By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

The Pacific Coast League record book, especially the volume dedicated to the years 1903-57 (before the Dodgers and Giants moved west), is still peppered with the amazing feats of Vean Gregg, who might today be talked about in the same terms as Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander, but instead is considered one of the games most fascinating footnotes.

The reference to Alexander, who answered to Pete, is useful. Gregg and Alexander both arrived in the major leagues the same year, 1911, Gregg with the Cleveland Naps (now the Indians), Alexander with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Gregg threw left handed, Alexander right handed, and both produced startling rookie seasons, Gregg going 23-7, 1.80 to Alexander’s 28-13, 2.57. Three years into their careers, Alexander had 69 victories to Greggs 63, including 79 complete games to Greggs 71. But Alexander also had 38 losses, five more than Greggs 33, and Gregg sported the better ERA, 2.17 to Alexanders 2.57.

By the end of the first of those seasons, future Hall of Famers Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins were on record as labeling Gregg the best left-hander in American League, and Billy Evans, who umpired in the AL from 1906-1927, delivered this hosannah: I never saw a young pitcher grasp the finer points of the game or the weakness of the batters more quickly than the Western Wonder.” Evans added that Gregg is one of the greatest southpaws I ever called balls and strikes for.

Baseball writers of that era also buzzed over Gregg and Alexander, at least one pointing out that the 69 games won by Alexander and the 63 by Gregg between 1911-13 topped the first three full-season totals of Eddie Plank (60), Christy Mathewson (54) and Walter Johnson (53). Cy Young, who had an award named in his honor for ringing up 511 victories, was only marginally better with 72 wins in his first three years.

But there the comparison between the two young pitchers ended. Alexander went on to win 373 games (third most in history) in a career that lasted until 1930 and resulted in Alexanders induction into the Hall of Fame in 1938. Although imbued with a world of talent and confidence, Gregg, who last played in a major league game Aug. 25, 1925, won only another 27.

Born April 13, 1885 near Chehalis, Washington Territory, the marvelously named Sylveanus Augustus Gregg Vean comes from the middle letters of his first name — was the third of nine children born to Pennsylvania farmer Charles Gregg and Mary Adelia Gregg, who met her future husband four years after he arrived in Washington Territory in 1876.

Charles Gregg made his living as a farmer and supplemented the family income by taking on plastering jobs. Although son Vean received a bookkeeping diploma from Clarkson Commercial School (later Clarkson High School), in 1904, he never did a lick of bookkeeping. Instead, he adopted both of his fathers professions, plastering becoming his full-time job in 1905 after a short tenure at South Dakota State University.

By 1906, Gregg started playing baseball, almost exclusively on weekends and holidays, with semipro and town teams in Idaho, Montana and the Palouse region of eastern Washington.

Smart with a dollar, Gregg discovered he could make more money by accepting plastering jobs during the week and playing ball for $25 per game on weekends, rather than joining a league full time and plastering when time permitted.

Gregg’s career path changed in 1907, seduced by $100 per month, when he abandoned plastering and moved to Idaho to pitch semipro ball for the Lewiston town team.

By the end of Gregg’s first year, Joe Cohen, manager of Spokane Indians of the Northwestern League, offered Gregg his first pro contract. Gregg turned it down, judging the money (no figure available) insufficient.

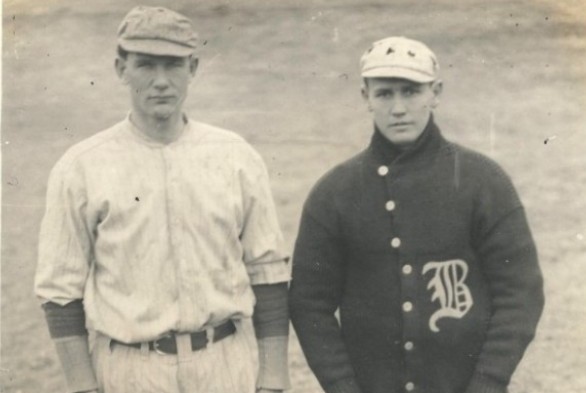

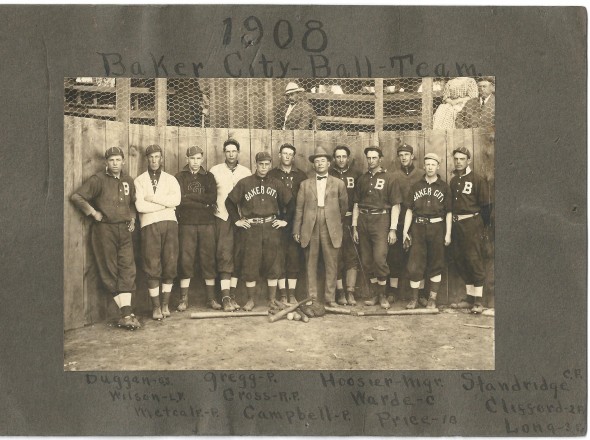

Instead, Gregg headed to Baker City, OR., of the Class D Inland Empire League, which is where he made his professional debut for the same $100 per month Lewiston paid him.

The Inland Empire League folded before the 1908 season ended, spelling the end of Gregg’s Baker City Nuggets, La Grande Babes, Pendleton Pets and the fabulously named Walla Walla Walla Wallas (or “Sweets,” as newspaper headline writers tagged them), whose best all-time player was probably Piggy Ward, who shares with Snohomish’s Earl Averill the MLB record of most consecutive plate appearances reaching base. From June 16-19, 1893, Ward officially reached 17 times in 17 appearances, getting eight hits, drawing eight walks and a hit by a pitch.

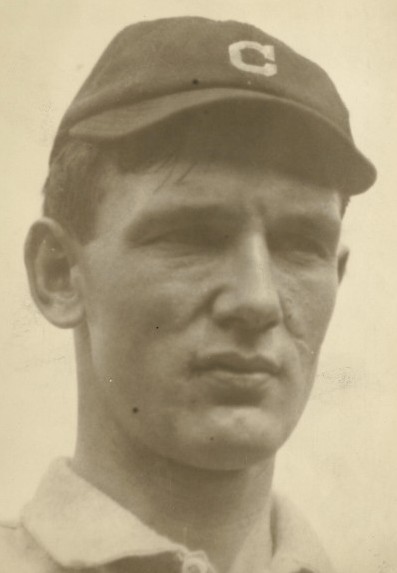

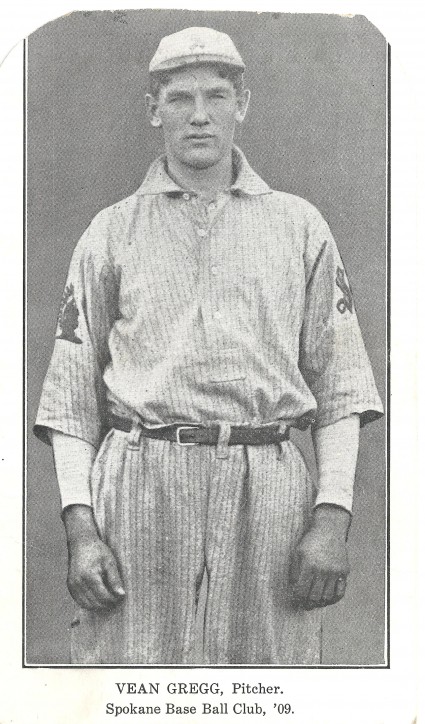

Portland manager Bob Brown cajoled Gregg into signing with Spokane of the Northwest League in 1909 by offering $185 per month. Gregg largely flopped, going an inexplicable 6-13 for a club that won 100 games (34.0 games above .500) and whose roster included William Hutchinson (Dode) Brinker, the first University of Washington graduate to reach the major leagues (Philadelphia Phillies, 1912).

Despite Greggs less-than-impressive record, which some attributed to a mysterious arm ailment, and some to too much practice, the Cleveland Naps outbid Pittsburgh and Detroit, buying Gregg from Spokane following the 1909 season for a reported $4,500 the highest amount ever paid for a West Coaster — and two players.

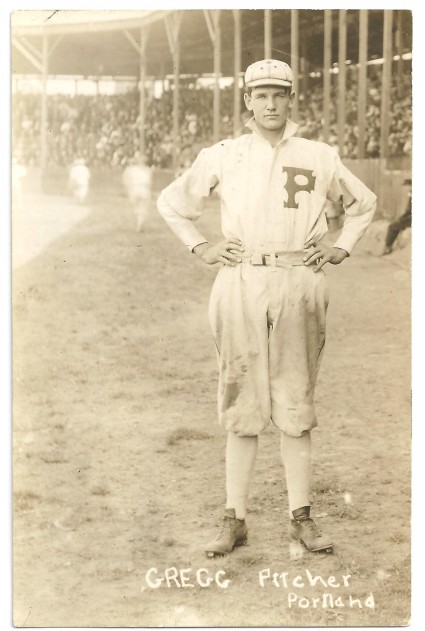

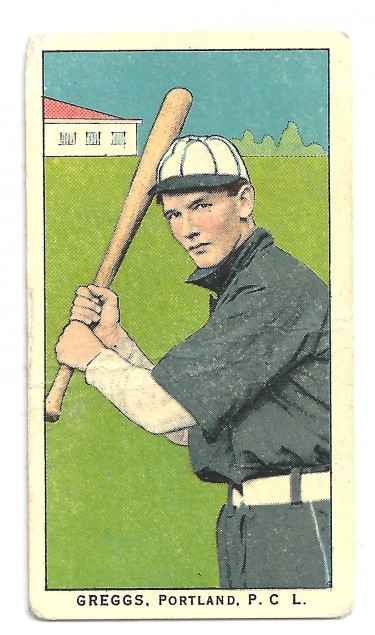

Cleveland offered Gregg a $250 per-month contract for 1910, but when Gregg refused to accept it, the Naps sold him on option to Portland of the PCL.

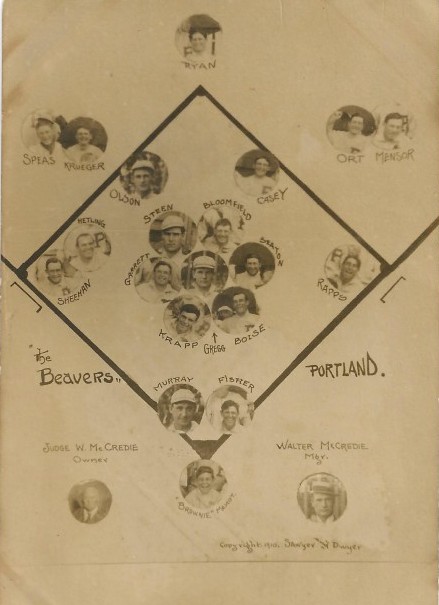

Thats when, at age 25, Gregg launched what became a sporadic but major assault on the PCL record book with an historic season. He won 32 games, 14 by shutout, a total that remains tied for the most in league history.

Gregg also led the league in innings (362.0) and strikeouts (364), became the first pitcher in PCL history to strike out eight consecutive batters, after he fanned the last man in the sixth through the first hitter in the ninth, Sept. 2 against the Los Angeles Angels. That game also marked Greggs first PCL no-hitter.

Gregg also threw three one-hitters, July 4 vs. Vernon and in consecutive starts Sept. 7 and Sept. 12 vs. Oakland, and recorded two of his 14 shutouts on the same day, against Sacramento Oct. 9, becoming the third PCL pitcher to accomplish such a feat. Portland won the PCL Championship.

Gregg’s 1910 season so impressed a Portland U.S. Census taker, according to the Society For American Baseball Research (SABR), that the census man listed Greggs occupation as star pitcher.

Gregg’s 1910 season was also enough to convince the Cleveland Naps that Gregg would make an adequate replacement for future Hall of Famer Addie Joss (even through Joss threw right handed) who, after battling injuries and illness in his final two seasons (1909-10), died of a bacterial infection April 14, 1911 at 31.

The Naps purchased Greggs contract from Portland along with Beavers teammates Ivy Olson, Gus Fisher and Gene Krapp. To complete the deal, the Naps paid the Beavers $4,000.

Gregg featured an excellent fastball (he told The New York Times he developed his arm strength while wielding a trowel when he worked as a plasterer) but his best pitch, by all accounts, was a curve, which he often used when he was behind in the count.

As umpire Billy Evans observed in one interview, Greggs nerve is unlimited. In one game against the Athletics, which I umpired at the plate, I saw Gregg on five occasions, with the count 3-and-2, use his curve in preference to grooving the fast one.

“On three of those occasions, a base on balls would have been costly, but each time he struck out the batter.

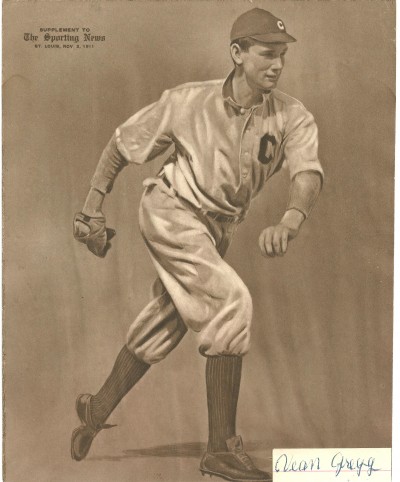

Upon joining a Naps team that included an almost-done Cy Young, an aging Nap Lajoie and 21-year-old Shoeless Joe Jackson, Gregg made his big league debut April 12, 1911 and allowed three runs in four innings of relief.

After punching out one of the American Leagues top hitters, Sam Crawford, twice in a second relief stint six days later, manager Deacon McGuire moved Gregg into the rotation. He won his first start, 5-2, against the White Sox.

By midseason, Gregg had the AL on its ear. He won 13 games in his first 22 appearances, prompting New Yorks Hal Chase to label Gregg, “The leading pitcher of the league, and in my opinion, the most marvelous southpaw I have ever looked at.”

It would, according to SABR, take 98 years before another left-hander, Matt Harrison (Texas, 2011) matched that feat (13 wins in first 22 appearances).

Gregg improved to 17-3 before he slumped slightly in late August. But he finished 23-7 for a Naps team that went 80-73 and would have fared far worse if Shoeless Joe hadnt produced 233 hits and a .408 average.

Gregg led the AL with a 1.80 ERA, beating out Walter Johnson (1.89), Christy Mathewson (1.99), Smoky Joe Wood (2.02), Eddie Plank (2.10), Chief Bender (2.16) and Ed Walsh (2.22).

Gregg also led the AL in WHIP (1.054), in fewest hits allowed per game (6.34), and in winning percentage (.767). His wins above replacement, 8.8, topped Johnson (8.2), Alexander (8.1) and Mathewson (7.7). When Randy Johnson won the 1995 Cy Young while pitching for the Mariners, his wins above replacement was 8.3.

Gregg also had a lot more innings pitched (244.2) than hits allowed (172). He particularly feasted on the White Sox, going 7-0 against them.

Here was a guy just three years removed from pitching in the deepest semipro bush (Baker City) in the-then remote Pacific Northwest. If the Cy Young award had existed, Gregg would have been a contender for the American Leagues version of it.

The Sporting News named Gregg to its All-American League Team and the Chicago Tribune wrote, Unless something unexpected happens, he promises to take his place among the great left-handers in baseball history.

Alas, the unexpected happened. No one, save perhaps Gregg himself, knew it at the time, but the key date in his 1911 season was Sept. 4. He pitched his final game, beating (again) the White Sox 9-2. Significantly, Gregg did not pitch after that due to a sore arm that developed, according to The New York Times, “almost overnight.”

Following a holdout that netted him a $3,500 contract, Greggs second season, a mostly pain-free 1912, failed to match his first, but he remained among the American Leagues elite, going 20-13 with a 2.59 ERA for a Cleveland team that went 75-78 despite his 20 wins and batting averages of .395 and .368 from Shoeless Joe and Lajoie, respectively.

That fellow Gregg is an exact duplicate of Waddell when the Rube was at his best, SABR quoted Naps manager Harry Davis as saying.

Gregg probably would have topped 20 wins, but a sore arm late in the year prompted several visits to famous Youngstown, OH., chiropractor John Bonesetter Reese.

Many baseball researchers have commented that the Naps enjoyed playing when Gregg pitched. He had, according to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, a habit of acknowledging good plays; he never criticized, regardless of the situation and he always encouraged anyone who committed an error.

The Plain Dealer also quoted umpire Evans as saying, Fans express the opinion that the Naps seem to play better ball behind him.

During the 1913 season, Gregg put together a string of 32.0 consecutive scoreless innings, struck out Ty Cobb three times in a game (Sept. 4), and pitched what probably was the greatest game of his career Oct. 13 at Forbes Field.

The Associated Press account, under the The Seattle Times headline, Pitchers Battle On Pittsburgh Soil, said, Cleveland defeated the Pittsburgh Nationals by a score of 1-0 in a game of 13 innings. It was a remarkable pitchers battle between Gregg of Cleveland, who struck out 19 men, and (Claude) Hendrix of Pittsburgh, who fanned nine batters. Greggs 19 strikeouts included two punchouts of Honus Wagner.

The New York Times attributed this statement to Bob Emslie, the home plate umpire that day: “I have seen all of the great ones: (Amos) Rusie, (Hoss) Radbourne and (Christy) Mathewson, but I am confident that I never saw any pitcher show the stuff that Gregg had.”

By the time the season ended, Gregg had set a mark that has yet to be equaled: By winning 20 games for the third year in a row, he became the only 20th-century pitcher to win 20 or more in each of his first three seasons.

Largely on the basis of those three years, Gregg is still Clevelands career won-lost percentage leader (left-hander), 98 years after he last pitched for the club.

Gregg started 1914 looking like he was headed toward another 20-win year. But after going 9-3 in 17 games, including 12 starts, his sore arm returned.

Fearful that Gregg’s woes would nag him forever, the Naps traded him to the Red Sox July 28 for catcher Ben Egan, pitcher Fritz Coumbe and Rankin Johnson.

The Red Sox, who knew about Greggs arm problems, gambled that he could be rehabilitated, and even paid his medical bills (not the normal practice in those days), figuring the investment would be worth it if Gregg returned to peak physical form.

Gregg visited several specialists, who more or less diagnosed that Gregg suffered from “rheumatism”, although modern researchers have speculated Gregg might have had a torn rotator cuff, which would have gone undiagnosed when he played.

In any event, Gregg tried to pitch through pain after his arrival in Boston, but could do no better than 3-4, 3.95 in 12 games, including nine starts, for a club that featured 19-year-old pitcher Babe Ruth and outfielder Tris Speaker.

Gregg never again had a big year in the majors. He enjoyed sustained periods in which his arm gave him no trouble at all, but others when it rendered him completely ineffective.

He went 6-7 combined over the 1915-16 seasons, years that Boston won the World Series, but he was so ineffective late in each season due to his sore arm that the Red Sox did not use him in the postseason in either Series. In fact, the Red Sox demoted him Buffalo of the International League late in 1916 (went 2-2 in four starts).

Gregg spent 1917 with the Providence Grays of the International League and, with no arm problems to speak of, enjoyed a great bounce-back season, going 21-9 and compiling one of the best strikeout records in International League history, fanning 249 in 265 innings. His best performance was Sept. 2, when he whiffed 20 Newark batters in a 1-0, 18-inning loss.

For the second time in Greggs career, a spectacular minor league season got him a ticket to the major leagues in 1918 with Connie Macks Philadelphia Athletics, for whom he made 25 starts.

The Athletics featured a .352-hitting first baseman named George Burns, who would later (1932-34) manage the Seattle Indians (see Wayback Machine: Red Killefer’s 1924 Indians).

But Greggs arm problems flared again and his comeback was generally not impressive (went 9-14, 3.12), although he threw a career-best, complete-game one-hitter June 3, beating Urban Shocker and the St. Louis Browns while hanging an 0-for-3 on George Sisler.

When the 1918 season ended, Gregg decided to retire to a 480-acre ranch in Calgary, Alberta, that he’d purchased in 1912. Gregg worked the spread for three years and might have remained a farmer if a combination of rising costs and falling prices hadn’t put him out of business.

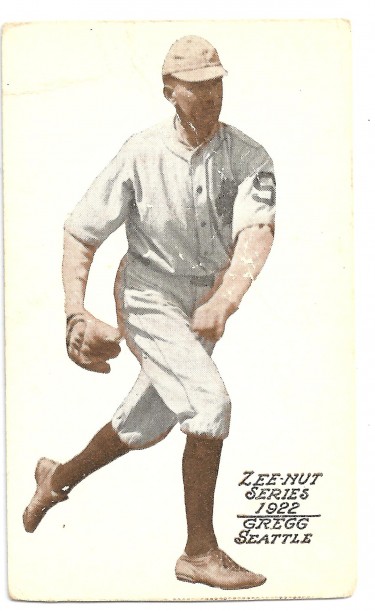

Needing work, Gregg joined the Seattle Indians in 1922, and the sports writers who covered the team promptly dubbed him The Alberta Ace.

Over the next three years miraculously, to use Greggs word he experienced no further arm problems and solidified his esteemed standing in a league in which he had never failed.

Gregg won 19 games in 22, another 17 in 1923, when he led the league in ERA (2.75), and 25 more with a 2.90 ERA in 1924 when he led the league in winning percentage (.694) and the Indians to their first Pacific Coast League championship. (see Wayback Machine: Red Killefer’s 1924 Indians).

Greggs 1924 effort on behalf of the Indians sparked a bidding war for his services. Washington owner Clark Griffith won, paying $10,000 and sending three players to Seattle for Greggs services.

Typical of Greggs career, he balked at the $4,000 salary Griffith offered, but eventually joined a team that included Walter Johnson and future Seattle Indians manager Dutch Ruether (see Wayback Machine: Walter Ruether, The Dutchman).

Six years after leaving the major leagues, Gregg appeared in 26 games for the pennant-bound Senators, mostly in relief. He went 2-2 with two saves and was optioned to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association just before the end of the season, which was why he missed playing in the 1925 World Series, just as he missed playing for the Red Sox in their World Series years of 1915 and 1916.

Gregg left major league baseball for good after 1925 with a career record of 92-63 (a .594 winning percentage) over 1,393 innings and 239 games. Gregg fanned 720 batters, walked 552, and gave up 1,240 hits for a WHIP of 1.286). At least one future Hall of Famer was not sorry to see Gregg depart: Tris Speaker went 1-for-10 lifetime against him.

But Gregg didnt leave baseball for good. In 1926, he hooked on with a Timber League semipro team in Aberdeen, WA., and in 1927 made a one-game appearance with Sacramento of the PCL.

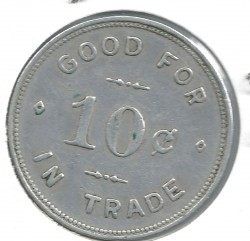

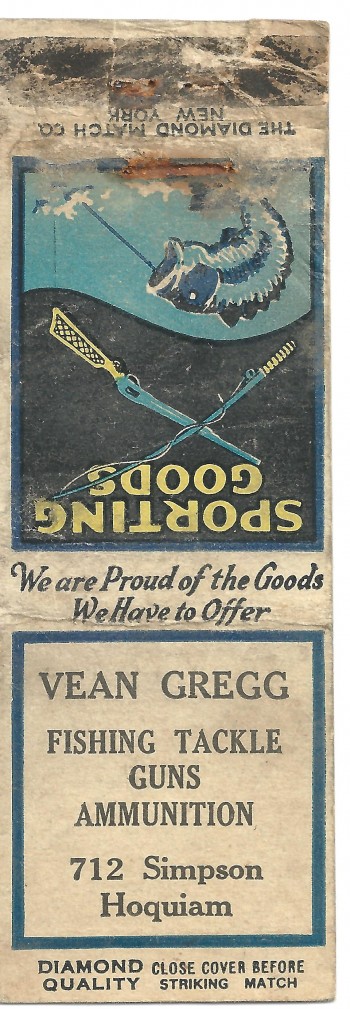

Gregg then returned to the Timber League, pitching through 1931, at which point he quit the game for good, sold his spread in Alberta and moved to Hoquiam, WA., where, for 37 years, he operated an emporium he called The Home Plate, which sold sporting goods (Gregg was an avid outdoorsman) and cigars and served lunch.

With one notable exception, most of the accolades that came Greggs way did so long after his death from prostate cancer July 29, 1964, in an Aberdeen assisted-living facility.

The Washington State Sports Hall of Fame inducted him in 1963, Gregg becoming just the second state-born pitcher enshrined following Fred Hutchinson (1960).

Significantly, Gregg entered the state hall before Johnny and Eddie OBrien, Hec Edmundson, Earl Averill and Bob Houbregs.

In 1969, Cleveland Indians fans, in a special vote, named Gregg the Indians greatest left-hander, which, as SABR noted, may say more about Cleveland pitching than about Gregg.

Over the years, Gregg entered a variety of halls of fame, including the Portland Beavers Hall of Fame, Inland Empire Hall of Fame and Northwest Baseball Oldtimers Association Hall of Fame.

In 2004, 40 years after his death, the Pacific Coast League inducted Gregg into its Hall of Fame. On that occasion, a Seattle columnist wrote that Gregg is one of the great — maybe the greatest — what-might-have-been stories in Pacific Northwest sports history.”

While Gregg had only three dominant years in the majors, they were good enough that Greggs 92 victories rank fourth on the list of most MLB wins by Washington state natives, trailing only Mel Stottlemyre (153), Gerry Staley (134) and Hutchinson (95).

Among state-born pitchers, only Gregg and Stottlemyre had a 20-win season. While each had three, Gregg became unique by doing it in his first three seasons.

Among the published works about Gregg, this unattributed assessment can be found: There are a lot of pitchers like Gregg. They are phenoms who develop arm trouble early and end up with short but flashy careers. It seems to be especially true of southpaws. Mark Prior, although not a lefty, is a modern version of the type. There are lots of others in the history of the game. With an ERA title in his rookie season, Gregg could easily be a poster child for the type.

The difference between Gregg and other “flashes in the pan” is there haven’t been a lot of pitchers like Gregg, if we are to believe published records, since few possessed the talent to compare favorably to Walter Johnson, Pete Alexander, Rube Waddell and Christy Mathewson. As umpire Billy Evans and a host others who saw him attested, Vean Gregg apparently did.

————————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

6 Comments

Cut line under the first pic of the trading token: “Home Plate trading token offered by Gregg at his Hoquaim sporting goods establishment. /David Eskenazi Collection”

It is, of course, ‘Hoquiam’.

Nice article.

Fixed, thank you.

Cut line under the first pic of the trading token: “Home Plate trading token offered by Gregg at his Hoquaim sporting goods establishment. /David Eskenazi Collection”

It is, of course, ‘Hoquiam’.

Nice article.

Fixed, thank you.

Excellent article, as always. However, I have a few issues

with this statement regarding Vean Gregg:

“While Gregg had only three dominant years in the majors,

they were good enough that Greggs 92 victories rank fourth

on the list of most MLB wins by Washington state natives,

trailing only Mel Stottlemyre (153), Gerry Staley (134) and

Hutchinson (95).”

“Mabton” Mel Stottlemyre garnered 164 wins for the Yankees,

1964-74, according to the Baseball Almanac. He dropped 139

decisions. Mel was born in Hazleton, Mo., according to

Wikipedia and Baseball Almanac. But baseballreference.com

lists his birthplace as Prosser, Wash. (To be a true “native” of a state

you have to be born there).

Mel’s son, Todd Stottlemyre, born in Sunnyside, posted a

career ledger of 138-121 from 1988-2002.

Hall of Famer Amos Rusie (the Hoosier Thunderbolt) is in the

Washington State Hall of Fame, although born in Mooresville,

Ind., sharing the same hometown as desperado John Dillinger.

Rusie was 246-174. He died in Seattle in 1942.

Oldtimer Ed Brandt, born in Spokane in 1905, was 121-146.

And how could you leave out Pasco’s Bruce Kison? He was

115-88 from 1971-85.

SRA/

Excellent article, as always. However, I have a few issues

with this statement regarding Vean Gregg:

“While Gregg had only three dominant years in the majors,

they were good enough that Gregg’s 92 victories rank fourth

on the list of most MLB wins by Washington state natives,

trailing only Mel Stottlemyre (153), Gerry Staley (134) and

Hutchinson (95).”

“Mabton” Mel Stottlemyre garnered 164 wins for the Yankees,

1964-74, according to the Baseball Almanac. He dropped 139

decisions. Mel was born in Hazleton, Mo., according to

Wikipedia and Baseball Almanac. But baseballreference.com

lists his birthplace as Prosser, Wash. (To be a true “native” of a state

you have to be born there).

Mel’s son, Todd Stottlemyre, born in Sunnyside, posted a

career ledger of 138-121 from 1988-2002.

Hall of Famer Amos Rusie (the Hoosier Thunderbolt) is in the

Washington State Hall of Fame, although born in Mooresville,

Ind., sharing the same hometown as desperado John Dillinger.

Rusie was 246-174. He died in Seattle in 1942.

Oldtimer Ed Brandt, born in Spokane in 1905, was 121-146.

And how could you leave out Pasco’s Bruce Kison? He was

115-88 from 1971-85.

SRA/