By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

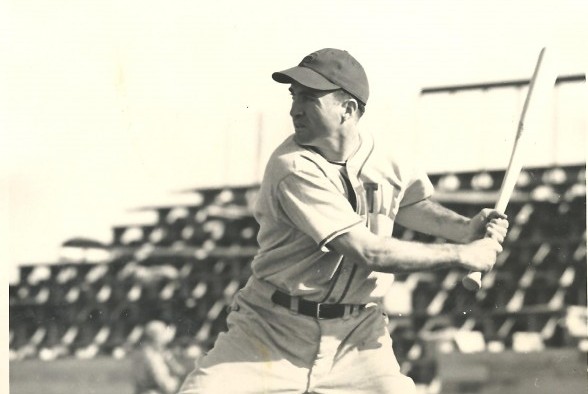

On the morning of May 29, 1948, a small group of boys, faces flushed with excitement, stood expectantly on the sidewalk in front of a white house at 2412 E. McGraw St. Inside, Hillis Layne, the Seattle Rainiers’ popular third baseman, donned a light raincoat to repel the dampness, picked up a baseball glove and stepped outside to greet the boys, who gave him a hearty cheer.

Layne led the boys to a grass field in the University Arboretum that served as the site of the unofficial “Hillis Layne Saturday Morning Baseball School for Montlake District Kids.”

The “H.L.S.M.B.S.M.D.K.” had come about a year earlier when youngsters discovered that the famous ballplayer lived in their neighborhood.

“Sure, the kids come around and beg me to play with them,” Layne told The Seattle Times. “I do it when I can because I remember how it was when I was a boy. I can’t turn ’em down and they do seem to appreciate it.”

When the Rainiers played a home series, Layne spent each Saturday morning at the field with the youngsters, knocking flies, pitching for both sides and passing out hints on baseball’s finer points.

“I remember when I was a kid in Tennessee,” Layne told The Times. “A lot of the boys would always say, ‘Let’s go to the river’ when it was hot. But I could never get interested in swimming. I just wanted to play ball.

“Those kids, you can’t fool ’em. They know everything about every ball player – his batting average, his previous record, things like that. But I enjoy playing with ’em. I don’t have anything to do in the morning. I figure I might as well get in some exercise.”

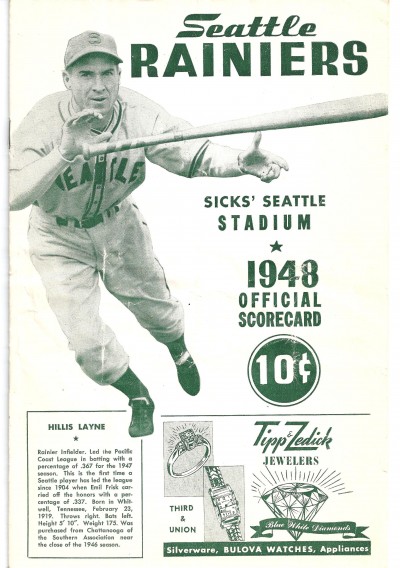

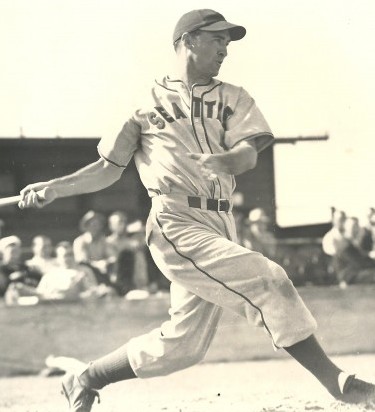

“Larruper Layne,” as the newspapers frequently referred to him, did not have a lengthy career with the Rainiers (1947-50), but while he worked in their employ few players had such a rapt following.

His Saturday morning work with youngsters drew wide publicity. He was gracious and cooperative with Seattle sports writers, who wrote glowingly about it. Above all, Layne could hit.

In fact, Seattle sports writers pinned the nickname “Mandrake” on him for his “magical ability,” as one scribe noted, to get on base. In his first year with the Rainiers, Layne produced a .429 on-base percentage while drawing just 50 walks.

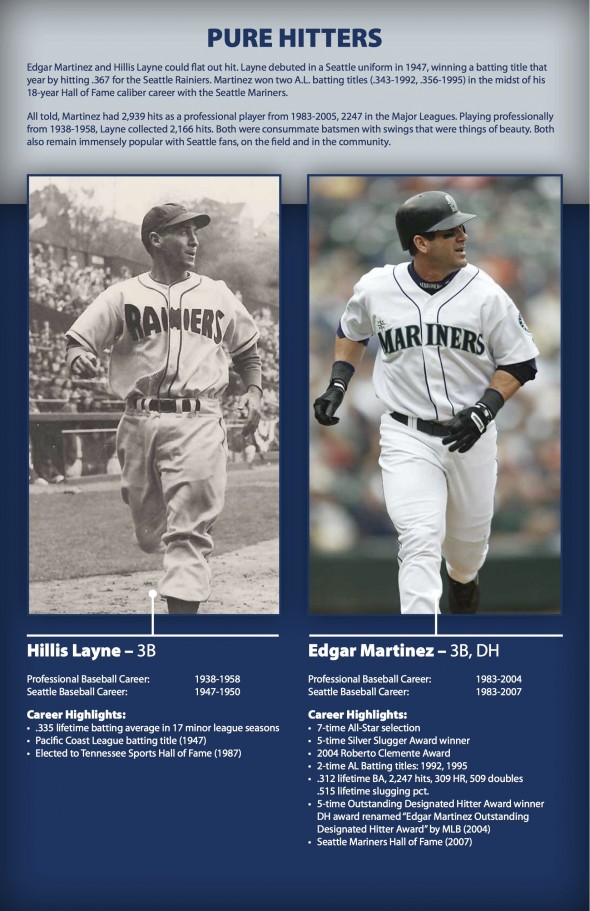

For a comparison, Edgar Martinez, a Mariner from 1987-02, had a career .418 on-base percentage while averaging 101 walks per 162 games played, which helps explain why a “Connecting The Generations” photo exhibit at Safeco Field pairs Layne and Martinez under the category of “Pure Hitters.”

The Rainiers – general manager Earl Sheeley at the controls — acquired Layne Sept. 29, 1946 in what started out as a straight purchase from the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern Association.

Eventually, the Rainiers had to send Chattanooga outfielder Kermit Lewis in compensation in order to complete the purchase, and did so largely at the urging of manager Jo Jo White, who played against Layne when White was with the Philadelphia Athletics and Layne with the Washington Senators in 1944.

“Layne is a fiery little guy who can play either third or second base and do a good job of it,” White said after club vice-president Torchy Torrance signed Layne to his initial Seattle contract. “He’s 5-foot-10, weighs 170, bats left and is a good hitter. He’s just what this club needs.”

Had Layne not been able to hit and reach base so effectively, he probably would have been doomed to laboring in coal mines in and around Whitwell, TN., where he was born Feb. 23, 1918 to Elijah Hudson Layne (1881-1969) and Dolly Daisy Elizabeth Hudson Layne and christened Ivoria Hillis Layne (friends mostly called him “Tony”).

Layne, sixth of eight children, had such a knack with a bat that in 1938 Joe Engel, president of the Lookouts, signed him out of Whitwell High School for $85 a month and assigned him to Class D Americus (GA.) of the Georgia-Florida League.

Layne batted .315 in 112 games and two years later joined the Class 1-A Lookouts. After hitting .307 in 60 games and .338 in 142 in 1941 for future Hall of Famer Kiki Cuyler, he received a late-season summons from Chattanooga’s parent club, the Washington Senators.

Layne’s big chance didn’t last long, just 13 games. Then, as with many major leaguers of that time, his career went on hiatus, interrupted by World War II.

Serving in the army, Layne did not see a ballpark again until late in the 1944 season when he rejoined the Senators following his discharge from the military, his exit from the service due to a leg injury.

Layne played only 33 games for the 1944 Senators, hitting .195 as he tried to find his stroke after a three-year absence from baseball. In 1945, he came back and hit .299 in 160 games and produced two highlight moments.

On Aug. 13, Layne went 5-for-5 against the old St. Louis Browns. Two weeks later, in the second game of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium, Layne hit the first – and only — home run of his big league career, a solo shot off Tiny Bonham.

In 1946, the Senators farmed Layne back to Chattanooga, where he picked up another nickname, “The Chattanooga Choo Choo,” and hit .369. But he never again received another shot at the majors, and at the end of the season the Rainiers acquired him.

As White figured, Layne fit in perfectly on a club that starred Lou Novikoff, who hit .325 with 21 home runs and 114 RBIs. Layne didn’t hit for that kind of power, but was constantly on base (see Wayback Machine: ‘Mad Russian Lou Novikoff’).

By mid-June, player-manager White and Layne led the Pacific Coast League batting race with .360 and .349 averages, respectively. By July 17, White had faded to .308 while Layne had surged to .354, 15 points behind Eddie Fitzgerald of Sacramento at .369.

“Dawg-gonedest guy I ever saw,” said player/manager White, who had spent nine years in the major leagues, mostly with Detroit. “Move your outfield to the right, he hits to left. Move ’em to the left, he pulls to right field. Move ‘em back, he drops the ball behind the infielders.”

“Little Hillis Layne is not a fearful slugger, but he’s always in those upper .300s when it comes to hitting,” wrote Lenny Anderson in The Seattle Times. “He’s always on base, always coming across the plate when someone hits behind him.

“A check of his record indicates he has been a high .300 hitter in every league he played in except his stretch in the majors. And even in the big time, he hit .299 for Washington that year.”

Layne took over the PCL batting lead Aug. 19 with a .364 average to Fitzgerald’s .356, and wound up leading the league with a mark of .367, four points higher than Fitzgerald’s .363.

He became Seattle’s first batting champion since Harlin Pool tied for the league lead (.334) in the last year of the Seattle Indians (1937), and the first outright winner since Art Bues hit .352 for Dan Dugdale’s 1911 Seattle Giants of the Northwest League (before Bues, Emil Frisk of the Seattle Siwashes won the PCL batting title in 1904 with a .336 average).

Although he hit left-handed, Layne favored slapping the ball into left field.

“Generally, the Rainiers’ foes played Layne well to the left, trying to head off the rash of bothersome line drives he sprayed to that side,” The Seattle Times explained. “But every once in a while, usually in even-numbered years, Layne got his bat all the way around on a ball.”

May 22, 1948 was just such a day. In the 10th inning of a tight pitching duel between Herb Karpel of the Rainiers and Red Adams of the Los Angeles Angels, Layne pulled his second home run of the season into the right-field seats to break a 3-3 tie and give Seattle a 4-3 victory.

Layne hit .324 in 1948, his second season with the Rainiers, then dropped to .289 in 1949, when the club decided to oust long-time fan favorite White as manager. In 1950, the club hired Paul Richards, who wasn’t a popular choice with the players.

“He kept everyone on edge with caustic comments and his growing impatience as the losses mounted,” author Dan Raley wrote in his epic on the club, Pitchers of Beer. “It got so bad the Seattle players were ready to mutiny.”

Raley quoted Layne as saying, “We lost about 10 straight, and one of the players, I won’t tell you who, said, ‘I wish we could lose 20 straight because of him.’”

“Layne wasn’t a huge fan of the manager, either,” Raley continued. “Richards never warmed to him, releasing the veteran infielder during the season, allowing Portland to quickly sign him on the rebound. The Tennessee native previously had been Seattle’s best hitter.”

Richards pulled the plug on Layne April 27, 1950, after Layne uncharacteristically dropped a fly ball in a 10-3 loss to the San Diego Padres.

“I enjoyed Seattle better than I did the American League,” Layne told The Seattle Post-Intelligencer. “I know I wanted to play there forever.”

“It is with genuine regret that one watches the passing from the Seattle scene of Hillis Layne, a prince among men, an uncanny hitter and a fielder whose defensive abilities are no longer up to AAA standard,” Anderson wrote in The Seattle Times on the occasion of Layne’s exit.

“A clutch hitter, Layne once promised his teammates he would come up with a home run to end an extra-inning game in Los Angeles, then proceeded to blast one over the right-centerfield fence,” sports writer Alex Schults wrote in The Times after Layne’s Seattle career ended.

“He liked nothing better than to step into the batter’s box at Sicks’ Stadium and catch a glimpse of Mount Rainier before turning his attention to the opposing pitcher.

“One is forced to remember the unnumbered situations in Seattle with the soft-spoken Southerner, falling away and chopping base hits into left field and left center, seemed to get on base every other time or so. Whatever his shortcomings in the field, he has been a most excellent hitter in his time.”

After playing in the Class B Tri-State (Anderson, IN.) and Class C Longhorn (San Angelo) leagues in 1953-54, Layne returned to the Pacific Northwest and became player/manager for the Class B Lewiston Broncs of the Northwest League.

He stayed there for four seasons (he won the league batting title in 1955 with a .391 average and finished second in 1956 at .354 and 1957 (.340). In those four seasons, Layne’s batting average was .362 and his on-base mark .468. He struck out only 78 times in four years and led league third basemen in fielding in 1955-56-57.

When Layne resigned in Lewiston to become a scout for the Kansas City Athletics, he had a .335 lifetime minor league average with 18 home runs in 17 league seasons.

Layne toiled 18 seasons as a major league scout, most of them for the Texas Rangers after stints with the Washington Senators and New York Mets. He retired in 1976 and returned to his native Tennessee after spending 40 years as a player, manager, coach and scout.

Even that wasn’t the end. For 15 years Layne managed a commercial league team sponsored by Ira Trivers, a Chattanooga clothing store.

Layne entered the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame in 1987, shortly after he was recognized by the Society for American Baseball Research as one of the top 100 minor league players of all time.

He died Jan. 12, 2010 in Signal Mountain, TN., at 91, two days after suffering a heart attack. He is interred at Chattanooga National Cemetery in Chattanooga.

In one of his last interviews, in 2008 with The Chattanooga Times, Layne spoke for an entire generation of ballplayers when he said, “When I played baseball, it was a great time to play. We just played with plain old balls and bats. We didn’t know anything about bonuses. We played for the love of the game.”

——————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out Davids Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com