By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

It’s not often that a graduate of the University of Washington football program succeeds in the National Football League to a far greater degree than he did as a Husky. Most famously, that was the case with Warren Moon, whose play at quarterback under Don James in the mid-to-late 1970s provided zero hint that he had a Pro Football Hall of Fame career in front of him.

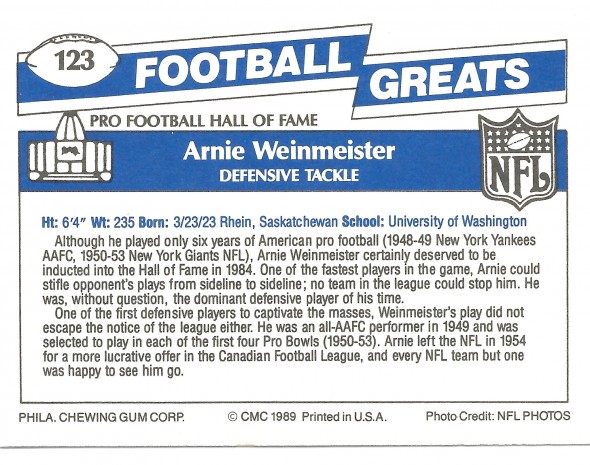

Ben Davidson had a similar story in the 1960s. A defensive tackle under Jim Owens, Davidson rarely started for the Huskies, never made an all-conference team and entered the NFL (New York Giants) as a fourth-round draft choice. Davidson didn’t start a game, with three teams, during his first five seasons, but developed into a three-time All-Pro who twice led the American Football League in sacks (1964-65).

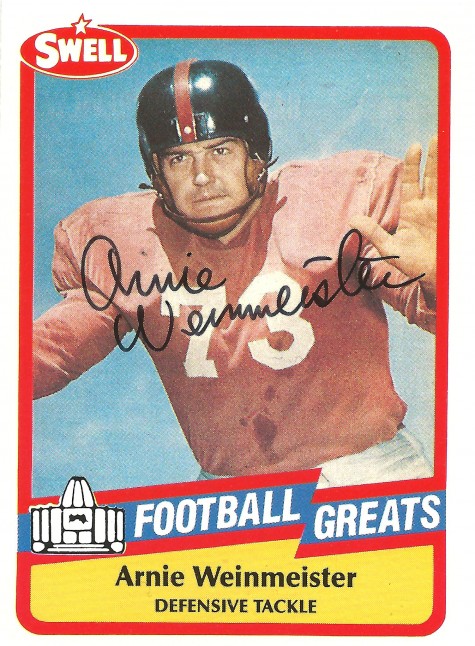

Two decades before Davidson and four before Moon, Arnie Weinmeister also went from a college career of no particular distinction – he was a 17th-round draft pick in 1945 — into an NFL career that landed him in the football shrine of Canton. Remarkably, Weinmeister’s professional experience amounted only to six seasons and 71 games, one of the shortest Hall of Fame tenures on record. Weinmeister obviously impressed a lot of people immensely.

Born March 23, 1923 to German immigrant parents in Rhein, Saskatchewan, Arnold George Weinmeister, one of eight children, moved to Portland with his family when he was a year old. He attended Portland’s Jefferson High School and twice was named an all-city tackle.

Weinmeister entered the University of Washington in 1941 to study math and economics and earned a football scholarship as a two-way end under head coach Ralph “Pest” Welch.

Weinmeister played just one season (1942) before, as with many of his teammates, he dropped out of school to join the military. Weinmeister missed the 1943-44-45 seasons, primarily serving with Gen. George Patton’s forces in France and Germany as an artillery officer (see Wayback Machine: Pest Welch’s Crazy War Years).

Weinmeister returned to the Huskies in 1946 following his military discharge in excellent shape and certainly better off than two teammates, halfback Fred Provo, wounded in the Battle of the Bulge, and end Jack Tracy, who took a bullet while serving in the South Pacific. Weinmeister had bulked up to 240 pounds (from 210), and Welch shifted him from end to fullback, a position Weinmeister always wanted to play.

In his first start at the position, against ex-UW coach Jimmy Phelan and the St. Mary’s Gaels, Weinmeister played so well that Ray Flaherty, coach of the New York Yankees of the All-America Football Conference (an NFL rival from 1946-49) and a former Washington State/Gonzaga player, described Weinmeister as “the best-looking fullback prospect in the country.” On the basis of Flaherty’s scouting report, the Yankees immediately acquired Weinmeister’s draft rights.

But the next week, during a 39-13 UW loss to UCLA at Husky Stadium, Weinmeister suffered a season-ending knee injury on a blind-side block in the third quarter that required surgery.

“They didn’t have knee operations perfected as they do today,” Weinmeister told Don Duncan of The Seattle Times in 1982. “It took me about a year to recover.”

When Weinmeister returned to the Huskies in 1947, his final year of eligibility, Welch, fearing that playing fullback would stress Weinmeister’s surgically repaired knee, shifted him to defensive tackle, a position he had not played since high school.

While Weinmeister played well enough as a senior to earn invitations to the East-West Shrine Game (see Wayback Machine: Hollingbery, Hein, Edwards) and College All-Star Game in Chicago, the pros didn’t pay him much heed, perhaps because Weinmeister, initially at least, had no desire to play in the NFL.

“I want to graduate in June and then get busy in the business world,” Weinmeister told The Seattle Times in April, 1948. “Football is great fun and the experience in professional football would be something to have, but after all, I have had enough play. It is about time for me to settle down to work.”

But Flaherty, who had selected Weinmeister in the 17th round (166thpick) of the 1945 All-America Football Conference draft, persuaded Weinmeister to forgo a business career for at least one year and give pro football a whirl. An $8,000 contract went a long way toward changing Weinmeister’s mind (the money also enabled him to purchase a used Pontiac sedan) and the only reason he received that much was because of the rivalry between the AAFC and NFL had escalated salaries.

“If it hadn’t been for the two leagues, I wouldn’t have played pro ball,” Weinmeister once told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “The salaries they were paying before (the rivalry) wouldn’t have interested me. It was a good thing for the players and in a way, for pro football, too. It brought a lot of fellows into the game who wouldn’t have considered it otherwise.”

Although Flaherty drafted Weinmeister primarily as a fullback/blocking back prospect, he soon shifted him to tackle, as Pest Welch had done. Late in 1948, Weinmeister’s first season with the Yankees, head coach Ed Strader, who replaced the fired Flaherty, told reporters, “He’s the greatest tackle I’ve ever seen. He has amazing speed. Except for Buddy Young, he’s the fastest player on the team.”

Few players have been as dominant at their position as Weinmeister was at his during his during his six-year stint as a defensive tackle that began with the Yankees and ended with the New York Giants in 1953.

Weinmeister made second-team All-AAFC as a rookie, followed by first-team All-AAFC in 1949, and then was a unanimous All-NFL choice all four seasons with the Giants. He also was selected to play in the Pro Bowl in each of his first – and only — four years in the NFL.

According to Pro Football Hall of Fame, Weinmeister was “one of the first defensive players to captivate the masses of fans the way an offensive ball-handler does. At 6-foot-4 and 235 pounds, he was bigger than the average player of his day and was widely considered to be the fastest lineman in pro football.

“Blessed with a keen football instinct, he was a master at diagnosing opposition plays. He used his size and speed to stop whatever the opposition attempted, but it was as a pass rusher that he really caught the fans’ attention. A natural team leader, he was the Giants co-captain in his final season in New York.”

When the All-America Football Conference collapsed following the 1949 season (the AAFC’s San Francisco 49ers, Cleveland Browns and Baltimore Colts joined the NFL), the New York Giants acquired negotiating rights to Weinmeister and several other ex-Yankees, including Otto Schnellbacher and Tom Landry, future head coach of the Dallas Cowboys.

Ted Collins, whose New York Bulldogs (as the Boston Yanks) chose Weinmeister in the NFL draft, was furious. Weinmeister himself was none too pleased when he discovered that the Giants intended to cut his salary by 30 percent. Nevertheless, in 1950 Weinmeister became a Giant. By the following year, he was earning $11,000 annually, top wages for a tackle in those days.

”It was a wonder to see him on the field,” said Dante Lavelli, the star end for the original Cleveland Browns, who lined up opposite Weinmeister when the Giants and Browns built their rivalry. ”He was one of the first big men who could move that quickly.”

Buck Shaw, coach of the San Francisco 49ers, said in 1954: ”Weinmeister is the outstanding tackle in the NFL. One man can’t handle him.”

“Arnie Weinmeister was a steam engine on the field,” said the Pro Football Hall of Fame in an article it published on his members. “Players would flip a coin to decide who would have to face the menacing defensive tackle head-on.”

Roosevelt Brown, the Giants’ longtime offensive tackle who entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1975, battled Weinmeister in practice every day and conceded that in Weinmeister he more than met his match.

”With Weinmeister, it was impossible to shake him off,” Brown told The New York Times. ”He was very, very fast and one of the toughest to go up against. Fortunately, I only had to do that in practice.”

Weinmeister, whose career with the Giants came in the last years of Joe DiMaggio’s tenure (1936-51) with the New York Yankees, played pro football far longer than he imagined he would. In fact, every off-season he mulled retirement and only returned to play because his salary continued to grow.

“At the end of every season I’d tell myself that’s the last one,” Weinmeister told the Post-Intelligencer. “And then when July starts to roll around and the camps are opening again, I start getting the fever again.”

During his career with the Giants, head coach Steve Owen played Weinmeister almost exclusively on defense. His rare speed and skill earned him top league honors from the start. He was chosen to the All-NFL every one of his four seasons, 1950-53.

”If you wanted to know where the opponent’s ball was, all you had to do was look for Arnie’s jersey number,” said Tom Landry, who played cornerback for the Giants during Weinmeister’s time in New York.

“Weinmeister rates as the best defensive tackle in professional football, and his teammate Al DeRogatis, is close behind,” declared Cleveland Browns coach Paul Brown in 1952, as he assembled an American Conference all-star squad to face the National Conference. “It’s going to be a real pleasure to have Weinmeister and DeRogatis on my side for a change. Perhaps I can find out what makes them so great.”

In the early winter of 1953, after Owen left the Giants, Weinmeister announced his retirement and became a candidate, at least according to media reports, to replace the fired Howie Odell as head coach of the Huskies. When the job went instead to UW assistant Johnny Cherberg, Weinmeister signed to play for one year with the Canadian Football League’s Vancouver (later B.C.) Lions.

Weinmeister also agreed to serve the Lions as an assistant coach for a salary of $15,000 per year, $3,000 more than the Giants had paid him in 1953. According to Lions head coach Annis Stukus, the $15,000 salary “made Arnie among the highest-paid football players in Canada.”

Weinmeister’s jump to the CFL provoked a howl from NFL Commissioner Bert Bell, who declared “war” on the CFL and threatened to steal as many Canadian players as possible. The Giants, meanwhile, took Weinmeister to court, suing him for breach of contract.

“I figured that there would be some attempt to restrain me,” Weinmeister told The New York Times, “although the Giants knew I wouldn’t play for them in 1954.”

A New York judge ultimately ruled that the Giants had not properly exercised the option they held on Weinmeister’s services and allowed Weinmeister’s contract with the Lions to stand. Weinmeister thus became the first NFL player to legally break a contract. According to Pro Football Hall of Fame executive director John Bankert, the Weinmeister case was a “precursor to modern free agency.”

In addition to a $3,000 annual bump in salary, Weinmeister’s move to Vancouver put him back in the Northwest, only a three-hour drive from Seattle, where he and wife Shirley owned a home at 4018 E. 45th Street.

Weinmeister lasted two years in Vancouver – his 1954 team went 1-15 with Weinmeister going both ways – and retired after the 1955 season.

During Weinmeister’s playing days, most NFL players had off-season jobs (Weinmeister’s top salary was $12,000). Weinmeister’s had hooked on with a grocery distribution company, where he first became involved with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

After leaving football, Weinmeister became an organizer for the Teamsters, who initially stationed him in San Francisco and assigned him the task of organizing non-union plants. He ultimately became director of the 13-state, 400,000-member, Seattle-based Western Conference of Teamsters in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. He also served as the union’s second vice president, was president of Joint Council 28, covering 20 Teamsters locals in Washington, northern Idaho and Alaska, and secretary-treasury of Local 117 in Seattle before retiring in 1992.

Only once during his time with the Teamsters did Weinmeister become involved in controversy. In 1988, when the Justice Department filed suit to remove the Teamsters’ senior leadership, charging that it had made a ”devil’s pact” with organized crime, it accused Weinmeister and the 17 other members of the executive board of failing to root out corruption.

Under a consent decree, scores of union officials were removed by overseers. Weinmeister remained in office after stating in a deposition that he had no knowledge of organized crime other than what he had read in the newspapers or had seen in “Godfather’” movies.

For most of his Teamsters’ career, Weinmeister negotiated contracts for health and welfare coverage, pensions and higher pay.

“He loved going to work in the morning because he knew he was going to help somebody,” said his second wife, Joey.

Weinmeister perhaps helped too well. In 1981, Business Week ran an article stating that Weinmeister and the Teamsters had negotiated such outstanding contracts and fringe benefits on behalf of workers that fewer and fewer workers were able to take advantage of those contracts and benefits.

“The companies are going outside, non-union, using any deception they can to avoid paying those contracts,” Weinmeister told Duncan. “Essentially, what we have done is to have a contract that is negotiated so well that very few companies can stand it and stay in business. That’s a difficult posture to be in.

“That’s pretty much what the United Auto Workers did, too. They have 26 personal holidays, and that’s 26 days of no work being performed. How can you possibly compete with foreign competition and produce cars when you’re paying your people not to work? There has to be a happy medium in there somewhere.

“Because of my size, which had been fine in pro football, I was tabbed a union goon. When you are as big as I am, there is always somebody who wants to challenge you, simply because of who you are. I’ve been able to avoid most of it.”

Only twice during his time with the Teamsters did Weinmeister move off the business pages and back into the sports pages. The first time occurred in 1962, when Weinmeister opted to become a part-time line coach for the Seattle Ramblers, who played in the Northwest League, an amateur grouping featuring ex-collegians.

For many years, Weinmeister believed he would never make the Pro Football Hall of Fame, attributing his snub to the fact that he had taken the NFL to court and busted his contract.

“There’s truth in that,” Weinmeister said in 1982. “Certainly a number of players are in the Hall of Fame who were second-team All-Pro at the same position for I was selected on the first team,” said Weinmeister. “Leo Nomellini is an example. He was always selected behind me. He’s in the Hall of Fame.”

But in 1984, Weinmeister learned he was elected to the hall in a class that included WR Charley Taylor, DB Willie Brown and Mike McCormack, a former offensive tackle for the Cleveland Browns and the president of the Seattle Seahawks.

On June 28, 1992, following a bout with cancer, Weinmeister died of congestive heart failure. He was 77 and survived by his wife, two sons (Hans, Jason), two daughters (Kirsten, Gretchen), eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi.Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com. Follow David Eskenazi on Twitter at @SportspressNW

1 Comment

Another underachiever in High School, (Renton) UW and the Rams was George Struger who at 6’5″ was an overpowering center for the hs basketball team taking theem to a state championship. Renton Beat Elma and their 7 foot center that took oxygen on the bench.