By David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman

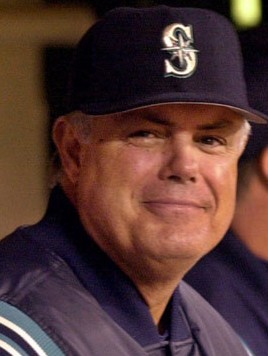

When Louis Victor Piniella became manager of the Mariners Nov. 9, 1992, he joined a franchise burdened with more losing seasons from inception (14) than any in any league in modern American pro sports history. So dire were circumstances in Seattle that the Mariners might have evacuated had not Pinella, who did so reluctantly, taken on the task of plugging and reversing the drain swirl.

A man of lesser passion could not have succeeded, but Piniella’s was such that within two years of his hiring the franchise had morphed, almost audaciously, into one of the most successful baseball markets in the country. Piniella produced a stream of winning teams, they drew record crowds, and all of it translated into bloated television ratings, making the Mariners during his tenure an economic peer to the New York Yankees and Dallas Cowboys.

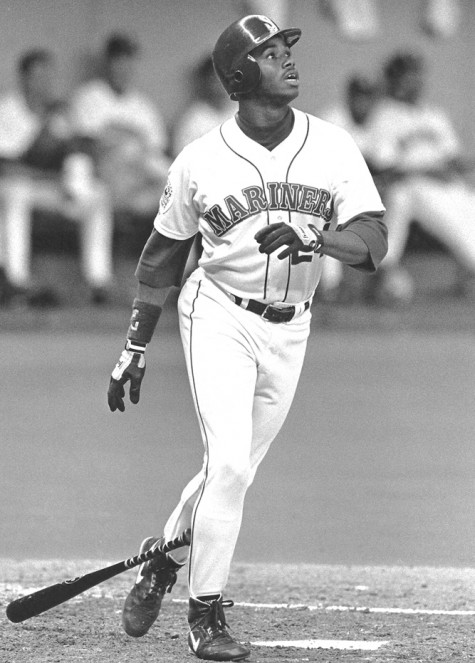

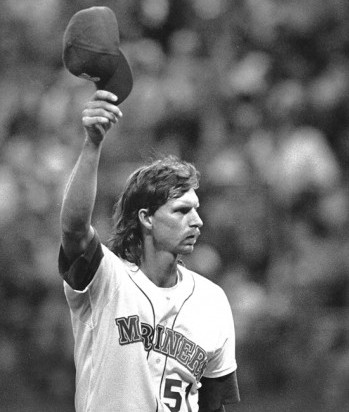

On the regional level, the Mariners rose to far more than a series of impressive bottom lines published annually by Forbes. They were a daily storyline and nightly drama that enthralled audiences. The Mariners employed a wonderful cast for the play – Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez, Edgar Martinez, Randy Johnson, Jay Buhner, et al – but most of all they featured the perfect puppeteer in Piniella, who accomplished something otherwise unheard of franchise history: he kept the customers wanting more, the cardinal rule of entertainment.

When, following the 2002 season, Piniella announced it was time to return to his roots in Tampa, FL., his decision provoked little anger or resentment, instead stirring great anguish. Seattle had never witnessed anything quite like Sweet Lou, and the suspicion was that his likes would not be seen again.

Unfortunately, that turned out to be the case. Since Piniella made his exit with 840 victories, seven winning seasons and four playoff appearances in 10 years, eight men, from Bob Melvin through Lloyd McClendon, have tried to rekindle the torch he lit. But in 12 seasons without Piniella, the eight have combined for three winning seasons, seven last-place finishes, no playoff appearances, and 1.5 million fewer fans annually in the seats.

Given the lapse of time, the erosion of the fan base is now largely taken for granted. But it underscores precisely the impact Piniella had on the franchise and why, on Saturday, he will become the eighth and perhaps most significant individual enshrined in the Mariners Hall of Fame. Piniella’s time here, spanning Refuse To Lose through Sodo Mojo, plainly went way too fast, the downside of all golden ages.

One of our first live looks at Piniella came in 1979 when he visited the Kingdome as the Yankees’ left fielder. A mid-inning incident on a Sunday afternoon should have alerted us to how competitive Piniella was, but at the time it was easy to write it off as a momentary hilarity, one quickly forgotten.

Ted Giannoulas, garbed as the San Diego Chicken, began his promotional act by waddling up the left-field line toward the Seattle bullpen, where he issued a series of taunting “clucks” in Piniella’s direction. The Chicken then crossed the foul line and approached Piniella, preparing for the bottom of the inning. In a scene reminiscent of stupid human tricks on “Animal Planet,” The Chicken got too close.

Finding no humor in the cartoonish entertainer, Piniella lurched forward and kicked and kicked at him, but couldn’t connect, The Chicken showing impressive quickness. Then Piniella did an astonishing thing: he charged The Chicken, all the while kicking the air with his right leg. Now understanding Piniella’s intent to maim, The Chicken made like Usain Bolt for the Yankees dugout and darned if Piniella didn’t chase him into it, still booting madly.

We should have known Piniella would respond that way, but we didn’t understand – yet — how seriously Piniella took the game. A subsequent reading of an essay on the Portland Beavers of the mid-1960s confirmed it.

During his minor league years in Portland – Piniella was in his early 20s – he was known as much for knocking over water coolers as he was for hitting baseballs. Piniella also sent bats, helmets and sundry other dugout items flying onto the field more than once.

Portland manager John Lipon finally installed a punching bag at one end of the dugout so Piniella could relieve his myriad frustrations, and management of the ritzy Multnomah Club often telephoned the Beavers office to complain about Piniella’s salty language during games at adjacent Multnomah Stadium.

Once, after hitting into a double play to end an inning, Piniella became so irate at himself that, as he assumed his defensive position, he couldn’t stand it anymore. So he ran up to the eight-foot, outfield fence and began kicking it. He kicked and kicked and kicked some more, and suddenly the fence began to wobble.

“As I started to walk away,” Piniella recalled later, “the damn thing fell on me.”

Pinning Piniella underneath it.

Piniella thrashed wildly about, trying to extricate himself, but it was useless. Beavers management ultimately had to send the grounds crew out to hoist the fence off Piniella, flattened underneath it.

That foreshadowed Piniella’s Roman candle of a career as a major league player and manager. Far as we know, Piniella remains the only big league skipper ever sued by an umpire.

In 1991, after Gary Darling made a call injurious to Piniella’s Cincinnati Reds, Piniella accused Darling of bias against his team. The Major League Umpires Association responded with a $5 million defamation lawsuit. Although the suit went nowhere, it played a part in Piniella’s decision to leave Cincinnati.

Piniella asked the Reds to pay for his legal defense, but the team offered neither help nor public support.

“They have liability insurance and lawyers working for them, but I get, ‘Well, our insurance rates will go up,'” Piniella complained. “What the hell do they have insurance for?”

So, at the begging of GM Woody Woodward, Sweet Lou came to Seattle. He didn’t really want to come – for the entire Piniella story and how the Mariners made baseball fly in Seattle, we recommend Art Thiel’s great book “Out Of Left Field” (Sasquatch Books, 2003) – but he needed the money. And the Mariners needed him more.

From 1977 through 1991 they churned through 10 managers, eking out only one winning season (83-79, 1991). What fans there were rattled around the Kingdome like BBs in a box car. One of the owners, a future Los Angeles-area slumlord named George Argyros, consistently sold off promising players in order to avoid paying them their due, and once even tried — in 1987 – to buy the San Diego Padres while he still owned the Mariners. Major League Baseball docked him 10 grand and banned him from day-to-day operations.

Between that episode and 1992, Seattle nearly lost the franchise several times and, as late as September, 1995, banana peels still were strewn upon the stairs. Then the unthinkable happened: a harmonic convergence of wildly improbable comebacks by the Mariners, coupled with a mega-collapse by the Angels, so stunning that the events transformed Seattle into a big-time baseball town practically overnight.

On Aug. 2, the Mariners trailed the Angels by 13 games in the AL West and Piniella said, ‘I don’t think we’re going to catch them.” As late as Aug. 20, the Mariners were still 12.5 games in arrears. But on Aug. 24, only recently returned from the disabled list, Griffey cracked a two-run, walk-off homer off John Wetteland, giving Seattle a 9-7 victory over Texas that launched the damndest comeback since the 1914 Miracle Braves.

We know what happened next, but certain details still astonish. The Mariners had 12 comeback wins after Sept. 2, including six in the final at-bat. Prior to taking over the AL West lead for good in late September, the Mariners spent a total of 68 days in first place from 1977-94, 36 in April.

From May 1, Seattle was in first place for two days in 1987, four days in 1991 and five days in 1994 – 11 days in 18 years. They matched that from Sept. 21 through Sept. 30, 1995.

The Mariners had 25 home crowds in excess of 50,000 in their first 18 years and five months of existence. Then they had four crowds in excess of 50,000 in six days between Sept. 22 and Oct. 2.

The fervor culminated in the club’s first playoff appearance, and a wild-card series win that concluded with Edgar Martinez’s double against the Yankees Oct. 8. Griffey slid into the happiest home-plate pileup in Seattle baseball history. “The hit, the run, the play, the game, and the series that saved baseball in Seattle,” as Piniella later described it, transformed the franchise. Instead of fleeing an outdated Kingdome for Florida, the Mariners received a new ballpark and, for the remainder of Piniella’s tenure, a virtual license to print money.

In Piniella’s final season, 2002, the Mariners drew a record 3.5 million, and a comment by Edgar Martinez when Piniella departed still resonates.

“I’ve been here since early on. A lot of people think it was the players that changed baseball in Seattle,” said Martinez. “To me, all the credit goes to Lou. He’s the one who changed everything in Seattle. I saw it first in spring training in 1993. Everything was different. I’m going to miss him, and I think the organization and city will miss him.”

They have. Pinella was not only an astute manager but a once-in-a-lifetime character, the man who orchestrated center stage for most of the memorable moments in franchise history, many of his own making.

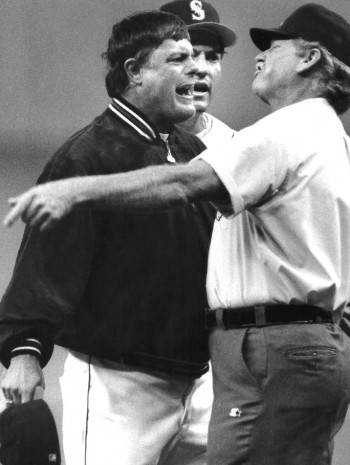

While Piniella rewrote the big picture in Seattle, principally by changing the culture and competitive character of his ball clubs, the little pictures remain equally vivid, particularly the tantrums when he felt baseball justice had turned a blind eye. There were many, starting with his participation in a 20-minute to-do June 16, 1993, when Piniella and seven players were tossed in Baltimore.

More representative was Piniella’s outburst May 17, 1994, when 16 futile kicks and four scoops of dirt on home plate earned him his first Kingdome ouster. But even more colorful were theatrical tirades in Cleveland and at Safeco Field, neither of which took place during a 10-game span in September of 1996 when Piniella was pitched three times, a boggling spree.

Piniella’s purple-faced paroxysm in Cleveland occurred Aug. 26,1998. Late in what became a 5-3 Seattle loss, Piniella rushed from the dugout to protest when umpire Larry Barnett called out third baseman Russ Davis for running outside the basepath. After an obligatory debate, Piniella returned to the dugout. Then, to his amazement, Piniella found out he’d been ejected.

Out he came again, throwing his cap on the ground, whiffing with every kick. On his way back to the dugout, Piniella kicked his hat five more times. After the third, Mariners broadcaster Dave Niehaus cried, “He got some distance on that one! That was a three-pointer right there!”

Piniella tossed his cap into the stands, but a quick-witted Cleveland fan tossed it back as cameras panned the Seattle dugout, showing that players could barely keep from laughing aloud.

Even Cleveland manager Mike Hargrove, one of the eight to ultimately succeed Piniella and no candidate for inclusion in Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, expressed awe by the scale of Piniella’s antics.

“I just don’t know how anybody can think of that many things to yell,” said Hargrove, amazed.

“I don’t blame anyone for laughing,” said Piniella. “Everyone likes to see someone make a fool of themselves in front of 40,000 people.”

Two days later, Piniella told reporters, “You know the andro stuff (androstenedione, a performance-enhancer) everyone’s talking about for muscles? If I was on that, I’d have kicked my hat out of the stadium.”

Two weeks before he managed his final game for Seattle, Sept. 18, 2002, Piniella orchestrated his most memorable Safeco Field nut-out. It lasted two minutes and six seconds, surely a record for a Seattle manager. It began after a close call at first base that was exacerbated when Piniella determined that umpire C.B. Bucknor had not only missed the call but “smirked” after making it.

After two hat kicks and two throw-downs, a solid boot sent Piniella’s chapeau 10 feet. To first base coach Johnny Moses, Piniella yelled (plain to lip-readers everywhere): “Get my @#!$%! hat!” Moses obliged, whereupon Pinella applied his foot to it again. That was followed by an uprooting of first base, which ended up in foul territory down the left-field line. When Piniella retrieved the base, he threw it again and stomped off the field, thumbed by Bucknor, to enthusiastic chants of “Lou! Lou!”

“The ump had the nerve to have a smirk on his face,” Piniella explained.

After the game, Piniella conceded, “My hamstring hurts and my shoulder is sore.”

Said bench coach John McLaren, witness to a majority of Piniella career tirades: “That one was the best. Lou had all his greatest hits in it.”

A few days later, a reporter showed Piniella a photograph of him kicking his hat.

“I’m going to send the picture to John Gruden (then coach of the NFL Tampa Bay Buccaneers),” Piniella said. “I’m ready for the season. That’s good form there.”

While Piniella managed the best teams in Mariners history, a collection that included at least three certain Hall of Famers in Griffey, Johnson and Ichiro, his tenure was not without headaches. For all the home runs his players hit, he suffered through years of inconsistency by his pitchers, who generally drove Piniella crazy, especially the young ones. But not always.

Game stories tell us that on June 21, 1995, Piniella almost had a stroke when his veteran starting pitcher, Chris Bosio, issued six four-pitch, unintentional walks at Chicago. Three weeks earlier, on June 6, against Baltimore, one of his starters, Dave Fleming, threw a curveball on a pitchout, sending Piniella into an industrial-grade dither.

“Damn, I thought I’d seen everything in baseball,” Piniella said. “You see a lot of strange things in this game, but I’ve never seen anyone throw a curveball on a pitchout. To throw the runner out after that is like asking Shaquille O’Neal to dunk from his knees.’’

Piniella also saw Bobby Ayala blow a franchise-record 30 saves (Tom Wilhelmsen is the active leader with 12) that helped derail playoff runs.

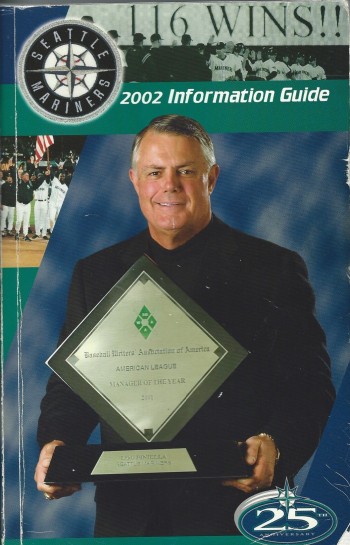

Piniella had by far his best team in 2001, when the Mariners won 116 games, setting an American League single-season record. That surprised even Piniella, a demanding perfectionist.

“When we got to 20 games over .500, I thought to myself: ‘What is going on?’ Then we got to 30 games, then we got to 40, then 50 and I said, ‘My God, when is this going to end?’ I still don’t know how we did that.”

Former catcher Dan Wilson told a story for the Great Book of Seattle Sports Lists in 2009 about that season that shed an entirely different light on Piniella.

“A more serious moment from Lou came in 2001 when baseball resumed after 9/11,” Wilson said. “Before the game when we would clinch the division at Safeco, Lou called me and a couple of others into his office to discuss what he thought should happen after the game if we won. He wanted to handle this in an appropriate, considerate fashion.

“He thought that we had accomplished something outstanding (eventually, 116 wins), but the people of New York were really on his mind. With seriousness and compassion that I had not witnessed from him to this degree, he drew up plans for how we were to proceed if we won. He was the architect of what is, in my mind, one of the classiest and most inspirational moments in baseball history.

“I’m sure you remember the moment of silence and then a carrying of the American flag around the infield. Fans, players, coaches were all crying. The moment was so captivating. Lou was the hero of that night.”

Sweet Lou, who more than anything made baseball fun, was the hero of hundreds of Mariner nights. Saturday will be another, when he enters the Mariners Hall of Fame. Too bad he can’t be cloned.

Mariners Hall of Famers

| Year | Date | Player | Pos. | Skinny |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | June 14 | Alvin Davis | 1B | 160 home runs, 1984 Rookie of Year |

| 2000 | May 7 | Dave Niehaus | Media | Beloved voice of club since inception |

| 2004 | Aug. 24 | Jay Buhner | OF | 307 home runs, Gold Glover in right |

| 2006 | June 2 | Edgar Martinez | DH | Delivered biggest hit in team history |

| 2012 | July 28 | Randy Johnson | LHP | Big Unit won 130 games, ’95 Cy Young |

| 2012 | July 28 | Dan Wilson | C | Played 12 years, played in 1,251 games |

| 2013 | Aug. 10 | Ken Griffey Jr. | OF | 417 homers for Mariners, 10 Gold Gloves |

| 2014 | Aug. 9 | Lou Piniella | Mgr. | Led club to four postseason appearances |

——————————————

Many of the historic images published on Sportspress Northwest are provided by resident Northwest sports history aficionado David Eskenazi. Check out David’s Wayback Machine Archive. David can be reached at (206) 441-1900, or at seattlesportshistory@gmail.com

26 Comments

It’s been disappointing that the culture that Lou established quickly left with his departure. Despite hiring managers with established pedigrees the club hasn’t matched what Lou was able to do. Heck, since his firing Bob Melvin has been Manager of the Year in two different leagues and been to the playoffs in both as well.

Going to be great to see Lou again. Hope he can do some broadcasts with the club in the future.

Lou in the booth: “We need another bat!”

No kidding! But seriously, what I liked about Lou is that he’s a great storyteller. Especially when you’d listen to him on the radio pre game broadcasts. He’s seen a lot of baseball and has a great way of telling you about it.

That’s exactly why Lou finally gave up and left! Remember? He kept begging Big Town Car and Chuckie Cheesehead for a serious right-handed hitter and they refused to get someone. Twelve years later and we STILL don’t have one!

The reason Lou pulled the old “I want to be closer to my family” canard out of his oft-kicked hat is because he got sick of dealing with Lincoln and Armstrong. They can take personal credit for the end of the Golden Era and the inception of the Era of Futility.

One clown down, one and a franchise sale to go.

Lou wasn’t making stuff up about needing to be closer to his kids. But as you read in “Out of Left Field,” he and Lincoln had a falling out. Lou also has enough self-awareness that he knows he wears people out. To this day, he can’t figure how he lasted 10 years in the same job.

He may have worn his employers down, but the players (excluding the pitchers of course) and the fans loved him. :-)

followed IMMEDIATELY by a call into the Lincolnland head office to be dressed-down as “insubordinate” by baseball’s most inept and egoistic CEO ( and that’s among very tough competition)– after which Lou needs to go home to spend more time with his family and Lincoln claims to be on the hot seat and remains inept and inauthentic in all he does and says in the realm of baseball…

How many of you aware that Lou Pinella started his majpr league career as a Seattle Pilot?

My hand is raised.

Actually Baseball Almanac shows 1 AB with the Orioles in 1964 and 5 ABs with the Indians in ’68. He was at spring training with the Pilots in ’69 but traded to the Royals before the season started.

Who made the trade, Woody Woodward or Bill Bavasi? :)

Dick Balderson, wasn’t it?

Hal Keller?

That is correct. One has to either be a very good researcher, or just old. I’m the latter.

Mine too. Thanks for the card image, RadioGuy! In my trusty Seattle Pilots Official Scorebook (35¢ don’t ya know) Lou was listed as coming from Cleveland in the third round of the expansion draft.

My baseball card collection has diminished over the years, but I still have all three Lou Piniella rookie cards (1964, 1968, 1969) with three different teams. I think he might hold the record for most appearances on a rookie card, although it seems Keith Lampard was always showing up on one.

Here’s a link to a card that was never issued but brings good memories with it: http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-ImY63p_xNic/Tzr9w05nphI/AAAAAAAAB_I/XXnt8t8cJEA/s1600/1969+Topps+Lou+Piniella.jpg

The Mariner’s first draft choice was Ruppert Jones. While he was only a Mariner for three years, he was the soul of a pathetic group. Who can forget the fans chanting, “Rupe, Rupe” every plate appearance. Why isn’t he in the mariner’s hall of fame?

I think it’s probably because he only played three years in Seattle (and his plate performance in 1978 was nothing to write home about). I was a “Ruppert Roota” (apologies to Philip Roth) from the GA seats in left and remember that he WAS the M’s first All-Star, but his numbers here just don’t add up.

I think a better case might be made for Julio Cruz, who played here seven years and still lives in the area. Juuuuuuulioooooo was an exciting player throughout. Not much of a batter, although his OBP in Seattle of .321 was decent enough, but a very good, acrobatic second baseman and arguably the best base-stealer the M’s have ever had (Ichiro had more SBs, but he also had far more PAs).

Today’s teenagers will be amazed that in Piniella’s day, the Mariners held it all over the Seahawks for the city’s love. When the Hawks were relentlessly mediocre during the ’90s and early aughts, Piniella led the M’s to one of the better non-Yankees runs in the American League, and turned Seattle on to baseball. When most teams only hope to have head-turning seasons like 1995 or 2001 once in a generation, the Mariners had it two in seven. No wonder Mike Cameron even called Safeco Field games “the biggest block party around”, and even the Kingdome was a fun ballpark during the team’s last few years there.

By achievement and personalities, the mid-90s Mariners were a compelling group. And there’s nothing in sports like the daily-ness of a pennant race.

Mariners HOF? Lou belongs in Cooperstown. When one considers this franchise has seen the playoffs only 4 times in 37 seasons, all 4 led by Lou, his qualifications as a historically great major league manager become self evident.

A fine argument. And when he was done, he was traded for a starting LF.

Outside Seattle, he also won a World Series with the Reds right after the Pete Rose mess, led the Cubs (!) to consecutive division titles, and cleared .500 with the blah mid-’80s Yankees. Only the bad Tampa team he inherited is keeping him, I think, from being an automatic HOFer as a manager.

In all seriousness, I think the Reds championship gives him serious HOF cred. They swept the Mighty As for gosh sakes. The problem is the eastern baseball writers won’t see his time in southern Alaska for the great managing job it was. Through shear force of will he turned the Ms into consistent winners for the only time in their history.

Thanks for the memories. The rise of the franchise during the 90’s was thrilling to watch. I was a Mariner season ticket holder in 1989 when Ken Griffey Jr. started the season in center field and was immediately the best player of BOTH teams. I thought Niehaus was going to have a cardiac when Randy Johnson threw his no-hitter (they played his audio on the TV’s up on the two hundred level). Then a supposedly washed up pitcher named Chris Bosio threw another gem after walking the first two Red Sox batters he faced and Omar Visquel made an electrifying bare handed catch and throw to first to end it( I was at that one too!). Jay Buhner OWNED anyone who tried to make it home on anything that didn’t hit high on the wall or go over in right field. Everyone forgets what a defensive force he was. I could go on, but it only makes me feel like a sad old baseball fan. :-)