By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

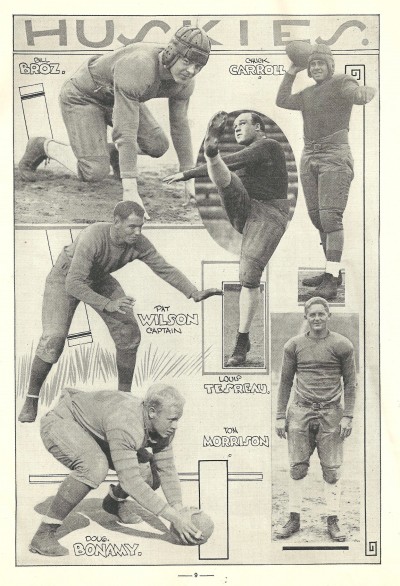

It’s not often that an athlete gets carried off the field on the shoulders of his admirers. Rarer still is the athlete who receives such treatment after a defeat. So imagine how great a game the University of Washington football star Chuck Carroll must have played Nov. 17, 1928 at Stanford Stadium in Palo Alto, CA.

That day, Carroll’s Huskies lost 12-0, and yet Carroll left the field not on the shoulders of his own teammates, but on the those of Stanford’s players, who had been urged to carry the UW halfback/linebacker off by President-elect Herbert Hoover, a Palo Alto resident and Stanford alum, who attended the game.

“That man is the captain of my All-America team,” Hoover gushed of Carroll, who, in a string of eight consecutive plays, made seven solo tackles and an interception.

“Carroll is a plugger of the first water on defense, a terror in all departments, even to passing,” sports writer Bill Heiser wrote in the next day’s San Francisco Examiner.

“Carroll has all of California singing his praises after his splendid showing when he kicked and passed, crashed the line and stopped many Cardinal plays.”

“Thousands thrilled to the playing of (UW’s) Johnny Stambaugh, the dashes of Chuck Carroll, and the passes from Carroll to Johnny Flannagan that for almost three quarters kept the mighty Cards at bay and made the game a scoreless tie,” opined The Seattle Times. “Washington outplayed Stanford almost the entire game only to have Don Muller, Stanford end, catch two touchdown passes late in the second half for a Card victory.”

“These old eyes have never seen a greater player. I don’t believe there is a better halfback in the entire United States. Carroll didn’t display a weakness,” said legendary Stanford coach Pop Warner, who coached two of the greatest players of the era, Jim Thorpe (Carlisle) and Ernie Nevers (Stanford).

Two weeks after the game, Warner, in collaboration with Notre Dame’s Knute Rockne and USC’s Howard Jones, named Carroll to his All-America first team.

That was one of 12 first-team All-America selections for Carroll in 1928, his third and final season as a Husky. The Associated Press, United Press, Saturday Evening Post and the All-America Board, among others, also selected Carroll, who had replaced a Husky legend, George Wilson (1923-25), and become one himself.

(Wilson made first-team All-America in 1925 and Carroll followed in 1928. They remain the only consecutive Husky running backs in school history named first-team All-America. To put that another way, UW has had two consensus All-America running backs in its 122 football seasons. The two, Wilson and Carroll, came in a five-year span between 1923-28.)

Born Aug. 13, 1906 in Seattle, Charles Oliver Carroll was one of five siblings of Thomas J. and Maude Carroll, who moved to the city in 1880 and founded Carroll’s Fine Jewelry, which had a 113-year run, including 95 on Fourth Avenue in the Joshua Green Building (Carroll’s Fine Jewelry is where Kurt Cobain purchased Courtney Love’s engagement ring in 1994).

Carroll, who grew to six feet and 190 pounds, attended Madrona Grammar School (future parking lot entrepreneur Joe Diamond was a friend and classmate) and began to get his name in Seattle newspapers in 1922, when he starred in football, basketball and baseball under Leon Brigham at Garfield High School.

By the time Carroll graduated, he earned 16 varsity letters and acclaim as the best all-around high school athlete in the city. He also served as editor of the Garfield High student newspaper.

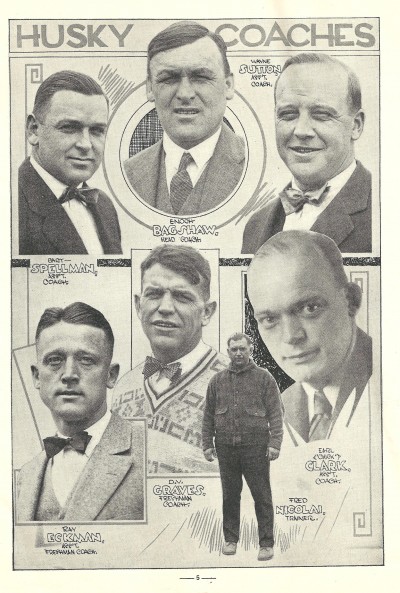

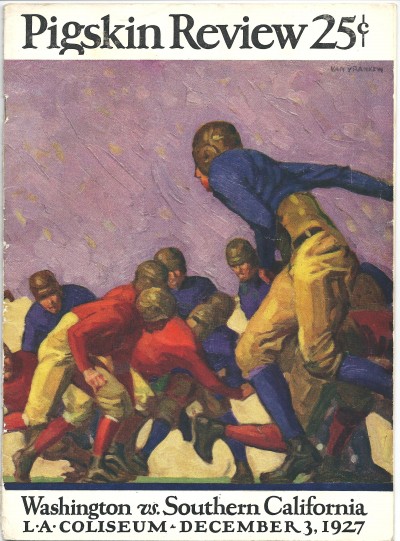

When Carroll enrolled at the University of Washington in 1925, the Huskies, under head coach Enoch Bagshaw, were just finishing up a fabulous, three-year run that included a 28-3-3 record (UW outscored its opponents, 1,102-107) and the school’s first two Rose Bowl appearances in 1924 and 1926 (see Wayback Machine: Bagshaw’s Roaring Twenties).

Bagshaw also produced his first All-America selection in Wilson, widely considered the greatest player in the football program’s first 35 years. No one could have imagined that by the time Carroll graduated many fans would consider him greater than Wilson (including Carroll himself).

In the 1927-28 seasons, Carroll tallied 32 touchdowns, 15 as a junior in 1927 and a school-record 17 in 1928 that stood as the school standard until Corey Dillon broke it in 1996.

During one game in the 1928 season, Carroll scored 36 of Washington’s 40 points against College of Puget Sound on six touchdown runs, all inside of 10 yards, another school mark.

Carroll, the Pacific Coast Conference’s leading scorer in his junior and senior years, had several staggering performances. In one of his most celebrated, he rushed for 136 yards (1oo-yard rushers were extremely rare in those days) and scored two touchdowns Oct. 22, 1927, in Washington’s 14-0 victory over Washington State in a game that drew a Seattle record crowd of 35,000.

In the 1928 Oregon game, Carroll made two out of every three tackles and drew this response despite Washington’s 27-0 loss:

“The greatest single athletic performance I ever saw involved Chuck Carroll right after he had been named an All-America,” said Win Bird, who became academic counselor for intercollegiate athletics at the University of Washington. “We were playing a great Oregon team in Multnomah Stadium.

“Chuck that day carried the football on 90 percent of the plays, and that is the truth. I am not exaggerating. He also made 60 percent of the tackles. Oregon beat us (27-0). But without Carroll, it would have been a massacre. He was covered with mud and blood, but he didn’t give up.”

Washington played 360 minutes of football in 1928 and Carroll played 354 (he sat out the final six minutes vs. Montana Oct. 13, a 25-0 UW victory). During Carroll’s three seasons, Washington had a 24-8 record. Teammates voted him the Flaherty Medal (most inspirational player) his senior year.

Following the final game of the 1928 season, Washington retired Carroll’s No. 2 jersey, making him the second player in school history with a retired number, following Wilson, whose No. 33 went out of use when he left school for professional football.

Roland Kirkby (1948-50), who wore No. 44, is the only other Husky to have his jersey number retired. Don Heinrich, Hugh McElhenny and a few other team leaders considered Kirkby such a great teammate that they petitioned athletic director Harvey Cassill to retire No. 44, which Cassill did (see Wayback Machine: The Harvey Cassill Era).

Although jersey Nos. 2, 33 and 44 are technically retired, they continue to be used. WR Aaron Williams (1979-82) wore Carroll’s No 2 and so does his son, current UW receiver Kasen Williams.

While Wilson had a brief NFL career with the Providence Steam Rollers (he led Providence to the 1928 NFL championship), Carroll was not inclined to play professionally after his UW career came to an end. There wasn’t enough money in the game in those days to make playing worthwhile, and Carroll had loftier ambitions.

After considering an appointment to West Point, Carroll entered the University of Washington Law School. After receiving his law degree in 1932, Carroll developed what became a flourishing practice in Seattle, interrupted when he entered the Army Judge Advocate General’s Dept. at the start of World War II.

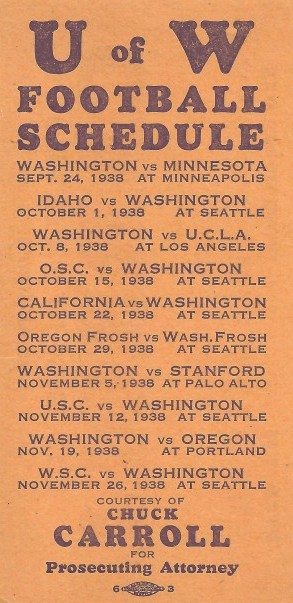

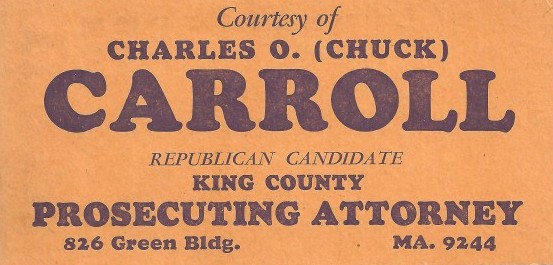

Five years later, most of which Carroll spent at the Presidio in San Francisco, he was discharged with the rank of colonel. In 1948, the King County prosecutor resigned to become a judge and the three King County commissioners selected Carroll to fill the vacancy. Carroll accepted the appointment and served for 22 years, winning numerous re-elections to the position.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Carroll became what historylink.org described as “one the most powerful men in Seattle and King County.” As King County prosecutor, he was the head of law enforcement in the county and had complete control of who would be prosecuted for crimes.

Carroll also served as head of the Republican Party in King County, a position that allowed him to approve or disapprove political appointments and candidacies.

As historylink.com reported, Carroll probably reached the height of his power in 1957 when he prosecuted powerful Teamster leader Dave Beck for grand larceny.

Beck had a large influence on the economy of Seattle and the Northwest for decades. Beck did not report for his prison term for five years, but the case demonstrated that Carroll feared no one.

Carroll’s career in public service ended in controversy when he was indicted along with 18 others in connection with a Seattle police scandal.

Officers were accused of taking bribes from tavern owners to tolerate illegal gambling and other activities, and Carroll’s detractors charged him with failing to prosecute police corruption vigorously.

“There was a culture of tolerance in the city,” former Seattle mayor Wes Uhlman told The Seattle Times. “It had been that way for many years. There was tacit agreement that officials would go after serious crime and leave the petty stuff alone.”

Judge W.R. Cole dismissed the indictment, but it cost Carroll politically. He lost by a landslide to Christopher Bayley for the 1970 Republican nomination for prosecutor. After his defeat, Carroll returned to private law practice until 1985, when he retired.

In 1986, Carroll told Don Duncan of The Seattle Times that he never condoned the “tolerance policy” that allowed small-stakes gambling.

“I said bring me the facts for a case (abuse of the system) and I’ll file it. I always worried that there might be payoffs to permit the stakes to go higher and higher. And that’s what happened. The names of some good people were dragged through the mud.

It took more than two decades after his athletic career for Carroll to receive official acknowledgement of his football exploits. In 1950, Garfield High selected him as its “Athlete of the First Half Century.”

“I’m so glad I went to Garfield,” Carroll said upon the occasion. “It was by far the most cosmopolitan high school in the state. We had whites, blacks, Japanese, Chinese, and it seemed as if all of us were colorblind. I’m sorry it isn’t that way anymore.”

Eight years later, the Helms Athletic Foundation inducted Carroll into its Hall of Fame. In 1964, he became the second Husky, following Wilson, to enter the College Football Hall of Fame (his hall class included famous Army coach Red Blaik and Kyle Rote).

In 1950, Carroll was named to Washington’s All-Time Team. UW fans voted on the squad and made Carroll a first-teamer, along with Wilson, who received the most votes, 10,282. Carroll received 7,658 and only two other Huskies, center Walt Harrison (9,246) and end Dave Nisbet (7,812) received more.

In 1979, Carroll became a charter member of the Husky Hall of Fame, beating out Wilson, who didn’t enter the Husky shrine until 1980.

Carroll missed out on one accolade, failing to make Washington’s All-Century Team, selected in 1990. The backs on that team included Wilson (1923-25) Hugh McElhenny (1949-51) and Joe Steele (1976-79).

Carroll never said anything publicly about his omission, but it rankled him severely when Wilson got the nod of “Player of the Century: First 50 Years.”

Carroll even telephoned the author of an article on Wilson’s selection and seared his ears.

“I was better than Wilson was,” said Carroll, in a testament to the confidence he had in himself.

Better in a lot of ways, although not necessarily on the football field. While Carroll became a prominent attorney and community pillar, the unfortunate Wilson frittered away what money he earned playing pro football (and wrestling professionally) and wound up an alcoholic. Carroll outlived Wilson, who died in 1963, by 40 years.

Carroll was a life-long Husky season ticket holder, watching every game with his wife, Alice Grangaard Carroll (Carroll nicknamed her “Granny”), and he lived a long life, to 96.

At 94, Carroll was asked what had appealed to him most about playing college football.

“I loved it,” he said. “You’d stand behind the line of scrimmage, and it was either him or you, and it wasn’t going to be him.”

On the morning of June 23, 2003, Carroll, in Swedish Hospital, slipped into a coma at about 5 a.m. and died about 7:55 a.m.

One of the last people to see him alive was Don McKeta, a star of Jim Owens’ 1960-61 Rose Bowl teams who had become a personal friend and visited often with Carroll.

“He was really a giant of his era, both in the sports and legal arenas,” said Norm Maleng, who also became King County prosecutor.

“He was tough, but he was honest and above-board,” said old friend Joe Diamond.

—————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Thanks for remembering a Husky legend. These are the stories behind the historical power and pride in the Purple and Gold. Still can’t get used to the new black uniforms the players seem to like. Go Huskies

Much as I’m a fan of Sportspress and Dave Eskenazi’s work, I have to alert your readers that this article’s treatment of Carroll and the well-documented history of widespread payoffs to police and many public officials in King County is naive at best. Carroll is dead, but it was the feds, not the King County Prosecutor, who in the main initiated the work that brought Dave Beck to justice and who began to end the payoff system in King County. Carroll obstructed reform. The P-I photographed a gambling kingpin visiting Carroll’s home. The fact that it took the feds to initiate reform should provide an accurate sense of history. Jim Lynch’s new novel, “Truth Like the Sun,” gets at self delusions regarding this chapter in Seattle history that, as this article sadly shows, persist to this day.