By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

In its afternoon edition of May 15, 1955, The Seattle Times printed a headline on the first page of its sports section that blared, “Colleges Drool As Tacoma Ace Adds Track Laurels.” Sans byline, the story reported without equivocation, “Luther (Hit and Run) Carr, Lincoln High’s greatest athlete, is the biggest sensation in Tacoma since the collapse of the Narrows Bridge.”

Since Galloping Gertie famously blew down Nov. 7, 1940, that made Luther Carr Tacoma’s biggest sensation in 15 years. Given his athletic feats, then and later, it is easy to see why.

The Times further noted that Carr, first-team All-State in football (20 touchdowns as a senior) and baseball, a starter on Lincoln’s basketball team, and a .399-hitting outfielder for the Cheney Studs, one of the best amateur baseball clubs in the U.S., hadn’t yet made known his college preference, but speculated he narrowed his choices UCLA, Illinois and Washington. Then The Times recounted a recent Carr feat.

On a “lark,” a word Carr later used to describe his participation, he accompanied the Lincoln High track and field team, of which he was not officially a member due to his commitment to baseball, to the Clover Park Invitational where he entered the long jump – broad jump in those days – plus the 100 and 200 races.

Carr easily won the sprints. On his first attempt in the long jump, he soared 24 feet, six inches, nearly a foot and a half better than the state prep record set in 1938 and three inches shy of the national prep mark. But he scratched by a quarter of an inch. Then he jumped a legal 23 feet, 9¾ inches, a meet record and nearly a foot beyond the state mark.

Carr grew up in Tacoma’s less-than-posh Salishan housing project and rarely had an opportunity to escape his surroundings. So when the chance presented itself to travel with the Lincoln track team to Pullman, WA., for the state championship meet, he jumped at it – and promptly jumped into the record books.

Relying on raw talent, and without any practice jumps, Carr had an early mark of 23-2½ and then exceeded that – and the state mark – with a jump of 23-7. Carr also ran the leadoff leg for Lincoln’s winning 800 relay team and finished second in the 100, clocking 9.9 seconds.

The same day Carr established the prep long jump record, the University of Idaho’s Wilbur Gary won the event at the Pacific Coast Conference championships in Eugene, OR., with a mark of 23-1, and Gordon Fee of Seattle Pacific took the same event at an NAIA regional meet at Renton Stadium with a leap of 21-9 ½. Carr’s 23-7 would have qualified him for the 1956 U.S. Olympic trials.

“I was a multi-person person in football, basketball, baseball and track, but track was really never part of my repertoire,” said Carr in May, 2013, when he was contacted to provide reminiscences on the 60th anniversary of the Cheney Studs. “It was an afterthought. My parents had nine kids, I was the oldest and I had to take care of them, and I would do anything to get out of the house. I liked going to Pullman, and it gave me a trip. It was a lark.

“I held the state record for a number of years, but wasn’t really a track man. But I could run and I could jump and that allowed me to excel. I could have been an Olympian. I had the fourth or fifth best jump in the nation at the time, and it was a choice of trying out for the Olympics and training, or staying in school and playing baseball and football. Plus, I had a girlfriend (Frances, his future wife of 56 years) and she had me by my nose.”

By the spring of 1955, Carr had a variety of athletic options. Had he taken track and field seriously, he probably would have made the 1956 U.S. Olympic team. In fact, that 23-7 would have made the medal round at the Olympic Games in Melbourne. Although track didn’t interest him much, baseball certainly did.

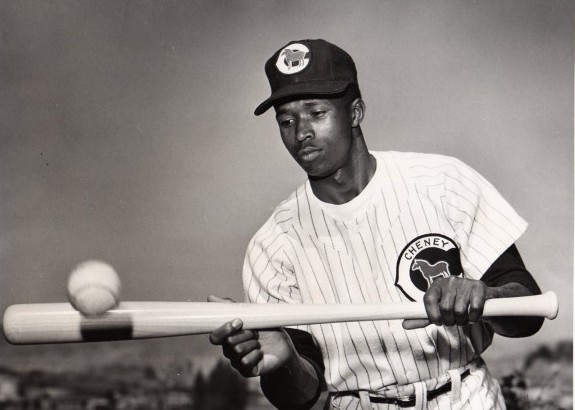

Carr was so good that in 1954, as a high school junior, he made his debut with the Cheney Studs and hit .399. Easily the best athlete on the team, Carr was Most Valuable Player in Cheney’s 9-4 victory over the Kirkland Athletics in the title game of the State Amateur Championships after hitting a solo home run, double and three singles in five trips to the plate.

From Lincoln High through his play with the Studs in the Northwest League, Carr never hit less than .300 and had the tools to become a major leaguer. But football was his passion and no end of suitors wooed him.

In those days, colleges had to pony up considerable cash in order to secure the services of talents such as Carr, and there was nothing illegal – yet — about it. UCLA, Illinois and Washington were among many schools willing to pay whatever it took – even more. The Bruins twice tempted Carr with lavish offers during his recruiting trips to Los Angeles and spiced his visits by introducing him to celebrities. One weekend, Joe E. Brown, then a famous comedian, served as his host.

Illinois reportedly offered $200 per month, but Carr settled for less, reportedly $175, to attend Washington. Even a competing offer from Branch Rickey to play baseball professionally failed to sway Carr from the Huskies. Carr’s major priority, instilled in him by his father, Luther Sr., was receiving an education.

Rickey, who broke the color barrier by signing Jackie Robinson, made a trip to Seattle during Carr’s freshman season and tried, during a negotiation in Seattle’s Franklin Hotel, to convince him to sign with the Pittsburgh Pirates, the club that employed Rickey as its general manager.

Rickey was smart and persuasive: He had not only signed Robinson, he signed Roberto Clemente, the first Afro-Hispanic superstar. He also created the framework for the modern minor league system, introduced the batting helmet, set up the first full-time spring training facility in Vero Beach, FL., and pioneered the use of what is now known as sabermetrics.

But Rickey couldn’t come up with enough money to lure Carr out of school. That was only part of the reason Carr turned him down.

“I didn’t want to play minor league baseball and run around the country and miss out on getting a good education,” said Carr, who had another priority: The Rose Bowl.

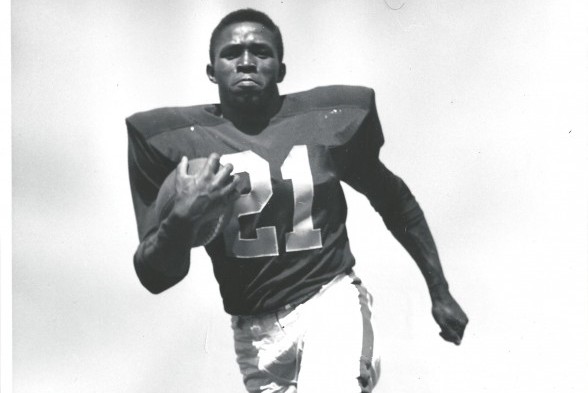

Carr played with the Washington Pups in 1955 – he produced a highlight-reel 94-yard touchdown against Idaho — and moved to the varsity in 1956, becoming an instant sensation. In his varsity debut, also against Idaho, he ran for 99 yards, including a 24-yard touchdown in the second quarter. He had a 27-yard TD run against Oregon.

“The boy is a 185-pound hydrogen bomb,” wrote Times columnist Georg N. Meyers.

Carr rushed for 101 yards on six carries against California, scoring on a 74-yard run on his first carry. He snagged a 38-yard TD pass from quarterback Al Ferguson against Stanford. He led the Huskies in rushing with 476 yards, but averaged only seven carries per game mostly because . . . well, because most of the time he sat and watched.

Washington didn’t do black athletes in those days. Or, it did them uncomfortably and as infrequently as possible. Carr had the talent to produce Napoleon Kaufman numbers, but finished a 30-game career – only seven starts – with 841 rushing yards and eight TDs. It says a lot about Carr’s abilities as an athlete that he made honorable mention All-Pacific Coast Conference with so little playing time.

“Every time we lost,” said Carr, “I got demoted to third string.”

The son of a factory worker, Carr conceded that he got “gypped” during his time with the Huskies, although he evidenced no hint of bitterness or regret that head coach Jim Owens, who replaced Royal in 1957, in those days packed a huge racial bias, and that he treated white athletes far better than black ones.

“I had three different coaches, Cherberg, Royal and Jim Owens,” said Carr. “They are all dead now. Of course, I’m almost dead too. Owens didn’t know how to handle his black ballplayers. That guy wouldn’t give me a break, but that’s the way it goes. Of course, I was annoyed because I planned to be a good player. But every time we lost I went from the first team to the third team. There wasn’t anything I could do about it. I wasn’t going to change the world.

“The reason I stayed the course was that my dad was a big advocate of education and he said, ‘It’s rough out here and you better get an education.’ For me, it was an easy decision to stay and I’m glad I did it. It was the best thing that could have happened. Even though Owens wasn’t fair, I decided I was going to stay and be a man. That was my first serious confrontation with reality. Plus, there were a lot of good guys on the team.”

Carr never would have connected with Tacoma, UW or Owens if not for World War II. Born in Atlanta May 17, 1936 as the Great Depression raged, he came west with his father, Luther Carr Sr.

“It was 1941 and Pearl Harbor had just happened,” said Carr. “An aluminum plant was gearing up (in Tacoma) and this man came around and he says, ‘Boys, you got two alternatives. You can go to the army or you can go west to Tacoma.’ So my dad chose Tacoma. That’s where I grew up and went to elementary, junior high and high school.”

Despite his infrequent starts for the Huskies, the San Francisco 49ers were sufficiently impressed with his speed and athleticism that they selected Carr in the 21st round of the 1959 NFL draft, 246th overall, the equivalent of a seventh-round draft choice today.

It was nearly a throwaway pick since no rookie was going to crack the 49ers’ backfield. San Francisco had two future Hall of Famers, former Washington star Hugh McElhenny and Joe “The Jet” Perry, and neither was San Francisco’s best back that season, that distinction belonging to J.D. Smith, younger than both McElhenny and Perry, and a Pro Bowler.

A year later, Carr earned a roster spot with the Oakland Raiders of the newly created American Football League. One preseason punt return changed everything.

“I went down the field on a punt, got ready to nail the ball carrier and somebody nailed me,” said Carr. “I found myself flying through the air, I hit the ground and couldn’t get up. I had to get an operation on my spine. The doctor told me I might never walk again, but fortunately I recovered. But after that it (sports) was over for me.”

Following his 1958 UW graduation, Carr watched the Huskies, with George Fleming playing his position, go 9-1-0 and earn a Rose Bowl berth opposite Wisconsin, a team they obliterated 44-8. During Carr’s three varsity seasons, UW went 11-18-1.

“The one regret is that I didn’t get to the Rose Bowl,” said Carr. “I never had a chance to enjoy that and I would have been nice. I missed it by one year.”

Shortly after the Huskies dismantled Wisconsin, Carr stood next to Fleming at a Husky basketball game and discovered how fleeting fame can be.

“A kid came up and asked George, ‘Could I have your autograph?’ He was a teenager, and George said, ‘Don’t you also want this guy’s autograph?’ The kid looked at me and George said, ‘This is Luther Carr,’ and the kid said ‘I don’t know who he is,’ and turned around and walked away.”

Carr did not want to talk about what kind of runner – or athlete – that he used to be, or compare himself to anyone who followed him, except to say, “George and I were close to being the same kind of runner. I was faster than George, but George could kick (one reason he was co-MVP of the 1960 Rose Bowl with Bob Schloredt).

“I would have liked to have been like Gale Sayers or Hugh McElhenny. Man, was he something. But now all that’s in the past. I played football for all it was worth and it gave me a lot of notoriety and benefited me immensely. A lot of people wanted to hear my B.S. and it allowed me to educate my kids.”

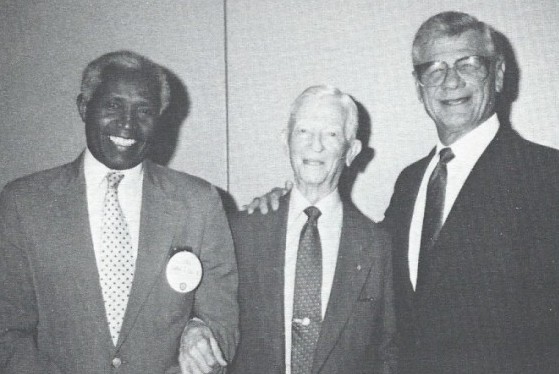

Heeding his father’s advice, Luther Carr received a good education and made the most of it. Among many accomplishments, he was the first black to gain membership to the Rainier Club and Washington Athletic Club. He also became a member of Seattle Rotary and served on many boards, including the Seattle Housing Authority.

“I came from a very poor circumstance to going to the Inaugural Ball for two U.S. presidents, Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter,” said Carr. “And I met so many great people. I’ve been president of United Way and on the board of the Chamber of Commerce. I was an independent businessman (Carr-owned Urban Construction Company was the largest minority-owned construction company in the state) for 40 years running my own company . . . construction, insurance, finance, and whatever else came along that made an honest buck.

“I’ve been married for 56 years (Frances) and, man, and I’ve had a wonderful life. But I don’t want to talk about the good old days, even though they were center of my life for so long. Notoriety I don’t need. Publicity I don’t need. I’m on the shady side of the hill now, so I enjoy what little life I have left.

“I’m 76 years old. It’s not 100, but I do yoga. That’s my big thing. I’ve gone from doing four athletic sports in a year to yoga. I’ve gone from moving a lot, to moving a lot in one space. I can’t even run across the street now.”

Not that any of it necessarily helped him personally, but Carr expressed gratitude that he bore witness to the emergence of Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King.

“I also saw a black man become president, which I never thought I’d see,” said Carr. “If I were to write my obit, I’d say, ‘He had a chance to compete.’”

As a successful businessman, community leader and civic activist, Luther Carr competed as well in his non-athletic life as he did in his athletic one, leaving behind an enviable legacy of success to a fine family, widow Frances, daughters Brenda Carr Nelson, 55 (Seattle), Dana Carr, 52 (West Seattle) and Luther Carr III, 43 (West Seattle, and also the head football coach at Chief Sealth High) when he passed away July 1 at 78.

————————————–

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or atseattlesportshistory@gmail.com

4 Comments

I wasn’t aware that Luther Carr had passed away. He was before my time and it sounds like he was ahead of his own. Nice writeup of a man who understood what went on around him and turned his life into a legacy.

Luther was an absolute gem. Great athlete, greater man. He made the most of the opportunities that came his way.

Thanks Steve. What a tremendous read.

Your are more than welcome, Doug! Thanks for visiting.