Olympic gold medalist Bill Buchan, the 1961 World Star Class sailing champion, nobody had a better 1961 portfolio than Quast Decker, whose major achievement was, in fact, historic.

Already famous in the Northwest, as well as nationally, for having become, on Aug. 17, 1959, the first state of Washington native to appear on the cover of Sports Illustrated, Quast Decker showed up at the Tacoma Country & Golf Club during the second week of August so intent on winning the U.S. Women’s Amateur on her home turf that she admitted to some embarrassment over it.

“It’s terrible to want something as badly as I want this, Quast Decker, a Stanford student, said. But this is my home. I’m here, with my husband, my friends, my mother and my father. They’re all here watching. I want so desperately to win.”

No problem. In fact, existing USGA records supplied no instance in which one woman so dominated the 61-year-old tournament. In her string of seven victories, Anne never trailed at any point.

She lost only six holes out of 112 played, finishing the week at nine-under par, scoring 19 birdies. Quast Decker ended the 36-hole championship round with a record-breaking 14 and 13 victory over Phyllis Preuss of Pompano Beach, FL.

Anne stood 6 up at the end of nine, 12 up at the end of 18, and by then it was just a matter of time and holes — the afternoon round became a mere formality, ending on the 23rd hole.

Her 14 and 13 win broke a 33-year-old record. The previous mark for a lopsided Women’s Amateur final dated to 1928, when Glenna Collett defeated Virginia Van Wie 13 and 12 at Hot Springs, VA.

“Frankly, it’s not a record I wanted to set,” Anne said. “I think I was pulling harder than anyone for some of her (Preuss) putts to drop late in the match.”

In addition to her U.S. Amateur wins (1958, 1961, 1963), Quast Decker finished as runner-up three times (1965, 1968, 1973). Another accomplishment: At the 1957 Titleholders Championship for amateurs and professionals, Anne came in second to LPGA Tour star and future Hall of Famer Patty Berg.

After her third U.S. Amateur win in 1963, Anne reappeared on the Man of the Year ballot, losing to UW pole vaulter Brian Sternberg and mountain climber Jim Whittaker.

She thus joined Al Ulbrickson (see Wayback Machine: Hiram Conibear’s Rowing Legacy), who appeared on the 1937 ballot after winning in 1936, and JoAnne Gunderson Carner, a finalist in 1960 after winning in 1957, as the third individual with that distinction.

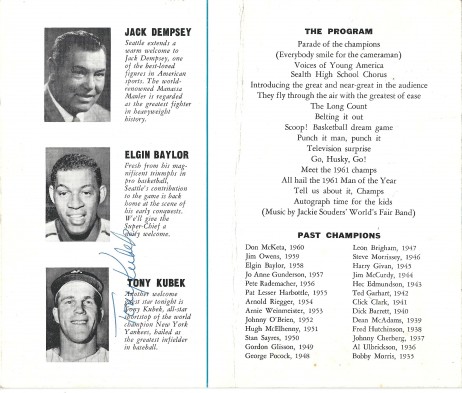

1962 / BILL MUNCEY, Hydroplanes

Nominated for Man of the Year in 1956 and again in 1961, Bill Muncey finally came out on top in 1962, prevailing over a slate that included Totems star Bill MacFarland (see Wayback Machine: Bill MacFarland & The Totems), boxer Eddie Cotton, a future winner, fastpitch whiz Bob Fesler (see Wayback Machine: Rainiers & Pitchers of Beer), and PBA bowler Darylee Cox, an amateur who had toppled one of the sport’s all-time greats, Harry Smith, in the finals of the Silver Lanes Open in Spokane.

MacFarland would have been an excellent selection as Man of the Year. He led the Totems and the Western Hockey League in scoring (46 goals, including three hat tricks) in 1961-62 and walked off with the league’s Most Valuable Player award.

Seattle golfer Kermit Zarley, appearing on the ballot for the third time, also would have made a good choice. Competing for the University of Houston, he won the NCAA Championship, the first such win by a Seattle native.

But Muncey, a third-time nominee, steered the Century 21 hydroplane, named for the Seattle World’s Fair, to victories in the Gold Cup, Governor’s Cup, President’s Cup, Diamond Cup and Detroit Regatta, a resume that swayed voters.

Muncey ultimately accumulated 62 victories, including eight Gold Cups and seven season driving championships. Muncey died in a crash in Acapulco, Mexico, Oct. 18, 1981, while on the lead in the World Championships.

1963 / BRIAN STERNBERG, Track & JIM WHITTAKER, Climber

Man of the Year voters did the only thing they reasonably could do in 1963: end the balloting in a tie, a first in Man of the Year history.

It simply became too hard to choose between a 19-year-old pole vaulter who set three world records in a two-month span, only to have his career end in a tragic trampoline accident, and the first American to summit Mount Everest.

If career achievement had meant anything to the tribunal that voted on the Man of Year award — a group that event founder Royal Brougham dubbed his Supreme Court — Golden Guyle Fielder (see Wayback Machine: Guyle Fielder & the Seattle Totems) probably would have won.

Fielder appeared on the ballot in 1955 and again in 1958, losing initially to the first woman named Man of the Year (Pat Lesser, see Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year: 1950-59), and buried under an Elgin Baylor avalanche his second time at the banquets head table (see Wayback Machines: The Two Lives of Elgin Baylor and A Bakery That Served Up Basketball).

By 1963, Fielder won five (of his six) WHL MVP awards and six (of his nine) league scoring titles. But Fielder, the greatest player in Seattle Totems history, couldn’t overcome the emotion generated by Sternberg and Whittaker.

He thus joined Jack Medica, Freddie Steele, Al Hostak, Bill Lawrence, Hal Turpin, Bob Houbregs, Johnny Guenther, Nancy Ramey and Bob Schloredt on a lengthening list of great local athletes never to claim the MOY.

The 1963 ballot included several worthy candidates, including fuel-additive entrepreneur Ole Bardahl, representing the APBA Gold Cup winning Miss Bardahl; Blanchet basketball coach Don Zech, who had led his team to a state title; Ted Nash, the outstanding oarsmen for the Lake Washington Rowing Club who had won a gold medal in coxless fours at the 1960 Summer Olympics, and Anne Quast Welts, winner of the U.S. Women’s Amateur for the third time, and the Man of the Year in 1961.

But Sternberg and Whittaker owned the MOY show.

On April 27, 1963, Sternberg established a world outdoor pole vault record of 16-5 in front of 37,432 fans at Franklin Field in Philadelphia during the Penn Relays.

On May 26, 1963, Sternberg broke that record with a leap of 16-7 at the Modesto (CA.) Relays in a meet in which UW teammate Phil Shinnick also set a world record in the long jump that was later disallowed.

Then, on June 7, 1963, Sternberg set another world outdoor mark, his third of the year, by clearing 16-8 at the Compton (CA.) Invitational.

A 1961 graduate of Shoreline High, Sternberg suffered his paralyzing injury July 2, 1963, when he attempted to perform a double-back somersault with a twist while working out on a trampoline at Hec Edmundson Pavilion on the UW campus in preparation for a trip to Russia.

Sternberg landed hard on his neck, and was left a quadriplegic.

At first, the prognosis for Sternberg was bleak. But he persevered and later became an annual attendee at Man of the Year banquets.

Just months after his training accident, on Jan. 27, 1964, the Helms Athletic Foundation named Sternberg as the outstanding amateur athlete for North America in 1963.

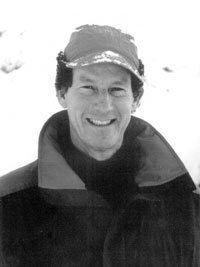

Although known best for a single feat reaching the summit of Mt. Everest May 1, 1963, Whittaker’s adventuring career eventually went considerably beyond his Everest ascent.

In 1978, he led the first American ascent of K2, the world’s second-highest peak.

In 1990, against formidable political and logistical odds, he organized the Mt. Everest Peace Climb, which placed 20 men and women from the U.S., China and Soviet Union on top of the world’s highest peak — during the Cold War, no less.

In addition to his mountaineering exploits, Whittaker became an accomplished scuba diver and blue-water sailor, twice skippering his own boats on the 2,400-mile Victoria to Maui race.

In a four-year span, Whittaker also sailed his 54-foot steel pilothouse ketch, “Impossible,” from his home in Port Townsend to Mexico, throughout the South Pacific to Australia and back, a journey of more than 20,000 miles.

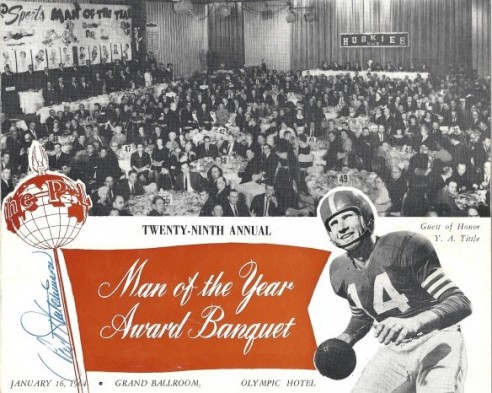

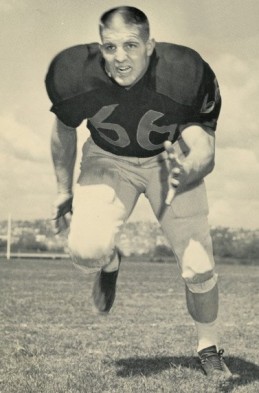

1964 / RICK REDMAN, UW Football

Continuing a trend from the 1950s, a representative of the hydroplane community appeared on the Man of the Year ballot in three of the first four years of the 1960s, Bill Muncey finally winning in 1962 in his third time in the finals.

In 1964, Royal Brougham’s Supreme Court came to the conclusion that it could no longer ignore Ron Musson, pilot of the Green Dragon Miss Bardahl, the best and most popular boat on the circuit.

During the 1964 season, Musson and Miss Bardahl won the Gold Cup at Detroit, the Dakota Cup at New Town, ND., the Seafair Trophy, and the Harrah’s Tahoe Trophy. Musson likewise took second place in the Diamond Cup at Coeur d’Alene, ID, the President’s Cup at Washington, D.C., and the San Diego Cup. For his overall performance, Musson won his first National High Point Driver Championship in the Unlimiteds.

But popular as Musson and the Miss Bardahl were, Man of the Year history suggested emphatically that it was virtually impossible for a Husky not to win in a Rose Bowl year, especially after UW had recovered from an 0-3 start to get there.

The Supremes placed two Huskies at the head table — running back Dave Kopay and linebacker Rick Redman, making his second consecutive appearance.

While Kopay had led UW in rushing yards in the 17-7 loss to Dick Butkus and Illinois in Pasadena, Redman became the sixth Husky football player named Man of the Year, following (see Wayback Machine: Man of the Year (1935-49) Dean McAdams (1939), Jim McCurdy (1944), Hugh McElhenny (1951), Arnie Weinmeister (1953) and Don McKeta (1960).

Redman, the 30th Man of the Year, played nine years in the American Football League, and in exactly 100 games for the San Diego Chargers after leaving UW. He made one Pro Bowl appearance, in 1967.

Redman’s win also closed the book on former Franklin star Ron Santo’s Man of the Year aspirations. Making his third appearance in the finals (also 1960 and 1961) after hitting .313 with 30 home runs for the Chicago Cubs, Santo never again reached the head table — not even after his best overall season, 1966, when he once again hit 30 home runs and led the National League with a .412 on-base percentage.

1965 / JOHN GOODWIN, Football Coach

Royal Brougham’s Supreme Court had a number of worthy achievements to mull over in 1965, ultimately deciding to return bowler Johnny Guenther to the ballot for the third time after he established two PBA world records en route to winning the Oxnard, CA. Open (rolled 2,022 for one eight-game block and came back with 1,808 for a 16-game total of 3,830).

The Supremes also brought back hydroplaner Ron Musson for a second, and what would prove to be the final time, after the future Motorsports Hall of Famer won the World Championship at Lake Tahoe in the Miss Bardahl.

Every every other Man of the Year candidate appeared on the ballot for the first time, including former ODea sprinter Charlie Greene of the University of Nebraska, who won the 100-yard race at the NCAA Championships, and Ingraham High’s Eric Klein, winner of the high (6-3 ½) and long jumps (24-2 ½) at the state track meet (also placed second in the 120-yard hurdles at 14.4).

Two other MOY candidates had not been on any sports watcher’s radar at the beginning of 1965. But Steve Krause, a 15-year-old trainee at the Cascade Swim Club, rocked the swimming establishment by simultaneously setting a world record and winning the 1,500-meter freestyle at the 1965 U.S. Long Course National Championships.

And the University of Washington’s Dale Flansaas, who would coach the USA National Women’s Team in the 1976 Montreal Olympic Games, led the Huskies to a surprise silver medal at the Women’s National Collegiate Gymnastics Championships by winning three of four individual events (vault, bars and floor exercise) and placing fourth in all-around.

But in a banquet shocker, the Supremes opted for a high school football coach, the first time they had selected such an individual.

John Goodwin hadn’t done anything in 1965 that he hadn’t been doing for years (he coached at Seattle Prep since 1948), and what he did was coach a lot of winning football teams. Twice in the previous two years, Goodwin’s Panthers had topped the state’s Associated Press prep poll. His 1963 team was unbeaten. MOY voters, it seems, sought to recognize a career rather a year.

When Goodwin, a 1940 graduate of Gonzaga Prep, resigned at Seattle Prep in 1967 to become an assistant at UW, his teams had won 114 games in 19 years, lost 44 and tied 13. During the 1960s, Goodwin coached two state championship clubs and put together a 21-game winning streak. When MOY voters acknowledged him, Goodwin’s Panthers teams lost just once in the previous four years.

The 1965 Man of the Year ballot was intriguing not so much for the fact that a high school coach won for the first time, but for what the final ballot lacked: the name of Dave Williams, tight end for the University of Washington football team. Williams made All-America, All-Coast and set receiving records — notably a school-record, 257-yard receiving performance against UCLA, and a school-record 10 touchdowns — that would stand for nearly 50 years.

We could go on and on about Williams. In fact, we did: see Wayback Machine: Dave Williams’ Amazing Legacy.

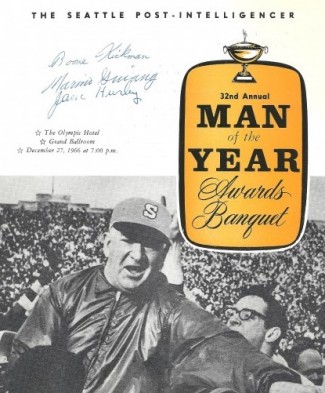

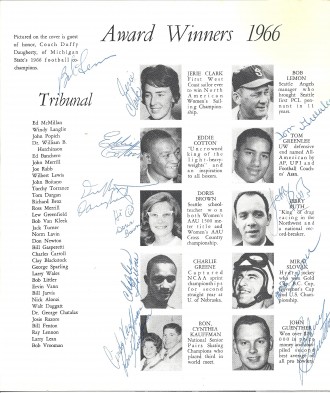

1966 / EDDIE COTTON, Boxing

Eddie Cotton is the only one of Royal Brougham’s Man of the Year recipients who won for losing — probably not once, but twice.

The first of the 83 professional matches Cotton fought that really mattered was Aug. 29, 1961 at Sicks’ Stadium (see Wayback Machine: A Fire That Changed Our Sports) when 4,000 fans showed up to watch Cotton try to wrest the National Boxing Association’s world light heavyweight title from Harold Johnson. The fight went the route, 15 rounds, and its controversial outcome irked the partisan assemblage. Judges scored it 145-147, 145-147, 148-144 in Johnson’s favor.

Cotton never got another title shot after that split decision until Aug. 16, 1966, when he entered the ring at the Las Vegas Convention Center with an opportunity to snatch both the WBC and WBA light heavyweight titles from defending champion Jose Torres. Oddsmakers didnt give Cotton much of a chance.

Like his first, Cotton’s second appearance in a championship bout also went 15 rounds. And, like the first, it ended with a controversial decision, Torres winning on all three cards, 70-67, 68-67, 69-68. Ring Magazine thought so much of the show that it voted it the Fight of the Year.

Man of the Year voters thought so much of Cotton’s performance that it bestowed on him Brougham’s annual prize while conferring second-banana status on an impressive slate of candidates.

Seattle Pacific’s brilliant long-distance runner, Doris Brown, had become the first women to run a sub-5 minute mile indoors, clocking 4:52. Jerie Clark, a 5-foot sailor, skippered her team to the Women’s North American Sailing Championship.

Former ODea High track star Charlie Greene, an NCAA sprint champion in 1965, was back on the ballot after claiming the 100 at both the National AAU and NCAA Championships.

Two other finalists re-emerged for new consideration. Seattle bowler and PBA star Johnny Guenther was back for a fourth time (also 1954, 1959 and 1965).

Unfortunately for Guenther, he would, due to Cotton’s appeal to voters, set a Man of the Year record for most times as a finalist (4) without winning.

Another previous finalist (also 1958-59), hydroplane driver Mira Slovak, had won the National Points Championship as well as the APBA Gold Cup

The most intriguing newcomers to the head table: pairs skaters Cynthia and Ronald Kauffman, winners of the 1966 U.S. Nationals. Oddly, the sister-brother tandem would go on to win three more U.S. pairs titles (1967-69), two North American titles (1967, 1969), score podium finishes at two World Championships (1967-68) and compete in the Olympics (1968, Grenoble, France), but would never again make the MOY final 12.

Cotton fought his last pro fight Aug. 2, 1967, flooring a tomato can named Ernie Gipson in one round in Anchorage, AK. He then worked for Boeing as a tool and die maker, served on the Washington State Boxing Commission, and operated a popular eatery on East Madison Street in Seattle which bore his name.

Cotton died June 24, 1990, at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle from an infection in his blood and lungs that developed two days after a second liver transplant, performed June 11.

1967 / HARVEY LANMAN, High Schools

Royal Brougham’s Supremes placed an eclectic cast up for consideration on the Man of the Years 1967 ballot, including an ice skater, a gymnast, a badminton player and a curler, and then proceeded to bestow banquet laurels on a high school administrator over U.S. ice dancing champions John Carrell and Lorna Dyer, UW defensive end Dean Halverson, hydroplane driver Billy The Kid Schumacher, and the best athlete on the board, Husky tight end Williams, twice a finalist, never a winner.

Lanman was director of athletics for Seattle and Metro League high schools for about a decade when tapped by the Supremes, in large part because he pioneered the use of artificial turf in Seattle (and the nation), first installing it in the mid-1960s at Memorial Stadium at the Seattle Center.

Before the rug went down, Lanman first had to convince the King County Medical Association that artificial turf was safe. Then he had to persuade high school coaches that artifical turf was superior to natural grass.

Finally, Lanman convinced the Seattle School Board that artificial turf was cost effective. He accomplished that by advising administrators that he could have the turf installed without school money. Lanman devised a way to finance the turf through proceeds from a nearby stadium parking lot.

Lanman came to Washington state armed with a business degree from Northwestern, intent on receiving an advanced degree at UW. After Lanman enrolled, he talked with athletic department officials, who offered him a job as a football assistant coach under Jimmy Phelan, a three-time MOY nominee, but never a winner.

Lanman departed UW after a year to become football and baseball coach at Franklin High.

During World War II, he served as an officer in the Navy pre-flight program (see Wayback Machine: Pest Welchs Crazy War Years) and later as a catapult and flight-deck officer on the USS Hancock and USS Shangri-la in the South Pacifric.

Lanman returned to Franklin after the war, and his 1952 Quaker football team won the Metro League title, as did his baseball teams in 1955, 1956 and 1957. As school district athletic director from 1961-71, Lanman was instrumental in expanding the athletic offerings to include cross country, wrestling, soccer and gymnastics for boys, and volleyball, golf, tennis and track for girls.

Most interesting about the 1967 ballot, at least in retrospect, is that the nominated gymnast, the UW’s Yoshi Hayasaki, won the 1968 National AAU all-around and back-to-back NCAA all-around titles in 1970-71, but was nominated just once more (1970) for Man of the Year.

1968 / KAYE HALL, Swimming

Tacoma’s Kaye Hall announced herself to the international swimming community in 1967 when, as a 16-year-old, she earned a silver medal in the 100-meter backstroke at the Pan American Games in Winnipeg, Manitoba. In case anyone missed her coming out, three months after the Pan Am Games, Hall became the first woman to break the one-minute barrier in the 100 back, putting her in the record book for a milestone achievement alongside Al Vande Weghe, the first man to do it in 1938.

A year later, the 17-year-old Hall not only whipped the woman who beat her in Winnipeg, Canada’s Elaine Tanner, she set world and Olympic records at Mexico City in the 100 back, won another gold in the 4×100 medley relay, and took a silver in the 200 back.

Given her Mexico City haul, best by a state swimmer in an Olympics since 1936, when Jack Medica won a gold and two silvers in Berlin (see Wayback Machine: UW Bonanza At The 1936 Olympics), Man of the Year voters made her their choice over a slate that included Bob Rule, the top scorer for the expansion Seattle SuperSonics; Pasco native Ray Washburn of the Cleveland Indians, who had tossed a no-hitter against the San Francisco Giants (Sept. 18); local golfer Don Bies, who had surprisingly tied for fifth place in the 1968 U.S. Open, and UW football defensive back Al Worley, who had set an NCAA record– 14 interceptions in 10 games — that still stands after more than four decades.

By today’s standards, Hall had a relatively brief competitive career, retiring in 1970. But she packed her four years with massive achievement: three Olympic medals (2 gold, 1 silver), two world records, six American records, three national AAU titles, five Canadian championships, and three golds at the World University Games.

Strictly from a medal-haul perspective, Hall’s best performance came in the 1969 Canadian National Championships, when she won backstroke races at 100 and 200 meters, freestyle races over the same distances, and the medley relay.

Competing on behalf of the Tacoma Swim Club and coached by Dick Hannula, Hall’s last major competition occurred in Turin, Italy, in 1970, in the World University Games. There, she won the 100 backstroke, 400 freestyle relay and 4×100 medley relay, in a race in which was one of her relay partners was future Olympian and co-Man of the Year winner Lynn Colellaof the University of Washington.

A Wilson High of Tacoma graduate, Hall entered the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1979 and the State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 1983. But surely one of her best moments occurred after returning to the Northwest after her Olympic triumphs.

When she arrived at Sea-Tac, she was greeted by the Wilson High marching band. Two U.S. Navy helicopters then ferried Hall and her family to Cheney Stadium, where she was greeted by thousands of fans. Mayor A.L. Rasmussen gave her a key to the city.

1969 / TOMMY HARPER, Baseball

When, in late December 1969, Man of the Year voters bestowed the award on Tommy Harper of the expansion Seattle Pilots, they had no idea that the Pilots were already bound for Milwaukee, a secret agreement having been reached to sell the club to Brew City interests during the previous October’s World Series (see Wayback Machine: Dwyer KOs American League).

Had MOY voters understood that their major league franchise was about to be yanked after just one season, they might, out of spite, been inclined to go for any candidate other than a representative of a team about to jilt them.

On the other hand, 1969 had not exactly been a banner year athletically. Besides the impending move of the Pilots, the UW football team went 1-9, outscored 304-116 (the lone win came against 1-8 Washington State); the SuperSonics had finished 30-52, next-to-last in the Pacific Division, and the Totems stumbled in fourth in the Western Hockey League.

In addition to those bleak tidings, the UW football program was plagued by racial turmoil that had devolved into a player revolt.

MOY voters placed only four team athletes up for consideration: John Hanna (Totems), Lee Brock (UW football) and Lenny Wilkens (Sonics), in addition to Harper, and filled out the ballot with a trapshooter (Hugh Bowie), a golfer (Ken Still), a gymnast (Joyce Tanac) and a wrestler (Larry Owings), among others.

Tanac, who competed for the Seattle YMCA and University of Washington, would have been an excellent choice since she had done something unprecedented: At the 1969 AAU National Gymnastics Championships, Tanac had made a clean sweep of all five events, winning gold medals in the All-Around, balance beam, floor exercise, uneven bars and vault.

No wonder that Tanac, who began tumbling in Seattle at the age of 10, entered the U.S. Gymnastics Hall of Fame in 1990.

But given the sport he played, Harper had the higher profile among MOY voters. Although he hit just .235 in 148 games, he was the first player to come to bat for the Pilots when, on April 8, 1969, he led off in the top of the first against Jim McGlothlin of the California Angels.

In that inaugural plate appearance, Harper became the first Pilots player to record a hit, doubling to left field, and subsequently scored the Pilots’ first run on a home run by Mike Hegan.

Harper had gone on to steal an American League-high 73 bases (four in a game against the Chicago White Sox June 18, 1969), most in baseball since Ty Cobb swiped 96 in 1915.

The last Man of the Year of the 1960s, who made 50 starts at both second and third base, 21 starts in center and also saw playing time at both corner outfield positions, played eight more major league seasons after the Pilots became the Milwaukee Brewers.

—————————————-

ALSO SEE

Man of the Year Winners (1935-76)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year (1935-49)

Wayback Machine: Sports Star of Year: (1950-59)

Sports Star of the Year Winners (1977-2011)

—————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi.Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

——————————————-

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. The top-priced ticket includes admission to the show and the reception where complimentary beverages, including beer and wine, and heavy appetizers will be provided. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.

The Seattle Sports Star of the Year awards program is at Benaroya Hall Jan. 25. Created by Royal Brougham and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1936 and currently presented by the Seattle Sports Commission, the Star of the Year recognizes professional and amateur athletic achievement. Tickets can be purchased at benaroyahall.org or by calling 206-215-4747. The top-priced ticket includes admission to the show and the reception where complimentary beverages, including beer and wine, and heavy appetizers will be provided. You can find more information here. For information about how (and for whom) to vote, go to this page.