By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

Jack Wayne Lohrke did not have a distinguished major league career. He spent seven seasons in the National League between 1947-53, mostly as a utility third baseman, shortstop and second baseman with the New York Giants and Philadelphia Phillies. But Lohrke, a Los Angeles native, was fortunate to have had a career at all, after escaping death at least six times during World War II.

As a member of the U.S. Army’s 35th Infantry Division, Lohrke fought in the D-Day invasion of Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge. On four occasions, solders on both sides of him were killed in combat while he emerged unscathed. Another time, Lohrke survived a troop train crash that killed three and injured dozens more.

En route home from the war in 1945, Lohrke was bumped at the last moment from a military transport plane scheduled to fly from Camp Kilmer, NJ., to his home in Los Angeles via a military installation in San Pedro.

“They bumped me to make room for some big-shot,” Lohrke told The New York Times in 1990. “I was miffed.”

The plane crashed 45 minutes later, killing all aboard.

By the time Lohrke, playing third and batting eighth, made his major league debut April 18, 1947 in a 10-4 victory over Jackie Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers at the Polo Grounds, he already sported the nickname “Lucky.” But the moniker had little to do with brushes with the beyond he’d experienced as a soldier.

Upon his honorable discharge, Lohrke received the American Campaign Medal, the European African Middle Eastern Campaign Medal and the Victory Medal for his wartime service, then resumed his baseball career, which began in the early 1940s when he was discovered by San Diego Padres scouts on the semipro sandlots of Los Angeles.

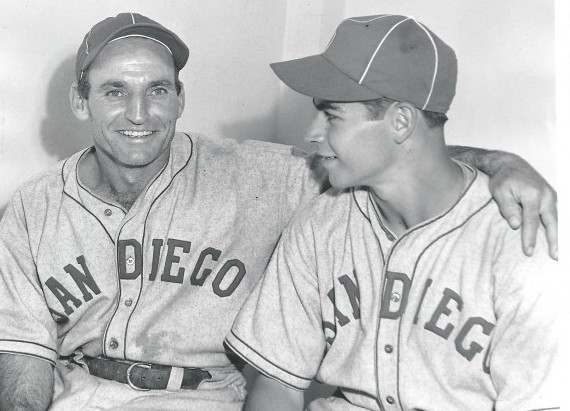

Born Feb. 25, 1924, the second of three sons of John and Marguerite Lohrke, Jack Lohrke graduated from South Gate High School in 1942. That year, the AA San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League signed Lohrke to his first pro contract and gave him a seven-game audition – he went 2-for-17 (.118) – before shipping him to the Class C Twin Falls Cowboys of the Pioneer League.

Lohrke played 105 games and hit .271 (he was named the team’s Most Valuable Player) before World War II beckoned, placing his career on hiatus for four years. When he rejoined the Padres, they assigned him to the Class B Spokane Indians, a Western International League entry that also had an affiliation with the Oakland Oaks.

Despite four years away from the game, Lohrke got off to a fast start. In 57 games, he hit .345 and found himself the Western International League’s leading batter after games of June 23, 1946. That day, he had four hits, including a home run, as Spokane split a day-night doubleheader with the Salem Senators at Ferris Field.

The next morning, a Monday, at approximately 10 a.m. under drizzly skies, the Indians boarded a chartered Washington Motor Coach for a 292-mile, cross-state trip to Bremerton. The hometown Bluejackets stood a game back of first-place Salem in the WINT standings, and the seven-game series would take the Indians to the halfway point of the season.

Mel Cole, Spokane’s 25-year-old catcher-manager, assigned seats for the trip: Pitchers George Lyden, 22, and Gus Halbourg, 26, sat alone up front on either side of the aisle. Cole seated himself behind Lyden in the second row, opposite the aisle from 24-year-old outfielder Bob James.

Lohrke drew the window seat on the left side of the third row, next to “The Chief,” veteran outfielder Levi McCormack, who had broken into professional baseball with the Seattle Indians in 1936. Second baseman Fred Martinez, 24, and pitcher Bob Kinnaman, 27, sat across the aisle from McCormack.

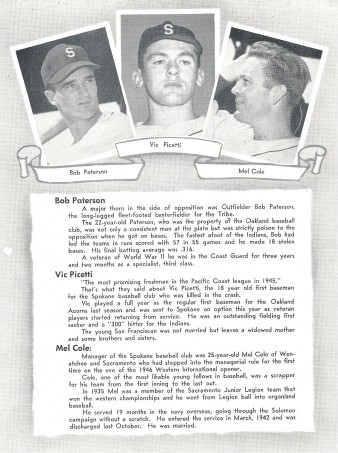

Eighteen-year-old Vic Picetti, a promising first baseman, sat behind Lohrke, and outfielder Bob Patterson, 22, sat next to him. Shortstop George Risk, 25, catcher Chris Hartje, 30, infielder Ben Garaghty, 33, pitcher Dick Powers, 29, and catcher Irv Konopka, a former University of Idaho football player, occupied the back seats. Pete Barisoff, a pitcher, settled on the wide rear seat. Driver Glenn Berg counted heads.

Two Indians players did not get on the bus, traveling separately in their own vehicles. Spokane’s trainer, John “Dutch” Anderson, also did not travel with the team, in San Francisco attending to personal business.

Lohrke was surprised to find himself on the coach. He’d heard – nothing official – that he was about to be promoted to San Diego and thought the summons would come, if it came at all, before the Indians departed for Bremerton. But since he hadn’t heard a thing, he sat in his third-row window seat as Berg closed the doors and the Washington Motor Coach pulled out of the Ferris Stadium parking lot.

Although the Indians were in fifth place after 60 games, they were only a handful of games behind Salem and had the makings of a good ball club. In addition to Lohrke, they had four regulars – Picetti, McCormack, Patterson and Martinez — batting better than .300. Lohrke, Paterson (.317, 15 stolen bases) and Martinez were all considered major league prospects. Picetti, the latest in a line of San Francisco Italian-American ballplayers that included Vince, Joe and Dom DiMaggio, Frankie Crosetti and Dolf Camilli, was viewed as “can’t miss.”

At about the time that the bus stopped in Ritzville for gas, team owner Sam W. Collins, in Spokane, received a telegram from the San Diego Padres informing him they wanted Lohrke to make the jump from Class B to AAA — and that they wanted Lohrke to report immediately.

Collins tasked team business manager Dwight Aden with locating Lohrke. But after Aden discovered that long-distance telephone lines were out of service in the center of the state, he prevailed on the Washington State Patrol to contact police in Ellensburg, 175 miles west of Spokane. While bus driver Berg took the Washington Motor Coach to a garage for quick repairs, police located Lohrke in a restaurant, downing hamburgers with his teammates.

They advised Lohrke of his promotion and passed along Aden’s order that he return to Spokane immediately. After lunch, when the Indians reboarded, Lohrke also climbed aboard to shake hands with his teammates and say goodbye.

Lohrke never saw any of them again.

“When the bus took off . . . I hitched a ride back to Spokane,” Lohrke told the Los Angeles Times in 1990. “I didn’t hear what happened until I got back to Spokane.”

In those days, U.S. 10 was a two-lane route that carried traffic up and over Snoqualmie Pass, 57 miles west of Ellensburg and 50 miles east of Seattle. Dusk approached and rain fell steadily as the bus chugged toward the summit. At one point, according to Sports Illustrated, Hallbourg looked out his window and saw only darkness below. But he could hear the south fork of the Snoqualmie River raging in the abyss.

“Wouldn’t this be a hell of a place to go off the road?” Hallbourg asked teammate Kinnaman.

At about 8 p.m., the coach crossed Snoqualmie summit. Four miles down a slope of U.S. 10 that clung to the south side of the ravine, Berg noticed an eastbound black sedan cross over the center line, headed straight for the bus. Berg told investigators that he swerved toward the right shoulder, but that the sedan sideswiped the front corner of his vehicle. That caused the bus to veer off the pavement and skid along the wet roadway. While Berg struggled to maintain control, the bus took out 125 feet of guardrail before careening over the edge.

It tumbled down the incline, striking a large boulder and rolling onto its left side. It hit another boulder and rolled twice more, pitching some of the players and their gear through shattered windows. After falling an estimated 350 feet, the bus burst into flames and settled, right side up, astride a log, where it burned to its frame.

The June 25, 1946 edition of The Seattle Post Intelligencer described the scene as “a raging holocaust.”

With the aid of emergency flares and spotlights, rescue squads roped down to the bottom of the ravine. There they found six Indians — players Fred Martinez, Bob James, Bob Kinnaman, Bob Paterson and George Risk, along with catcher-manager Mel Cole, already dead. First baseman Vic Picetti died later that night, soon after arriving at King County Hospital in Seattle. Pitcher George Lyden died from his injuries the following day, and catcher Chris Hartje, who had been seriously burned, died two days after that.

Nine dead, all but Picetti a World War II veteran. It was – and remains – the deadliest crash involving an American pro baseball team

The six survivors (not counting Berg, the driver, who lived) suffered serious injuries, some requiring months of hospitalization. Only a few played baseball again, and those not for long.

When the hitchhiking Lohrke, who would have been sitting across the aisle from Martinez and Kinnaman (both of whom died at the scene) when the bus tumbled off U.S. 10, arrived in Spokane, he called Collins and asked when he was supposed to report to San Diego.

Collins told Lohrke about the accident, and Lohrke immediately wired his parents in Los Angeles, informing them he was safe. John and Marguerite Lohrke had not yet heard about the accident, but very soon it became news across America and brought a major response.

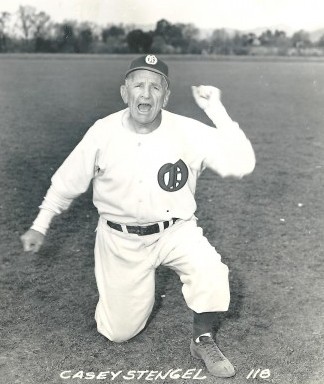

Donations poured in from fans and other baseball teams across the country. The Pacific Coast League joined with the Western International League for a benefit game to raise money for the Spokane players. Manager Casey Stengel and his Oakland Oaks, who had lost farmhands Picetti, Paterson and Kinnaman, played a memorial benefit game at Ferris Field against the Seattle Rainiers July 8. They paid their own expenses to play.

The game raised $24,257, thanks in part to Bing Crosby, an alumnus of Gonzaga University in Spokane, who bought $2,500 worth of tickets to give to servicemen and also donated another $1,000.

Dixie Walker, the Brooklyn Dodgers outfielder, suggested that Spokane receive a slice of All-Star Game income and Commissioner Happy Chandler sent a $25,000 check. Ultimately, a fund reached $114,805.25. It was shared on the basis of injuries, number of dependents and probable length of recovery. Pitcher Powell, his neck broken and in the hospital months later, got the most, $11,919.10.

Other teams lent players to the Indians, and the team returned to its schedule July 4, finishing out the season with a ragtag roster. Three of the six survivors returned, the others never played again.

After arriving in San Diego, Lohrke hit .303 as its regular shortstop in the 92 games remaining on the Padres’ 1946 PCL schedule. The New York Giants drafted Lohrke in early 1947 and he spent much of that season as their third baseman, hitting .240 with 11 home runs in 112 games.

Lohrke did not develop in the majors into the hitter he had been in the Pacific Coast League, finishing with a .242 career average in 914 at-bats with 22 home runs for the Giants and Phillies. His best season was 1949 when he hit .267. But he managed a .310 average (13-for-42) off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn and batted .458 (11-for-24) against Johnny Vander Meer, architect of consecutive no-hitters.

Lohrke never made any baseball history, but he saw it: He was warming up outside the Giants’ dugout as a possible replacement at third base when Bobby Thomson hit “the shot heard round the world,” which won the 1951 pennant.

His major league career over, Lohrke returned to the PCL in 1954, spending two seasons with the Hollywood Stars, two more with the Seattle Rainiers (1956-57) and a season each with Portland and Tri City of the Northwest League. Lohrke hit .272 in 49 games under Rainiers managers Luke Sewell and Bill Brenner in 1956 but only .143 under Lefty O’Doul in 1957.

From the moment Lohrke joined the Padres after the bus accident, he was called Lucky — the soldier unceremoniously bumped from the plane that crashed, the soldier who watched other soldiers die all around him, the ballplayer who got off the bus just in the nick of time. Although Lohrke didn’t like it, preferring to be called Jack, the Lucky moniker stuck, and he’s listed in the Baseball Encyclopedia that way: Lucky Lohrke.

Following his retirement after the 1959 season, Lohrke went to work as a security officer for Aerojet General in Sacramento. He later worked at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory (1968-71) and concluded his days in security with a 15-year stint at Lockheed. A San Jose resident for 40 years, Lohrke retired in 1986 and died April 29, 2009, two days after suffering a stroke.

Lohrke never talked much about June 24, 1946, but on those occasions that he did, he maintained that war had conditioned him to deal with disaster.

“Having been in combat, what’s going to shock you?” Lohrke told Sports Illustrated in 1990. “I’m a fatalist. I believe the old song, that whatever will be, will be.”

The black sedan that sideswiped the bus four miles west of Snoqualmie Pass was never found. Police and the Washington State Patrol searched for it and thought they had a lead when a Vantage, WA., service station operator reported that a driver had boasted to him that he had forced a bus off the highway. The authorities checked out the service station operator’s story, but nothing came of it.

——————————————-

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com