By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Four years ago, in connection with the annual Star of the Year awards program, the Seattle Sports Commission conducted an online poll asking fans to vote on the top sports story of the previous 75 years. The commission sorted through dozens of potential stories, finally arriving at a list of 10 finalists. These were the 10 offered to voters for their consideration, listed in chronological order:

- Aug. 19, 1938: Fred Hutchinson’s 19th win on his 19th birthday for the Seattle Rainiers.

- March 20-22, 1958: Elgin Baylor and Seattle University’s advancement to the NCAA Tournament final opposite Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky Wildcats.

- July 19, 1958: The Washington varsity eight’s shocking upset of Leningrad’s famed Trud Club in Moscow.

- Jan. 1, 1977: The University of Washington’s 27-20 Rose Bowl victory over Michigan, which launched the Don James era.

- June 1, 1979: The Seattle SuperSonics’ NBA championship in six games over the Washington Bullets.

- Jan. 3, 1992:The University of Washington football team’s 1991 co-national championship.

Washington long jumper Phil Shinnick established what he thought was a world record of 27-4 at the California Relays in Modesto, CA., May 25, 1963. / University of Washington - Oct. 8, 1995: The Seattle Mariners’ first AL West championship, achieved by defeating the New York Yankees in the Kingdome on the most remarkable play in local pro sports history, the Edgar Martinez double.

- Oct. 12, 2004: The Seattle Storm’s first of two WNBA championships.

- Jan. 22, 2006: The Seahawks’ victory in the NFC Championship, sending them to Super Bowl XL.

- March 19-Nov. 22, 2009: The Seattle Sounders’ remarkable inaugural season, which included the franchise’s first U.S. Open Cup title and record attendance.

Star of the Year founder Royal Brougham, who covered the race for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, probably would not have been surprised that the majority of 30,000 Star of the Year voters went for Al Ulbrickson’s rowers, who made July 19, 1958 one of the most triumphal days in UW sports history.

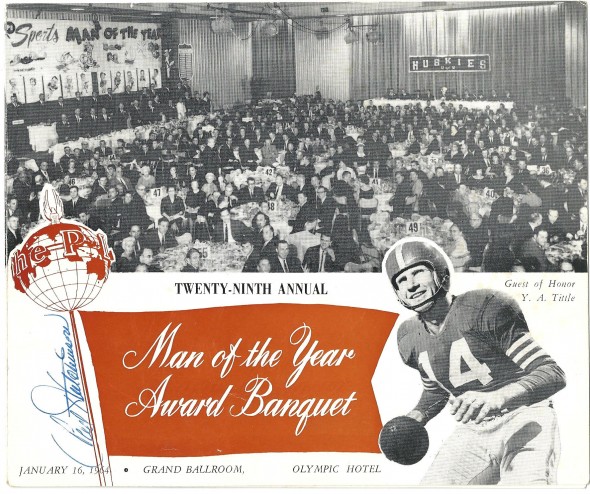

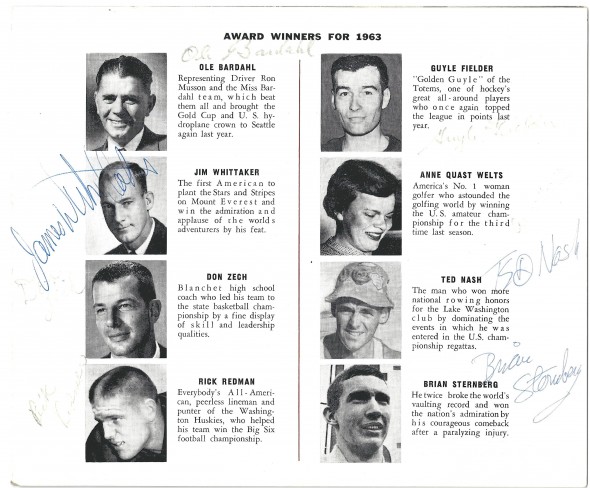

May 25, 1963 didn’t make the cut for the top 10 sports stories, but in many ways the events of that day remain as remarkable as any on the list. The details are not as well known, in part because the two principals, Brian Sternberg and Phil Shinnick, participated in a sport – track and field – that is now relevant to the public only in Olympic years and rarely received marquee billing in its heyday.

But track and field was a far bigger deal in their time, and Sternberg and Shinnick were two of its brightest young performers. On the date, they were University of Washington sophomores, 19 years old. They were friends, roommates and strong candidates to represent the U.S. at the following year’s Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

Sternberg and Shinnick began May 25, 1963 in Berkeley, CA., not long after dawn, where they were to compete in the Big Six Track and Field Championships, the name of the annual conference meet in those days. One a world record holder and the other undefeated, both were favored to win their events.

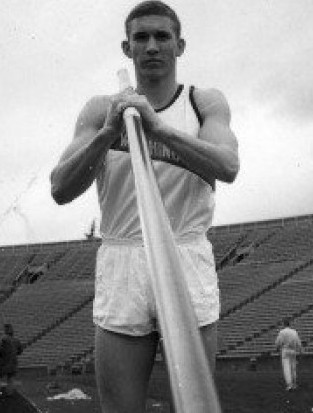

A Shoreline High graduate, Sternberg emerged over the previous two years as one of America’s most accomplished young pole vaulters. In his senior year, 1961, he became the first Seattle prep to surpass 14 feet when he cleared 14-2¼ May 5 in the Metro League’s Northern Division championship meet. His first collegiate success came as a Husky freshman in 1962 when he cleared 15-9 and then won the NCAA Indoor title with a vault of 16-3½.

Sternberg then established a world outdoor mark by clearing 16-5 at the Penn Relays in Philadelphia April 7, 1963, snatching the record from Finland’s Pentti Nikula, whose 16-2½ had stood for a year.

Sternberg subsequently lost his record to John Pennel of Northeast Louisiana, but had been vaulting well enough to reclaim it.

Shinnick, who starred in football, basketball and track at Gonzaga Prep, never came close to threatening Russian Igor Ter-Ovanesyan’s world mark of 27-3¼ in the long jump, but, like Sternberg, had announced himself as a coming force. Three weeks earlier, he had gone 25-2 in a dual meet with Oregon. Then, at the Far West Track Championships in Pullman May 18, he soared 25-5, defeating UW teammate Wariboko West, a Nigerian exchange student, and Oregon’s gifted Mel Renfro, who posted 24-5½ and 24-3½ marks, respectively.

Although Shinnick did not look forward to jumping so early in the day, 9 a.m., he felt primed to bust a long one, as he explained in an unpublished manuscript he wrote years later.

Shinnick disclosed that he expected to reach 26 feet despite the early start and even though he felt like he would be jumping uphill after initially scanning the runway and pit. Shinnick came close to his goal on a couple of scratches and then hit one of exactly 26 feet, a personal best and an astonishing four feet beyond Renfro, a future pro football star, and everybody else in the competition.

“I felt very happy,” Shinnick said. “I didn’t foul and my feet sailed past the white marker. I couldn’t believe this, my fifth varsity meet, and 26 feet already. As my feet sank into the soft sand, I tried the Ter-Ovanesyan landing and exit I’d seen in film. I rotated as I landed, then I bounded straight up in the air and let out a war whoop, and became like a pogo stick hopping around with glee.

“The official stared at me in disbelief. I could see a big space of four feet between my landing and everyone else’s. I could also see my spike marks in the board and no smudge on the putty over the board. The official still stared at me and I didn’t see them measuring the jump. What luck. I gazelled to my sweats and scooped them up.

“I needed to go tell Brian that he better jump well or I would be ahead of him. Then I saw the official raise a red flag to disallow my jump. I raced back to the pit and my glee turned to anger. How could he do this? I did not foul. I charged the official to protest. Just before I got to the official whom I wanted to tackle, Stan Hiserman (Washington’s head track coach) bear-hugged me. I tried to break his hold before they raked my mark away in the pit.

‘”I didn’t foul, you can see my spike marks on the board,’” I pleaded with Hiserman.

“They started to rake my mark away. I felt helpless and taken advantage of.”

“The official admits you didn’t foul but says you didn’t have your balance,” Hiserman told Shinnick.

‘“Listen to me, Phil. I have a plan,’ Hiserman said. ‘Leave the official alone. I’ll put a mark (a small, white piece of paper) two feet behind the board and you can still win and qualify for the final. Everyone is jumping four feet back.’

“I didn’t like his idea. I turned and watched them rake the best jump of my life away.”

On Shinnick’s ensuing jump, his feet struck sand 24 feet from the starting board, but his heels slipped under him and he fell back, his shoulder touching at 21-5½. And that was that. He missed qualifying for the final by a half an inch and was suddenly – shockingly to Shinnick – no longer undefeated.

“I searched for the official and he refused to look at me,” Shinnick continued. “Hiserman didn’t say a word. I went into shock. There is no ‘balance’ rule. One makes marks in the sand, one exits the pit sideways so as not to make a mark behind the heel marks. That’s it. Don’t go over the board. Why did the guy do this? I was a bit of a maniac and I didn’t have my balance, but it was a good jump.

“Everything became a big blur after that. Hiserman put me in the high jump, I made 6-6 on my first attempt and don’t remember any other jumps.

“He (the official) took away my mark because I expressed myself like a lunatic (today’s equivalent of a celebration penalty), a bouncing bozo,” said Shinnick. “To get a good mark and have it recognized became my heart’s desire. I felt wounded, as if I’d been hit by a car . . . I was sent to the dunce room for violating that official’s sense of good form. Who needs to look pretty? I wanted the long measurement.”

Sternberg fared better, but not much. He never could get his steps down, missed twice at a moderate height and didn’t get near 16 feet (15-9), much less his personal best of 16-5. He finished second.

“Brian was in a bad mood, and we didn’t talk,” said Shinnick.

What Shinnick didn’t know then was that the red flag that wiped out a perfectly legal and career-best 26-foot jump was not the worst thing that would happen to him that day.

Following the Big Six meet, Hiserman told Shinnick and Sternberg that the two of them had been invited to compete that night in the California Relays in Modesto, 90 miles away. Most of the world’s best track and field athletes would be there, including super miler Peter Snell of New Zealand, world 100-meter record holder Bob Hayes, and Ralph Boston, the American record holder in the long jump.

By the time Sternberg, Shinnick and Riserman arrived in the San Joaquin Valley, the long jump had already started, and Shinnick was placed in the last flight, just ahead of Boston, the first man to jump 27 feet.

“The other competitors had all jumped once. None had jumped well,” said Shinnick. “I knew what I could do.”

Trouble was, nobody else besides Sternberg and Hiserman knew what Shinnick could do, and that would become the crux of his problem.

Boston had already made one jump, a legal 26-0, when Shinnick eyed the runway. He would have recorded the best mark of his life – 26-8 — if he hadn’t scratched, but he did. He even checked to see if he had left spike marks in the putty, noting that he had, about a half an inch over the board. As a precaution, Shinnick removed a piece of white tape marking his personal starting position and set it back two inches.

Sternberg, who watched Shinnick’s first jump, jogged by to check on his roommate, squatted and plucked up several blades of glass between his thumb and forefinger and dropped them to gauge the wind. The grass blades fluttered to his feet. Good. No wind. It was time to jump, and with a two-inch safety zone, Shinnick knew he wouldn’t foul.

“If I break the world record in the long jump,” Shinnick said to Sternberg, “you have to do the same thing in the pole vault.”

“You got a deal,” Sternberg replied, smiling, as the Washington sophomores shook hands.

Ter-Ovanesyan set the world record of 27-3 ¼ July 10, 1962 in Yerevan, Armenia. Boston, the first man to jump 27 feet, held the American mark of 27-1½, established a year earlier in the same Modesto pit Boston and Shinnick were negotiating. Knowing nothing about college sophomore Shinnick, the Modesto crowd urged Boston to reclaim the world mark from the Russian.

Back behind the runway, Sternberg picked up more grass and tossed it, giving Shinnick a thumbs up.

“I felt strong and fast,” Shinnick wrote. “I knew I would do well. I could feel it in my bones. I fully understood that I had been given a second chance, in one day. It was unheard of. What a stroke of luck.”

Shinnick felt so good he wondered if he would get hurt if he jumped entirely over the 30-foot pit. He had cleared a shorter pit once, in high school, when he set a Spokane city record. Then, from the head of the runway, he rocked back and forth and lurched forward.

“I hit the board perfectly, I could tell,” Shinnick said. “It was as though someone had lifted me from behind, and pulled me toward heaven. I rose above those around the pit. My hips soared over their heads, I heard the crowd roar as I was airborne. I stayed up, and soared out.

“The crowd screamed. Not a perfect jump, but fair and in control. Not as at Berkeley, where I muscled for every inch. I looked to the side, fearful of disqualification, afraid to celebrate. Ralph ‘Hawkeye’ Boston eyed my marks in the pit; his eyes returned to me and the footprints again.

‘“Phil, you got the record!”’

The measurements: 27-9 on Shinnick’s right foot, 27-5 on his left. Other officials measured again and again, to make the final ruling. The sand finally caved in a little, and the officials jumped out of Shinnick’s imprints. The final marking: 27-4, a world record by three-quarters of an inch. Shinnick turned to Sternberg.

“I told you so, so it’s your turn to go. I looked at his eyes and knew that he could do it.”

Meet officials quickly whisked Shinnick, still wearing his spikes, to a press box at the top of the stands to face rows of disbelieving sports reporters, who demanded to know who Phil Shinnick was and how he had been able to jump 27 feet when he had only jumped 21-9 that morning in the conference championships.

“It was only much later that I came to understand the effect such disbelief would have on me and on my record,” Shinnick said.

Less than an hour later, Sternberg reclaimed the world record in the pole vault, riding his fiberglass pole 16-7, taking the world mark away from Pennel, who matched Sternberg vault-for-vault until the bar reached 16-7, a height Pennel missed three times.

On a day when four world records fell, and in a meet that featured Snell as well as the world’s fastest man, Hayes, Shinnick was elected Best Athlete of the Meet.

That night, Shinnick and Sternberg stayed at a motel just outside of Modesto, close to a grove of orchard trees, and spent most of it trying to walk off aches and soreness. Neither could sleep because of the day’s excitement.

“After our bet I really felt the pressure, but after how bad I did this morning I wanted to redeem myself like you did,” Sternberg told Shinnick. “I still had to beat John Pennel and his world record. My run up was very fast and I had to keep putting my mark back on the runway. I feel like I can go much higher. 16-7 is just my beginning.”

Still in their UW track suits 19 hours after they had been taped up for the Big Six meet, Sternberg and Shinnick talked through the night, about a lot of things. Sternberg confided to Shinnick at one point:

“After trampoline practice one day last summer I decided to dive off the Montlake Bridge into the Canal between Lake Washington and Lake Union.”

“You wore your sweat outfit?” Shinnick asked.

“No I just wore some gymnastic trunks and a tank top,” Sternberg said. “I did a triple somersault with a double twist and made it.”

“Where did you dive from?”

“I just jumped up on the side rail, balanced, and then dove off. I had to do it fast so no one would think I was going to commit suicide or stop me. I hit it perfect.”

Shinnick threw a dirt clod at a tree as he digested that.

“My life has been perfect,” Sternberg continued. “I have a (new) girl friend who loves me, and now I have the world record. How could this get better?”

It couldn’t and it didn’t, for either of the Washington sophomores.

(This is the first of two Wayback Machine articles on two of the most remarkable athletes in University of Washington history, pole vaulter Brian Sternberg and long jumper Phil Shinnick)

————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

2 Comments

Thanks for such an enlightening story, Dave and Steve, one that many younger readers are first being exposed to. Lots of great details were provided, some familiar, but many that were new or I’d forgotten. As a young teenager my dad took me to a ton of UW track meets in those years (many held in weather every bit as cold/windy/rainy as a November Husky football game). So, Sternberg, Shinnick, their teammates and competitors were real giants in my mind. I clearly remember calling the “P.I. Sports Desk” late on a Saturday afternoon that spring of 1963 to find out how Sternberg did at an out-of-town track meet. And the person who answered the call was so courteous, patient and forthcoming — I guess that’s how we sports fans got instant information in those days.

It really is mind-boggling that Shinnick’s accomplishment(s) that day didn’t qualify him for at least a spot among the top ten local sporting achievements. But, as you indicated, track and field only appears on the radars of most people during Olympic years.

Your are welcome. Thanks for commenting!