In the late-afternoon swelter of July 29, 2001, minor-league baseball player Gerik Baxter and Mark Hilde, an unsigned recent draft pick who knew Baxter from their days at Edmonds-Woodway High School, climbed into Baxter’s Ford F-350 pickup truck near Phoenix and headed west.

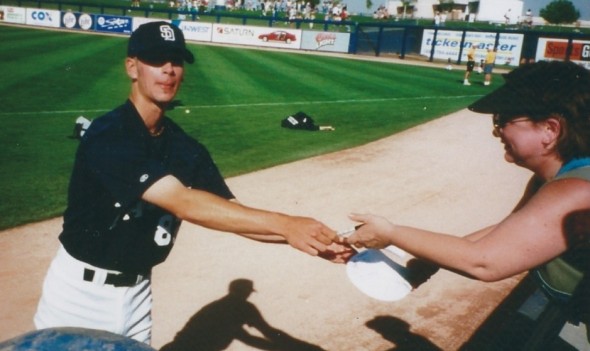

Baxter, 21, was recovering from May surgery on his pitching arm. He traveled from his minor league assignment in Lake Elsinore, Calif., to the San Diego Padres’ Peoria, AZ., spring training complex to watch Hilde play in a Connie Mack baseball tournament. Hilde’s team had been eliminated, so after stopping by a pool party at the home of Hilde’s uncle, the longtime friends decided to go to San Diego.

Temperatures were in triple digits. Baxter and Hilde were on their way, staring at the desert as afternoon turned to evening.

http://www.interstate-guide.com/i-010.html

Interstate 10 stretches 2,460 miles, beginning in Jacksonville, FL., 30 miles west of the Atlantic Ocean, through eight southern states to the heart of Santa Monica CA., just a mile or two from the Pacific Ocean. It’s hard to imagine a more deserted stretch than the 262 miles from Phoenix to Palm Springs. The four-lane road includes a border stop in Blythe, CA., where travelers gas up and grab a snack before driving through an expansive stretch of sagebrush that borders Joshua Tree National Park.

Baxter and Hilde became so close over the years that they were almost like brothers. They came from close-knit families, each with a younger sibling and married parents who filled with pride at the young men they had become.

Anyone who knew Baxter and Hilde had to assume they had country music on the stereo and wads of chewing tobacco in their lower lips. The kids from the close-in Seattle suburb took pride in their cowboy persona. Driving fast was one of their passions.

Police reports estimate Baxter’s truck was traveling at 75 to 85 mph as it approached the outskirts of Palm Springs around 7:30 p.m. Neither driver nor passenger was wearing a seatbelt.

Just outside the town of Indio, the tire blew. The pickup truck veered into another lane, taking out a Chevy Tahoe and flipping several times before landing in a ditch.

The driver and passenger in the Tahoe survived.

Baxter and Hilde did not.

In a flash, the 21-year-old pitcher who ranked fifth among prospects in the Padres organization, and the 18-year-old third baseman who had been drafted by the Oakland Athletics eight weeks earlier, were gone.

Impact, however, did not end there.

Impact

The sound of tragedy is often less chilling than the quiet that follows.

Smoke billowing from a highway wreckage.

The sun falling in the evening sky.

The time between rings of a telephone 1,270 miles away. Or the wordless gasping for breath that follows on the other end of the line.

For Sean McCormick, the silence was broken by the cracking voice of a longtime friend’s sister.

Words came hard.

They were dead. Baxter and Hilde.

“Within 20 minutes or so, there were 20 or 30 people at my house in Edmonds, in my front yard, wailing uncontrollably,” McCormick, a friend of Hilde’s since kindergarten, recalled recently. “There were several people who were just inconsolable. It was a shock.

The news quickly reverberated around Edmonds, sending waves up and down the spines of everyone the young men touched. By the next day, the baseball field at Edmonds-Woodway filled with mourners, uncertain of where to take their sorrow and how to process it. Friends and strangers wrapped their arms around each other in grief. Some left flowers. Many left a piece of themselves that they would never get back.

“Everybody was just kind of in shock,” longtime friend Nicole Bordeaux said last summer, 11 years later. “It was the first tragedy that had happened from our high school. They were huge in the community. Everybody knew of them and what was going on in their lives.”

Not just the E-W student body was affected.

“They were such neat guys that they had a big impact on a lot of us adults here at the school,” said Angie McGuire, who taught Baxter and Hilde in English class and now serves as athletic director at E-W.

Longtime Hilde family friend Carolyn Nacke found out Monday morning, shortly after the car of E-W junior varsity baseball coach Brett Warner pulled into her driveway while she watched from the kitchen.

“It was really hard to take,” said Nacke, the family friend who worked security at E-W High. “They were not only excellent baseball players, but they were really good, decent human beings.”

The impact of that day would not be forgotten.

The impact that Baxter and Hilde had on the lives of friends and loved ones would only grow over the years.

Aroma of cut grass

What would have been Mark Hilde’s 30th birthday came and went on New Year’s Eve. Gerik Baxter’s San Diego Padres won the NL West in 2005 and 2006, with Jake Peavy at the front of the pitching staff. The former Edmonds-Woodway star wasn’t around for the ride.

All these years later, it’s still difficult.

“It’s hard to explain,” Bordeaux said last summer. “Regardless that it’s been 11 years, you still have moments when you’re still angry, when you’re still sad, when you’re like: Did that really happen?

“It’s still hard to swallow.”

Bordeaux doesn’t think about baseball when her mind wanders back to that summer after her senior year of high school. The Edmonds-Woodway High School volleyball coach doesn’t wonder where Peavy and Hilde would be in their careers right now as much as she thinks about where they would be in life.

“I know they would’ve had families, had kids,” Bordeaux said. “Gerik would’ve been a great dad; he was really close with his niece. They both would have been really great fathers.

“For lack of a better word, it sucks that you don’t get to see that part of their life. You don’t get to see them as fathers, as husbands and family men. Obviously, we just hold on to the memories.”

As quickly as the memories bring a smile, the truth brings tears.

“It’s still very difficult to talk about without getting really emotional,” said McGuire. “Both of those guys were just such exceptional human beings that it’s still hard to think about that they’re not here.”

Several former classmates, inspired by the love of body art Baxter developed in his final months, have tattoos to help honor their friends. Sean McCormick was one of several members of E-W’s class of 2001 who have tattoos of crossed baseball bats, along with No. 12 — Hilde’s jersey number.

Eleven years later, McCormick gets a pang whenever he smells fresh-cut grass; it brings back memories of how Hilde used to spend hours keeping the lawns of his grandfather’s property immaculate.

Whenever McCormick thinks back on the worst day of his life, he struggles.

“The thought of unfulfilled promise and the notion that the best people aren’t necessarily guaranteed to live a long time,” he said when asked what remains from the loss.

At a memorial service held at Edmonds-Woodway before the start of the 2001-02 school year, number touched by the accident was apparent.

“We have a staff of a hundred-something, and everybody was there,” family friend Nacke recalled last summer. “We have over 1,000-something kids, and it was standing-room-only outside.”

The service included a slide show of Hilde and Baxter. Nacke wells up when she hears the song played in the background — a country song, of course, by Lee Ann Womack: “I Hope You Dance.”

“Time is a wheel in constant motion rolling us along / Tell me who wants to look back on their years and wonder where those years have gone.”

Those left behind try not to waste the time, yet it’s hard not to get lost in the past.

“As time goes on, I don’t think people forget, but it becomes further and further away,” Bordeaux said. “For me, I feel like they become closer and closer. All these important moments in life that you get to enjoy — your first job, people getting married, having kids — and they’re not here to experience it.

“They had such a huge impact on all of us. It’s right there. You can feel it even more.”

Baxter and Jake Peavy

Almost 12 years have passed, and still Barry Axelrod stares into the eyes of Gerik Baxter almost every single day.

In his office, the longtime sports agent has a photograph Baxter gave him long ago, serving as a constant reminder of the up-and-coming baseball star whose life halted on a California highway.

“It’s hard,” Axelrod said in December. “He would’ve been 31, 32 now. You think about what might have been. Watching Jake Peavy and what he’s been able to do has been a constant reminder of what could have been for Gerik.”

Axelrod, who once represented both pitchers, can’t help comparing Baxter to Peavy because they were so similar on so many levels. Both carried a confidence that often disguised their quiet, respectful natures. They came into baseball at the same time and were always aware of the other. Both were destined for stardom.

Peavy rose to Double A by the end of the 2001 season, earning a chance to play in his hometown of Mobile, AL. By the middle of the next season, at 21, he received the call every player desires.

On June 22, 2002, less than 11 months after Baxter’s death, Peavy was at Yankee Stadium making his major league debut for the San Diego Padres. He allowed just one run on three hits over six innings, then became a mainstay in the Padres rotation for seven-plus seasons. Peavy would win the 2007 Cy Young Award that annually goes to best pitcher in each league, and he would appear in four All-Star games — his most recent one last year, as a member of the Chicago White Sox, to whom he was traded in August 2009.

Peavy recently signed a two-year, $29 million extension with the White Sox that, tacked on to what he earned as a Padre — his three-year, $52 million contract in 2007 marked the largest in club history — make for about $114 million in earnings since the 2007 season.

Could any of that have happened to Gerik Baxter?

“I never think about what could have been, because I know he would have been in the big leagues,” said Travis Devine, a former teammate of Baxter in the minors. “He would have succeeded, no matter what.”

Before Baxter’s star could shine, the stage went dark.

One dream continues

Jake Peavy is a man now, his face weathered and his piercing, blue eyes having lost some of the sparkle.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/peavyja01.shtml

He stands in the visiting clubhouse at Safeco Field, a 13-year veteran and an unquestioned leader of the White Sox. Soon as he hears the name, his face tightens.

Gerik Baxter.

“He had an unbelievably gifted right arm,” Peavy says, eyes glassing. “I can go back in my mind and still see him throwing a bullpen (session). His arm was outstanding.”

Peavy also remembers the rivalry, one that made both better.

“It was a good friendship,” he said, “but there was no doubt that we were trying to one-up each other.”

Peavy has done plenty during his 13 years as a major league pitcher. One name brings him back to that summer in 2001.

Peavy was 20 when Gerik Baxter died.

“Of course it did,” Peavy said when asked if Baxter’s death impacted his own life. “He was somebody who had everything that you could ever want at that point in your life. He was a popular guy in high school, comes out and gets drafted in the first round, he’s been given some financial security in life with the money, he was progressing through the system. And then to have that taken away in the blink of an eye, when nobody could have expected it, that was certainly a life-changing thing for somebody my age.

“It wasn’t long after that when 9/11 changed the world. Some big things happened that year that makes you think: Gosh, live each day to the fullest.”

Peavy fulfilled his major-league dream by seeing how far talent could take him. Baxter did not. All Peavy can do is wonder.

“The sky’s the limit as far as what he could have been,” Peavy said. “To sit here and have to have this conversation shows that the world’s a crazy place; there’s no promise of tomorrow.”

Bad gives way to good

No one can know. Really, would you want to?

Would you want to know what it feels like to have a child taken away from you before his time?

To be there for that first breath. The first step. The first words. The first time a child throws a ball, to see the excitement, to watch as he spends a young life trying to perfect the craft. To watch him grow from a frightened child to a young man filled with confidence and awareness and real dreams.

Then to lose him, on the cusp of adulthood, before he can go out on his own and become the person he always dreamed of.

No one can pretend to know what that’s like.

Doug Kirton, an Everett man who lost his son, Johnie, when the former Jackson High and University of Washington football star was 26 last spring, recently told a story about how well-wisher after well-wisher attempted to comfort him with words of understanding. The words sounded hollow to his ears, and sometimes it even made him angry.

No one, Doug Kirton said last year, could ever truly understand.

So how does one describe what it’s been like for Brad Baxter and Darrel Hilde? They didn’t lose up-and-coming baseball prospects; they lost the most meaningful thing in their lives.

This is what Brad Baxter said about July 29, 2001: “We just stopped everything. You don’t have any choice. It just stops you.”

It would be vapid to say that the Baxter family has moved on. They have moved along. Some days are better than others. Some times of year are hardest. Brad and his wife, Betty, escaped most of the constant reminders by moving to Shelton, but now live on a dual property that includes a plot of land once purchased by Gerik with dreams of one day building a house.

“There’s always Christmas and birthdays,” Brad Baxter said via telephone recently. “The day of the accident is always really weird. Betty and I just kind of disappear. We just go away. It’s still real sensitive.”

Anyone who has children, even adult children, must look at Brad and Betty Baxter and ask themselves the same thing.

How on earth can they go on?

The Baxters find some kind of solace in faith.

“We both know what’s going on,” Brad Baxter said. “There’s a real serious part to this that’s kept us together. Betty and I are followers of Jesus. Gerik wasn’t the perfect guy — he’d do beer-drinking with his buddies and stuff like that — but he was a believer.

“Sometimes, we’ll get away from the action and maybe just watch a baseball game or something, and think about what’s going to happen eventually, and try not to spend a lot of time on the woulda-coulda-shoulda. For us, it’s not about focusing on the loss; it’s just something we’re anticipating down the road.”

Darrel and Terry Hilde can understand; they wish they couldn’t, but they can.

They too lost something precious that day, something precious that day, something that can never be replaced.

There were days when Darrel Hilde would drive to work, only to find himself so overcome that he turned around and called in sick. Other days, he didn’t know if he could go on.

“I was numb for four or five years,” he said recently. “I didn’t want to deal with anything. But then over time, the bad memories went away, and the good memories come in.”

One memory that he still can’t fully grasp comes from that sweltering July day 12 years ago.

“I can’t describe it,” Hilde said of hearing the news while the family was vacationing in Arizona. “It was like shock. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. We were up all night. It was a nightmare.

“It was a feeling of loss I’ve never felt. I never felt angry. It’s really hard to describe.”

The family will never be truly at peace. But Darrel said he no longer shields himself from the memories.

I enjoy talking about it,” he said. “It used to hurt really bad, but it doesn’t hurt anymore.”

There comes a tim when one simply can’t think about death anymore; no more energy to think about what could be. The energy goes toward good things.

Dealing

In the days before Christmas, rain left muddy the basepaths at Edmonds-Woodway High School. Gone were the numbers that spent a few years posted on the fence along each baseline: Hilde’s No. 12 near third base, and Baxter’s No. 7 by first base.

There is no evidence of Hilde and Baxter at the high school field, other than a small sign behind home plate that thanks a dozen or so contributors for donations to the field — Baxter among them.

Joe Webster doesn’t roam the ballfield, either. The Warriors’ former coach is removed from the school, having left in 2006 after establishing an annual Baxter/Hilde scholarship there (in the amount of $712, a nod toward the players’ jersey numbers) before taking over as principal at Meadowdale Middle School.

http://www.ewhsbaseball.com/view/ewhsbaseball/home-page-275/hilde-baxter-scholarship-fund

Webster, father of three, is not around the E-W program anymore. He certainly hasn’t forgotten Baxter and Hilde. He thinks about them often.

“Every day,” their former high school baseball coach said. “It’s kind of weird: I don’t really watch major league baseball much. I’m still a fan, I still coach, but I just can’t do it. I’ll end up watching it and see guys Gerik was in the minors with, guys like Jake Peavy. You get that what-if feeling. And Mark was drafted by A’s, so every time the Mariners play the A’s, it’s just like . . . yeccch.

“That was a traumatic time. It seemed like the whole community at E-W was really affected by that. And it went on for weeks.”

It still goes on. An empty baseball field tells a small part of the story. This is a tale about baseball, but it’s about a lot more.

It’s about impact.

News of the July 2001 accident came and went on the sports pages, but for many in the Edmonds community, it will never go away.

“Did life change? Absolutely,” said Bordeaux, a longtime friend of both men. “It makes you appreciate your friendships that much more.

“You never expect that a person that close to you will be gone suddenly. You can never prepare for it. It makes you learn to enjoy life more.”

Sean McCormick, who first became friends with Hilde in kindergarten, likes to think that his longtime buddy has more of an impact to make.

“His life was snagged early, but I think that he did his part to make people feel good,” McCormick said. “I believe in reincarnation, that the human soul is infinite, and his incarnation in this life was spent well. The next time he comes back, maybe he’ll get a little bit longer. Maybe he’ll get an opportunity to do even more and to affect even more people positively.”

Former minor-league pitcher Travis Devine also looks back at that tragic day in 2001 with a sense of hope.

“It just made me learn to appreciate life,” Baxter’s former teammate said. “There’s life, there’s family, and baseball is No. 3. It could be your last day of taking a breath, and you don’t want to waste it.”

The impact of two former Edmonds-Woodway students and teammates is still there, even if the 95 mph fastball, and Hilde’s contagious zest for life, are gone.

“They were awesome kids,” Darrel Hilde said, “and they were loved by a lot of people.”

For information on the Hilde/Baxter Scholarship Fund, go here.

1 Comment

Wow, great writing and a very touching story. Reading this made me think a lot about life and the many twists and turns that go into making a life of substance and meaning. Once again, I am reminded to not take things for granted and to value each day.

Thank you.